When We Split Household Duties, Everyone Wins. So Why Won’t We Do It?

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Surely, more than two decades into the 21st century, we don’t need another deep dive into household equality. Surely, after the 19th amendment, the fight for equal pay, the recognition of “mental load” and all the rest, we have reached a point in American society where men and women, as well as partners of the same sex, can work, earn, parent and plan shoulder to shoulder with little complaint.

Sadly, despite all the progress, we haven’t quite gotten there. In fact, in 2023 one of the most common household dynamics is what academics call “neo-traditional.” This describes a household in which both partners earn income but one person (typically, but not always, the woman in different-sex relationships) does two-thirds of the household work. And the person doing more also likely shoulders the vast majority of the home’s cognitive labor, a.k.a. “mental load.” And though we know same-sex and queer couples tend to have more equitable relationships than do different-sex couples, our social gender norms are so pervasive that even those couples often fall into the “one does more and one does less” dynamic.

That’s what inequality looks like. But what does equality look like, and how close are we to reaching it?

I offer the definition that household equality is when both partners truly split the physical, cognitive and caregiving work, when both people have equal time for paid work, housework and free time. They split the ownership of all household work: the every-day tasks, the sometimes tasks, the financial duties, the child care. No one is “helping” their partner. No one is “managing” their spouse. No one is “babysitting” their children.

I am not suggesting that each task is split 50/50. We all have our areas of expertise or preference: Perhaps one does the laundry and the other does the grocery shopping. Nor am I suggesting an exact 50/50 split every day; that isn’t how partnership works. We constantly alter our behavior to react to our current context — sometimes one of us has to pull back at home to care for an aging family member; sometimes one of us does less at home to push through a big work project.

But from 10,000 feet, over the course of a relationship, you should both know deep down that you each have done your fair share. That's what equality looks like.

Why are we talking about this? Why is it so important to establish a shared definition of equality? Because the research tells us that this imbalance isn’t working for anyone. Sure, it might be more obvious why this is hard for the person-doing-more. But it is also harmful for the person-doing-less. In the end, we all suffer.

We have all collected anecdotes about how various households navigated the pandemic. Some couples we know seemed to find greater equity in their relationships; some did not. These individual stories are powerful, but are they indicative of a trend? Broadly speaking, where are we now? Was there any sustainable change? In 2023, are we any closer to household equality than we were before the pandemic?

I called Richard Petts, a Ball State University sociology professor whose research focuses on family inequalities. Petts has been part of a group of academics following opposite-sex couples through the pandemic, and they have some of the most compelling data to date. (Note: This group recently added same-sex couples to their sample set.)

Among the couples in Petts’s data set, gender equity dynamics for the majority of participants (about 65%) did not change; whatever they were doing in the home in 2019 continued during and after the pandemic. About 15% of the couples initially shifted to be more egalitarian early on, but when things opened up again they fell back into old patterns.

But about 20% of the couples in Petts’s study found more equity in the home during the pandemic — and stuck with it. They did not necessarily get to 50/50, but they moved farther along the continuum of equity.

I asked what characteristics, if any, set that 20% apart from the others. “The strongest predictor across the board was men’s ability to work from home,” Petts explained. “And the second was if moms continued to participate in the labor force. In the grand scheme of things, this shouldn’t be all that surprising. Getting moms into the labor force and getting dads more time at home are the key components, and that manifested during the pandemic.”

One could absolutely see this as a glass half empty. But I also think you could look at it the opposite way, because at least we saw some shift toward greater equality. Twenty percent is better than nothing. And that means that generally, while the average woman continues to do more than the average man, men are doing more in the home in 2023 than they were in 2019.

All the research I have seen from the pandemic has reinforced what we already knew to be true — America continues to have inequitable households. We are still nowhere near household equality. But we are slowly, little bit by little bit, getting there.

Liz Krieger and Gemma Hartley explore this idea of “We’ve made progress – but not enough” in greater detail. “For Some Families, COVID-19 Was the Perfect Household Shake-Up” highlights the feel-good stories from households that found greater equality during the pandemic. “The Wobbly Work of Finding Relationship Balance,” however, notes the many ways we’re falling short of parity and how hard we need to work to continue making progress.

The negative consequences for the person-doing-more are obvious: higher stress, poorer emotional health, resentment toward their spouse, tremendous pressure and anxiety from carrying the weight of the household responsibility and not being able to achieve professional and/or income-earning aspirations.

But what we don’t talk about enough is that this neo-traditional dynamic also isn’t working for the person-doing-less: valued only for income-earning, dissuaded from caregiving, facing impediments to establishing emotional connections with family. This also leads to loneliness, stress and depression — lack of emotional bonds often manifests as poor emotional and physical health for men.

Simply put, inequality is bad for everyone, and equality is good for everyone. When women do less household work, it is no surprise that women have less stress. But what is also important is that when women do less household work, their male partners have less stress too. Greater equality in the home leads to stronger teams: less resentment, more respect, better communication and ownership of shared responsibilities.

While doing research for Equal Partners: Improving Gender Equality at Home, I interviewed men who have an equitable household dynamic, and I asked them, “What is your motivation?” Their answers were all very similar: I am not giving anything up by doing more in the home. The emotional rewards are far greater than the time spent doing not-so-fun chores. I have a better relationship with my spouse. I have stronger relationships with my kids. I enjoy caregiving. I am proud of my contributions to my family. I wouldn’t want to live any other way.

Marisa LaScala’s “Why Won’t the Myth of the ‘Primary’ Parent Just Disappear Already?” explores this idea in greater depth. As long as we have the mindset of an alpha parent, we’re unlikely to move closer to equality.

A more equitable future requires structural changes and social changes. The structural changes are harder to achieve, but not impossible. We need paid caregiving leave for people of all genders, and we need affordable child care so no one is forced to leave work because they have a child.

But while lawmakers and advocates are working on policies, there are some things each of us can do in our everyday lives.

We need to be intentional. Household inequity is not getting better naturally. We’ve plateaued at participation levels — that two-thirds vs. one-third split has been steady since the mid-’80s. We had a global pandemic that forced us into our homes for months — and that brought about change in only 20% of the sampled couples. Researchers estimate that at the current rate, we won’t reach true equity for anywhere between 75 and 164 years. If we want to change that projection, we need to make some intentional choices.

We need to talk about how equality is better for everyone — not just women and girls. The narrative can no longer be that gender equality benefits women and girls. Our new mantra is that gender equality benefits people of all genders, including men and boys, who suffer when they’re put in the Man Box and forced to live up to traditional expectations of masculinity. We are just starting to collect information on how men benefit from caregiving roles — for example, the University of Southern California recently published exciting information about the neurological changes dads experience during caregiving for infants. We need to amplify this conversation and bring attention to the myriad ways we all benefit from equity.

We need to be ready for discomfort. As Petts told me, “The pull of gender norms [is real]. There’s a lot of pressure to be an involved and intensive mother. And that pressure mounts when you work, because the expectation is you’re not as good of a mom if you’re focused on your career, whereas for men it is the opposite: There is much more pressure to be involved in their careers, so it is easier for men to disregard domestic labor, because cutting back on hours is somehow emasculating. These overall gender norms and worker norms are so intense, it is hard to let go of these roles where society sees this.”

I’ll even be a bit more direct. The gender norms we all grew up with are powerful, they’re not going away naturally and they very often subconsciously influence the decisions we make. Being more equitable in the home means we have to intentionally push back on these norms — and that is going to be uncomfortable for everyone involved. And it can be just as hard for the person-doing-more to pull back as it is for the person-doing-less to step up.

I find that people generally think we are more equal than we are; our perception does not always align with our reality. We see women working and think, They must be doing less at home. We see a man grocery shopping with his kids on a weekend and think, Look how far we’ve come!

It is true — we are doing much better than generations past. Compared with our parents and grandparents, we are making progress. But 2023 is a milestone, not an endpoint. We still have much further to go. ⭑

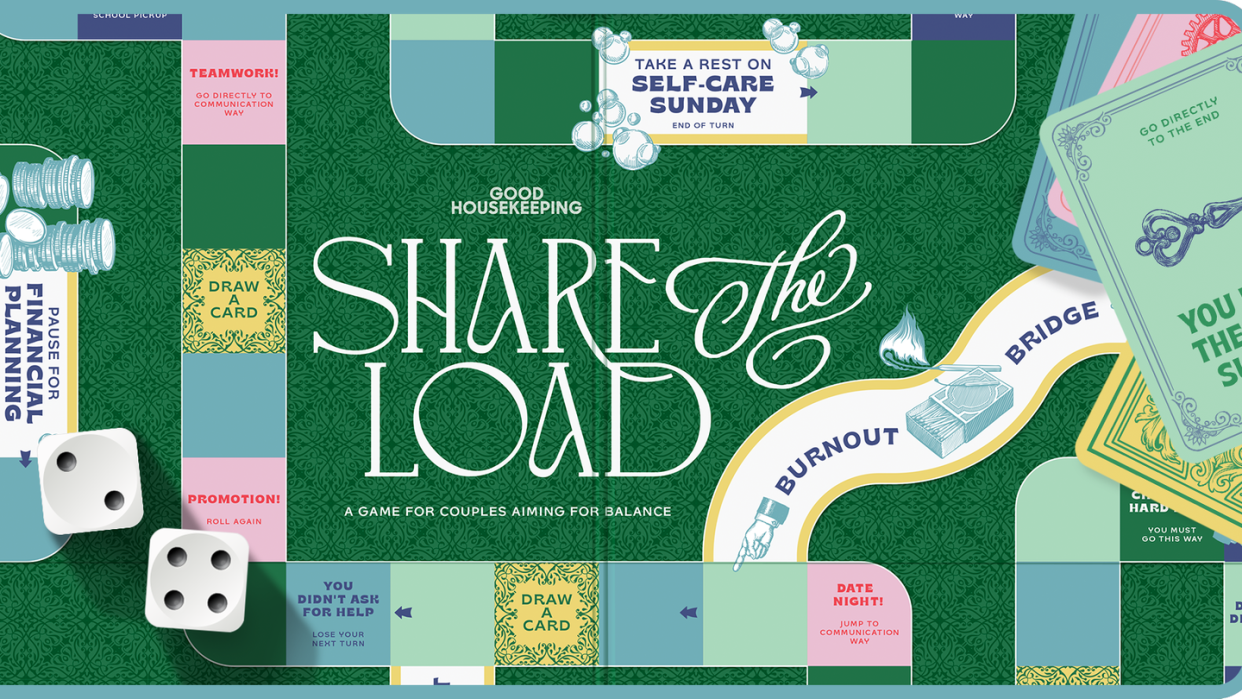

Photographs: Mike Garten. Prop styling: Alex Mata. Design: Betsy Farrell. Illustrations: Getty Images (hands, soap bubbles, matchbox, dice, board pattern and card pattern illustrations); Adobe Stock Photo (all other illustrations, 17).

You Might Also Like