Hannah Gadsby and the Problem With Picasso

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Pull your f–king socks up,” comedian Hannah Gadsby rages in their groundbreaking stand-up special “Nannette.” They are speaking to the famous men, including most pointedly Pablo Picasso, the towering “genius” of the modern art canon and the father (with Georges Braque) of Cubism.

And by “socks,” Gadsby means stop exorcising your demons on people who are less powerful just because society let you get away with it for centuries.

More from WWD

Swatch x Jean-Michel Basquiat Collection Reimagines Iconic Motifs

A Look Inside Alessandro Maria Ferreri's Gorgeous Rome Apartment

Gadsby’s extended soliloquy on Picasso came at the outset of #MeToo; they performed the show at the Sydney Opera House in 2017; it was released as a Netflix special in the spring of 2018, several months into a movement that had forced a reexamination of gendered power dynamics and the silence that served to perpetuated abuse and subjugation. The special served as a shockwave of clarity, piercing the reductive narrative that admonishes us to “separate the art from the artist.”

Now Gadsby is collaborating with the Brooklyn Museum on its show “It’s Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” which opens June 2 and runs through Sept. 24. It’s Gadsby’s first go-round as a curator. Anne Pasternak, the museum’s director, reached out to Gadsby shortly after “Nanette” dropped and the comedian had an informal conversation with the museum’s curators. It was, says Catherine Morris, senior curator of the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, just a “fan girl” moment.

“We talked about, wouldn’t it be cool if someday…”

When the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death in 1973 came upon the horizon, someday became a reality.

Underpinning the exhibition is Picasso’s “The Vollard Suite,” a series of etchings completed in 1937 and commissioned by prominent French art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who gave Picasso his first major exhibit in 1901. Done in the neoclassical style, “The Vollard Suite” is a phantasmagoria of violence and carnal desire and has long been interpreted as an exploration of Picasso’s disregard and abuse of women, particularly Marie-Thérèse Walter, who was 17 years old when Picasso, then 45 and married, made her his model, muse and sexual partner.

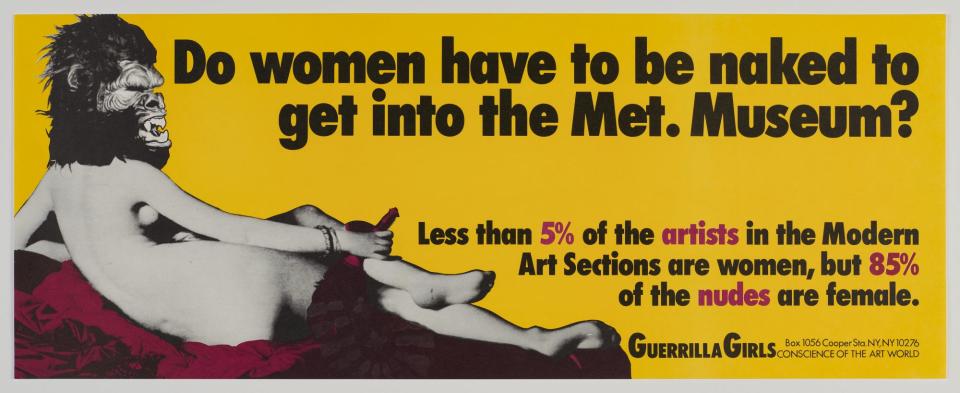

Vollard — who also championed the work of Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir — is a key figure in the myth-making surrounding Picasso. And Gadsby was insistent that this work, and its themes, be central to the exhibition, which juxtaposes Picasso’s work with that of 20th and 21st century female artists including Cecily Brown, Renee Cox, Käthe Kollwitz, Dindga McCannon, Ana Mendieta, Marilyn Minter, Joan Semmel, Kiki Smith, May Stevens, Mickalene Thomas and the Guerrilla Girls, the activist group of anonymous female artists formed in 1985.

![Minotaure caressant du mufle la main d'une dormeuse [The Minotaur caressing with its muzzle the hand of a sleeping woman]. 2nd state (Suite Vollard 93). Boisgeloup, June 18, 1933. Drypoint, 29.9 x 36.5 cm. MP1982-152. Photo: Mathieu Rabeau.](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/ECyVZobo1UbnOqJYzLyAdw--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTc3Ng--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/wwd_409/d41ae2e17f6946a98b1d961e28f6523f)

Organized in collaboration with Musée National Picasso in Paris, it is among a flurry of exhibitions marking the anniversary of Picasso’s death in April 1973, just a few months after Roe v. Wade was decided, and at the outset of second-wave feminism and the beginning of what we now think of as feminist art history.

“Picasso and this conversation in relationship to problematic figures is really a conversation about the history of the modern art period, and the figures who came out of it, lessons it taught us, the things we are now changing and reexamining,” Morris says.

“And so anybody who comes to the exhibition is not going to see a one-to-one conversation of somebody responding to Picasso. It is a much more nuanced and elastic installation in which you see a lot of incredible work by women artists responding to the canon. And in many cases there are things they love about the canon. And that’s why we’re having this conversation. If we wanted to cancel Picasso, we wouldn’t be doing this.”

Indeed, Picasso’s influence on modern art is hard to understate. As Gadsby has acknowledged in “Nanette,” Cubism was a seismic development in not just art but our understanding of the potential of art to obliterate accepted norms and elevate new — and different — perspectives.

As Gadsby put it in “Nanette”: “I believe Picasso was right. I believe we could paint a better world if we learned how to see it from all perspectives, as many perspectives as we possibly could. Because diversity is a strength. Difference is a teacher. Fear difference, you learn nothing.”

At the same time, Picasso’s misogyny has been well-documented, not only through his art, but in books, movies and popular culture. But if the culture at large has been engaged in a broad — and messy — conversation about the lionization of men of Picasso’s ilk, cultural institutions have been hesitant to directly participate in the debate, let alone lead it. The exhibition is an attempt to have that conversation with nuance and without preconceived conclusions, says Lisa Small, senior curator of the Brooklyn Museum’s European Art, who co-curated the show.

“These are conversations and issues that are becoming very present in people’s minds,” Small says. “But we can’t underestimate how few conversations that have even touched upon this have happened in the museum space. We are not claiming — news flash! — Picasso was a misogynist. As an institution representative of the types of institutions that have historically completely shied away from having this type of conversation, we are having it. We are putting it out there, and not in a way that is meant to destroy Picasso’s reputation or make a claim of him not being viable anymore. As an institution where people come to not only see art, but think about what it means in its past moment and its present moment and its future moment, we want to embrace that conversation in a much more forthright way.”

Of course, it is not simply that cultural intuitions have eschewed frank explorations of inequality in the art history canon and in their own choices about what hangs on their walls. They have also been complicit in the reputation laundering of the rich and powerful who for years have benefited from these systems.

As the Sackler Curator at the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Morris is acutely aware of these sin-of-association assumptions. (Elizabeth A. Sackler is the daughter of Arthur Sackler, who in 1952 purchased the pharmaceutical company that would become Purdue Pharma. When he died in 1987, his stake in the company was sold to his brothers Mortimer and Raymond Sackler; Purdue Pharma released oxycontin in 1996. Elizabeth Sackler has disavowed her uncles, come out in support of artist Nan Goldin’s campaign against the company and stressed that she has not benefited financially from Purdue’s oxycontin scourge.)

Purdue Pharma has faced an avalanche of lawsuits and in 2019 agreed to pay $6 billion to resolve the claims; the company was dissolved in 2021. At this point, more than 20 universities and cultural institutions have stripped the Sackler name from their buildings, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City and the National Gallery and the British Museum in London.

The Brooklyn Museum remains an outlier. And Elizabeth A. Sackler’s continued association with the museum was the topic of conversations during the planning of the exhibition. More recently, Gadsby has said that they remained conflicted about the role of “cultural institutions” as receptacles for “problematic people [to] funnel their money” in exchange for inclusion on boards and their names etched in marble. It is an issue with which the museum continues to grapple.

“Taking the position of nuance in this discussion is not an easy position to take because, as all things that are monolithic in our soundbite and social media culture — including, I hate Picasso, if you want to go there — it doesn’t really reflect lived reality,” Morris says. “Elizabeth A. Sackler is not a monolithic member of a monolithic family that monolithically got together and did this horrible thing. And they did a horrible thing! Nan Goldin et all, and the research, and the groundswell of public opinion around that is clear. And in the midst of that we have tried to maintain our position.

“Anytime I do anything, from public speaking to interviewing an intern to talking to Hannah Gadsby, I say, ‘This is our position, are you comfortable with this? And I’m happy to answer any questions,’” Morris continues. “The other thing that the #MeToo movement, and our lives in the last few years, has taught us is the best thing we can be is transparent.”

Best of WWD