How a Grassroots Effort Is Saving One of the Most Important Houses in American History

A version of this story originally appeared in Preservation magazine. Reprinted with permission of the National Trust for Historic Preservation in the United States.

In the late 1930s, when Emily Hutchinson Meggett was a young girl growing up on South Carolina’s Edisto Island, she would often walk the three-quarters of a mile from her family’s house to her granduncle Henry Hutchinson’s property. There, she and her siblings and cousins would play hopscotch or hide-and-seek.

Sometimes they’d pull a vine off a tree and use it as a jump rope. The adults, including Henry’s wife, Rosa, would sit on the house’s big wraparound porch, laughing and talking. The kids weren’t allowed to partake in the adults’ conversation, recalled Meggett, who passed away in April. “Parents back then, they didn’t talk so much in the presence of children,” she said. “You couldn’t sit in their company. When company comes, you better be scarce.”

From that porch, the Hutchinsons could survey their 10 acres of land and the marsh beyond. They raised chickens and hogs and grew fruit and nut trees near the house, but they relied mainly on sea island cotton for their income.

On an adjacent plot, Henry, who had been born into slavery in 1860, operated one of the first Black-owned cotton gins on the island. He prospered by selling the refined product to markets in Charleston, about 45 miles to the northeast, until a boll weevil infestation in the 1920s decimated the island’s crop.

Around 1885, Henry had built the Folk Victorian-style house using his own hands, with help from family members. The house was said to be a wedding gift for Henry’s bride, Rosa Swinton.

The rectangular, four-room, two-story residence, with its side-gable roof and eaves decorated with stylish Victorian detail, was a good home. It stood on four-foot-tall brick piers that spared the house from flooding during storms, such as the infamous Sea Islands Hurricane of 1893, which killed at least 1,000 people. As the tempest picked up, around 50 of the family’s neighbors huddled in the jam-packed house, sharing food, singing spirituals, and praying until the storm passed.

Regally set off from the road like one of the island’s white-owned plantation houses, the Hutchinsons’ home was a stark contrast to the one- and two-room cabins where Henry and others born into slavery had lived. It stood as a testament to the hard work and perseverance of Edisto’s freed people after the Civil War.

Henry died in 1941 and Rosa in 1949. The house was passed down through the Hutchinson line until the 1980s, when it was rented out and ultimately abandoned.

In the years that followed, the strong island winds and sea air were not kind to the dwelling. Its metal roof leaked. Termites and rot took their toll on its pine siding and structural supports. It was in very real danger of collapsing. Meggett would pass by and sometimes wonder whether the fragile structure would still be standing the following day.

In the fall of 2023, John Girault, the newly appointed executive director of the Edisto Island Open Land Trust (EIOLT), a local land preservation group, found himself driving aimlessly around the island, trying to familiarize himself with the lay of the land. About 200 yards off Point of Pines Road, up a packed dirt-and-grass driveway, he spotted a deteriorating red-roofed, green-sided building, draped with wisteria. He stopped his car and got out.

“I thought it was an old barn,” he recalls. “I thought, If I were a photographer or an artist, it’s certainly the kind of place I’d like to capture. So I started asking people questions about it, and of course everyone knew it was the Hutchinson House.”

One of those people was Gretchen Smith, director of the Edisto Island Historic Preservation Society. Smith was a friend of the Hutchinson family, including Myrtle Hutchinson, Henry’s granddaughter, who had grown up in the house and loved it dearly. She had been instrumental in bringing attention to the significance of her ancestral home, securing a place for it on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987, and starting a foundation to help save it.

Myrtle died in 2014 at the age of 97, and her granddaughter Arlene Esteves, who had also become a close friend of Smith’s, died just two years later. Both Myrtle and Arlene wanted desperately to restore the house, but they knew the costs would be prohibitive and the foundation hadn’t raised enough money.

For Smith, the restoration of the Hutchinson House became a personal charge. “I promised Arlene on her deathbed that we would save the house,” she says. “And it matters to me that I keep my word to her.”

Smith teamed up with Girault, whose organization purchased the property in 2016 from Myrtle’s son for $100,000, with the goal of restoring the house as a museum. Along with private donations from more than 300 individuals, the EIOLT received grants from the state and The 1772 Foundation, as well as the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, which provides money to protect and restore significant places of African American achievement and activism.

Before restoration efforts began, a land survey team unearthed more than 50 pieces of broken colonoware, earthen pottery often made by Colonial-era enslaved Africans. It became clear that decades before the Hutchinsons owned the land, it was likely home to an African enslavement camp. Further investigations revealed that the property was probably part of a circa 1683 land grant of some 1,500 acres belonging to Paul Grimball, one of the first English settlers on Edisto Island.

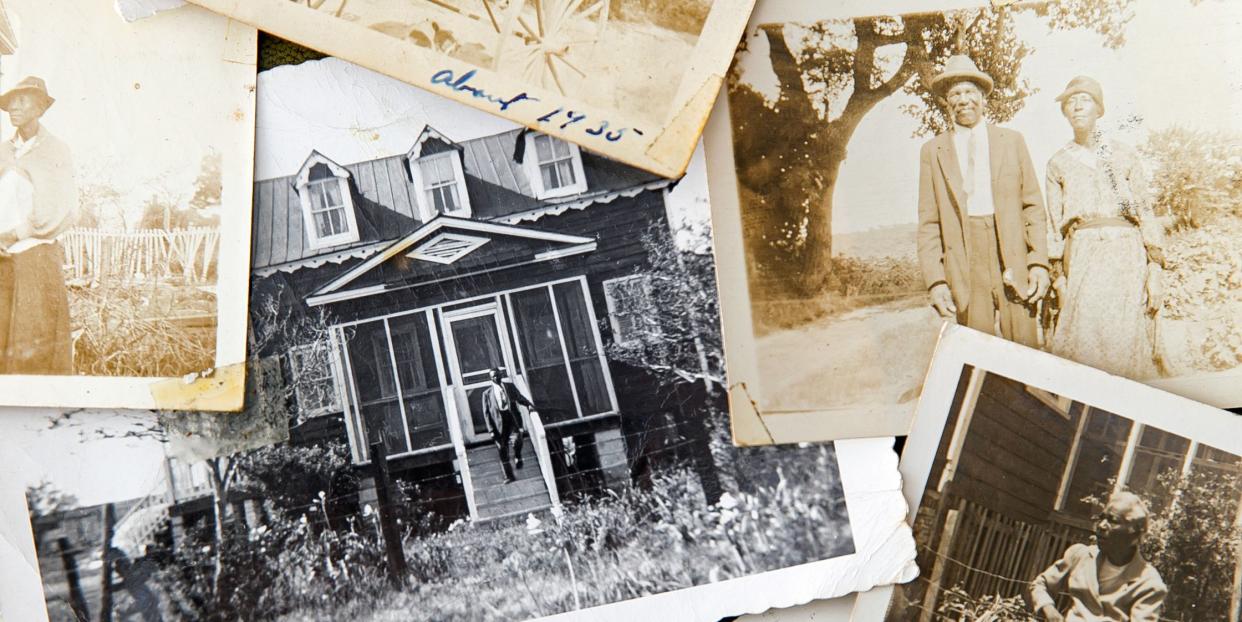

The plan for the house’s restoration, as laid out by architectural firm Simons Young + Associates, was to preserve as much of the building’s original exterior as possible. Numerous modifications had been made over the years, so architects used photographs from the early 1900s to glean its original appearance.

And while the exterior had changed, the interior remained shockingly intact. “That’s the really striking part,” recalls architect Simons Young, remembering the day he first toured the house. “When you walk in it, it’s so well preserved, it throws you back in time. There really wasn’t much that was changed to the core of the house.”

The 368-square-foot first floor contains two rooms and two brick fireplaces, one likely used for cooking at some point in the home’s history. A central staircase leads to the second floor, which contains two bedrooms with sloped ceilings.

After restoration has been completed sometime in 2024, Smith’s organization will provide research assistance for museum exhibits about the Hutchinson family as well as the history of the coastal region’s Gullah Geechee people, enslaved Africans whose descendants continue to share a culture of arts, music, food, and distinctive language.

Like the rest of the Hutchinson family, Myrtle’s granddaughter Gloria Esteves is ecstatic about the rebirth of her ancestral home. But she admits that when she was younger, she didn’t understand why her grandmother was so attached to this decrepit old building.

“There was one point when I asked my grandmother, ‘Why are you trying to save all this?’ She looked at me and said, ‘Girl, I watched my daddy [Henry and Rosa’s son Arthur] work these fields until his hands bled.’

“Even when I talk about it now, it overwhelms me. Sometimes I cry when I tell people that because I understood how much it meant to her. It means there’s Hutchinson blood on this land and there will always be.”

VERANDA Magazine

$18.00

veranda.com

This article was featured in the July/August 2023 issue of VERANDA.

You Might Also Like