The Glorious Performance Art of Grace Jones and Issey Miyake

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Every fanatic of the designer Issey Miyake, who died last week at the age of 84, has an icon who represents for them the work of this awesome genius. Hypebeasts might envision Robin Williams in a purple and blue cargo bomber from Miyake’s Fall 1996 collection as their ultimate grail. Ladies of the canyon may worship Joni Mitchell in her Miyake finery: the singer has admitted to owning “hundreds” of the designer’s pieces. And the general public knows Miyake through his relationship with Steve Jobs, whose plain black turtlenecks, made by the hundreds by Miyake, solidified the Apple co-founder’s public image as a normcore pragmatist who let his design work speak the loudest.

But no Miyake-wearing celebrity comes close to the energy and influence of *Beyoncé voice* Grace Joooones. One of the most significant pop personas over the past five decades, Jones has wielded the spectacular power of the designer’s fantastical innovations to make us stop and look, in turn drawing audiences in with the power of her siren song.

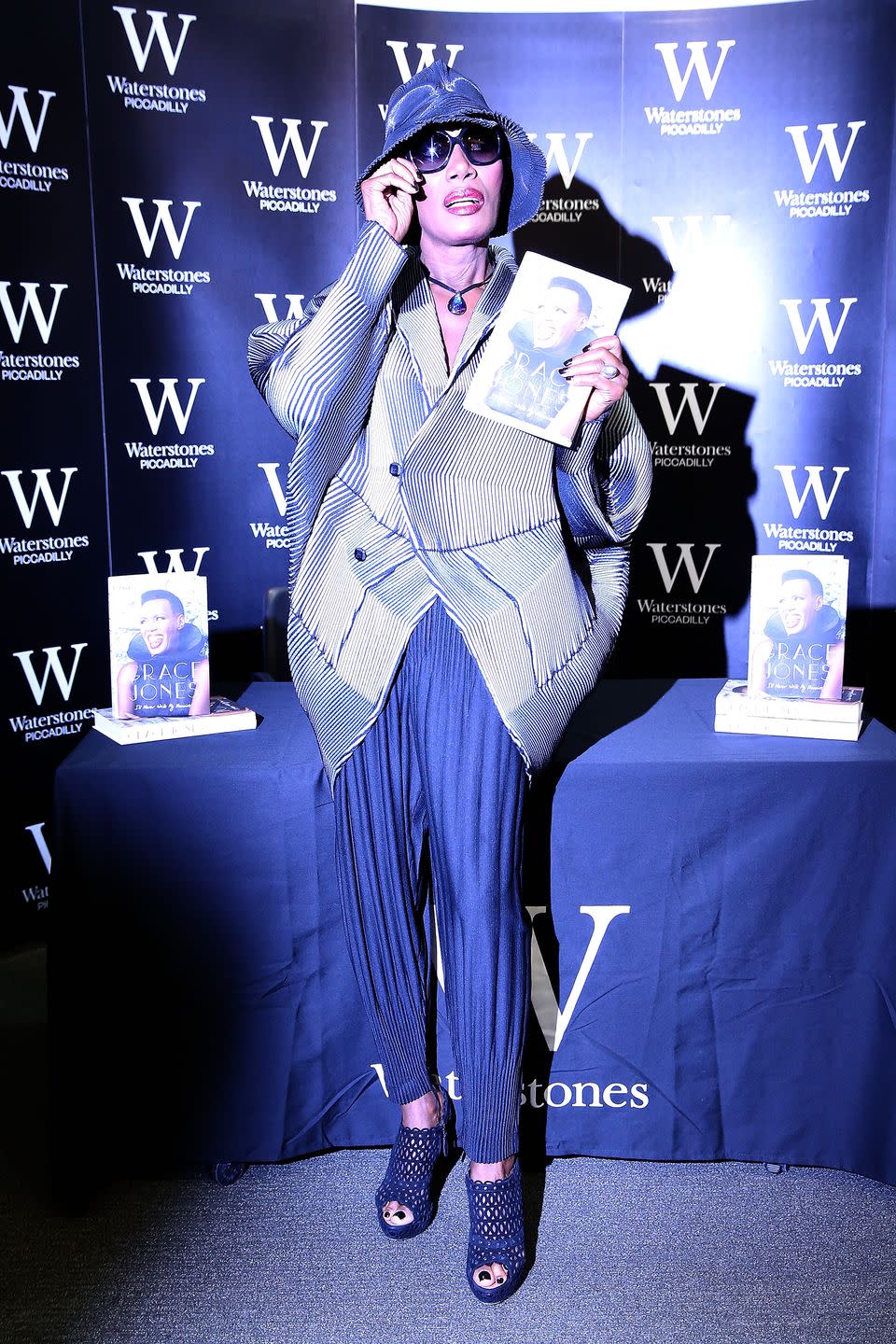

"I wear his clothes every day to this day, and even those pieces I've worn for years still surprise me,” Jones recalled in her 2015 autobiography, I’ll Never Write My Memoirs. (She even posed in his pleated ruff collar for the book’s cover.) “He once said that his clothes are unfinished, and how they get finished is by being worn for years.”

Jones has, indeed, been wearing Miyake’s work for years. Even if you don't realize it, you’ve seen her in his pieces. Still and video evidence of Jones in Miyake’s clothes is the heartbeat that pumps fresh blood into pop culture’s great visual moodboard. In many of the images and moments that have solidified Jones as an icon, she is dressed in Miyake: on the cover of her 1980 album Warm Leatherette—on which a pregnant Jones wears Miyake’s silky, tender but tough bolero—to an iconic 1983 Grammys appearance with Rick James. Of course, she donned Miyake throughout the press tour to promote her memoir.

Jones’s image remained indelible, endlessly remixed by legions of fledgling divas and fashion spreads for nearly 50 years. It also remains singular, and totally individual—in large part, I believe, because Miyake’s clothes helped her carefully craft her image. They helped her give depth to her onstage performances and bolstered her offstage personal style. More than a muse, she is the preeminent practitioner of the core ideals of creation and joy set forth by Miyake. She makes her fantastical image, supported by a foundation of Miyake’s wildest garments, inextricable from the rest of the Grace Jones experience. In doing so, she acts as the pop culture particle accelerator for a creator who believed design comes to life only when it “awakens a sense of beauty, of joy, or of wonder” in the public.

Yet for all the heightened glam of her Kabuki-inflected Miyake looks for stage and screen, Jones knows how to bring his designs down to earth, simply because it’s the core of her wardrobe. For Jones, Miyake’s pleats are what jeans are to the rest of us plebs. She lives and breathes Miyake in amorphous cocoon coats and custom pleated hoods with the casual, quotidian effortlessness of t-shirts and baseball caps. Who else at her level shows up to her own book signing at the Union Square Barnes & Noble and lifts her Miyake top, worn with the nonchalance of a vintage tee, to flash paparazzi on the step and repeat? No one, because no one is at her level. And what an awakening she so expertly inspires.

In a tribute to Miyake posted to her Instagram, model, activist, and Miyake collaborator Bethann Hardison remembers the designer enlisting her to helm casting for “a big show in Japan… that included Grace Jones and other beauties of that time.” This would be a 1976 fashion performance billed as “Issey Miyake and Twelve Black Girls” during which Grace, Bethann, and other models traveled from Tokyo to Osaka to strut for sold-out crowds in Miyake clothing. Recounted in Memoirs, Miyake cast Jones as the leader who would "sing and have multiple roles within what was a fashion show remade as a happening.”

Up until then, Jones was a working model striving to claw her way into life as a theater performer. This event cleared the path to Jones’s future as "not a singer, not a model, not a dancer, not an actress, not a performance artist: all of that together, and therefore something else." It was Miyake’s prescient combination of art, fashion, and celebrity that elevated Jones to the echelon she deserved. Throughout both of their lives, the relationship was symbiotic.

That’s because Jones strikes at the heart of what it means to wear Miyake’s clothing: to be enveloped in its folds it is to be transformed into “something else” beyond the constraints of time, place, or gender. Both designer and performer beckon the public to ceaselessly quest into the depths of modernity, all together made evermore human in our synchronous weaving together of past, present, and future that results in something entirely new and propulsive.

If Miyake’s clothing requires a body to be fully appreciated, Jones is the living embodiment of his principles. As she moves, however slowly, she snatches the rest of us into tomorrow at lightspeed in a spaceship made from gossamer pleated polyester and single threads that can be seamlessly spun into infinitely wearable creations.

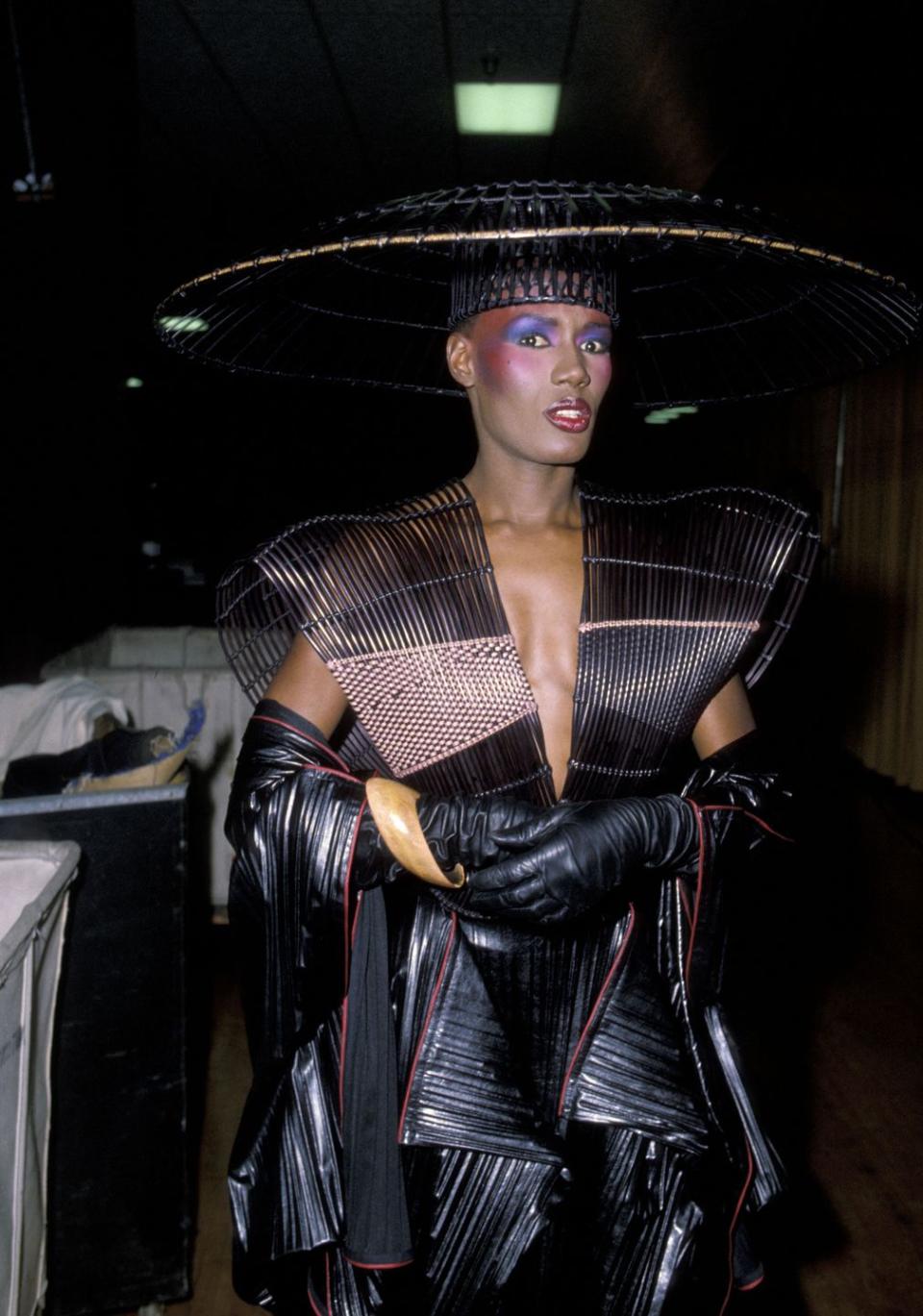

woven rattan vest and synthetic skirt–the same groundbreaking ensemble worn on the February 1982 cover of Artforum, itself a direct challenge to an isolated art world which until then turned up its nose at fashion as unworthy of artistic merit. Only Jones took it up a notch, natch, when she donned the coordinating woven rattan hat not pictured on the cover, repeatedly bumping into Rick James onstage at the Grammys in 1983 and crash landing into living rooms across the world. Through a celebrity moment totally her own, Jones bridged the world of avant-garde fashion and mass culture, solidifying her position as pop nonconformist nonpareil.

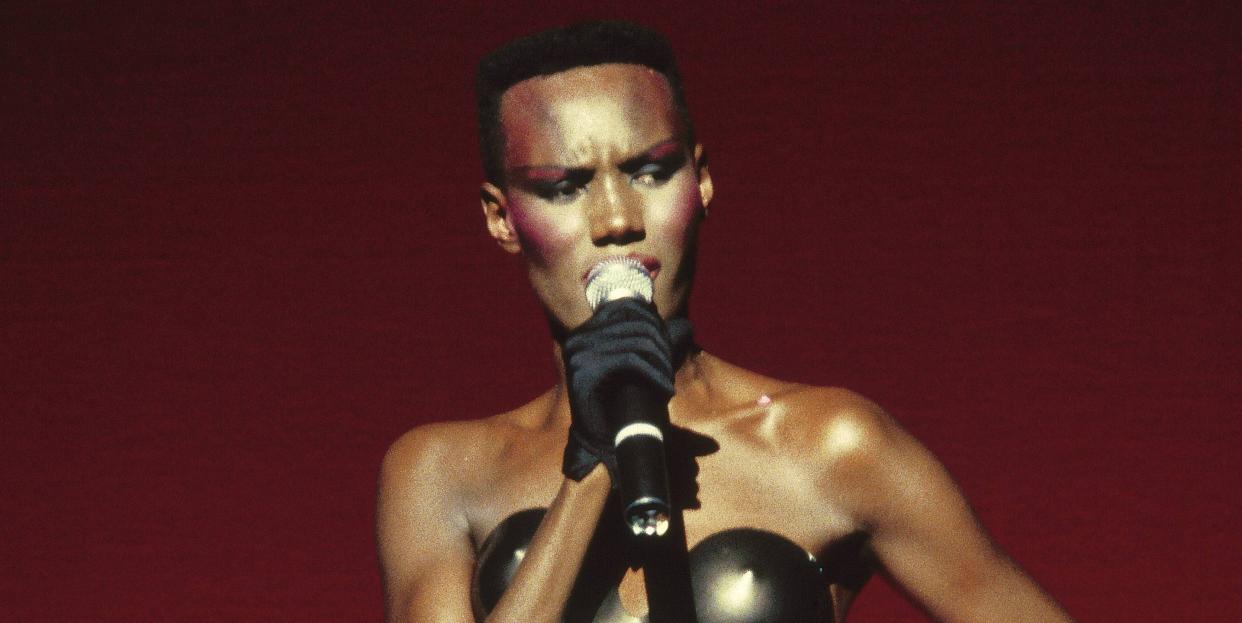

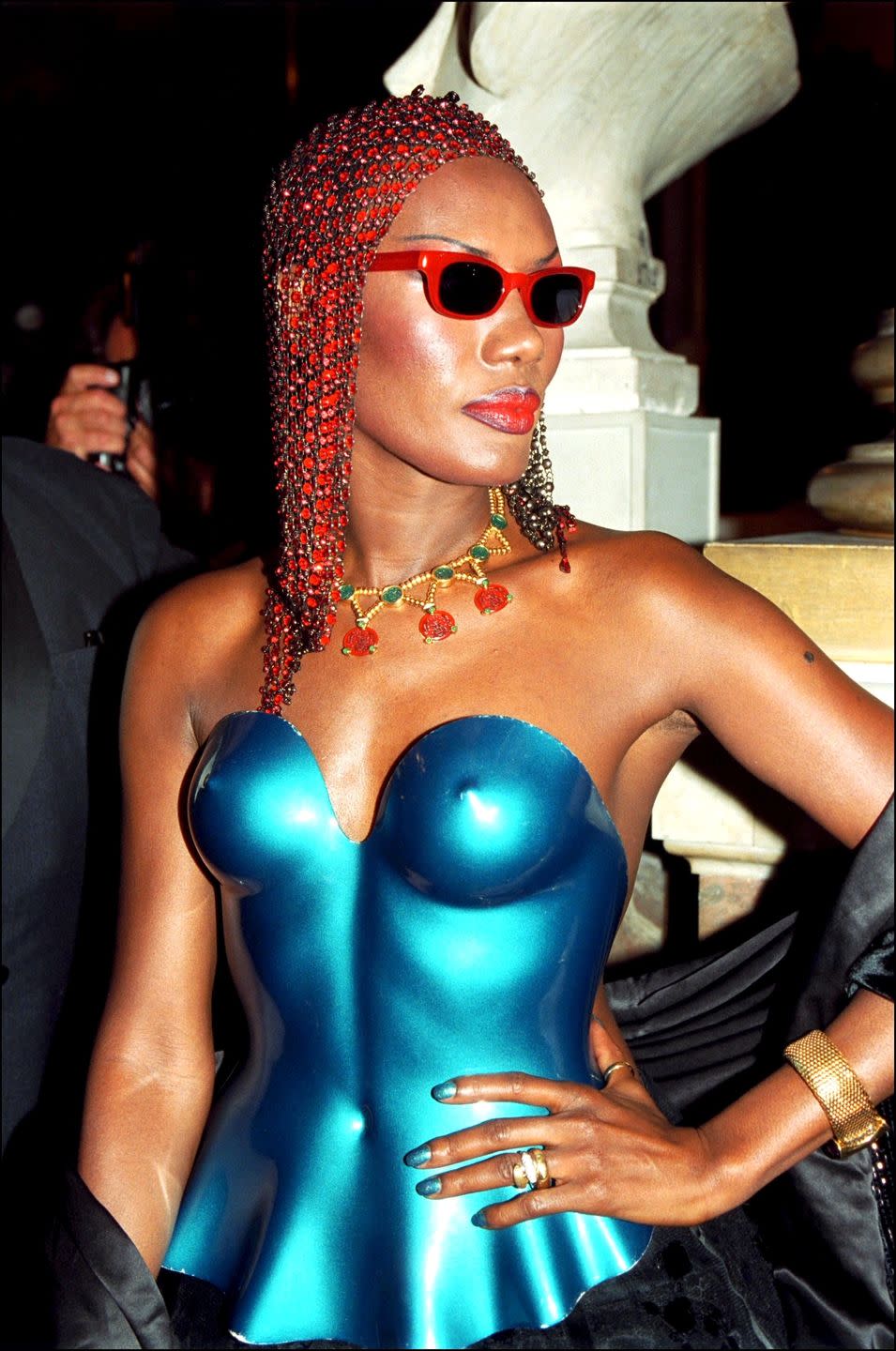

Jones was not only a fan of Miyake’s diaphanous, expandable ensembles—she has repeatedly worn Miyake’s molded breastplates. A nod to Yves Saint Laurent and Claude Lalanne’s 1969 version, Miyake’s both hid the body and exposed it for the world to see (and proved themselves worthy of constant rotation. See, the singular and avant-garde can be sustainable!). With both looks, Jones actively mirrored Miyake’s own expansive push toward the future: if he challenged established western tenets of design and taste, she was radically and declaratively herself, unwilling to conform to the pop music machine’s standards around how a performer, particularly a Black woman, should look and act.

Together they are the anti-gatekeepers of fashion, bringing to life the communal curiosity embedded within the pleats and folds of Miyake’s garments.

Miyake said of his designs, “I get angry if they don’t move.” As a counterpoint, Jones has centered joyous forward momentum as a generative balancing act in lockstep with Miyake, himself a survivor of the destructive force of the Hiroshima bombing.

Jones has continually inspired movement on dancefloors, in manners of dress, and in our understanding of gender. She yanked the experimental into pop culture at large. At the beginning of her career, she credits Miyake with helping her realize that “I was the countdown to an explosion that was always about to happen.”

I hope he got to hear her feature on Beyoncé’s “Move” before he left us.

You Might Also Like