What should we do with Grandma’s old clock?

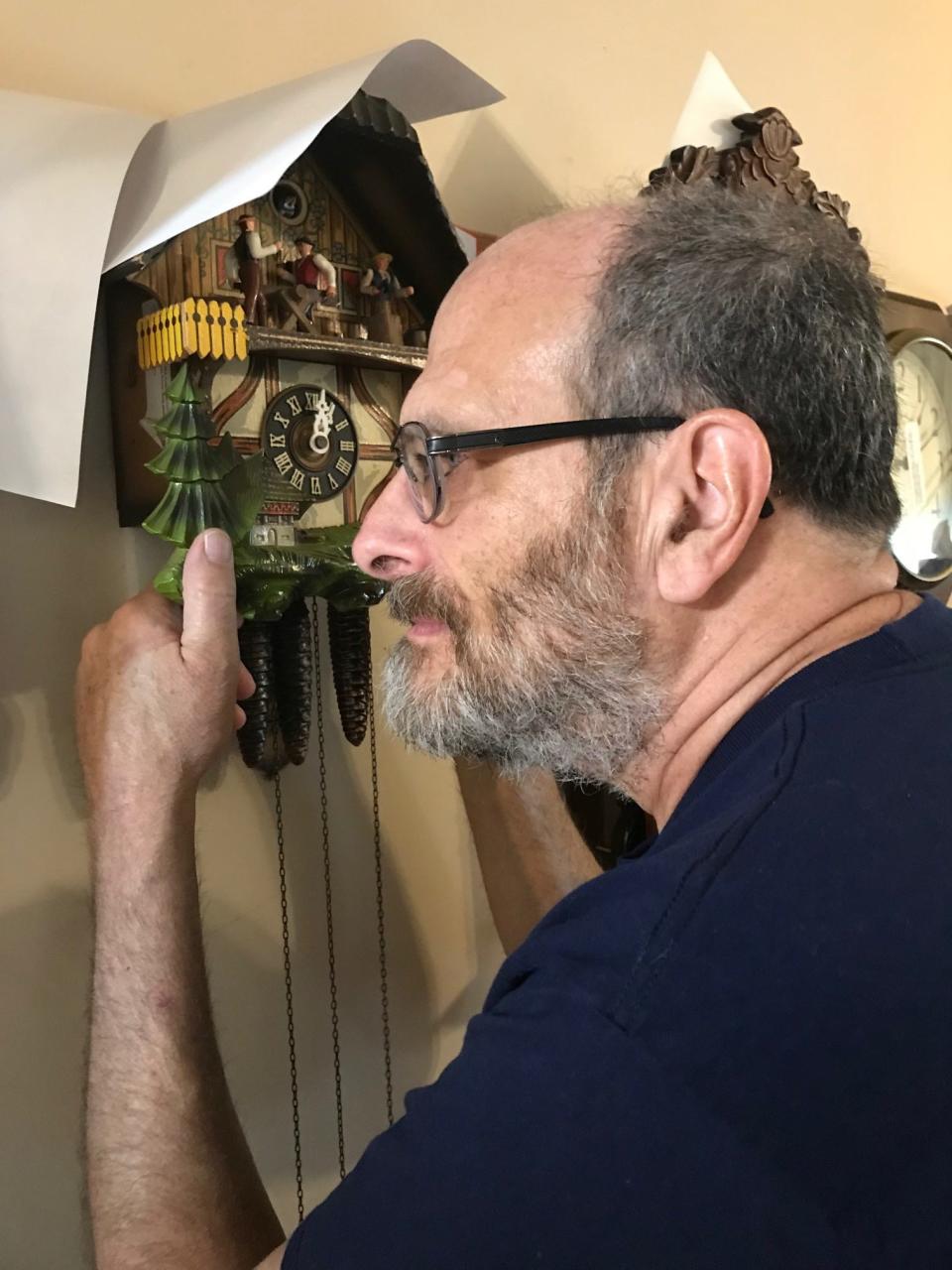

I still repair antique clocks.

I regret to say that I’ve been fixing most of these clocks for several years, for they were brought in during the two years that I was sick, perhaps with “Long Covid®” or perhaps with another, more exotic malady that flattens out one’s wits. Except for an eternal horrid taste in my mouth and the loss of my ability to touch type I survived, but clock repair was another matter.

Antique clock repair involves a few tricks and a couple of special tools, but in general it’s fairly easy work—maybe about the same level as bicycle repair. That said, a year ago I was almost successful in assembling the movement of a 1900 Seth Thomas mantel clock. The holes for the gear shafts didn’t seem to line up properly, and that’s because I was assembling it inside-out. Eventually, my health improved, and after a period of re-education my subsequent work now seems satisfactory.

It’s a bit unfortunate, for antique clock repair is pretty much doomed as a business or even a pastime. That’s because young people don’t like old clocks. They have pendulums to regulate the time and must thus operate undisturbed, so you can’t move them around whenever Madame wishes to re-arrange the furniture. In addition, they must be wound every week or they stop. And they ring out the time every half hour, or every fifteen minutes, whether you want them to or not. And there’s no volume control. And they tick, sometimes loudly.

At one time every family had such a clock in the living room. I grew up with a mantel clock that my father would, with some ceremony, wind each Sunday. [Because life occasionally interfered with that schedule, clocks were designed to run for eight days on one winding.] We were accustomed to hearing it strike the hour, and nobody ever moved it.

But furniture merchants and antique dealers know that young families circa Stardate 2024 use their cell phones to tell time. Some can’t read a clock with hands. The ticking and the chiming and the weekly winding aren’t so attractive, either.

I think there is a psychological aspect as well. For reasons I’d care to not investigate, the writers and artists of scary children’s literature like to include an evil clock in their stories. In cartoons, the hands of a haunted grandfather clock reach out to capture the innocent little mice, and a casual search of kids’ books will yield a substantial crop of unpleasant timepieces.

This is not an ideal way to build a consumer base. One alternative strategy is to remove the old wind-up movement from great-grandma’s wooden clock case and replace it with an electronic, battery-powered movement. No old-time repairman likes doing this, but unless tastes change, it’s apparently what the future holds.

Natalie, whose steady hands have helped assemble many a clock, has heard all this for years. She says that she will still love me anyway.

Mark Kinsler, kinsler33@gmail.com, lives in Lancaster with Natalie and two custodial cats. Both of us now test negative for Covid, hooray, and the cats never worried about it.

This article originally appeared on Lancaster Eagle-Gazette: Kinsler: What should we do with Grandma’s old clock?