Gregory Doran: my memories of a life with Antony Sher

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I have two indelible images of my life with Tony which oddly correspond. One of them is just a week old. Big Rock is a white granite outcrop that squats like a giant toad, at the end of a beach in Sea Point, the suburb of Cape Town in which Tony was born. At high tide, you can jump from the rock into a pool below, as green as malachite, and as exhilarating as a cool flute of Pol Roger. Tony loved that jump. That’s why he chose this place. That’s why we are here. His family and I clambered up, each scooped a handful of his ashes, and scattered them scintillating in the bright sea air.

The other image is from a soggy December morning in Islington in 2005 when, after 18 years together, we were made legal. We became civil partners on the first day that same-sex couples were allowed to do so. Tony couldn’t believe that within his lifetime, gay rights should have come so far. As we emerged on to the steps of the Town Hall, our friends and family pelted us with rice and confetti.

Confetti and ashes. In fistfuls, flung into the air.

We discovered that Tony had cancer out of the blue, in June, just before his 72nd birthday. There were two lesions, one the doctor said, which was the size of a satsuma.

Tony told me he was going to write about this whole experience, to keep a journal (as he had so many times before). He would call it “The Year of the Satsuma”, and he said he had the first line: “When the theatres closed, I was playing an old Shakespearian actor dying of cancer. Now I am an old Shakespearian actor dying of cancer. Who says actors don’t take their work home with them.”

Tony knew what was coming. During the preparation for that play, John Kani’s Kunene and the King, he spent many hours researching what cancer did to you.

That research informed Tony’s decision not to take any treatment – drugs that might extend his life a few weeks, but which would inevitably bring distressing side-effects: nausea, diarrhoea, etc. He had seen his late sister Verne go through just that too recently. Rather than go into hospital, he wanted to spend the brief time allotted to us at home, in our beloved house, on the Welcombe Hills, in Stratford-upon-Avon.

By the end of August, we knew the cancer was inoperable and terminal, (one prognosis gave him three to four months), and at the start of September I requested compassionate leave.

On my birthday in November, as he woke up, he took both my hands and said, in the hoarse whistle that that great voice of his had become: “I made it to your birthday”. He had written two cards, just in case: one if he did, one if he didn’t get there. He died a fortnight later.

In truth, the RSC allowing me to take compassionate leave gave us time. But not enough time. We did manage to sort his archive, a 50-year career of his annotated play scripts, now all collected in the cabin trunk he brought over with him, as a shy 19 year old, from South Africa in 1968.

We collected together all the manuscripts of his novels, the typescripts of his journals, and stored a lifetime of diaries in a very large case. His artwork is now all catalogued too, from some precociously accomplished biblical scenes drawn as a teenager, to the sketches scribbled in rehearsal, to the portraits and the oil paintings.

The Audience is a huge 6ft x 7ft canvas of an auditorium filled with important people in his life: heroes and villains: Mandela, Tutu, Albie Sachs; as well as monsters (many of whom he played) like Hitler. Artists he idolised: Dalí, Bacon, Hockney, Michelangelo. Actors he admired: Marlon Brando in The Godfather, Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice, Peter Sellers in Dr Strangelove, Fiona Shaw, Mark Rylance, Simon Callow, Judi Dench, Ian McKellen. And there, glowering from the canvas, Olivier as Richard III. He called it a dream map of his life. And there are parts he played, too. Arnold the drag queen in Torch Song Trilogy; Singer in Peter Flannery’s play, Stanley in Pam Gems’s play at the NT. Macbeth (with Harriet Walter), Leontes, and Shylock.

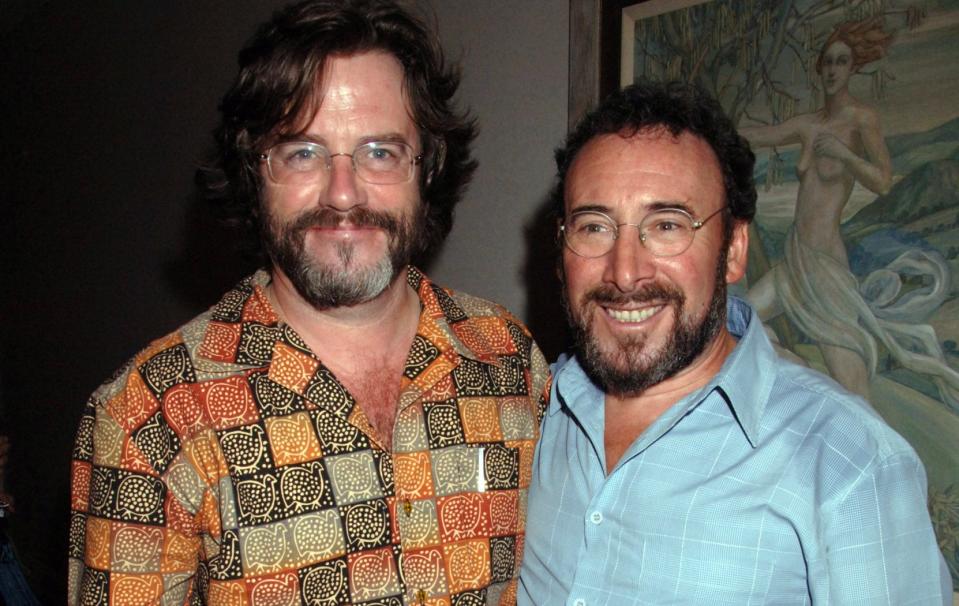

Tony was playing Shylock in Bill Alexander’s production of The Merchant of Venice in the 1987 season at Stratford when we first met. Tony gave a volcanic performance, a white heat which I witnessed in close-up every night. I was just a young actor, playing Solanio, and I spent much of my time voiding my rheum on Shylock’s beard, and trying to beat him up with a stick. Until one wet Thursday matinee, when I was clearly (as they say in the business) “phoning it in”. Before I knew it, Shylock had grabbed my stick and was chasing me around the stage.

That taught me a lesson, to be in the moment. One of Tony’s great gifts as an actor was to be completely there, utterly present on stage and thus mesmeric, with the compelling quality of compression, of always having more power held in reserve.

During the shortening days of autumn, we were able to look back on some shared memories. We walked together on the Great Wall of China (on the RSC tour of Henry IV and Henry V).

And we walked together in one of the first ever gay pride marches in Johannesburg (during a National Theatre Studio visit to the Market Theatre), as American zealots (shipped in specially for the occasion) held up their bibles and shouted “Perish!” at us from the sidelines.

But our souls always lifted together watching wildlife. Trekking into the forests of Uganda, on our honeymoon to sit in the presence of mountain gorillas. Bathing elephants in a tributary of the Ganges.

Tony meant a great deal to a great many people. Many of them wrote to tell him how much he had inspired them: as an actor, in his writing, in his life. I am glad he got to hear some of those tributes before he left. When news that he was ill broke in the papers, many printed appreciations of his talent. “It’s a bit creepy,” he said, “like reading my own obituaries”. “Maybe,” I said, “but at least they are all five-star raves.”

As I try to come to terms with Tony’s loss, it is Lear’s line about Cordelia that makes most sense to me. “Thou’lt come no more. Never, never, never, never, never.” I can still hear Tony saying that line: each repetition an attempt to articulate and comprehend the finality of death. Now that he is gone, it’s not consolation I yearn for, but acceptance.

An evening of programmes dedicated to Antony Sher begins at 7pm tonight on BBC Four