Do Great Actors Make Great Novelists?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

No, they don’t.

Apologies for sort of spoiling the premise right up front, but that’s the answer. Great acting talent does not necessarily translate to literary excellence. But the reason this is true has nothing to do with acting and everything to do with novel-making. Constructing a complex narrative with tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of words is really, really—really—difficult; merely completing a draft of a novel is a major accomplishment. Then the revision process demands not only complete overhauls, but also infinitesimal tweaks that can sometimes cause reverberations throughout the rest of the story. A novelist must keep all of this in their head, balance the bewildering intricacies of one’s own novel with the endless possibilities available for improving it. The writing, revising, copyediting, marketing, publishing, and promotion of a single novel can take many years. Debuts are rarely a novelist’s best work, and often this is because many of the “rules” of fiction are notoriously difficult to articulate, let alone learn in practice and eventually wield with grace.

The result of all this is pretty straightforward: novelists are the only great novelists (and even they are rarely great). So, no, actors don’t make great novelists, but that’s no slight on actors. Saying that great actors don’t make great novelists is basically like saying that great dancers don’t make great architects—yeah, but that’s only because dancers aren’t architects. To be great at something necessitates not being great at much else.

Some actors are, of course, accomplished writers and skillful storytellers; their prose can be witty and lively and engrossing. But as only a handful of actors have ever written more than one or two novels, most of them never develop the abilities underneath the abilities, the kinds that only those truly dedicated to the project have the time to discover.

Despite this legacy of failure, it’s a surprisingly rich tradition, the actor-novelist, from Marlon Brando and Janet Leigh to Kirk Douglas and Sidney Poitier to Carrie Fisher and Jim Carrey. Hell, even then 25-year-old Macaulay Culkin put out a novel during his Party Monster era. Actor-novelists are an eclectic amalgam of stars, a real mishmash of Hollywood history: Krysten Ritter, Gene Wilder, David Duchovny, Molly Ringwald, Ethan Hawke, Pamela Anderson, Steve Martin, Sylvester Stallone, Blair Underwood, Mickey Rooney. (For the sake of this piece I’m only discussing novels, as in book-length fictional narrative, and not memoirs or story collections or volumes of poetry.)

$22.75

amazon.com

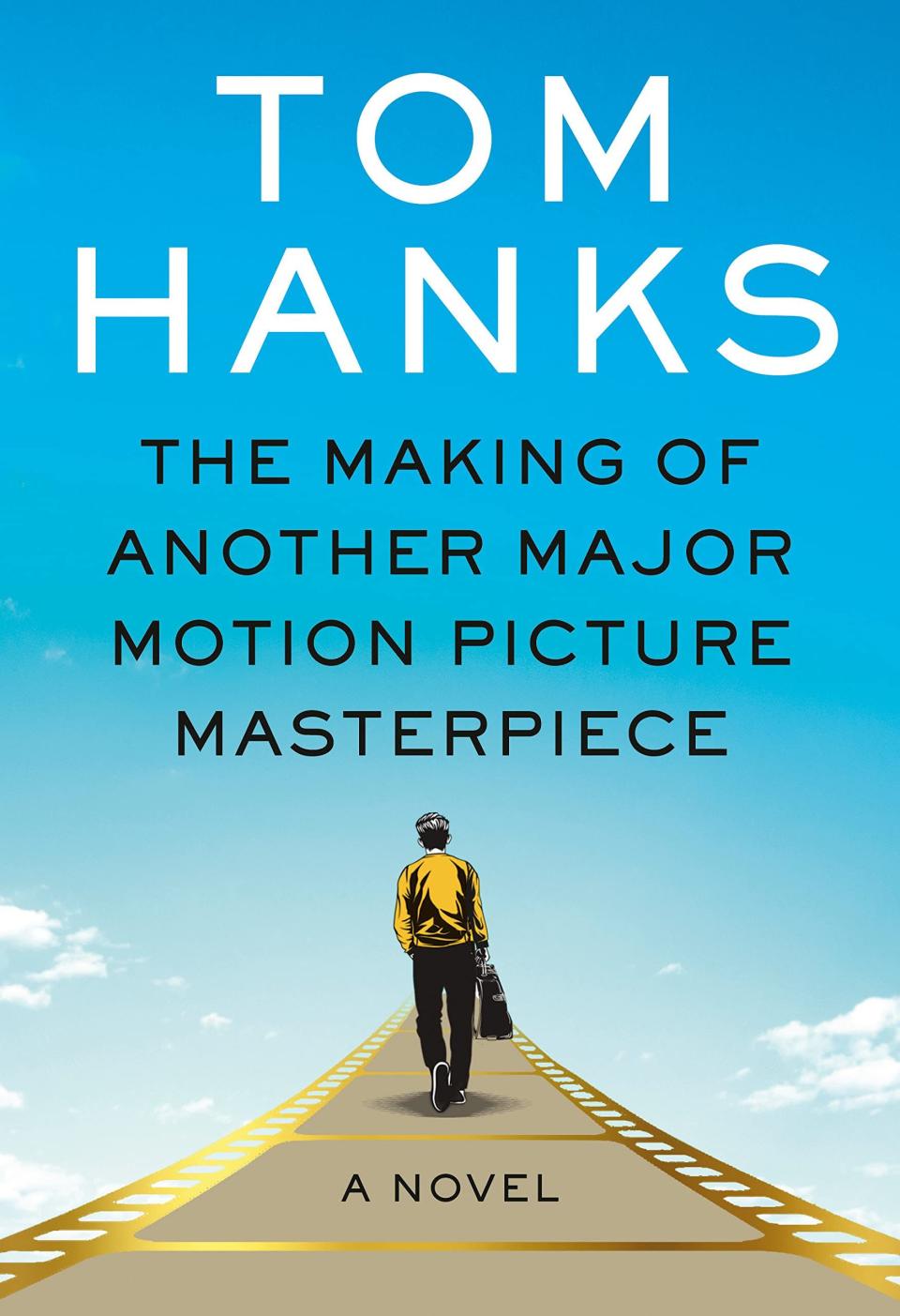

The next Hollywood icon to take up the mantle of novelist—and who serves as occasion for this piece—is Tom Hanks, whose debut novel The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece hits shelves today. In terms of acting, you can’t get much better than the two-time Academy Award-winner. Furthermore, Hanks has written and directed for film and television, and he previously released a collection of stories, Uncommon Type. He is, in other words, no narrative slouch. Will Hanks be the exception? Will the greatness of his acting coupled with his previous experiences as a writer be enough to make his first novel a masterpiece?

Again: no. He isn’t, and they won’t be.

But, that doesn’t mean that The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece isn’t an impressive accomplishment, or that it isn’t a fun and charming celebration of cinema. And what’s more, his novel is, in many ways, the prototypical actor’s novel, a handy reference point for the themes, mistakes, and creative choices of Hollywood stars when they deign to step down from the hallowed pedestal of the spot-lit stage to join us lowly writers in the miasmic pit of self-despair known as literature.

The Cardboard Carnival

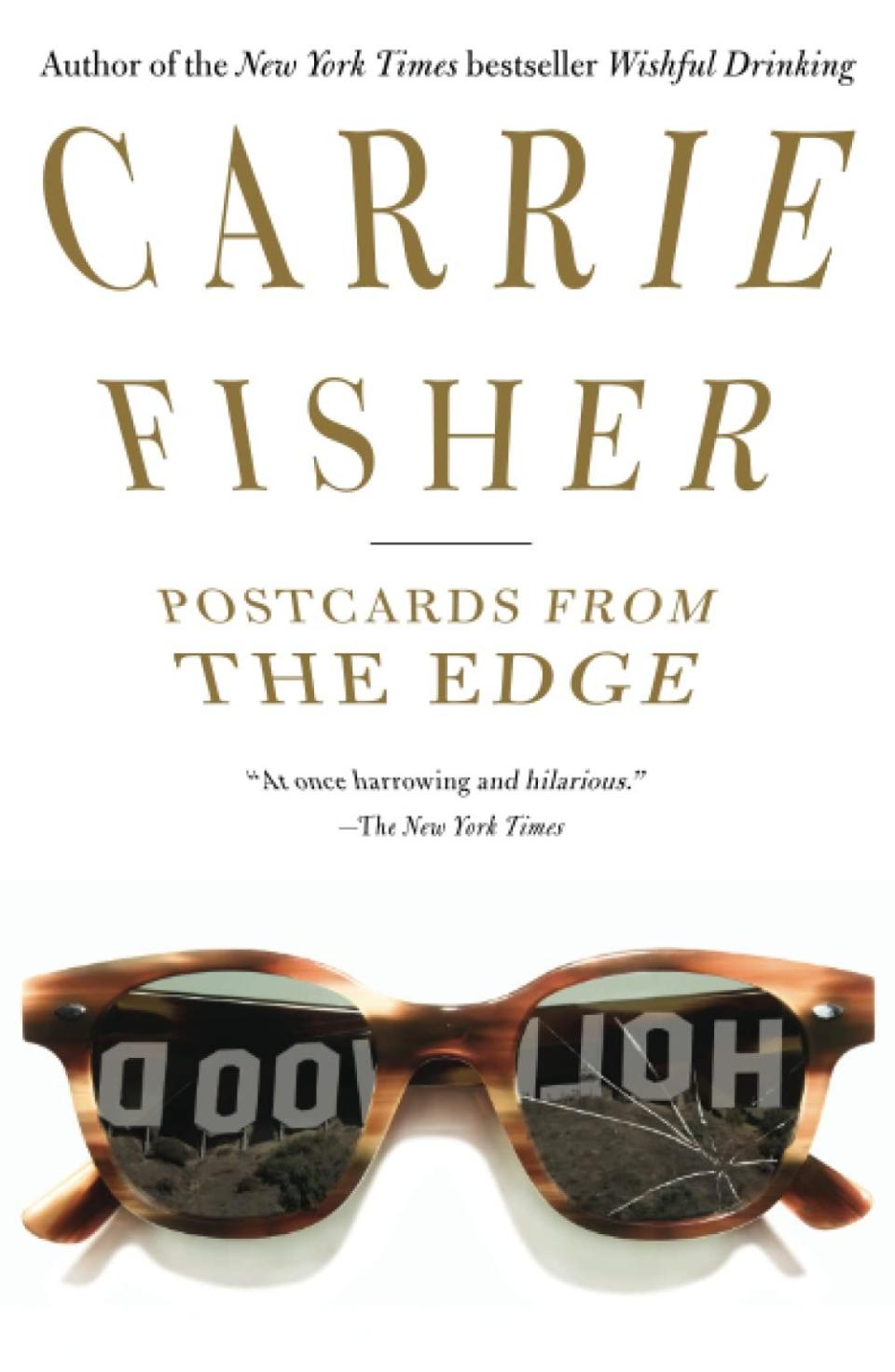

It should come as no surprise that the one of the most frequent subjects in novels by actors (if not always the precise setting) is Hollywood itself. Sometimes, that looks like Carrie Fisher’s Postcards from the Edge, which both satirizes the solipsism of the town and insightfully explores the effects such a place can have on its glitzy denizens. Suzanne Vale, a stand-in for Fisher, attends a drug rehab, dates a pompous producer, and tries to navigate the Darwinian vagaries of an acting career. Fisher’s novel can be a bit too on-the-nose—for instance, Fisher reproduces the inner monologue of a fellow rehabber named Alex as he hits rock bottom, refuses to accept that he’s an addict, then eventually leaves the clinic and relapses. While accurate, it also does that thing where Alex perfectly articulates the process of recovery, like a template given to the newly sober. Fisher’s sequel, The Best Awful, published sixteen years later, focuses on Vale grappling with bipolar disorder, the complexities of medication, and the responsibilities of parenthood. It’s a richer and more rarified glimpse into the struggles of mental health and its underlying relationship to behavior and identity.

Another kind of Hollywood novel is the scandal-ridden, peek-behind-the-curtain tale, like Janet Leigh’s The Dream Factory, about a high-powered woman in show business named Eve who has kept “an appointment book” over her long career, filled with the juicy secrets of Hollywood’s elite. As Eve lies dying in a hospital bed, the industry wonders what will become of the diary and who will be implicated if its contents are revealed. It’s a truly abysmal book. Not only is the writing poor (“The old adage ‘It never rains but it pours’ certainly proved itself once again”) and the insights glib (“He’s so wrapped up in himself and his career, I don’t think he’s capable of caring deeply for someone else”) and its plentiful dialogue a veritable forest of stiff wood (“Yes, it is all right to feel emotion, love, passion again. It’s not only all right, it’s healthy and advantageous and normal”), but there’s a quasi-religious overtone to it that’s about as subtle as a siren. Eve’s niece Cassandra, after many selfish love interests, finally finds a nice guy named Jim Carpenter (there are also characters named Ruth and Abraham); the people worried about the secrets in Eve’s journal end up doing some “soul-searching” after she dies and lean on “God’s will” for support. Leigh’s novel is both unconvincing and moralizing.

$11.59

amazon.com

Hanks, in The Making of Another Motion Picture Masterpiece, attempts something much more totalizing than either Fisher or Leigh. He takes the reader through the entire process of making a film, from the origins of the source material to the many unsung heroes vital to production, moving through the 20th century as he does so. The writer-director, Bill Johnson, the film’s star, Wren Lake, and its producer, Al Mac-Teer, are the principle characters, but Hanks makes sure to give page space to the hair and make-up people, the featured extras, the drivers, the first and second and second-second assistant directors, and more. It’s an earnest and authentic ode to the monumental undertaking of cinematic storytelling. It’s also the novelistic equivalent of a nice-guy boss making a big show of knowing everyone’s names and even details about their lives.

The result is that the film being made—a superhero flick entitled Knightshade: The Lathe of Firefall—functions as a kind of protagonist. The narrative drama is less about the personal goals of the characters and more about making the film the best it can be. Unfortunately, the film is much less compelling than the people creating it. Knightshade is a character from Dynamo Comics, a member of the supergroup Agents of Change, who are currently dominating the box office MCU-style with a series of interconnected films. Not much time is spent on the background of any of those characters. Instead, we learn about the history of “The Lathe of Firefall,” a Vietnam War comic about a flamethrower-wielding soldier inspired by the creator’s uncle Bob Falls, a WWII vet who actually wielded a flamethrower, and those old patriotic propaganda comics about HEROES UNDER FIRE and THE MEN WHO WON THE WAR! Hanks’s passion for military history is well known, so the focus on the Firefall aspect of the blockbuster makes sense as the work of the star of Saving Private Ryan and the co-creator of Band of Brothers, but that’s pretty much the only sense it makes.

Firefall isn’t a part of the Dynamo comics on which the Agents of Change franchise of films are based, but rather a one-off—and an uncharacteristic one, at that—from a 70s counterculture outfit called Kool Katz Komix (a nod to Robert Crumb’s Zap Comix) that Dynamo now happens to own. Why Johnson decides to incorporate this random character from outside the Knightshade canon into a tentpole franchise outing is a bit bewildering, especially because nothing about Firefall’s origins makes its way into the final film; it’s just a soldier carrying a flamethrower, essentially borrowing only the look of the character. Not to mention that Firefall is Knightshade’s antagonist, so it’s not like there’s any element of militaristic propaganda. Sure, it’s easy to imagine Hanks wanting readers to juxtapose the heroes of WWII with the superheroes dominating theaters, but otherwise the emphasis on Firefall (we’re given two full comic renderings of Firefall’s previous iterations) is completely inexplicable.

Hanks, then, gets all the aspects of a film shoot correct (he even includes footnotes to explain insider nomenclature) but fails to make the film itself feel like a valuable endeavor.

Parts versus Sum

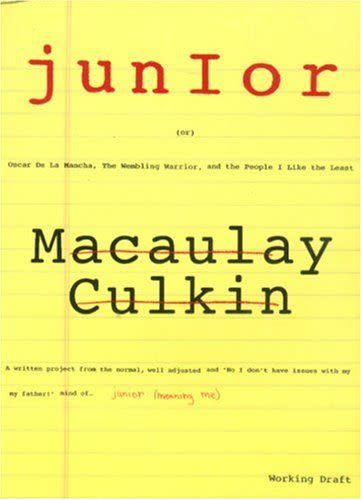

In Macaulay Culkin’s bracingly honest autobiographical novel Junior (the ‘I’ in Junior is capitalized in many places in the book, in case we weren’t clued in to its confessional nature), the narrator says things like, “I am a bag of bones stuck to a very large rock spinning a thousand miles an hour,” and kind of means it. Junior is a freewheeling, diaristic mishmash of self-obsession, score-settling, and trauma recovery, like a therapeutic exercise that somehow got published. At one point, there’s a list of “THE PEOPLE I LIKE THE LEAST,” which includes Dennis Rodman, Hitler, Pete Sampras, Bill Maher, vegans, and “People who attend Limp Bizkit concerts.” But the person Junior hates the most, by a mile, is his dad, to whom the book dedicates a good deal of its space. You get the feeling while reading it that you definitely shouldn’t be reading it.

Anyway, there’s a part where Junior writes, “I am a collection of thoughts and memories and likes and dislikes. I am the things that have happened to me and the sum of everything I’ve ever done.” This view of identity as an accumulated total is often how actors construct their novels. James Franco’s Actors Anonymous, for example, reads much more like a sequence of stories than a novel; not because Franco employs various techniques and styles, but because the disparate sections never cohere into anything singular. Its organization is haphazardness disguised as deliberateness.

$16.00

amazon.com

Even Carrie Fisher’s Postcards from the Edge, while a much better book, ultimately fails to gel together, because it too is structured like short stories with some throughlines. The jacket description of the first edition calls it a “fiction montage.” Today’s marketing parlance would refer to such a work as a novel in stories, which is exactly how Molly Ringwald’s When It Happens to You is described on its cover. Revolving around a marriage in crisis, When It Happens to You explores the effects of a husband’s infidelity on the family and even the community they live in. Ringwald has a deft, precise, and perhaps a bit staid style (she’s also a translator), but some of the plot elements are predictable, and the “novel in stories” structure can sometimes mask issues of completeness. A novel can, of course, be made up of discrete parts, and a novel needn’t feel unified for it to succeed, but an issue that plagues many novels in stories is that because there are so many gaps between the narratives—as these works tend to be nonlinear and polyphonic—readers are constantly reorienting themselves, sometimes paying more attention to figuring out how this story will connect with the others than to being moved by the story.

Hanks, by using the steps of the filmmaking process as his structure, avoids the pitfalls of a novel in stories, but runs into other problems as a result. The linear and episodic nature of The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece means that characters who are vital to an early section will disappear for the majority of the novel’s 400-plus pages, sometimes never reappearing at all. When there are dozens and dozens of named characters appearing and then promptly vanishing, a reader’s investment in the cast spreads too thinly, meaning that the story here is the compelling force and not an emotional connection to the actors. So even though Hanks’s construction is appropriate and accurate to the experience of a movie shoot, it’s less successful as a novelistic foundation.

They Write Parts for Themselves

In my mind, as I read The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece, Tom Hanks played the role of director Bill Johnson. I recognize that this is completely unfair baggage to bring into it, but I also suspect that Hanks has absolutely thought about it too. Not in the forefront of his creativity, exactly, but in there somewhere.

Sometimes the main characters of actors’ novels do seem like parts their authors might want to play. In Krysten Ritter’s engaging 2017 mystery Bonfire, an environmental lawyer returns to her hometown in Indiana to investigate a giant plastics corporation. It’s almost impossible to imagine anyone other than the star of Jessica Jones as the protagonist Abby Williams, whose narration features the same kind of clunky noir-ese as Marvel’s superpowered P.I. A high-school friend brings up the plastics company to Abby, who thinks, “The mention of Optimal is bait—it must be. But this time she’s not the one who gets to stand on dry land and cast.”

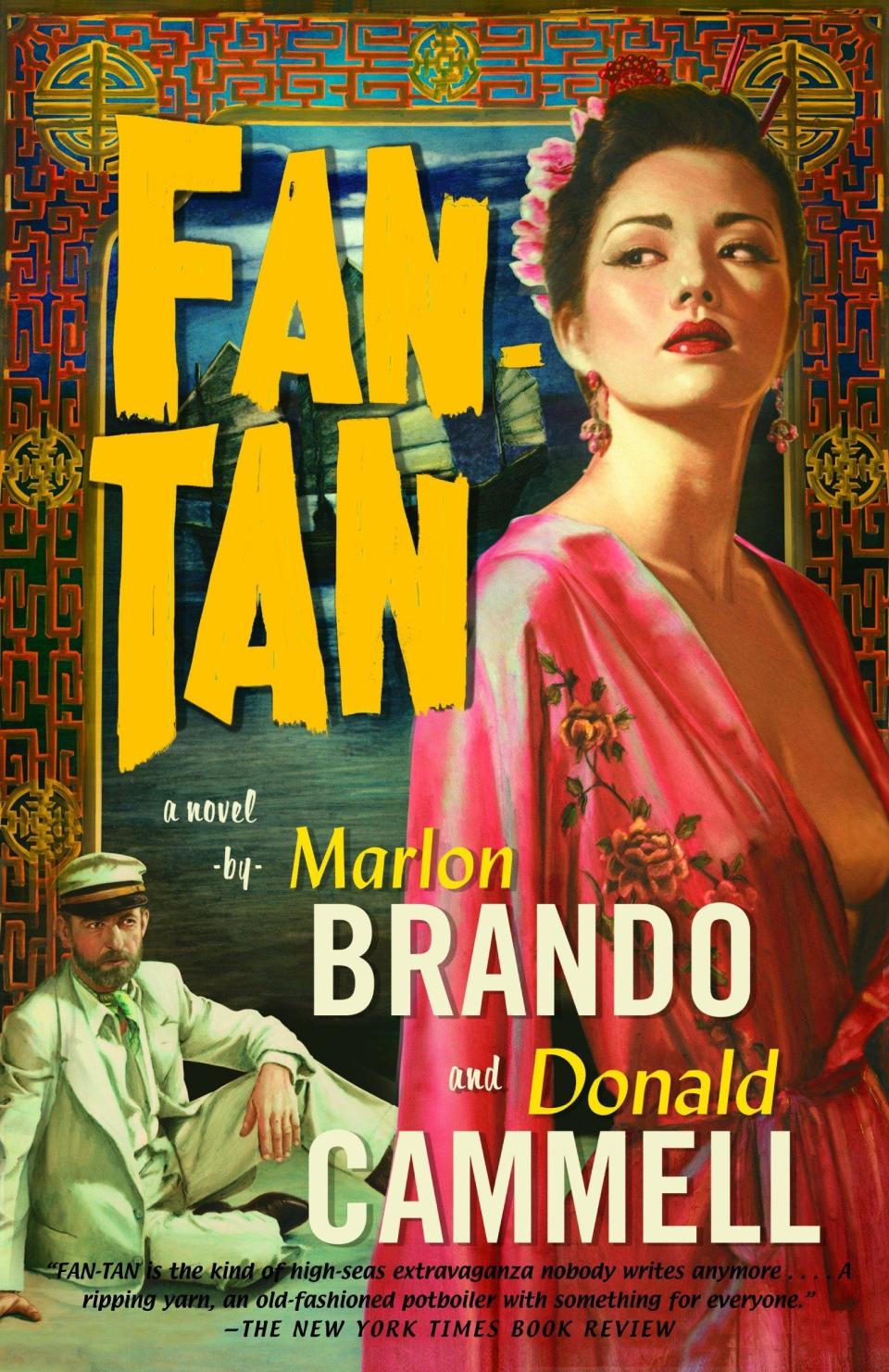

Anatole “Annie” Doultry, the swashbuckling hero of Marlon Brando’s pirate adventure Fan-Tan, originated as a role Brando imagined for himself. Fan-Tan was co-written with Donald Cammell, a troubled figure and notorious libertine who hung out with Mick Jagger. According to Marianne Faithfull, Cammell had “a taste for threesomes”; he began dating his eventual wife China Kong when she was fourteen and he forty. In 1996, he shot himself in front of Kong, who later stated that her presence at his suicide had been the plan all along. As film scholar David Thomson notes, Brando and Cammell collaborated by recording themselves as Brando embodied the character and improvised lines.

$13.95

amazon.com

In case you were looking for some insight into Brando’s self-perception, consider a sex scene near the end of the novel in which Doultry’s “great phallus,” his “leaning tower of piss,” is referred to as a “Scottish caber,” a tree trunk. Not to put too fine a point on it, a young boy spies on them through a keyhole and gasps at the pirate’s “other statue” (the first being his chiseled physique). Madame Lai, a gangster femme fatale, “could not take her eyes off it.” She gives Doultry a blowjob and sticks a black pearl up his ass—the pearl being the MacGuffin of the story, the booty, as it were. This is how—for real—the Brando-esque hero’s orgasm is rendered on the page: “‘Oh, Lord,’ he cried out. ‘I’m a comin!’” Then, there is this curious line: “He came and he came—we are dealing with a hero here.” Who knew that huge loads were so essential to heroism?

Sometimes a character an actor creates in a novel is nothing more than a transparently self-aggrandized self-portrait. I mean, come on, who do you think Kirk Douglas had in mind when he described the protagonist of his novel Dance with the Devil (1990) like this:

Danny Dennison was striking—six feet two, muscular, with a head of thick black curls here and there reflecting steel gray, high cheekbones, intense brown eyes. The eyes could intimidate, make him seem unyielding, especially when, deep in thought, he narrowed them, tensing the muscles of his firmly set jaw. But when he smiled, his face relaxed, creasing with dimples and projecting a disarming boyish charm, though the eyes always stayed just a little sad. With his good looks, he certainly didn’t appear fifty-five, and he was often taken for the star actor, not the director.

And who do you think Douglas pictured as he wrote this scene, in which this sad (but muscular!) and boyish (but intimidating!) fifty-five-year-old casts a twenty-year-old woman in a film he’s making, immediately asks her out for drinks, and has sex with her in a hotel? Douglas was in his seventies (and not to mention, only 5’9) when he wrote Dance with the Devil, but a creepy old man can dream and put it to paper and expect others to read it, right?

Compared to Annie Doultry and Danny Dennison, Hanks’s Bill Johnson is a role Hanks would embody wonderfully. Johnson has a gentle, paternal presence on the set, as he’s an artist genuinely invested in what’s best for the film, not a dictatorial taskmaster or a sexual predator. He is the platonic ideal of a filmmaker: smart, collaborative, considerate, and visionary. Hanks in the role would make Johnson even more of a symbol of cinematic magnanimity, one perhaps more aspirational than truthfully representational, not unlike the way Andrew Shepherd (played by Douglas’s son Michael; sorry for talking shit about your dad, Mike) in The American President speaks to the possibilities of American politics rather than its realities. Hanks is one of the few people in Hollywood who is as good-natured and caring as Johnson, so why cast anyone else?

Hanks loves the picture business, particularly the vast cooperation that must occur for anything to make it onto celluloid, as aptly articulated by one of the characters late in the novel. After someone asks who works the hardest on a film set, the character says, “Everybody works the hardest… At some point, and there’s no telling when that moment is, someone is responsible for the whole movie, right then and there… Everyone on the movie has to do their job well or they become a problem. They have to work hard. And keep their word, too. Everyone has the most important job on the movie.”

The unfortunate irony, however, is that although The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece is Hanks’s ode to the power of movies, it might also inadvertently end up being a kind of eulogy, as much of the cultural capital of films has moved over to television and streaming (which Hanks is keenly aware of; the film being made in the novel is set to premiere on a streamer). If ever an adaptation of The Making of Another Major Motion Picture Masterpiece arrived, it probably wouldn’t be a major motion picture; it would be another prestige limited series masterpiece, which just doesn’t roll off the tongue the same way.

So, Are There Any Great Novels by Actors?

Again: no.

But there are a few interesting, noteworthy, and in one case, a very, very good one that I didn’t get a chance to mention.

Sidney Poitier’s 2005 sci-fi-inflected Montaro Caine is like one of those globe-hopping 90s event films in which disparate characters encounter various mysteries that ultimately interconnect. It’s a fun, tightly constructed thriller interested in big ideas about the universe. Though its message strains credulity by its finale, it’s full of fascinating ideas. It doesn’t entirely work and gets pretty schlocky by the end, but it’s one of the least actorly novels written by an actor.

David Duchovny, who played a novelist in Californication from 2007 to 2014, has published four novels and a novella since 2015 (!), and though he has yet to produce a great novel, his wildly varying books show ambition and range—from the comic inventiveness of Holy Cow to the oddball philosophizing of Miss Subways. Duchovny seems like a likely candidate to craft a true masterpiece… if, that is, he continues to publish. If his roles are any clue, Duchovny’s recent appearance as a literary scholar on Netflix’s The Chair suggests that he’s still invested in the form (or it means his next career move will be toward academia).

The best novel that I’ve read by a Hollywood actor is Steve Martin’s An Object of Beauty, his third. Shopgirl and The Pleasure of My Company, his first two, have some things to recommend them, but are ultimately the work of a writer figuring out how he can make a novel work. With An Object of Beauty—which adds to Martin’s maturing skills his considerable knowledge of and passion for the art world—Martin creates a memorable character in Lacy Yeager and some beautifully melancholy moments. Though he’s published other books since 2010, when An Object of Beauty came out, Martin has yet to produce another novel, which is unfortunate but common. To paraphrase a line from That Thing You Do, spoken and written by Tom Hanks, it’s a common tale. An actor with one, two, maybe three novels max? A very common tale.

Denouement

As I said: the novel is a difficult form. Its practitioners are known for their extreme dedication, their rigid routines, and their idiosyncratic superstitions. Take a brief tour through Mason Curry’s Daily Rituals for evidence: Haruki Murakami gets up at 4:00 A.M. and writes without a break until 9:00 or 10:00 A.M. Anthony Trollope required himself to produce “250 words every quarter of an hour.” Honoré de Balzac went to bed after his 6:00 P.M. dinner, awoke at 1:00 A.M., wrote until 8:00 A.M., napped for an hour and a half, then wrote again from 9:30 to 4:00. Ernest Hemingway was also an early riser, and he also wrote standing up. Marcel Proust chose to “withdraw from society” to compose his monumental work In Search of Lost Time, which he wrote in bed. Truman Capote also wrote while supine, and he possessed all manner of superstitious rites, like the fact that “he couldn’t allow three cigarette butts in the same ashtray at once.”

Writing fiction demands a great deal—time, mental energy, self-discipline—and the rewards are culturally nominal and financially non-existent. No one is accusing these actors of entering into the literary world for cachet. It’s clear for the most part that Hanks and co. genuinely love novels, as writing and publishing them brings them very little that their established careers couldn’t create tenfold. Actor-novelists are not interlopers of literature; they’re merely amateurs. They belong here just as much as anyone.

True literary talent comes mostly from boring, uninspiring, and lonely hard work. There’s a reason writers almost always have an ambivalent relationship to their craft, as it can be both the source and the relief of their existential struggles. It’s not something someone suddenly has or was born with, it’s not something money or privilege can obtain or even accelerate, and it’s not a role you can play. Literature is not a stage; it is a vast, flat plain with scant resources. The only people there are the ones who choose to be, and the ones who don’t fit in anywhere else.

You Might Also Like