Hanif Abdurraqib Knows What Makes Basketball Great

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

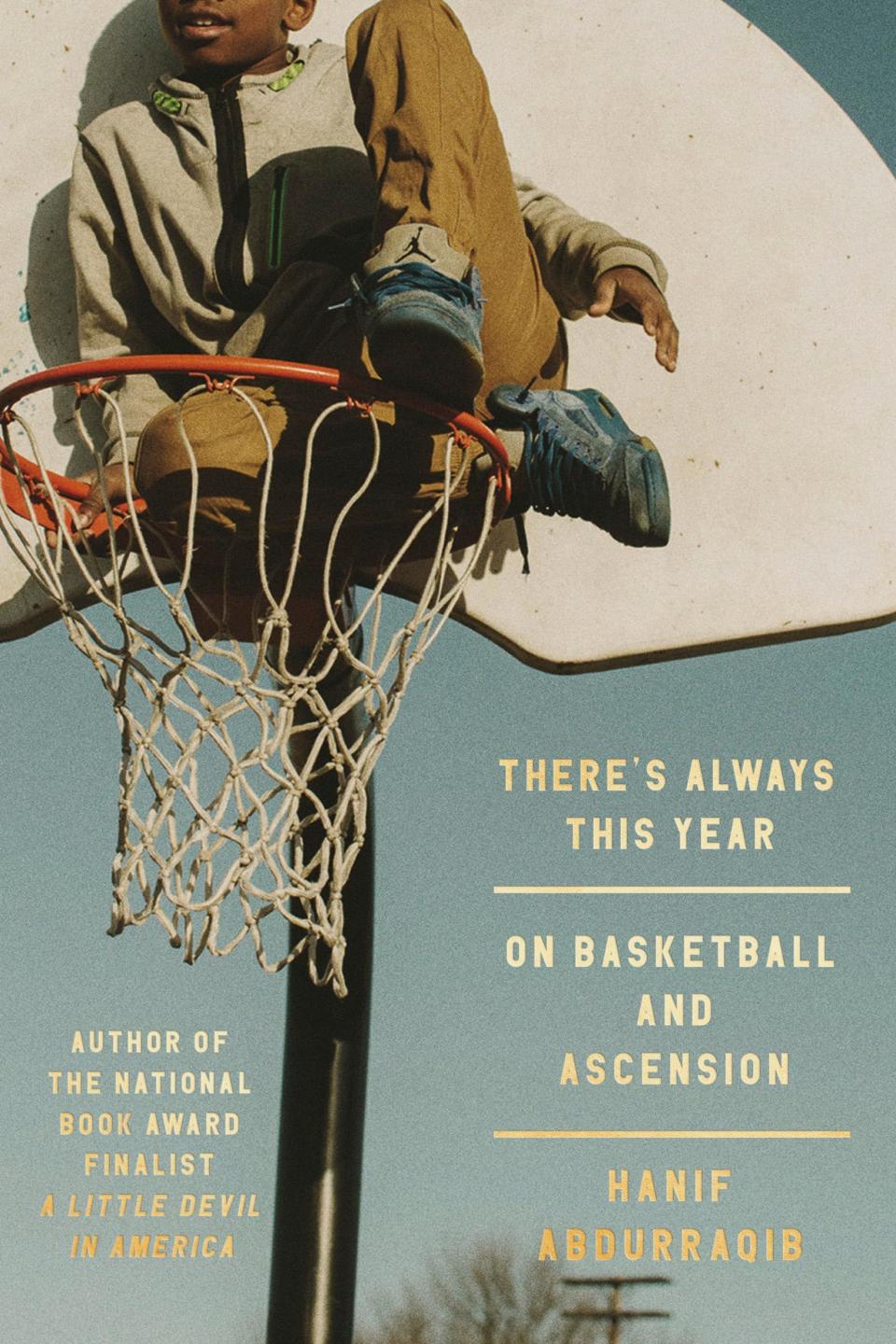

For a sport so full of stories, basketball is scarcely represented in literature, or at least literature for adults. When we do get a basketball book, it’s usually full of statistics or reportage. Acclaimed author Hanif Abdurraqib’s latest, There’s Always This Year (a joke basketball fans will get), is more about relationships: a fan’s relationship to a player or a team; a player’s relationship to a city; a son’s relationship to his father; our human relationship to our own mortality.

There’s Always This Year follows two people, primarily—Hanif Abdurraqib and LeBron James—in and outside of the place(s) they call home. Abdurraqib, a Columbus native who grew up playing not far from LeBron, is the perfect person to write about the King, and he brings to this book his usual mix of insight, humor, beauty, and joy. There’s Always This Year comes on the heels of the National Book Award finalist A Little Devil in America and the New York Times bestseller Go Ahead in the Rain.

It isn’t your usual basketball story. “I can tell you about guys who didn’t hoop to get away from the streets, or to get out of anywhere,” Abdurraqib writes. “Guys who hooped because they wanted to be respected on the streets they loved. They wanted to make themselves infamous in the place that held them, and that, too, is a type of making it. People just looking for a place to feel invincible, for a few hours, in a city that might otherwise swallow them whole.”

Abdurraqib was one of these hoopers. In the book, a brief stint outside of Ohio finds him homesick for the city where he grew up and almost died, which he describes in our interview. He returns for an NBA Finals game to watch LeBron in his second go-around with the Cleveland Cavaliers. This is a book about return, and about the kind of grace and resignation a return entails.

During the height of LeBron’s first run in Cleveland, you could find the word “witness” all over the city. “We are all witnesses,” read the largest and most famous mural of the King. When he left, the mural was dismantled. The witnesses, however, including Abdurraqib, remained. There’s Always This Year is a great work of witnessing from one of America’s most remarkable writers.

Abdurraqib spoke with Esquire by Zoom. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: Where did you come up with the idea of counting down time in the chapters like in an NBA game?

HANIF ABDURRAQIB: Initially that was only going to be for the pre-game section. I dreamed this up in the pre-game section as a way to play with this idea of descent—to speak of baldness, or the overarching idea of baldness, as: you begin with something and then slowly that something diminishes and then there is nothing.

I had dreamed of this book since 2018, and one of the first things I thought was something beginning abundant and then diminishing slowly and then having a literal clock to represent that and to kind of act as a container for that idea, the enacting of that idea. But then, when I got done with the pre-game, I thought two things. One was: it's going to be kind of ridiculous if that just goes away and never comes back, you know? The other thing was there was a way the entire book was starting to congeal around these ideas of descent. And I know that “ascension” is in the subtitle, but really that's in some ways a trick.

There's Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension

amazon.com

$26.23

The book contains sections about famous Ohio aviators. What was your intention there?

I'm excited that people are asking about that. Those were the first things I wrote, and the way I tasked myself with writing them was, Let's begin with literal aviators, then see how effectively I can maneuver away from the strictness of the literal to present something a bit more emotional or ephemeral. To have these guide posts, these little miniature poems, was good for me because it was important for me to say, You're actually not beholden. You did not dream this book to be an in-depth explanation of the 2016 NBA finals.

What was the dream for this book?

I was obsessing over Lebron James and mortality. We're around the same age. We grew up playing basketball in Ohio around the same time. I saw this video of him in early 2020, in the beginning of lockdown, where his beard was grayer than I had ever seen it before. It was around the time we began to talk about LeBron James as an immortal figure. That's when something turned for me.

[In There’s Always This Year] I think I'm considering if immortality is something anyone should desire. I am someone who very plainly and clearly did not want to live beyond the age of 25. I thought back then that I was not afraid of death. I thought, This world is not serving me. So many people I love have chosen to exit the world or have exited the world beyond their choice. And now, 15 years later, when you survive that kind of impulse, in my case, there's gratitude, but there's also immense confusion that, for me, is highlighted by the fact that I am maybe more afraid of dying now than I was when I did not want to be alive. I'm sometimes on this quest for forgiveness for my past selves, maybe. I think if that happens, then my present existence will begin to make a little more sense to me.

Have you noticed a shift from following teams to following players? Maybe it started with LeBron’s decision, or with the rise of fantasy sports?

It does feel like there's a generation of guys, including some of the young writers I work with, who don't follow teams; they just follow guys. To affix oneself to a team that’s completely beyond your control is a bit more romantic. It’s like giving your heart over. I have been a Timberwolves fan now for three decades. Every year, I surrender myself to it. That, to me, is maybe braver. It's all about surrender, you know?

You think there's a level of fandom that courts suffering, though?

If you’ve seen enough unique horrors befall the teams you love, then you just kind of prepare yourself for this inevitable doom. I think that actually makes the exuberance that exists, when the doom doesn't befall, way more thrilling. I gravitate towards this doomsday approach to fandom. Because it means that when it's your moment, it will feel like nothing you've ever felt before. It perhaps allows you to appreciate the rarity of that moment being yours. I don't really trust fans who expect to win, even if that expectation is hard-earned and justified.

You play the role of the pessimist in your book, too. Is it a kind of protection?

It's hard to tell. I think I'm a romantic. I'm also a cynic. I don't necessarily think those two things are at odds. If I went outside right now and looked in the sky, and saw a UFO slowly descending, I would say, “That's probably bad, but it's not here yet. And so, what can I do?” I have literal playlists, no joke, that I call my “apocalypse romance” playlists, of maybe 5 to 7 songs wherein if I could see the end of the world coming, depending on the time of day, mood, whatever, here are the last things I'd want to hear. Here are the last things that would drive me to maybe call a person or to text a person, or something that reminds me of my mother one last time, in case she's not waiting for me on the other side of this life.

People may see that as pessimistic in some ways. But to me, it's because the only thing I know is that we are required to die. It's a requirement of us, perhaps the only requirement we've got, and I don't think it's pessimistic to make peace with that and ask myself what I’m going to do with what I know about the requirements that are waiting for me no matter what.

You're talking about a kind of difference between honesty and the deceptions we often live under in order to make ourselves okay with a pretty brutal world.

Yeah, and sometimes the deceptions we live with and tell ourselves just to get through a quotidian day. There are ways that people lie to themselves in order to avoid reckoning with their complicities in a world that is, in many ways, eating people alive. But some of the lies we tell ourselves are just not that high stakes. I'm trying to really ask the individual what they believe their responsibility is in a system that is almost built to swallow them alive, and sometimes, it's orders of magnitude. The lies we tell ourselves are not always at the same magnitude. It's one thing to say, I am going to look away from any of the ongoing genocides in the world so that I don't have to think about them. It's another thing to say, I'm going set my alarm for 6:00 AM tomorrow, knowing in my heart that I will be up at midnight tonight scrolling through old YouTube clips of who knows what.

The book starts with enemies. What is the role of enemies here?

The thesis, for me, is that you know going into the book that in order for me, speaker, and you, reader, to decide on a collective enemy, then we have to decide at least in part that an enemy is someone who is interrupting our ability to love each other. An enemy is anyone placing a barrier between my affection for you or this team or this place. My enemies are the people who were deriding the Fab 5, and yes, my enemies were the people who took the rims off of the basketball hoops in 2020, even if I understood the scientific need for that, perhaps. That person was my enemy because they placed the barrier between me and my affection.

amazon.com

$14.99

There's a flexibility in who can weave in and out of that space and still have our love. Which is to say that my father, for example, can weave into the space of enemy but not stay there. To play with the term enemy in this way is also to explore the depth of grace that I have to offer others. Which is to say, you may be an enemy always—certainly there are enemies that are bronzed in amber for me—but there are also people I love who have woven into the space of enemy and then woven out. There are people whom I have loved and then invented into an enemy and they haven't earned that. That invention exists because I am hurting, because I am newly in pain or newly lonely, and to have an enemy is to have someone who is the object of focus. When someone or something is the object of focus, it can blur the line between enemy and beloved.

I really liked introducing the idea of enemy early on and then turning it as the book went on—to say, “Enemy in the traditional sense is not just the large and bad evil villain in your personal story.” It behooves us, I think, to consider our enemy as anyone close to us who betrays that closeness or betrays what they know about us. And even on accident, even by not knowing us as well as they think they did, or even by wanting to love us and just stumbling through wanting to love us, as wanting to love people can sometimes be a forest that is more trees than path.

You know, there's a way to say, “I have loved you and you have drifted into this space of enemy, but that does not mean I don't love you and that does not mean I won't love you again.” It's also the reality of “I love you and I miss you and you are not coming back and because you are not coming back, I have invented you into an enemy so that I might not love you as much as I once did.”

There is this thing that is real where, the longer someone has been dead to me in my life, the less I remember the things I didn't like about them. My friend Tyler, whom I miss every day, has been dead now for 18 years, and one of the last things that happened before he died was we had this really big fight. As the years have passed, that fight has become so blurred in my memory that now I genuinely can't even remember it, because all I remember are the moments of affection. To think about the enemy as a fluid target and a fluid entity served this book and also served me—to think a lot about grace and how to offer grace.

You Might Also Like