Giorgio Armani’s Interior Design: What Makes the Cut

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sipping an aperitif at the Bamboo Bar at the Armani Hotel in Milan, those familiar with Giorgio Armani’s meticulous attention to detail know that the positioning of the counter stools has passed the legendary designer’s intense scrutiny. If you find yourself at the Armani Hotel in Dubai, you can rest assured that he has considered the height of the coffee tables in the entry hall and the color of the fabric on the sofas. Checking out the Armani/Fiori at the Emporio Armani megastore below the designer’s Milan hotel, the floral arrangements reflect his admiration for Japan’s aesthetics.

Consistency and cohesion are keywords in Armani’s vocabulary and these apply equally throughout his design world, which extends far beyond the famed fashion collections, and which remain ever so current as he gears up to present the latest Armani/Casa collection during Salone del Mobile.

More from WWD

For the first time, Armani will open to the public the doors of the stately Palazzo Orsini — the company’s historic headquarters — to display the new outdoor range in the garden and his furniture in the beautiful frescoed rooms of the Armani Privé atelier, in a reflection of continuity with the designer’s recognizable style.

Just as he has masterminded the growth and expansion of his fashion empire, which reported sales of more than 2 billion euros in 2021, Armani has built a solid furniture and interior design business. Armani/Casa is present in 29 countries with 40 stores around the world in leading cities from Milan and Paris to New York and Tokyo.

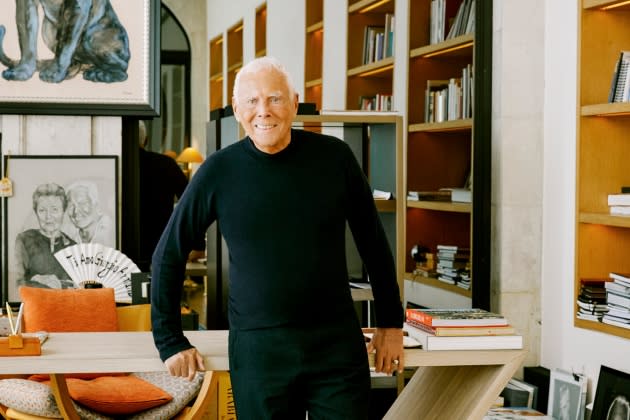

“I try to get by,” he deadpans with a smile, his blue eyes twinkling with humor, during an interview at his apartment in Milan’s Via Borgonuovo, the address of his storied show space near Palazzo Orsini.

While Armani/Casa was formally established in 2000, Armani designed his first piece for the home in 1982, the sharply silhouetted Logo lamp, seven years after founding his fashion brand and ahead of his peers, who have since expanded into the interiors category.

“If you ask me what I think now of all this work, I would say it’s been an immense commitment and continues to be so. However, I do it with pleasure, as there is nothing more beautiful than to see an apartment be born,” he says.

Needless to say, his own apartment is exquisitely — but also surprisingly — furnished. Case in point: a beautifully restored armchair newly upholstered with a leopard print fabric — not exactly a pattern that one immediately associates with Armani.

“It’s a fantastic armchair, revamped but it’s an original from the ‘30s,” he says, noting that he has revisited the model for the Casa collection. “Armchairs are my favorite pieces to design.”

The apartment was originally designed by Peter Marino, but Armani has filled it with memorabilia “of personal, more than material value.” For example, a sweet portrait with his mother takes pride of place, visible from the entrance into the room. Above it is a painting of a black panther.

A striped black and white furry throw is laid on a sage-green sofa, contrasting with colorful pillows with graphic motifs. A sleek light oak desk is flanked by two low bookshelves — “I don’t like high libraries,” Armani points out, although built-in book shelves take up one entire wall.

Two floor-to-ceiling mirrors give further depth to the room, where touches of orange, as in the pillows on the chair behind the desk and on the lampshades with Far Eastern vibes, add warmth to the neutral palette.

Armani has a very clear point of view, but he admits he has fine tuned it over the years, as his first collection was “very severe, squared, angular and sharp.” At the time, he disliked the idea of working with mahogany, wanting to stand out from a crowd of designers who employed that wood, he says.

In time he became more familiar with the interiors category, growing his experience and understanding his own feelings. Those drove him to indulge in his passion for the Far East, Japan and China in particular.

“I did not want to make a collection of pieces that would be coordinated, I wanted to feel from developing one particular theme, but my effort has always been to stay true to certain values,” he says.

These include the bedrock beliefs that “furniture must be comfortable, an armchair welcoming, a sofa suggest rest, a bed should have no edges — because you never know what happens at night,” he says with a small laugh. “Colors must work with one another and in that sense you can recognize my style and aesthetics.”

Art Deco has also been a recurring reference point, which Armani says is connected to his “love for cinema of the ‘30s and ‘40s — and we all know that true cinema was in those years,” he contends.

Asked how he extends this aesthetic to so many different design categories, he shrugs, saying it is “difficult to give a response. It comes from inside, my own taste dominates this choice.”

Armani has formed strong working relationships with some of the most prominent architects and interior designers in the world, from Marino to Doriana and Massimiliano Fuksas, who conceived the designer’s Manhattan and Tokyo boutiques, and Tadao Ando, who created the Armani theater on Via Bergognone in 2001.

At his Silos space in Milan, Armani devoted an exhibition to the Japanese architect’s career during Design Week in 2019. At the time, he praised Ando’s “extraordinary ability to transform ‘heavy’ materials such as metal and concrete into something truly exciting,” emphasizing the architect’s “use of light, a fundamental element that helps shape the character of spaces.”

In 2015, Armani unveiled the Silos site, renovating the 1950 building, originally a granary of the Nestlé company, covering around 48,600 square feet on four levels. The designer himself conceived and oversaw the renovation of the building, which stands on the opposite side of the street from the theater.

The building is modeled after a basilica layout, an open space four floors high with two levels of naves overlooking it on either side. The ceilings are painted black in contrast to the gray cement floors. “I wanted to keep the rough aspect of the Silos as it was,” Armani remarks.

The geometric, regular shapes echo Ando’s own design sobriety. What drives Armani, summed up Ando simply at the opening of the exhibition, is “his desire to do beautiful things.”

Beauty in interior design also depends on the location, as Armani explains that each of his homes has a different atmosphere according to the geography. “I strive to stay true to each location and in connection with the exterior.”

On the island of Pantelleria, he has restored a group of dammusi, the typical local stone homes, into a beautiful summer retreat, “recovering and maintaining the aesthetic of those buildings,” he says.

In Antigua, the style is more American, with white-painted wood and columns, but Armani admits he “took out some of the colonial echoes” to make the house more in sync with his own style.

He speaks fondly of his apartment in Paris’ Boulevard Saint-Germain in an 18th-century building above the Emporio Armani boutique. “The view is beautiful, and the area is always buzzing with people walking around,” he says.

The house in Saint-Tropez reminds Armani of his “first summer trips as a young man” while a restored barn house — Chesa Orso Bianco — in St. Moritz, Switzerland, is a way to enjoy the snow, as the designer points out he chooses his destinations depending on the season and the weather.

It is Villa Rosa in Broni near Pavia, a one-hour drive from Milan, that is the most surprising. It has 26 rooms on land that spans 25 acres, where zebras, llamas, alpacas, deer and parrots roam freely. Its previous owner was Count Franco Cella di Rivara, who invented the Marvis toothpaste brand.

There are few traces of Armani/Casa furniture or contemporary art in the house, as a painting by 17th-century artist Giambattista Tiepolo stands out in a salon and there is a stone lion bought in Paris that dates back to the 18th century. Baroque gold and gilded mirrors reflect fluffy sofas. “I added some very personal elements to the house, it is filled with memories, but I never wanted it to become a museum. It’s a home where I can feel relaxed,” Armani says.

For added atmosphere, he installed five fireplaces in the villa. “I like the scenography at Broni, it reminds me of the palazzo of [1963 Luchino Visconti film] “Il Gattopardo” with Claudia Cardinale, dancing in that wonderful salon,” he muses.

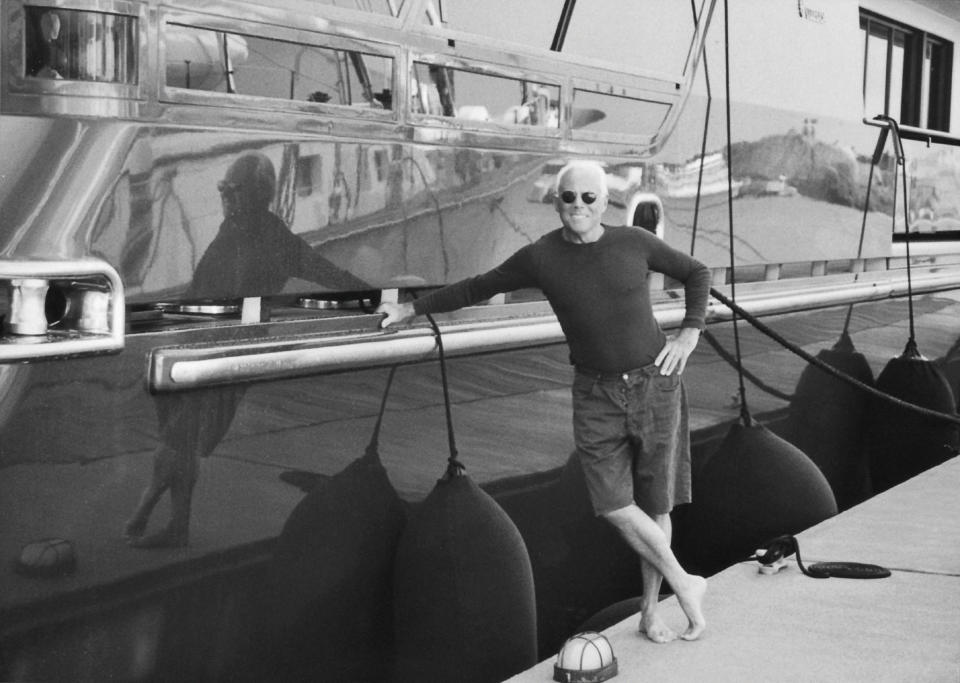

Fireplaces are a must for the designer, who even added one on his personal yacht, Maìn. He oversaw the furnishing and design of the boat as well as the previous one he owned, Mariù.

In his first design project of a commercial boat, last February he presented the 236-foot Admiral motor yacht designed with The Italian Sea Group, which will be delivered in early 2024 — and which already has a buyer. The yacht is the first of two.

“It’s true I love the sea, but I am not a big swimmer, and I take no risks. Also, I see boats for what they are, I don’t want to make them into sailing homes,” he points out.

The designer has also built a solid business with his hotels in Dubai, which bowed in 2010 in the Burj Khalifa, and in Milan a year later, in a venture with Dubai-based developer Emaar Properties PJSC that was established in 2005.

Last year, it was revealed that an Armani Hotel will rise in Diriyah, a 300-year-old site located a 15-minute drive from Riyadh, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which is expected to be completed in 2026. The area is home to the UNESCO world heritage site At-Turaif, recognized as one of the world’s foremost mud-brick cities and the valley and lush palm groves of Wadi Hanifah.

Asked about this new development, Armani says he chose a design that would be connected to the location, but stay away from the risk of becoming “either too ethnic, or too modern, but I still think that a tourist will want to find the atmosphere connected to the place.”

He has not made substantial changes to the existing hotels over the years because he believes returning guests “don’t want to find that everything has changed.” By way of an example, he says, “if you go to La Colombe d’Or hotel and restaurant in Saint- Paul-de-Vence, you don’t want it to be different — there is nothing worse.”

He has not rushed to open a chain of hotels and the final decision on the location is entirely his own. He believes there is no need to stretch this venture. “An English style Armani Hotel in London is pointless, who cares,” he says firmly.

Since 2003, the Armani/Casa Interior Design Studio has provided complete interior design services to private individuals and property developers, including the Maçka Residences in Istanbul and the Century Spire in Manila, among others. Most recently, the 260 Residences by Armani/Casa in Miami, Florida, in a 60-story oceanfront tower designed by architect César Pelli in Sunny Isles have been completed and have sold out.

Armani is also redeveloping his four-level, 16,000-square-foot Madison Avenue store in Manhattan into a 96,000-square-foot building that will house a flagship and 19 luxury Armani/Casa residences, a project to be completed in 2025.

A new restaurant will open in the complex — as food is always a key part of his projects and he was the first to introduce Nobu in Italy in 2002.

Despite his hands-on approach, Armani accepts the idea of clients making the residences their own. “I provide elements to create an atmosphere in a bedroom or a living room, but then I realize these can be tweaked by those living there — as they wish.”

He admits sometimes he disagrees with developers when changes are made for commercial reasons. The projects, he says, “are not about luxury but about atmosphere. There must be cohesion between the furniture’s materials and the floors, they must work with the curtains.”

He concedes he is sometimes “demoralized” by the long lead time necessary to complete interior projects, “given my young age,” he says with a chuckle. “I feel like I should busy myself more with [the interiors and furniture designs] but they take years to see the light.”

And he assesses the competition in the segment. “The offer is huge and I feel comparable with other brands. In fashion — well, that’s different,” he says, his eyes twinkling.

Best of WWD