This Glamping Resort Gets Guests Access to Some of the Best Wildlife Experiences in Costa Rica

The rainforests around Arenal Volcano are alive with capuchin monkeys and caimans, tanagers and tree frogs.

Ozzie Hoppe

Sleeping in the treetops at Nayara Tented Camp.If, as it’s often said, we are each the star of our own movie, isn’t the same true for every creature searching for food, a mate, or a home? They’re at the center of their existences, just as we are at ours. There are countless overlapping films, streaming at all times.

Ozzie Hoppe

From left: Arenal Volcano, as seen from Nayara Tented Camp at dusk; nighttime walks at Nayara reveal creatures like the red-eyed tree frog.Costa Rica, which is rightly renowned for its biodiversity, is a good place to watch some of them. The country packs 12 ecosystems and half a million species into its 20,000 square miles. Over half its landmass is forest — a celebrated reversal from the 1990s, when deforestation had eliminated more than three-quarters of the original forest cover. Which makes it the perfect setting to explore the lives of other species, and decenter your own.

Ozzie Hoppe

A howler monkey in the Cañ Negro Wildlife Refuge.When my husband, Alex, and I visited in early June, we got our first taste of this sensation on the nearly three-hour drive north from Juan Santamaría International Airport in San José to our destination, Arenal Volcano National Park. Along the winding route, it was human dominion all the way — city and slum, highways and trucks, fields for crops or livestock — until we hit the rainforest. Walls of green, designed for neither our comfort nor our sustenance, pressed in from both sides. It was as if we had turned the page of a script to find we were extras, not stars.

The park is named for the volcano at its heart, itself a humbling spectacle. Arenal is some 7,000 years old and about 5,300 feet high. Its last major eruption was in 1968; lava flows continued for decades after that. It no longer spews molten rock, but it still vents steam. While Arenal is often obscured by clouds, we got lucky: for five days it was our constant companion.

Ozzie Hoppe

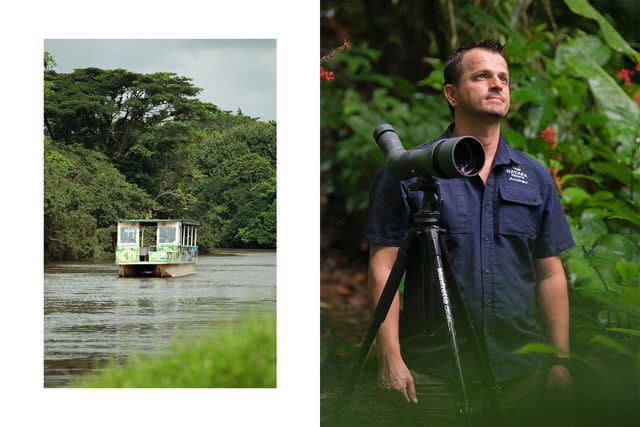

From left: Boating in Caño Negro; Luis Andrey Pacheco Vásquez, a resident naturalist at Nayara.We were staying at Nayara Tented Camp, one of three interconnected resorts just outside the park. While the walls of our tent were indeed canvas, we were hardly roughing it, between our private plunge pool fed by geothermal springs and the remarkably attentive staff, who would zoom up on golf carts to check on our welfare as we walked the property’s curving paths. As a guest there you feel like you are the center of the world. Yet Nayara also provides opportunities for you to embrace your own insignificance, though the staff might not put it in exactly those terms.

Related: Travel + Leisure Readers' 10 Favorite Resorts in Central America 2023

You can do this on the lush grounds of the resort, where over the course of 14 years more than 100,000 trees have been planted, a mini-reforestation of sorts. This makes Nayara a wonderfully verdant environment for its human guests — and a biological corridor for its nonhuman ones, who use it to pass from one rainforest to another. Lounging on our wooden terrace we saw scarlet-rumped tanagers, great kiskadees, the clay-colored thrush, and a toucan flying overhead. Heading to dinner one night, we nearly tripped on a three-foot-long boa constrictor stretched out on the path near our tent. We heard one staffer call them “controllers” because they help keep rodent populations in check. (Sightings on the property are, we were reassured, rare.)

Ozzie Hoppe

Ana Emilia Villalobos, another of Nayara's staff naturalists, spotting wildlife at Mistico Arenal Hanging Bridges Park.On a guided morning nature walk, we saw sloths, strawberry poison-dart frogs, and an abundance of great curassows — essentially tropical wild turkeys. There are similar night walks as well. The resort is a model of happy coexistence: humans being pampered alongside animals living their best lives, the two cohorts occasionally crossing paths.

But to really leave the human world behind, in a setting where humans verge on irrelevancy, requires becoming a different kind of guest. To this end, Nayara offers a range of private tours with naturalists, of which there are 12 on staff.

Ozzie Hoppe

From left: A guest villa at Nayara Springs, one of three Nayara properties in the Arenal region; a great egret at Caño Negro.Our guide for two of our three tours was Luis Andrey Pacheco Vásquez, or Andrey. Early one morning we took a short drive with him to the Mistico Arenal Hanging Bridges Park, clocking the mountain peaks of the continental divide in the distance. The park is a family-owned primary forest through which 16 bridges (the highest is 150 feet above the ground) have been built. We walked for about two miles on a well-maintained path, thankful for the shade and dappled light provided by the dense tree cover. We were thankful, too, that our trip took place outside of peak season, which meant our wait times to cross the swaying, single-file bridges were minimal. (At the busiest times of year, as many as 1,800 people visit a day.)

I have gone on safari in Africa, in search of the Big Five. I was surprised to find what I came to call the Tiny Billion — charismatic microfauna in the wild — to be just as thrilling. But whereas you don’t need much help to spot an elephant, most of what we saw on our Costa Rican expeditions would have eluded my notice without the trained eyes of the naturalists. It felt like being on a treasure hunt with someone who has been studying the clues for years.

Ozzie Hoppe

A colorful lizard at Nayara.The word study is apt, since, in Costa Rica, a full-time, four-year course is required for certification as a naturalist guide. Andrey’s deep knowledge gave us a new appreciation for the intricate intelligence of the natural world. Tree frogs lay their eggs on the underside of leaves over ponds and puddles, for example, so that when they hatch, the tadpoles drop right into the water.

Watching a colorful broad-billed motmot pendulate its double-fan-shaped tail right in front of us, Andrey inferred that it must have a nest nearby. Sure enough, in the dirt bank behind us, he located a small hole and used his flashlight to illuminate a tunnel, perhaps a foot long, at the end of which sat a plump motmot chick. Again and again he showed us what we were missing. A violet-headed hummingbird on a nest. An eye-lash pit viper curled on a leaf. A gorgeous crested owl, its eyes slowly shutting, in a distant tree.

Ozzie Hoppe

A great curassow, one of the many bird species you can see at Nayara Tented Camp.At our feet he pointed out what looked like a mosaic on the move: leaf-cutting ants carrying bits of foliage back to their nests. There they would ferment their collective haul with their own excretions, and later consume the resulting fungus. Each time Andrey saw something he would stop, set up his spotting scope, which zooms in anywhere from 27 to 60 times, and allow us to look. My sense of scale kept shifting, in both time and space: the 700-year-old pilón tree juxtaposed with a blue morpho butterfly that will only live a few months; the nest that is home to as many termites as there are people in the city of San José.

We went on a second expedition with Andrey, driving for about two hours, including 15 minutes on a teeth-chattering road, to a refuge called Caño Negro. We boarded a boat, where breakfast was laid out for us, and Andrey began scanning the trees. Over the journey’s course we saw spider, howler, and capuchin monkeys, some with babies on their backs, snoozing, swinging, and snacking. There was also an astonishing array of birds: anhingas spreading their wide black wings to dry; the purple gallinule; the russet-naped wood rail; the rare jabiru — each more beautiful than the last.

Ozzie Hoppe

From left: Shady pathways wind through the Nayara grounds; each villa at Nayara Springs has its own thermal hot tub.Nature, even in miniature, is full of drama. We watched a caiman (a cousin to the alligator) swim out in pursuit of a young green iguana, which was paddling for its life across the water. It was as adrenaline-inducing as any filmed chase scene, but with higher stakes. (For the iguana, certainly; to be fair, perhaps for the hungry caiman as well.) When the caiman turned back halfway across and the iguana continued on toward safety, we cheered.

To observe the natural world closely, in the company of guides who understand it intimately, is to be reminded that life is precarious for creatures large and small, and all any of us can do is try to better our odds. Andrey pointed out a capuchin monkey descending a branch that leaned over the water. She was going to drink, but instead of putting her face in the water, as we expected, she stuck her tail in, scampered back up the branch, and sucked the water off. Then again: dip, retreat, suck. It seemed an inefficient way to hydrate, but from an evolutionary perspective, Andrey noted, it made perfect sense: put your face in the water and you may lose your head to a caiman. A tail you can live without.

Ozzie Hoppe

A caiman at the Caño Negro Wildlife Refuge.These are the marvelous details of nature, and we gorged on them. My husband, whose usual interests run to history and music, is still talking about why monkeys in the New World have prehensile tails while those in Asia and Africa mostly don’t. (It’s complicated.) And thanks to the trifecta of iPhone, spotting scope, and guides who knew how to pair the two, we came home with ridiculously good photos and videos of even very small or distant creatures. I came to think of the spotting scope as the opposite of the selfie stick: it elevates the hidden experiences of others, rather than your own.

The guides’ knowledge was impressive, and their enthusiasm infectious. On a nighttime nature walk on a former cocoa plantation about a 10-minute drive from Nayara Tented Camp, we spent 90 minutes traversing a half-mile in the dark with a guide named Hanzel Gomez. Let me stipulate that I am not a lover of snakes, of which Costa Rica hosts an unnerving variety. (Comfortingly, it is also one of the world’s leading developers and exporters of antivenom.) But Hanzel’s exuberance at the sight of a rarely seen Costa Rican coral snake was hard to resist. It was truly gorgeous: a moving parade of black, yellow, and red slithering through the roots of a tree. Its glistening skin was a sign of good health, Hanzel said, pleased — and I found myself pleased too.

As we were scrutinizing, through the spotting scope, the amusingly expressive face of the red-eyed tree frog, angry bellows resounded in the distance: howler monkeys, who happen to be some of the loudest mammals on earth. (Given that they weigh about 20 pounds, and first place belongs to whales, which can reach 220 tons, this is impressive.) Most likely a car or truck had roared past, Hanzel said. The monkeys were demarcating their territory with sound. This was their film, not ours.

Doubles at Nayara Tented Camp from $1,200.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.