How To Grieve When You've Lost a Loved One

There’s no easy way to say goodbye to a loved one. But if you can rise to the challenge with openness, awareness, wit, and grace, you may discover that death can bring an often rich, sometimes strange, always profound new dimension to life.

From the October issue of O.

Tea and Sympathy

At death cafes, mortals cozy up to chat about the ultimate taboo.

Twice a month, Megan Mooney, a social worker in St. Joseph, Missouri, hosts a Zoom get-together where everyone’s invited to eat cake, drink tea, and discuss a subject that, in the usual hierarchy of appealing conversation topics, falls somewhere between bank balances and bunion surgery. “We talk about death,” says Mooney, who adds that our collective cultural denial of mortality has left many of us starved for conversation about it. “In Victorian times, we used to be surrounded by reminders of death. We held funerals and wakes at home. We wore black when we were in mourning. Now people tell me, ‘I’ve tried to talk to my family and friends about dying, and they call me morbid.’”

Mooney’s gatherings are part of a larger Death Cafe movement, founded in 2011 by Jon Underwood, a London Buddhist who believed that frank conversations about death could help us make the most of our finite lives.Inspired by the work of sociologist Bernard Crettaz, who hosted cafés mortels in France and his native Switzerland, Underwood organized the first Death Cafe in his basement, led by his mother, psychotherapist Susan Barsky Reid. “When we started, it was very structured,” says Reid. “We did exercises like writing things on pieces of paper—I can’t even remember what—and burning them in the fireplace. But eventually, we realized it was better to just ask people why they were there and let the conversation take off. Sometimes it’s sad, sometimes it’s really funny, but it’s always interesting.”

Now more than 11,000 Death Cafes have been hosted in 73 countries, bringing gatherers to actual cafés, living rooms, cemeteries, and catacombs—and, more recently, virtual meeting spaces—to discuss such topics as dying loved ones, funeral planning, and what really happens in a crematorium.

Participants are usually strangers, which can help encourage openness about this discomfiting subject, and food is essential, says Mooney, Death Cafe’s U.S. leader: “We’re more okay talking about death if we’re nourishing ourselves at the same time.” (Adds Reid, “There’s something life-affirming about cake.”)

In 2017, at age 44, Underwood collapsed suddenly from a brain hemorrhage caused by an undiagnosed case of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Little did he know his death would become part of his life’s work: reminding human beings that time is precious. “After I host a Cafe, I ask the participants whether their views on death changed as a result. They usually say, ‘No, but my views on life have,’” Mooney notes. “Pope Paul supposedly once said, ‘Somebody should tell us, right at the start of our lives, that we are dying. Then we might live life to the limit, every minute of every day.’” — Amy Maclin

To find a Death Cafe—or learn how to host your own—visit deathcafe.com.

It Worked for Me

Tragedies are easier to process if there’s a reasonable amount of justice: a villain to apprehend, or a satisfying punch in the face. I could not strike back against the heart attack that killed my 44-year-old husband, Scott, in 2015, right in front of me, with a sudden violence that seemed like murder. You know who does get justice, though? John Wick. The Equalizer. Myriad shirtless Patrick Swayze characters. In the immediate numbness following Scott’s death, I found a crude but gratifying symmetry in watching Keanu kick puppy killers, or Denzel topple those who preyed on the weak, or Swayze beat up everybody. It makes sense: Someone hurts someone else; you hurt them in return. In real life, things are fuzzy and unfair, but on the other side of the screen, where the score is settled with fists and feet, the bad guys pay. Bloodily. And that helped me. — Leslie Streeter

Checkout Time

An advance-planning evangelist preaches the gospel of being proactive.

Do your parents have a storage unit? What’s your aunt’s Facebook password? Where does your sister keep her diaries? These may seem like minor concerns—but when a loved one becomes terminally ill or dies, knowing those simple details can take the mayhem out of mourning. “When a relative is in the ICU, you don’t want to be wondering who’s got the spare garage key,” says Amy Pickard, founder of the end-of-life planning business Good to Go.

A former freelance film and TV producer in Los Angeles, Pickard made her way into this work after her mother died suddenly in 2012, without a will. “I became an accountant, detective, lawyer, and housecleaner overnight,” she says. “I was in a grieving hellscape and grappling with cosmic questions while also trying to figure out which electric company my mom used.” The grueling estate-shuttering process took Pickard a year and a half. In 2015, she started Good to Go in order to help others avoid leaving behind, or having to deal with, a similar mess. “One friend calls me a death concierge,” she says.

A typical Good to Go session involves a potluck, cocktails, and a cheeky rock ’n’ roll death-themed playlist. (“Another One Bites the Dust”? Check.) Then guests—a gaggle of BFFs, a group of terminally ill seniors, a cluster of moms and daughters—are presented with the Departure File, a 50-page manual filled with every topic Pickard wishes her mom had addressed that isn’t covered in a will. It’s also available on her website (goodtogopeace.org). Though not a legal document, the guide covers ground both practical (Who should get your jewelry? Will someone inherit your pet?) and spiritual (Who should preside over your funeral? Do you even want one?). “People can be intimidated by how extensive the file is,” Pickard says. “But I say, as overwhelmed as you feel, imagine your family winging this without your instruction. Advance planning is an act of love.”

Pickard’s dad attended an early Good to Go gathering in 2015; he died a year later. “I remember standing in the ICU feeling relieved because I was rock-solid on what he wanted,” she says. “He prepared perfectly, so when he was on his deathbed I could just hold his hand. Thinking back to the peaceful look on his face still makes me cry.” —Zoe Donaldson

Till Kingdom Come

A cat, a breakup, and the (cold) comfort of everlasting love.

By Deborah Way

To understand why my cat Stinky has lived in my old boyfriend’s freezer for 18 years, you have to understand Stinky. And my old boyfriend.

There was no greater cat. He was my gateway to all cats. He appeared one day in the weedy lot we rented behind our loft in industrial Boston, dozing in the sun on the hood of the Rambler convertible we stored there. A wide, handsome face, black spots on a white coat, the filthy white of a stray who exulted in rolling in the soft pebbly grit that collects beside the curb on city streets. He agreed to live with us. He came when we whistled. He walked anywhere on a leash.He rode in the car, supine on the back ledge, bringing joy to every passing motorist who noticed the cat going 70 down the highway. One time when we flew with him, the ticket agent was so charmed she upgraded us all to first class. The flight attendants served him cream. He was king of the world.

When I went to grad school in Ohio for two years, Stinky came along to keep me company. This was a gift from my boyfriend, because as much as I loved Stinky, he loved him even more. And because like so many kings, Stinky had a tragic weakness: When he came to us, he was FIV positive. We knew he would die of cat AIDS; we just didn’t know when.

My boyfriend was a king, too, a Leo by birth, a wonder who could do anything: wire a house, rebuild a car engine, multiply large sums in his head, understand tax law, teach himself Chinese, paint your exact likeness, forgive you when you got drunk and angry, sew you a brown crushed-velvet dress with wings the year you wanted to be a bat for Halloween, let you leave him when you fell in love with someone else yet continue to be your best friend.

It was the hardest and saddest of all partings. I left them on a frigid, windy day in January, having gone back to Boston to pack all my belongings for the one last drive to Ohio. Six years later, Stinky died in the night, exhaling his last breath as he lay on his best friend’s chest.

My old boyfriend couldn’t bear to bury him, to never see him again. Instead, maker and fixer that he was, he decided to taxidermy him, a plan I wholeheartedly endorsed. He covered him with a bandanna, placed a penny on top for good luck on the way to heaven, zipped up the plastic bag, and put Stinky in the freezer. And there he still is. Not just because some of us are legendary procrastinators, but because pets hold all the feelings it would break our hearts to feel. Keeping him on ice is a way of keeping grief deferred.

It Worked for Me

In April, we rented a cabin in the woods to be near our daughter, who was pregnant. I am an urban animal, so this was a big change for me. Our son-in-law bought us a couple of bird feeders, including one for hummingbirds. I boiled sugar water for their nectar and hung the feeder near the deck that overlooks a pond. I set up my “office” on the deck, but I was preoccupied with my daughter, whose restaurant was failing; my husband, whose job was in jeopardy; and a weekly Zoom with a dear friend who was dying alone halfway around the world. So I found myself watching the hummingbirds. I watched as they hovered like tiny helicopters and drank and darted, their iridescent green wings and ruby throats flashing in the light. I learned that they are the only bird that can hover, and that they spin nests with spider silk. I still gaze at them for hours, suspended in time as we are suspended in this strange stasis, yet vibrant and alive. Their tiny feet cannot walk even a few inches. Instead, they must fly. —Mary Morris

Your Condolences

With these time-tested expressions from across the globe, you’ll never find yourself at a loss for sympathetic words.

Afghanistan: May life be upon you.

Egypt: May her spirit remain with you in your life.

Turkey: May she rest in heavenly light.

Greece: May you live to remember her.

Germany: You are not alone in this difficult time.

France: Peace to her soul.

Spain and Latin America: I am with you in your pain.

Zimbabwe (Shona): We are devastated with you.

Jewish: May her memory be a blessing.

—Eleni N. Gage

Hard Pressed

How widow Andrea Bennett juiced her way out of grief.

One week after the Richland County coroner’s office lifted Ken from our backyard hammock, I drove into the Blue Ridge Mountains cradling a cardboard box of my husband between my knees. We drove into the hills above Greenville, South Carolina, to Fred W. Symmes Chapel, watercolor peaks in the distance. Ken had brought me here years earlier and tried to still his shaking hand as he presented me with a ring. Later we gave the chapel’s name to our daughter, Emily Symmes. Now I would leave his ashes here. Then I would buy a juicer.

First I shopped late-night infomercials like they were selling religion, because

I needed a covenant with a 30-day money-back guarantee. I was lost—until televangelist Jack LaLanne, the Godfather ofFitness, promised me I could juice my way back to vitality. Juice, specifically from the Jack LaLanne Power Juicer, could reportedly help prevent heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and high cholesterol. If Jack’s 90-something-year-old body could cartwheel down the street fueled by bushels of liquefied produce, who knew the direction my life could now take?

Converting to the teachings of Jack LaLanne seemed no more bizarre than whispering to a box of charred detritus and dumping it off a cliff. Ken had a certain sense of melodrama; he would have loved his memorial, the way the wind suddenly turned and blew him back so that little bits of him lodged in my hair. It served me right. “You ran away,” he would have said. “I hope I flew up your nose.”

One woman I know bought a red Porsche on the way home from her husband’s funeral. She was driving by the dealership in her sensible Camry, and there no longer seemed to be a reason not to buy a sports car. Her logic made perfect sense to me—even more so when, years later, I read about a study suggesting that making purchasing choices can actually help reduce “residual sadness” by giving those experiencing the emotion a sense of the control they’ve lost. Of course, I didn’t know anything about that study back in 2010 when I decided I would pulverize vegetables into a magical elixir that would retroactively detoxify my marriage. All I knew was that pushed to the brink of my sanity, I became the kind of dangerous-risk taker who turns to organic carrots.

Jack and Elaine LaLanne were in this together. There was something uplifting about the joking patter of two senior citizens cramming whole potatoes and celery into something resembling a countertop wood chipper. Elaine juiced five vegetables in 17 seconds as Jack timed her on a stopwatch. These two had marriage figured out. Jack thought I should want a quiet motor. I didn’t. The crack of a blade obliterating a carrot might drown out my guilt and relief.

It took me weeks to commit to a juicer, and the actual purchase was anticlimactic, mostly because it interrupted my shopping for juicers. I bought the Breville JE98XL Juice Fountain Plus 850-Watt Juice Extractor, because a longer name with more numbers yields superior vitality. It was an act of betrayal, but I would always be thankful to Jack and Elaine.

The juicer did not absolve me. It did not fix everything—or anything—that had gone wrong in my marriage.

My husband’s voice in my head was right: After he cocked a Glock pistol filled with hollow-point bullets, waved it at our baby and me, pointed it at his head, checked into a psychiatric facility, then got out and looked for his gun again, I did run away from our marriage. I picked up my baby and packed my laptop in her diaper bag. I parked my car in a vacant lot, turned off my cell phone, and flew us to Utah. I barricaded myself in my parents’ house, afraid he would come for us. He didn’t. “Goodbye, my love,” he texted.

This is not something he would normally say. I dialed the police, who later called me from our backyard. “Your husband’s in the hammock, and he’s feeling pretty good,” the officer said.

“I think he’s taken something. This isn’t right,” I insisted.

“Ma’am, this is his property and he’s telling me to leave.”

“Something is wrong!” I screamed. “Help him!”

“I’m sorry, ma’am.”

Maybe Ken thought that since one Ambien and a beer could make him feel good, 26 Ambien, 30 Lexapro, and a case of beer would work even better. Three days later, the police found him where they had left him. His wallet had fallen into a puddle underneath the hammock.

When the Breville JE98XLJ uice Fountain Plus 850-Watt Juice Extractor arrived,

I memorized its parts and marveled at the titanium-reinforced disc and micro-mesh filter basket designed for optimum nutrient extraction.But turning vegetables into redemption is messier in real life.

The juicer did not absolve me. It did not fix everything—or anything—that had gone wrong in my marriage. As for the LaLannes, when I last checked, Elaine was writing a book that teaches baby boomers how to live longer. Jack eventually died of respiratory failure, though he exercised right up until the end. The Breville now lives on a shelf in my garage, but it gave me something to aim for—the promise of an optimized life, healthy enough to blot out the trauma, for a time. It did its job. It did enough. —Andrea Bennett, a former magazine editor, is at work on ahistorical novel.

Greener Pastures

The environmental footprint of conventional burials is huge: the metal and concrete put underground, the forests of hardwoods used to build coffins, the toxic chemicals in embalming fluid. But the graves at my company’s natural-burial sites are dug by hand, and the individual’s untreated body can be placed inside anything biodegradable: a shroud, a pine box, a basket, or absolutely nothing. This was pretty much the only way we cared for our dead until the Civil War, when formaldehyde and embalming came into use so families could bring soldiers back from the battlefield across long distances.

In a conventional burial, mourners watch a mechanical device lower the casket. That can be traumatizing—there’s a sense of disconnection with the person you’ve lost. But families can participate in every aspect of natural services: They can carry their loved one to the grave, help place them inside, and fill the grave with soil. The intimacy of this process evokes raw emotion, and that’s cathartic. Afterward, people look changed.

In the natural-burial world, we can also mix cremated remains with soil and plant a tree. Or incorporate them into a structure called a reef ball, which is placed on the ocean floor, where it becomes a home for coral and sea creatures. What impacts me most is showing families that embalming fluids and concrete vaults and steel caskets aren’t necessary: You come from the earth, you go back to the earth. And maybe become part of something larger. —Ed Bixby, owner of the Steelmantown Cemetery Company

The Medium Is the Message

Craving contact with the beyond, Lucy Kaylin asked an expert to place a long-distance call.

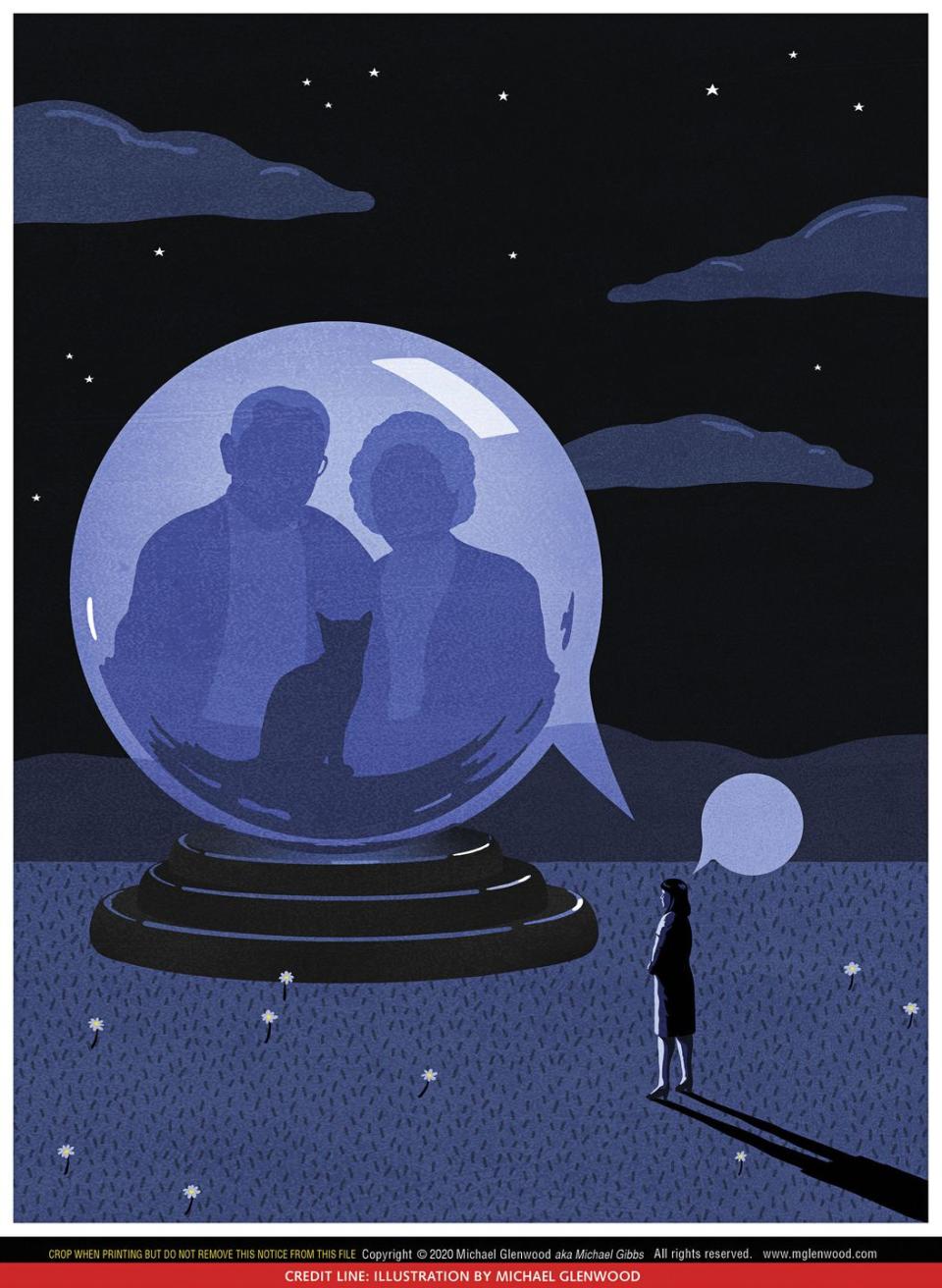

It’s sweet to think, isn’t it? After your loved ones are dead and gone—reduced to a pile of bone fragments in a box—there might still be a way to connect.

I’d lost plenty of people I cared about through the years—to age, AIDS, cancer, accidents, drugs, drink, and so on. But it wasn’t until both my parents had died that I began to think about reaching out.

My dad was such a potent character—a lanky jazz cat, equally versed in boxing and Tolstoy; our conversations about politics, Buster Keaton, civil rights, Cubism, the triangle offense, bebop, and finding work you love were direct and intense and continued unabated until he drew his last rasping breath. I missed him. It didn’t seem possible that someone so vivid could have simply gone poof, even at 95. My mother, who’d died six years earlier, was subtler—a lover of psychology, Bach, Abyssinians, herself a bit sphinx like. She was generous and kind and widely admired. But I also thought she seemed lost in thought much of the time. Unsettled. For me, anyway, it made her difficult to access.

A colleague suggested a medium he knew: Theresa Caputo, a.k.a. the Long Island Medium, star of the TLC show of the same name and bestselling author of, most recently, Good Mourning.

When I’d first thought about taking this journey, I pictured shaman-y goodness—a bald head, chimes, preternatural calm. Not a sky-high bouffant and squared-off acrylic nails. But I’d read enough to know there isn’t a certain “type” who can connect with the spirit world. You’re either on that frequency or you’re not.

Caputo’s readings work something like this: As a way of “clearing the space,” she burns some sage, meditates, and says a prayer. Then she imagines whatever negative energy she’s holding draining out of her “untilI become translucent and can fill myself with God’s white light.” Of any and all comers, she asks only for information “that will help people move forward in the physical world with peace and comfort.” No settling of scores or rehashing of tiffs. The goal here is closure.

At the time of my reading, we were sheltering in place, so Theresa and I FaceTimed. I was in New York City; she was at her house in suburban Long Island, her mom out back by the koi pond social-distancing with friends. Again, not what I’d pictured, but what did I know? Before we began, I was assured Theresa knew nothing about me beyond my first name.

Suddenly my screen filled with her excitable face and platinum nimbus, her bare shoulders visible through the cutouts in her blouse. (In truth, the nimbus was a little less platinum than it is on TV, and shockingly, the acrylics weren’t on—during Covid-19, salon visits were on hold. “My kids can’t believe how tiny my fingers are,” Theresa said.)

She launched in. “I’m going to say this to you: Sometimes before I read, I feel things, and today I felt upset—that someone died, or the way someone died? I felt it when I woke up this morning. Then it came back when we started talking. I can’t get rid of that. Maybe how things were handled?”

She quickly switched gears. There’s an aspect of air traffic control to what Theresa does—she picks things up on the spiritual radar and deals with whatever’s coming in. At times I felt like she was fishing, like when she asked me how I connected to the number seven. Okay; my daughter was born on August 7, but I felt like I could probably find a way to connect with pretty much any number.

Then Theresa scribbled something on a legal pad. “Is there a child named or someone? The form of a name or a last name?” Yes, I said—my son’s name is a one-letter variation on my mother’s maiden name.

“That’s it,” she said, turning around the pad on which she’d Sharpied child/son.

“You have quite a few loved ones stepping forward,” Theresa said, zeroing in on some mother energy. Then, both parents—“standing together, holding hands”—something I never saw them do in life.

“Your mom’s doing all of the talking,” Theresa said. “She’s shushing your dad”— again, something rarely witnessed on the mortal plane.

Whatever happened on that FaceTime call, it made me feel closer to my mom, if only for an hour.

Theresa’s eyes widened. “Oh, your father is funny! He just keeps coming forward,” she said, giggling.“He’s so funny!”

I knew what was happening: My dad was flirting with her. While my cultured, circumspect mom was his perfect idea of marriage material, my father had a huge weakness for warm, fun, outsize blondes like Theresa. I’d seen him chat them up a million times in restaurants, at parties, on sidewalks.

She cocked her head—listening again—looking puzzled. “Anything funny or different about a burial?”

Depends on your definition of funny: My sister’s family and mine had met at our parents’ house at the beach and ladled their remains into red plastic go cups. Our kids, in their teens and 20s, toasted their grandparents and threw back shots of whiskey. Then we all stood at the water’s edge and flung the ashy mixture onto the waves. I was pretty sure our funky DIY ways on such an occasion weren’t anything Theresa could relate to.

“But was there something else?”she said, still looking confused. “Did something else get released?” Well, yes, it did. When my dad went into the nursing home, we took his cat, a sweet old gal I referred to as Grandma. She died 13 days after he did. We’d had her cremated, too, then mixed her remains in with theirs.

My parents loved Grandma. Said Theresa, “They want you to know they approve of how it was handled.”

That was a relief—at the time, it hadn’t occurred to us that our parents would see how we handled it, let alone weigh in.

Suddenly Theresa grabbed at her chest, gasping for air: “I’m having trouble breathing. Feeling pain here. How did your mother die?”

Pulmonary issues that led to heart failure.

“Your mother is saying she wasn’t herself at the end.”

My eyes welled up.

Our mom died alone. It happened in the middle of the night—the attendant sat the nursing home hadn’t given us any warning; we weren’t able to get there in time. We’d seen her a day and a half earlier, and she was struggling terribly. Unlike with our dad—both my sister and me at his bedside, holding his hand and stroking his head—we weren’t able to comfort her. It’s something we have had to live with.

“She didn’t want you to see her like that,” Theresa said. “She says it happened the way it should have.”

Did she really, though?

Yes, our mother was incapable of holding a grudge—it would be very her to make a cosmic effort to let her daughters off the hook. But was Theresa giving me the gift of some dearly wished-for but unprovable thing?

In the end, it didn’t matter. Whatever happened on that FaceTime call, it made me feel closer to my mom, if only for an hour. And how lovely to think they might be together up there, holding hands, peaceful, forevermore.

I just hope they connected with Grandma.

It Worked for Me

When I lost my closest friend, grief struck me in waves. No sooner would I get my head above water than I was pummeled by another random breaker pulling me under again. I could find no way to the surface. Distractions that normally lifted or shifted my spirits—a hike, a hot bath, a glass of red wine—didn’t help. There were no hacks. So I turned to Rumi, who instructed that “the cure for pain is in the pain.” In other words, grief requires grieving; unlike anger, it does not lend itself to management. Only when I allowed myself to fully experience the pain and the missing did I begin to get my bearings. Tears were shed, lots of them, a consequence of loving with abandon. Now, 15 years later, when I think of my friend, the memories are more sweet than bitter—times spent together bobbing in the ocean, reading aloud, and confiding our secrets—the joy of allowing someone wholehearted access to my soul. — Adrienne Brodeur

Crowning Glory

A loss led one woman to a hairstyle she'll keep forever.

By Rachel Anne Warren

Eleanor had a black turban and gleaming smile that made her frail frame more grand. But she would have been difficult to overlook regardless: Jaundice gave her skin an otherworldly glow. Suffering from stage IV pancreatic cancer, Eleanor had less than a few months to live. She’d lost her hair after her first round of chemotherapy, and she required my services. “We need a white wig,” she said. “For my funeral.” Her granddaughter beside her only nodded, her eyes wet and wide.

I’ve been a traditional wigmaker for three years, fashioning pieces for women undergoing gender transition and experiencing myriad medical conditions. But I’d worn and altered wigs for more than a decade before that: I have androgenic alopecia that became noticeable in my early 20s, after a stressful year that started with leaving college and ended with caring for my best friend, who was suffering from a rare form of leukemia. So my clients and I have hair loss—that disorienting, alienating, confidence-destroying calamity—in common.

Eleanor had proudly lived her entire life where she was born and raised; she and her late husband had featured prominently in their hometown parade. She had also once taken pride in her hair, a full, three-inch permed halo that rarely budged but was soft to the touch. Pearly rinses ensured it shined in the right shade of frost. Eleanor had painstakingly preserved her beauty—and I would honor that.

Before coming to see me, she had tried ordering wigs online; each looked more like Halloween headgear than the last. But none of our studio’s manufactured options suited her. So with measurements and reference photos by my side, I spent a week with a wig block in my lap, pinning a wide strip of fine lace taut, stitching nearly invisible thread along the edges, knotting individual hairs. I knew how carefully Eleanor would inspect it.

When she returned a week later to try on the wig, I anxiously spun her chair, offering a handheld mirror. She poked a narrow finger along her forehead at the strands. “I have hair!” she said. “I can go out in public!”

Women whose bodies have been ravaged by disease can’t undo the damage. But they can apply a trusted lipstick, paint their nails, put on a dress that’s transformative, wear a wig: small acts that might make their physical self feel more like home for a while. An entire lifetime can’t fit into a casket, but the right color heels or a swooping curl just might ease the journey.

It Worked for Me

I found out about my miscarriage in an email, the morning after my ultrasound. Spontaneous abortion. I was told that a heating pad, aspirin, and rest would help soothe the pain. When I spoke to a friend, she asked, “What else does your body need?”

I was used to stifling sorrow, shooing away sadness— what I needed was to scream. “So do it,” my friend said. We lived in New York City, where every inch of space is shared with strangers, walls are paper-thin, every uttered word has a witness. She offered up her rooftop pool. “Being underwater is like being in space— no one can hear you scream,” she insisted. I felt embarrassed at first: Toddlers throw tantrums and wail. But I needed an outlet.

So I forced myself under, pushing against the side of the pool. The tears disappeared in the chlorinated water, and the wails rose up as bubbles. Submerge. Scream. Cry. Rise. Repeat. Each time, I resurfaced lighter. — Jessica Ciencin Henriquez

Parting Gift

As the end draws near, Valoria Walker’s work begins.

When my mother was dying in 2011, the hospice nurses told me they were giving her “comfort care.” I didn’t realize that in my mom’s case, this meant heavy sedation; I thought they were just allowing her to rest. I never got to say a proper goodbye. The nurses didn’t see Mattie, the mother and grandmother—they just saw another soon-to-be-gone patient. I believed that no one else should ever have to feel as distraught and neglected during their loved one’s passing as I did. My mom’s death birthed my career as a doula.

You’ve probably heard of doulas who help pregnant women through labor and make sure their specific needs are met. I’m an end-of-life doula: I help people with the work of dying. As a trained support companion, I honor their emotions and meet them exactly where they are in their final hours. I also tend to details in the last days, or even months—the medical plans and funeral arrangements—and make space for important conversations and requests. For instance, Miss Ann told me she wanted to be buried in her church finery, complete with red hat and white gloves. She didn’t talk about that with her children—maybe such a discussion would have been too painful and it was somehow easier with me. I took Alice outside to feel the sunshine. June just wanted her hair fixed one final time. As a fellow African American woman, I understood well why that was so important.

There’s no set of hard-and-fast rules for this work. I just follow my clients’ lead until the end. Occasionally, I take time off after a death if I’m particularly close to the client, like I was with Miss Ann and June; I need space to process my own grief. But before long, I’m ready to help guide the next person through their final passage. — As told to Kelly Burch

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.

You Might Also Like