Glynnis MacNicol’s No One Tells You This Puts a Happy Single Woman at the Center

Glynnis MacNicol’s new book presents itself as the antidote to marriage-plot-driven work. “If a story doesn’t end with marriage or a child,” asks the front-flap copy, “then what?” This is a too-simple formulation for MacNicol’s memoir, though. Yes, she watches as her friends from wild nights past settle into domestic torpor in Brooklyn’s less accessible reaches. But it is also a book about what David Brooks once called the odyssey years, that drawn-out phase of finding oneself that stretches far into adulthood—and what happens when those years butt up against one’s parents’ twilight years. (And in MacNicol’s case, her mother’s Parkinson’s disease.) It’s also way less serious and heady than this makes it sound and just a really fun read. I spoke with MacNicol about the process of writing the book and why furs are the best defense against a wintertime bike commute.

There’s a lot of discussion of lipstick and furs in this book. First, how many fur coats do you own? But more seriously, how do you think about the relationship between looking good and feeling crummy? Or looking good and feeling good?

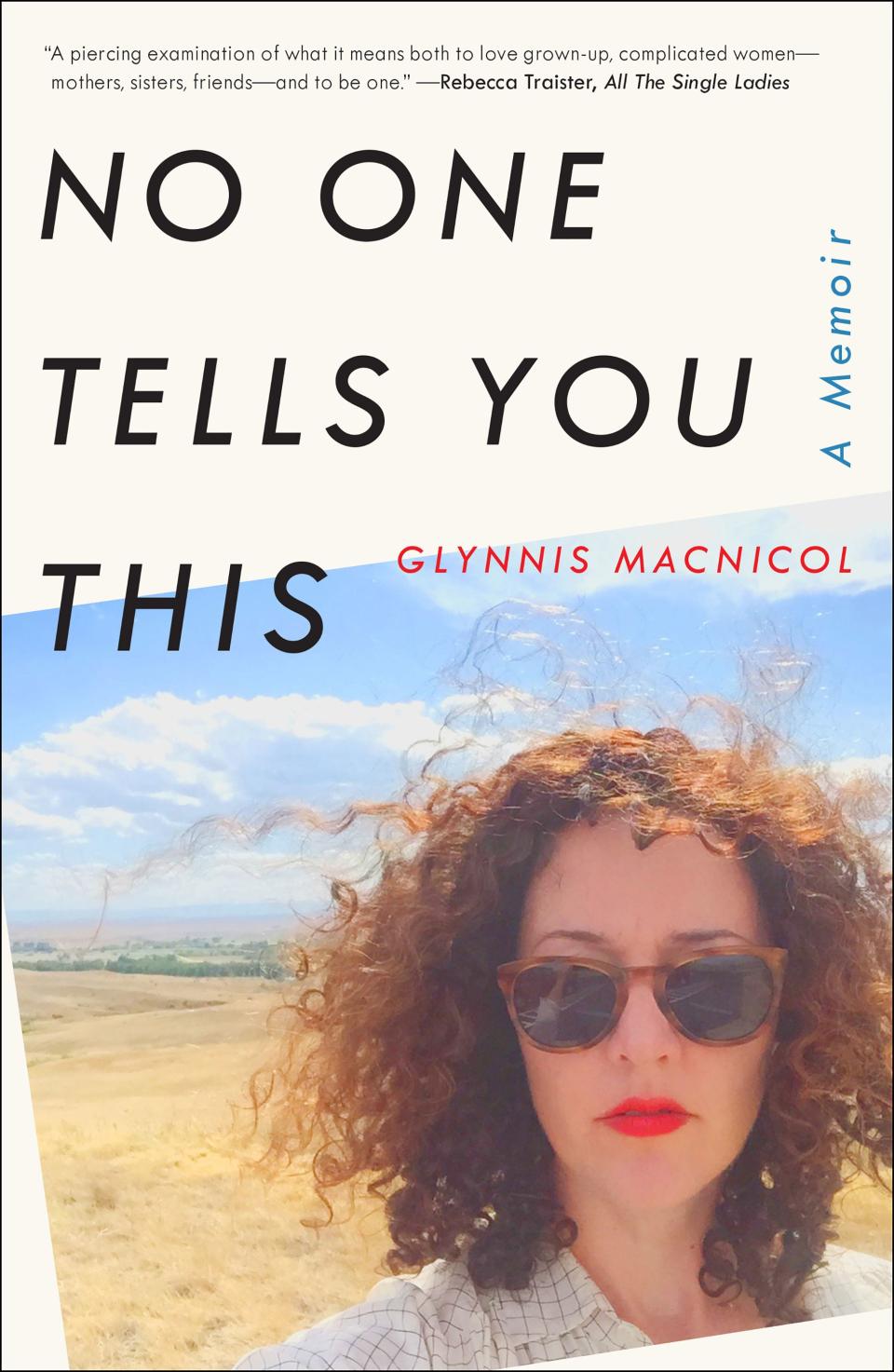

A friend who read an earlier draft also remarked on the repeated appearance of silk pajamas! I don’t think I was conscious of mentioning any of it, but apparently they come up a lot. I own a number of vintage fur coats, some inherited (fur was a real investment for people before it became mass produced, and the names of the original owners are often embroidered into the lining, which I love). But red lipstick is my real weakness. I had 23 at last count. There were a lot of lengthy discussions with Simon & Schuster about getting the color right on the cover. They nailed the final version, but the color on my galleys was so alarming to me I painted over a bunch with Chanel nail polish (Coquelicot) before I sent them to people. I think the connection between all three of these so-called fashion obsessions is that I like a bit of glamour (The Thin Man’s Nora Charles is one of my great fashion loves), however I also ride my bike or walk nearly everywhere, so whatever I wear needs to be easy and functional. I own two pairs of heels, both more than a decade old, because they’ve received so little wear. I also own quite a few caftans for this very reason . . . comfort first always. And an excessive amount of Dieppa Restrepo flats, which stand up to multiple resolings.

I’ve loved clothing, vintage in particular, since I was young and always considered the act of dressing to simply be one more way to express yourself to the world. It’s a mode of expression I enjoy. And it’s often less about feeling good per se than feeling strong. Generally speaking, my outfits always align with how I’m feeling that day, and if they don’t, I’m aware of it and it throws me off. There is also a larger discussion to be had about the difference between style, which I think has very much to do with a person knowing herself well, and fashion, which is so often the experience of having the world tell you how they think you should look. The latter is frequently used to punish women who don’t fit certain expectations about how we think women should look and comport themselves, and I have very little interest in it. I think of Marlene Dietrich’s quote from this charming book she wrote called ABC, in which she came up with a word and definition for every letter: “Glamour: The which I would like to know the meaning of.” The meaning for me is that every woman should be enjoying herself, including not thinking about clothes at all if you don’t want to.

This is a book that bills itself as a chronicle of your 40th year—a year in which many people relied on you to get them through life-changing events. You were busy! And yet it reads like you wrote it in real time. How did you think about the timeline for this book? Did you write it as you were experiencing these things?

I did not write it as I was experiencing it. Which probably speaks to how much I had going on. I’ve kept a fairly regular journal since I was 6 and read the Little House on the Prarie books and decided to write my own version. And yet I don’t have a single journal entry from that year. It didn’t actually occur to me there was a story in it till the year was almost over. I’d turned 40, promptly discovered it was nothing like what I’d been led to believe, and proceeded to spend much of the year complaining to anyone who would listen (including my editors!) how frustrating it was that there were no good stories about single women that didn’t end in marriage or a baby, and definitely none about women “of a certain age.” Even so it wasn’t until a few weeks before I turned 41 that I had, as Oprah Winfrey would say, an aha moment and thought that I perhaps had enough material to write my own tale. Because everything I was writing about had happened so recently it was mostly fresh in my head, and in others’, so I was able to check my memory against theirs. However, it was also challenging—time provides perspective, and I had very little of either. It made the revision process a lot more involved than it might otherwise have been had I instead been writing about, say, the year I was 23. That said, part of what I was hoping to do was catch the messiness and intensity of this year, which too much time and perspective likely would have toned down.

This is obviously a memoir, but it struck me that it is (kind of) also a book about public policy. The underlying saving grace of your situation is that you had good, reliable health care and eldercare to fall back on. To what extent were you conscious of wanting to make that contrast between the Canadian health-care system and the American one?

There are a number of things in this memoir that when I wrote it I wondered if readers might find obscure—heath care being one, border patrol stops another—but have since become hot-topic issues. The answer is, while I didn’t set out to make this a commentary on public policy, it’s impossible not to continually note how differently lives are lived when health care is universal. I grew up in Canada and have family and friends there; whether or not you can afford to go to the doctor is not an idea that exists. I now live in the States as a freelancer. Last month my doctor sent me for a breast biopsy and my first question was not “Should I be worried?” (I’m fine), but “How much will my insurance cover?” Americans are so accustomed to thinking like this that even though we know it’s terrible, we still accept it as reality, which is shocking to people who live in countries where health care is not tied to employment. A friend who was transferred here for a year for work while she was pregnant could not understand how women were not rising up in revolt over maternal health-care policies. (This was before 2018.) There’s literally nothing in our lives here that isn’t affected by the lack of universal health care, not one single decision. In the case of my mother, I’m not sure what we would have done. It would have necessitated some unfathomably terrible decisions about care had we been in the States. As difficult as it was to navigate the Canadian system (which is far from perfect), I said a daily prayer of thanks I did not have to question whether we could afford to see her cared for.

This is also a book in which men come and go, but the love for New York City remains constant. Can you describe the moment when you first fell in love with New York? When it broke your heart? When it healed it again? What’s the best place in New York City, in your opinion?

New York has never broken my heart! It definitely exhausts me from time to time, and because I ride my bike everywhere there have certainly been days where I’m convinced it’s out to kill me. But I’ve never actually had a moment where I’ve hated it, felt let down by it, or thought seriously of leaving. (The necessary caveat to that last statement is that I don’t have to consider housing and schooling for children.) I’ve known many people who struggled through their first year here trying to get their sea legs and figure out how it all worked, but for whatever reason, it’s always been a perfect fit for me. I arrived here late on a Friday night in September, took the R train in from Queens the next morning, got off at the Fifth Avenue and 60th Street stop, took one look around, and said, that’s it, I’m home, never leaving. That was more than 20 years ago and has remained true. This comes with its own challenges; a lot of my travels involve me subconsciously asking the question: If I had to leave NYC, could I live here? (To continue the cliché I am inhabiting here, the answer to this question, so far, is yes, Paris.) The best place in New York for me changes with the seasons and with what part of my life I’m struggling with. As I write in the book, I go to Bemelmans on the Upper East Side when I need some old-school New York. I walk the Brooklyn Bridge regularly and have never not been awestruck by it (and never don’t recall we have a woman, Emily Warren Roebling, to thank for its existence). I still shop at Sahadi’s, the Middle Eastern grocer on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. Though truly the thing I love most is a bike ride up Third Avenue in the summer, when the streets are emptier, or through Central Park after midnight in the winter, when the air is sharp and you can sometimes see the stars.

To some extent, this is a book that fits a familiar genre (at least in parts): Girl moves to the big city, finds love (in friendship), finds herself. Do you have favorite books in this genre? Or other heroines that you had in mind as you were writing?

In her terrific book All the Single Ladies, Rebecca Traister talks about how cities have long been a safe harbor for single women. A city provided women with employment, and subsequently some degree of financial independence. It came with a supportive network of other women not available in more rural places, and freedom from family and marriage. I recall at a reading for her book, she noted the city also fills the traditional role of the wife. It’s possible to pay to have someone cook your food and deliver it, clean your apartment; transportation is accessible and comprehensive.

I actually came late to the most famous stories we have about groups of women in the city. I didn’t watch Sex and the City till a year after it ended, by which point I’d already been here for long enough that I could enjoy the truths of the show (and laugh at the excesses) without using it as some sort of guide for how to live. Similarly, I didn’t read The Best of Everything until last year! (Maris Kreizman just wrote a great piece on the influence of this book.) The truth is some of my favorite stories set in New York often have more to do with real estate: Rear Window, Auntie Mame. Or (this is a not a feminist thing to admit!) male protagonists: the Zooey half of Franny and Zooey, and my favorite short story ever, James Baldwin’s Sonny’s Blues. The heroine I thought of most when I was writing this book was Laura Ingalls. Not a New Yorker, but an obsession that rivals the one I have with this city.