A Groundbreaking Exhibit About the American Cowboy Just Opened at This Colorado Museum

At Denver's Museum of Contemporary Art, the American cowboy gets his close up.

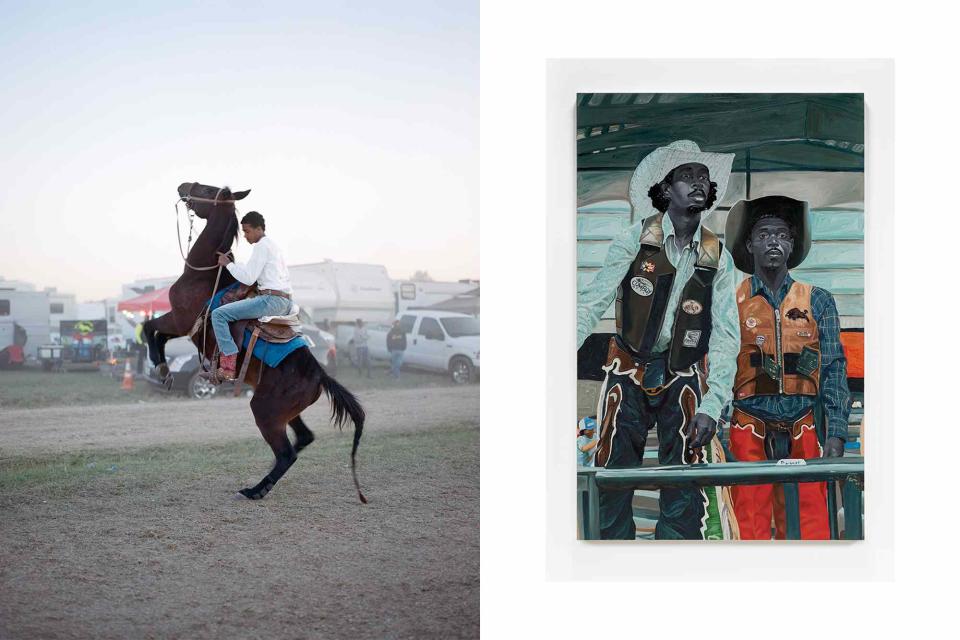

Akasha Rabut/Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Denver; OTIS KWAME QUAICOE/ALMINE RECH/HUGARD & VANOVERSCHELDE/COURTESY OF MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART DENVER

Trail Rider at Sunset, a photograph by Akasha Rabut; Rodeo Boys, an oil and fabric canvas by Otis Kwame Quaicoe.The marlboro man coolly raising a cigarette to his lips; John Wayne gazing at the horizon from the saddle; the Lone Ranger drawing his pistol: the cowboy may be one of America’s most enduring figures. But as a new exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver argues, the archetype of the strong, silent, solitary man — and one who was assumed to be straight and white — is only one part of the story.

From 1868 to 1895, roughly 35,000 men worked as cowboys, and, according to contemporary scholarship, an estimated 30 percent of them were Black or Mexican. In fact, the word cowboy was originally tied to the institution of slavery: after the Civil War, many cattle hands were formerly enslaved men or their sons.

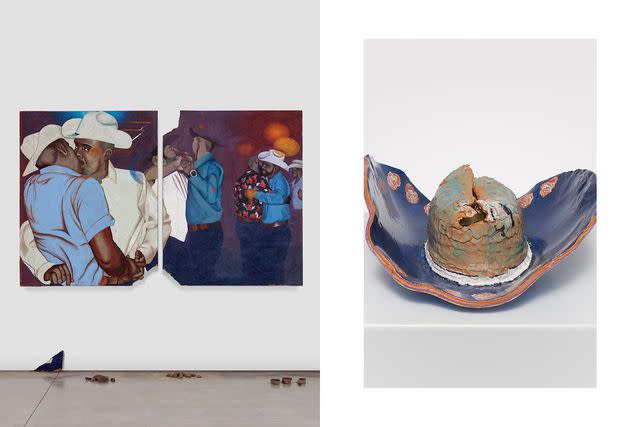

Otis Kwame Quaicoe/Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Denver; Stefan Simchowitz/Courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Denver

Rafa Esparza's painting, al Tempo after Sean Maung; Ken Taylor Reynaga’s sculpture Sombrero Ceramic Aqua.“Those tasked with protecting the cattle weren’t allowed to be referred to as ‘men,’ ” says Nora Burnett Abrams, the museum’s director and co-curator of the exhibit.

Cowboys were not macho adventurers, but laborers: the work was long, hard, and had low pay. That image began to change with turn-of-the-20th-century road shows like “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West,” which transformed the cowboy from a hired hand into a brash vigilante who swept into town to save the day. Dime novels furthered this trope, as did western movies of the mid 20th century.

Courtesy of Akasha Rabu and Museum of Contemporary Art Denver

Akasha Rabut's Untitled (ARAB 0024)The exhibit, “Cowboy,” which presents 70 works from 27 artists and is on view through February, examines this history and illuminates those who were written out of it, including Indigenous and queer men. The show challenges ideas about who and what a cowboy can be, with pieces like Rafa Esparza’s "Al Tempo," an acrylic diptych that shows cowboys of color dancing. Kenneth Tam’s film, "Silent Spikes," depicts Asian men in cowboy cosplay and alludes to Chinese workers who toiled in the railroad and agricultural industries in the 19th century.

Related: America's Best Dude Ranches

“The idea of ‘the West’ was a manufactured, mythical landscape, with the cowboy as someone who can tame it, bend it, and control it,” Burnett Abrams says. “We hope to build up a cowboy that is more multidimensional and complex.”

A version of this story first appeared in the November 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Go West, Young Man."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.