The New Age of Grandparenting

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Last December, in one of her first interactions with her newborn grandson, Patty cradled him close, inhaling his sweet smell and marveling at his tiny perfection. The baby, born a few days earlier during a blizzard, was now safely home in suburban New York. Gently, Patty lay her grandson in his crib on his stomach.

“Mom, what are you doing?” her daughter cried, scooping up the baby. “Don’t put him down like that — he’ll smother!

Patty bit her lip. (She also asked to hold her last name, for fear of offending her daughter.) Welcome to today’s world of grandparenting. The Baby Boomers and Gen Xers navigating their roles as family elders face a dramatically different parenting world than the one in which they raised their own kids.

It's a good time to take a deep dive into modern grandparenting. As average lifespans increase, grandparents will be in their grandkids’ lives for longer than ever before. And grandparents say they feel younger and more vibrant than their grandparents before them, meaning their role in their grandkids’ lives is ever-evolving.

Recently, The Good Housekeeping Institute surveyed more than 1,500 people about grandparenthood today, asking them to weigh in on everything from childcare to social media. That survey also included parents, and uncovered a few growing pains in the relationship. Baby Boomer and Gen Xers may feel vibrant and full of wisdom, but their grown kids don’t always see it that way — and many wish grandparents would keep their outdated advice to themselves.

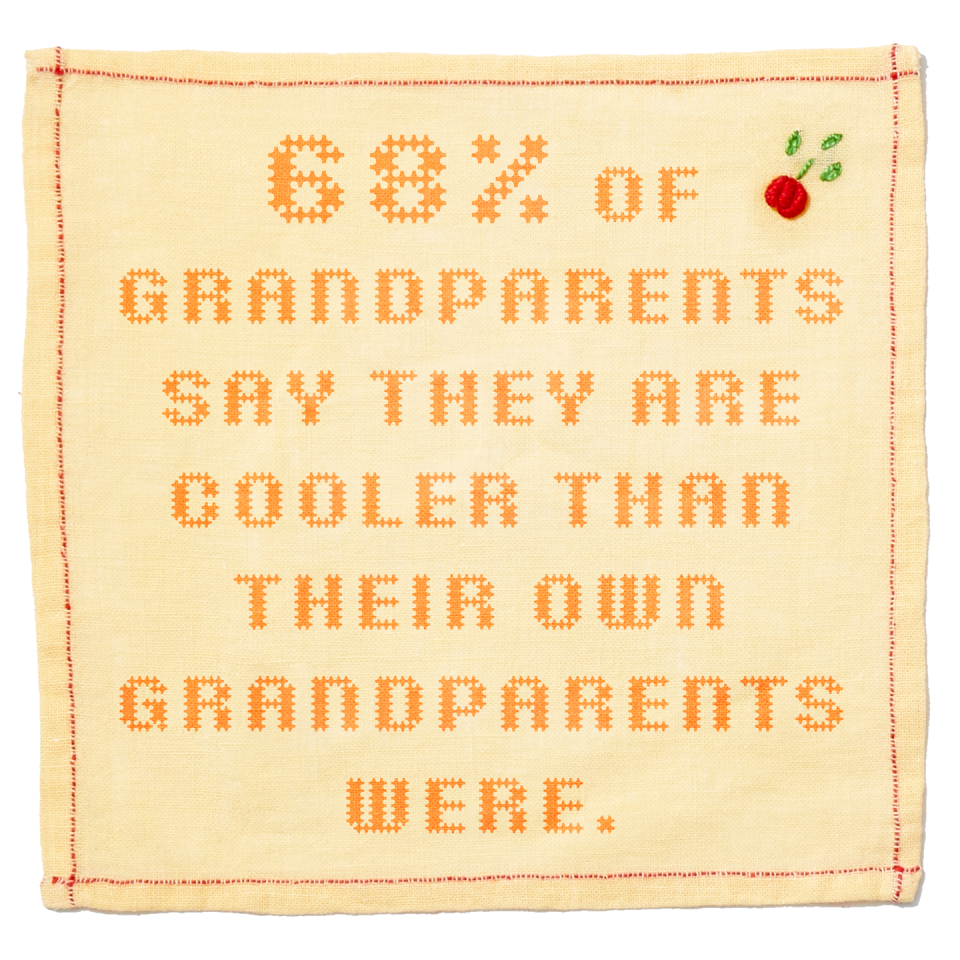

Yet, grandparents don’t think of themselves as old fashioned, stodgy or irrelevant. In fact, they see their generation as adaptable and open to changing times. Our research revealed that 68% of today’s grandparents consider themselves “cooler” than their own grandparents. Certainly, Boomer and Gen X grandparents embrace multiculturalism — an AARP national survey on grandparenting found that a full third have grandchildren of a different race or ethnicity. The vast majority of the AARP survey respondents also say they would fully accept a grandchild who came out as LGBTQ+. In general, they are far more open to gender fluidity than previous generations.

Patty considers herself squarely in that demographic of open-mindedness. After all, she spent “a summer of love” living on a California commune in the 1970s. But when Patty raised her children in the 1980s, the prevailing medical wisdom was that babies should sleep on their stomachs, to prevent them from choking on their own spit-up. Parents today have better information — babies who sleep on their stomachs are at higher risk for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and its safe sleep recommendations.

It’s not just medical understanding that has evolved between generations. Changing demographics and technology has transformed how grandparents relate to and stay connected to their grandchildren. Yet the fundamentals transcend time: Most grandparents see themselves as a source of knowledge and guidance, and provide physical, emotional and financial support. And — like generations before them — they want to be close to their grandchildren. But how involved grandparents are today, and the ways in which they get and stay evolved, is a constantly rebalancing equation.

COVID and Changing Technology

The pandemic upended the grandparenting world. As some grandparents went for more than a year without seeing their grandchildren, “virtual grandparenting” bloomed. By necessity, this cohort has become increasingly adept at technology. Eighty-one percent of grandparents in the GH Institute survey believe that social media and phone calls strengthen their relationship with their grandchildren, and nearly half have increased their use of this type of contact during COVID-19.

Nancy Lee, a social worker who lives in Long Island, New York, describes herself as a “FaceTime babysitter” for her grandchildren in Atlanta and Chicago. Lee reads and does crafts with her younger grandchildren and sends workbooks to the older ones, which they complete online together. She’s also available to step in virtually when needed.

“If the mom has just really had it or the baby is having a moment, my job is to make them feel loved and secure,” she says. “I’ll say, ‘let me have the kids.’”

Paulette Ciotti, a yoga and meditation instructor, hasn’t seen her granddaughters, who live across the country, since 2019. The FaceTime calls from Ava, 11, and Audrey, 7, have been a lifeline, maintaining a level of casual intimacy during the pandemic.

“It’s such a boon to have a direct connection that doesn’t go through their Mom or Dad,” Ciotti says. “Ava will think of something that reminds her of something we did together, and call. Audrey might be bored, and we’ll figure out something for her to do, like, ‘go into the backyard and look for this’ or ‘go into your second dresser drawer and tell me everything that’s in it.’”

Those who live closer to their grandchildren have stepped up their childcare, as they watch their own kids struggle to balance remote work, home-schooling and caregiving. A resounding 90% told the GH Institute that they watch their grandchildren because they want to, with just 10% saying they felt childcare was an obligation.

Jamila Rufaro, a professor who lives in California’s Bay Area, has a photo of her daughter-in-law sitting in front of her home computer, remotely teaching a high school lesson on Of Mice and Men, with 20-month-old Jorell on her lap. Meanwhile Dr. Rufaro herself was teaching remotely at Stanford University’s Business School. Eventually, she juggled her own schedule to babysit Jorell and his 5-year-old sister, Ellora, two days a week.

Some grandparents felt helpless as they watched their far-away kids navigate childcare during the pandemic. Therese Marra, an accounting clerk in Delaware, worries about the stress on her daughter Heather, who lives in upstate New York. Both she and her wife Nicole work full-time and remotely. Marra’s 3-year-old grandson, Max, is on the autism spectrum, and during the pandemic, his pre-school and support services became virtual.

Marra, a grandparent who herself works full-time, wished she could do more to help. She’s told her daughter and daughter-in-law how proud she is of them for figuring out ways to make it all work. And, according to grandparenting experts, that may be the best support of all.

Grandparenting 101 and the Perils of Advice

New mothers, particularly, need reassurance that they are doing a good job and often hear well-intended advice as criticism, say Nancy Sanchez and Marilyn Swarts, who teach a grandparenting class as part of the perinatal education program at Stanford Children's Health in California. Hormones are still elevated, and parents haven’t yet gotten their sea legs. At the same time, grandparents feel marginalized and unneeded if they’re told their guidance is out-of-date or unwelcome. Emotions run high until the new roles are established.

“You remember when you taught your child to ride a bicycle, and you just kind of hung on to the back until they got their balance?” Sanchez, a perinatal health educator and counselor, asks. “That’s all you’re doing as a grandparent. You’re supporting them, helping them get their balance. But it’s their ride. This is their baby.”

Sanchez and Swarts started the class after running support groups for new mothers and hearing the same complaints about grandparents challenging new parents on baby care. A mom committed to breastfeeding, for instance, might be crushed if her mother said, “Give that baby a bottle. She’s hungry.”

If grandparents were more informed about new medical developments and versed in common relationship problems, the nurses reasoned, things would go more smoothly. The class took off, and today, grandparent classes have spread all over the country.

So what happens when parents and grandparents are out of step? Sharon Ralls, a Massachusetts grandmother of six, remembers her own mother’s parenting advice always began with: “If I were you …” Ralls modified her approach concerning her own grandchildren. “Mine is, ‘You might want to consider …’ I give them an option and that’s it.”

Offering guidance or holding your tongue — that is the question. In her class, Sanchez reminds grandparents that they are in a new role — still parenting their child, but not the grandchild. With advice, she says grandparents must take care not to undermine new parents’ shaky confidence. Swarts is more direct: “I call it ‘Zip the lip. Bite the tongue.’”

What’s more, Sanchez and Swarts emphasize that grandparents must respect their kids’ parenting decisions. And many grandparents report doing just that, following parents’ guidelines to the letter.

“Brittany gives me the rules and I don’t deviate from the rules,” says Jodi French, a step-grandmother of two in Maine. “If she says that they have to go to bed at 8 p.m., I put them to bed at 8 p.m.. My mother didn’t respect my parenting style, whereas I respect Brittany’s. She’s an amazing mom.”

Michael McDaniel and Bob Benson have three grandchildren. The grandfathers — called “Daddy Mac” and “Big Papa” by the little ones — are scrupulously deferential. After being corrected, they now say “good job” instead of “good girl” to praise their granddaughter, Julianna. When they wanted to play a game with her, they checked with the parents on rules on winning and losing behavior.

“We ask questions because they raise their kids in a different way than we did,” Benson says. “I just want to make sure we’re careful to navigate how they want their kids to be raised so that we fit into the plan.”

Not all grandparents are as compliant. One grandmother has a sign in her house that says, “What Happens at Grandma’s, Stays at Grandma’s” proudly displayed at her house. “If we want to stay up until midnight and eat candy in bed when she sleeps over, that’s part of the fun of being a grandma,” she says. (But only anonymously.)

Grandparents not respecting rules was one of the biggest complaints from parents in the GH Institute survey. “Some of my children’s grandparents try to undermine my husband’s and my decisions,” one respondent said. “It crossed our boundaries of respect.”

Forging New Families

Multi-racial and multicultural families can also be new territory for grandparents, but they are adapting. The older generation in multiracial families tend to have strong connections to their own cultural roots, says AARP. Almost all (90%) of grandparents believe it’s important that their mixed or different raced grandchildren understand the heritage they share. They also report strong connections to the parent of the other race and with their mixed-race children’s other set of grandparents.

Dr. Rufaro was so fond of the parents of her son’s girlfriend, that she “proposed” to them before the kids were married. “We just had the best time together,” she says. “One day I asked if they wanted to be grandparents with me. They said yes.”

Still, challenges remain. Dr. Rufaro’s son is Black, and her daughter-in-law is white. When Dr. Rufaro was shopping with her granddaughter Ellora, a woman asked how much she charged. “I said, ‘Oh, no. I don’t charge. I’m the grandmother.’ And then she said, ‘You know, you don’t look like her.’”

For Nancy Lee, the differences are cultural. She is Chinese, and her two sons both married women who are Korean. She refers to them as her “daughters-in-love,” and she loves how they bring new food and customs to the family. Swarts says that in her grandparenting class, concerns often come up about what cultural traditions will be passed on.

Swarts advises parents to decide together which customs they will honor and maintain, and then present a united front to grandparents. (She also advises to let the child of the concerned parent — not the in-law — do the talking.) If a grandparent is really worried about some aspect of baby care — co-sleeping, breastfeeding and so on — Swarts suggests that grandparents accompany parents on a pediatric visit. “This generation tends to respect authority, like the baby’s doctor,” she says.

The Rules Have Changed

Grandparents have a lot to learn to keep up with the evolutions in child rearing. Starting from the first weeks of conception, today’s parents have far more information at their fingertips. While Boomers and Gen X grandparents may have relied on one or two books, now parents are constantly online.

“Kate practically had her medical degree in obstetrics,” Margaret Atkinson, a realtor in Florida, says of her pregnant daughter, who educated herself about all things pregnancy online. “Like, ‘this week he can open and close his hands and curl his toes.’ There’s so much more knowledge.” Websites like The Bump and BabyCenter, which weren’t around in the Baby Boomer/Gen X days, allow expectant parents to follow their baby’s development week by week in detail.

Standards of infant care have evolved, too, sometimes to the consternation of the older generation. One grandmother described swaddling as “a baby straight jacket,” while another marveled, “they wrap them like tiny mummies,” even though the AAP says swaddling can help with baby sleep when done correctly. One grandfather speculated that today’s baby car seats “must’ve been designed by NASA” and wondered why the restraints “didn’t leave scars.” Cribs are kept bare now except for a crib sheet (to prevent SIDS) so the bumpers or baby blankets grandmas saved are not welcome gifts.

Grandparents are bemused at the amount of equipment (“Diaper wipe heaters?”) the number of playthings, (“the house is like a toy store”) and find the way parents constantly “stimulate and entertain their children” troubling.

“I remember saying to my kids, ‘I don’t want to hear or see you until tomorrow morning,’” says one grandmother. “I don’t think I was a mean mother, but we sure were stricter.”

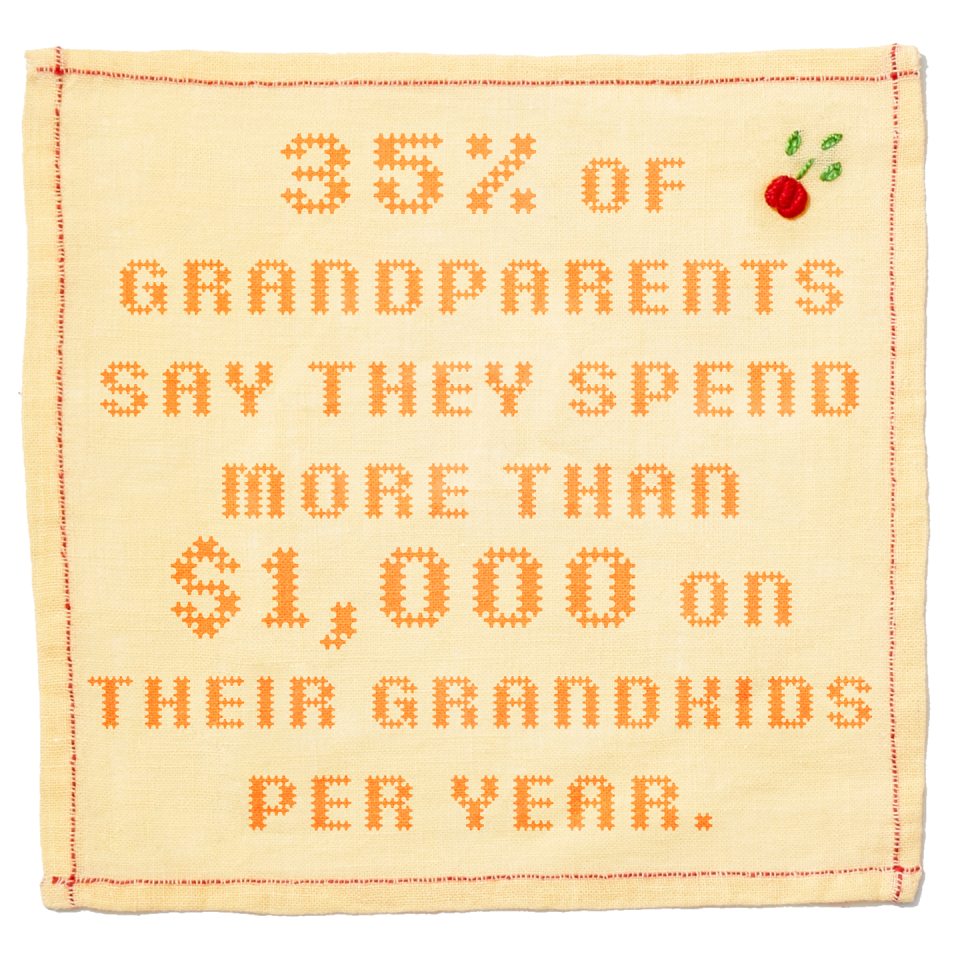

According to both the GH Institute survey and the AARP study, grandparents wish that parents were firmer, particularly when it comes to manners, respect and learning the value of money. Grandparents are baffled by the “democratization” of the household, where kids are given a large say in decisions. And they worry that their grandchildren don’t know how to play outside in an unstructured way or solve problems without looking at their phones.

As much as this generation of grandparents appreciates the technology that keeps them connected to their grandchildren, they also worry about the impact of all these electronics on children.

“I try to pull the younger ones away from their technology and then it’s together time,” Ralls, an assistant principal at an elementary school, says. “It’s either ‘Chutes and Ladders’ or dominos or making cards or cooking in the kitchen. It’s those times I really feel like a grandmother.”

Fighting against the ubiquity of technology can seem like a losing battle. Referring to her grandchildren, Liza Waters, a retired teacher says, “the parents are attached to their own phones nonstop. So all the grandkids know how to swipe. The little ones will pick up anything that’s a rectangle and pretend it’s a phone.”

Social media is another new area to negotiate. Some parents post pictures of their baby’s every yawn and smile — and 12% of grandparents in the GH Institute survey thought parents posted too much on social media. On the other hand, sometimes proud grandparents are, of course, eager to share photos, and it’s the parents who worry about privacy and don’t want their child’s image online. “My mother-in-law posts photos of my children on social media without asking permission,” one respondent told the GH Institute. “I find this dangerous as we are foster parents, and she disregards the rules we have in place.” Every family is different, and the general wisdom is that parents set the social media rules, and grandparents follow them. How this actually plays out in practice, though, is often much messier.

Boomer and Gen X grandparents are also surprised by how deeply involved parents are in the minutia of their children’s lives. They don’t remember so closely monitoring their own children’s sleep, food or social life. One used the expression “snowplow parenting” — to describe parents trying to remove every obstacle in front of their kids.

The biggest change since they raised kids is the involvement of fathers, grandparents say. Baby Boomers barely had maternity leave and paternity leave didn’t exist. The pandemic has heightened what grandparents see as a healthy partnership, versus the days when mothers had primary care of the children. Waters’ son recently took family leave and will be the primary caretaker in Massachusetts when his wife works towards her graduate degree in New York. “That’s the cool thing. Dads are way more involved,” she says. “My husband was involved but nothing like these guys.”

“I’m Much Younger Than My Grandparents Were!”

Today’s grandparents remember their own grandparents fondly, but almost as if viewing a sepia photo. As they remember it, grandparents were more sedentary and children “were to be seen and not heard.” The generational differences seemed stark. Grandpas didn’t talk to kids much. In immigrant families, many grandparents didn’t speak English. Black grandparents who were part of the Great Migration brought their experience of Jim Crow with them, cautioning their grandkids to keep their eyes cast down.

Overall, Gen X and Boomer grandparents consider themselves far more energetic than the “old” people they remember. “My grandparents felt ancient,” says French, a CrossFit enthusiast. “You couldn't even talk to them. I mean, I loved them, but they would never get down on the floor and play with us.” Jodi describes herself as “super active” with her step-grandchildren, who are 4 and 18 months.

Grandparents may “feel" younger these days — but technically they’re not. The average age of becoming a first-time grandparent has been climbing, primarily because women are having babies later. By age 65, 96% of people in the US will be grandparents, according to AARP. And with longevity increasing, an estimated 70% of 8-year-olds will have a living great grandparent by 2030.

Alison Bryant, who heads the research division at AARP, says today's cohort of older people are redefining aging. Many 65-year-olds are still in the workforce. They stay more active. And as a group, they tend to be more flexible.

“This generation — and I mean Boomers but also going down to X-ers — they’re pretty good with change,” Bryant says. “They switch jobs more in their lives. They’ve moved around more than generations past. The idea of ‘I can go through phases’ is more ingrained in their personalities and their psyches.”

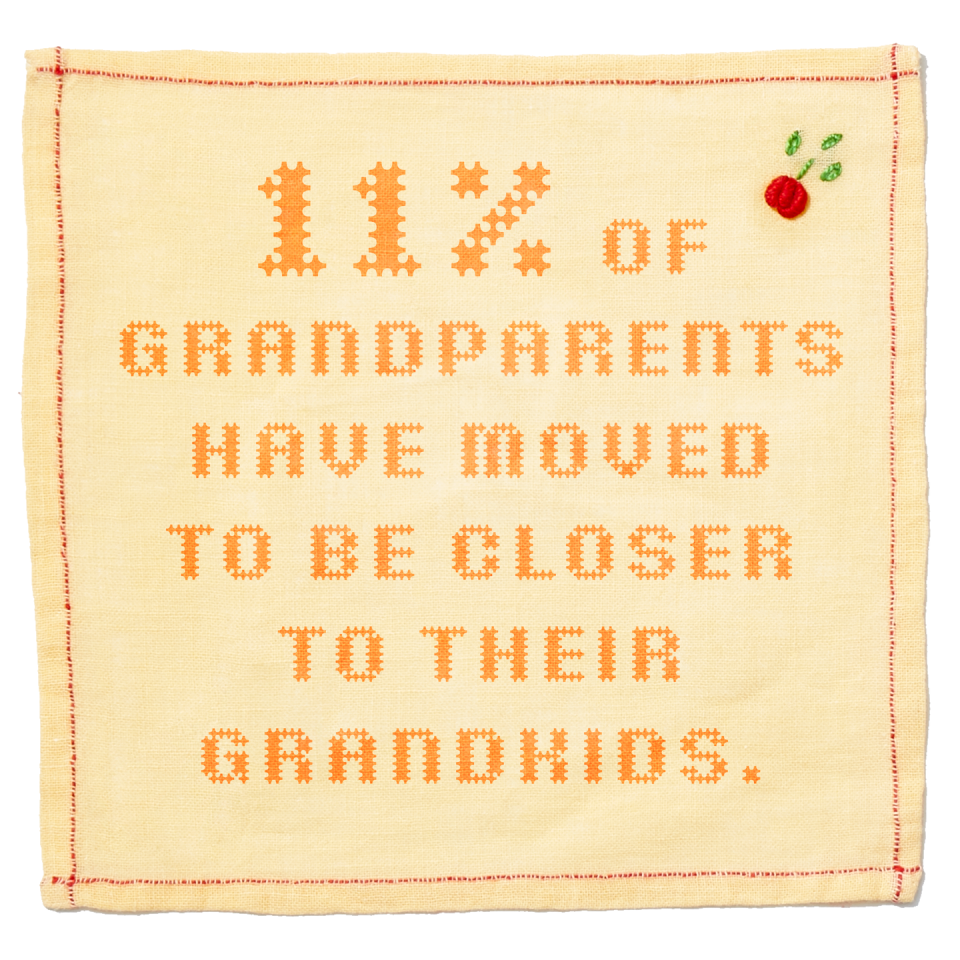

Research shows that after the economic downturn of 2008, many families moved closer to each other, either for grandparents to help take care of grandkids, or for the younger generation to help care for the older.

“We have multi-generational households where Great Grandma may still be alive. So, are you going to be called ‘grandma,’ or something else?” Bryant asks. Only 63% of Boomer grandparents want to be called by traditional names like “grandma” or “grandmother,” and the rest opt for names that “reflect their personality, playfulness or rebellious spirit,” according to the AARP.

Another growing trend is grandparents raising their grandchildren. Almost 7.8 million children under 18 live in multi-generational homes, and more than 2.5 million grandparents are solely responsible for them. Experts point to multiple causes, which include the opioid epidemic as well as high rates of incarceration. Sometimes, parents are struggling with housing issues or mental health problems and grandparents step in.

Ralls and her husband have two grandchildren living with them now, but sometimes they have more. Her son, she says, is “sometimes more friend than father” and the two mothers of her grandchildren have struggled with the responsibility of parenthood.

During a video chat from home, 4-year-old VéRity, one of Ralls’ granddaughters, sleepily climbed into her lap. Later, VéRity would be singing in her virtual preschool and Ralls would don earphones so she could work remotely. The situation with her grandchildren's parents pains Ralls, and she turns to her faith for sustenance.

“We’re the ones who provide structure and consistency,” she says. “There are times when I have to go into my closet and cry. And then I say, ‘Okay, this is the way it is. I’ll find the strength to handle this and keep going.”

Grandparenting: It's Good for Your Health!

The good news is that grandparenting is good for your physical, cognitive and emotional health. The AARP calls grandkids “the elixir of life,” and their study determined that the greater the emotional support grandparents and grandchildren receive from one another, the better their psychological and physiological health.

“There’s a kind of magic about having those moments with these tiny human beings who are part of me and yet their own stunning individuals,” Dr. Rufaro says.

While they sometimes struggle to keep up, today’s grandmas and grandpas love their roles.

“There are a lot of grandparents now being faced with stark realities that are different from what they had thought the world would look like,” Bryant, the AARP researcher says. “But in the end, love triumphs.”

"Good Vibes" cross-stitch pattern by ThreadorDeadClub; "Best Grandma Ever" cross-stitch pattern by ZindagiDesigns and "I'm an Old-Fashioned Lady" cross-stitch pattern by DirtyLittleStitchUS. Prop Styling by Alex Mata.

You Might Also Like