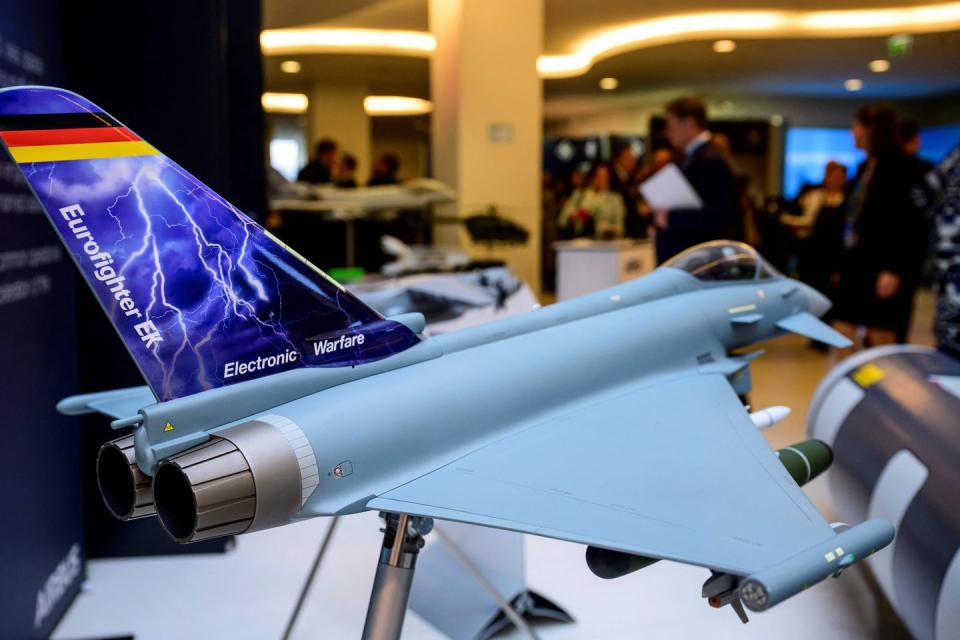

Germany Is Buying the Typhoon-EK Fighter for Electronic Warfare Wizardry

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

On November 29, Germany’s parliament authorized funding for Airbus to convert 15 of their air force’s (the Luftwaffe’s) Eurofighter Typhoon fighters into a micro fleet of specialized Typhoon-EK electronic attack jets. These Elektronischer Kampf (“electronic battle”) jets should, in theory, be capable of locating the position of hostile ground-based radars using electromagnetic sensors—blinding them with powerful jammers and destroying the emitters using home-on-radar missiles.

Electronic attack jets like the U.S. Navy’s two-seat EA-18G Growler have the job of suppressing or misdirecting the enemy’s abilities so that others on the team can safely press the attack.

Since the 1960s, Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) tactics have become vital for warplanes wishing to penetrate enemy air defenses with acceptable odds of survival—especially non-stealth aircraft. And as electronic attack jets remain agile, weapons-capable fighters, they can accompany the planes they’re escorting deeper into hostile airspace and hold their own in a fight.

Currently, the Luftwaffe’s SEAD capability comes from an electronic attack variant of the twin-engine European Panavia Tornado jet. 21 of these Tornado ECR remain in 51st Tactical Air Force Wing. German and Italian Tornado ECRs saw extensive combat use in the 1999 Kosovo war, during which they launched numerous HARM anti-radar missiles (236 and 115, respectively) at Yugoslavian radars. The ECRs also provided electronic escort and reconnaissance during the war in Bosnia in 1995, the operation supporting anti-Qaddafi rebels in Libya in 2011, and the anti-ISIS war in 2015.

But the Tornado, which entered service in 1979, has been phased out of British service and will be retired in the Italian and German air forces between 2025-2030. They will eventually be replaced with more survivable and agile 4.5-generation Typhoons and 5th-generation American F-35A Lightning stealth fighters.

The Typhoon-EK conversion is estimated to cost 384 million euros, or roughly $27 million per plane. It’s unclear which aircraft of the four generations of Typhoons (Tranches 1, 2, 3A, and 4), either in Luftwaffe service or on order, will be converted.

However, the fine print of Airbus’s announcement reveals that the Typhoon-EK has a major shortcoming in its initial configuration: though a press releases claims that its new wingtip jammers will “improve the Eurofighter’s self-protection,” it doesn’t mention any broader jamming capability.

While self-defense jamming is certainly important for an aircraft designed to fight anti-aircraft weapons, it’s not the same as escort jamming able to protect other planes. Indeed, the new Saab jammers appear roughly same as those installed as standard self-defenses on Swedish Gripen-E jets—which are not dedicated electronic attack jets. (The Gripen E also sports a third small emitter on its tail.)

In fact, their installation may come at the expense of existing electronic support countermeasure (ESCM) pods and towed decoy components that are part of Typhoon’s Praetorian DASS self-defense system.

To be fair, Saab’s Arexis system does include larger escort jamming pods that technically can be mounted on Typhoons. But they would be mounted on mid-wing pylons that are usually reserved for carrying extra fuel tanks. For this reason, earlier concept art—suggesting a Typhoon could carry jammers midwing and fuel tanks on the inner wing—isn’t feasible without re-engineering the wing’s interior.

A European alternative to the EA-18G Growler? Airbus proposing Typhoon ECR SEAD variant - with jamming pods and SPEAR EW #avgeek #AirbusTMB pic.twitter.com/486n0mjE0n

— Tim Robinson (@RAeSTimR) November 5, 2019

German defense writer Alex Luck wrote on social media that this configuration “has been a nonstarter for a long time as the inner hardpoints on Eurofighter are not wet [compatible with fuel tanks]. And rewiring them costs so much money it’s not really in the cards.”

This also means that the cancellation of plans to develop a fuselage-hugging conformal fuel tank for Typhoon (one that would free up pylons) further stymies the EK’s jamming options.

Still, the not-yet-funded “Step 2” of Typhoon-EK theoretically envisions procuring escort jamming pods—ones presumably lighter than the current option, and which could fit under Typhoon’s outboard wing pylons. This wouldn’t occur until after 2030, so defense analysts aren’t optimistic that it will come through. Another solution could be developing a single larger jamming pod, which would come at the expense of just one fuel tank on the centerline rack, but still leave room for two inboard fuel tanks.

Luck argues that this is “the best they could whip up short notice without either buying more F-35 or buying Growler. It’s a blatant industrial choice bypassing the needs of the service.” British defense journalist Gabriele Molinelli characterized the Typhoon-EK as “watered down” on social media, due to the failure to find a way to mount larger jamming pods.

Germany previously appeared inclined to procure American Super Hornet and Growler jets instead of developing an electronic attack Typhoon variant. But they then reversed an earlier policy by procuring 35 American F-35 stealth jets to take over conventional and nuclear strike duties from Tornadoes. Though F-35 Block 4s have sensors applicable to SEAD missions and the significant advantage of being stealth aircraft, Germany then decided to fund the development of Typhoon-EK anyway, which is slated for certification by 2030.

The Typhoon-EK is less ambitious than earlier concept art, which depicts a two-seater equipped with three Hensoldt jamming pods and British Spear cruise missiles.

.@AirbusDefence concept images of @eurofighter ECR released at @DefenceIQ International Fighter conference in Berlin. Being proposed in response to German commitment to filling NATO shortfall in A2AD capability by the mid-2020s. pic.twitter.com/dGXsiCNnAl

— Gareth Jennings (@GarethJennings3) November 12, 2019

Besides being in high demand for conventional warfare, electronic attack jets would be important to Germany should they ever attempt to employ the B61 tactical nuclear gravity bombs. These were allocated to the country by the U.S. to be used in event of an apocalyptic nuclear conflict, and must be released very close to their targets.

Arming Typhoon for an electric battlefield

Electronic attack jets typically have two person crews—the pilot focuses on flying and the back-seater concentrates on the intricacies of electronic warfare. The Typhoon-EK’s single-seat configuration might amount to a step back in effectiveness, but Airbus is seemingly counting on a new onboard AI system (by defense startup Helsing) to rapidly analyze radar data mid-mission and suggest appropriate defensive countermeasures to the pilot. That could reduce the burden of simultaneously flying the plane, detecting threats, and employing EW systems and anti-radiation missiles.

The job of actively knocking out hostile radars will fall to American-built AGM-88E Advanced Antiradiation Guided Missiles (AARGM). These weapons home in on the source of radar emissions traveling at nearly three times the speed of sound and stay on target even when the radar is switched off, as operators are likely to do when they see missiles racing towards them.

Germany originally procured roughly 1,000 older AGM-88B Block IIIB missiles for its Tornado ECRs. Finally, in 2019, the country’s defense budget committee approved the purchase of 178 AGM-88Es (plus eight training missiles and other ground-based systems) from the U.S. for 105 million euros, with production mostly undertaken in Germany by Diehl Defense. The AARGM has a range of up to 92 miles when launched from high altitude (or 15 miles when released by a low-flying aircraft) and is designed to shred radar antennas with its proximity-fused, 145-pound fragmentation warhead.

This AGM-88E retains prior models’ new GPS navigation and home-on-jammer capability, while adding a millimeter-wave radar seeker enabling detection and tracking of moving targets. It also features a terrain image-mapping reference library and inertial navigation systems to improve accuracy in the cruise phase, and a satellite datalink to transmit photos of the target just prior to missile impact.

A larger-diameter extended-range (max 186 miles) variant—the AGM-88G AARGM-ER—is also available, but Germany has yet to procure it.

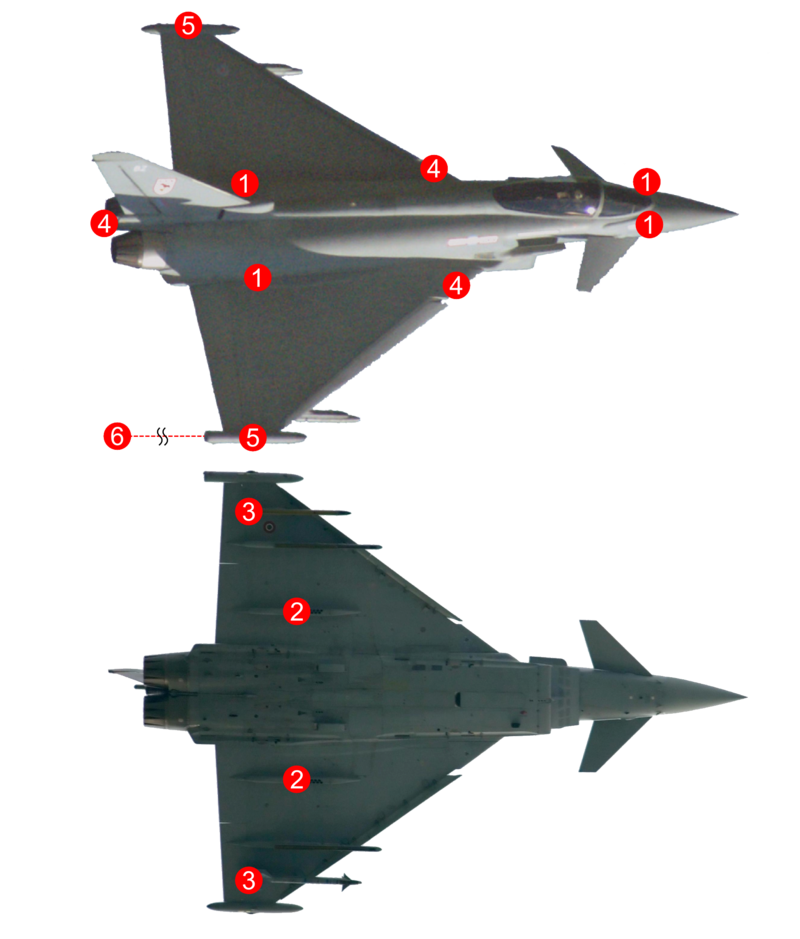

The Typhoon-EK’s electronic wizardry will primarily come courtesy of Swedish company Saab, and its Arexis family of modular electronic warfare systems. This includes a digital radar-warning receiver (RWR) and electrooptical Missile Approaching Warning System (MAWS), providing all-aspect coverage for self-defense against both radar- and infrared-guided missiles. Wingtip pods will also house an interferometric Emitter Location System to find the precise location of hostile radars and retain that information, even if the radars are turned off.

But Arexis’s key items are two kinds of jammers: small self-defense jammers on the wing-tip, as well as two larger EAJP pods (weighing 770-pounds) optionally carried underwing—the latter of which apparently won’t initially be featured on Typhoon-EK.

Arexis incorporates both internal L-Band and S-Band solid-state Gallium-Nitride AESA antennas, as well as external VHF and UHF antennas. They work in tandem with passive ultrawide-band digital receivers that feature Digital Radio Frequency Memory (DRFM) tech, which allows the system to detect and memorize the frequency and bandwidth of hostile emitters. That not only generates valuable intel, but enables the jammer to rapidly mimic those signals for deception purposes—blaring out misleading velocity and vector returns, or even creating false ‘ghost’ targets indistinguishable from real ones to hostile receivers.

Saab’s promotional materials claim that Arexis can be directed to suppress multiple targeted radars simultaneously, and that it is effective against large, low-band radars (with some potential to detect stealth aircraft), the X-Band radars on fighter and anti-air missiles, and the big radars on early-warning planes like Russia’s A-50 Mainstay.

But it is unclear exactly which capabilities don’t overlap between the wingtip pods and the more powerful EAJP pods. As EAJPs are offered to supplement the Gripen-E’s wingtip pods, it is clear that the latter are insufficient in and of themselves for electronic escort missions.

Germany’s need for SEAD

The constrained impact of Russia’s manned airpower on the war in Ukraine has highlighted that even Ukraine’s old (but admittedly numerous) Soviet air defenses could prevent Russia’s non-stealth warplanes from venturing deep into Ukrainian airspace. And those deeper targets—like supply and reinforcement convoys, trains, or command centers and depots—are arguably the ones against which air power is most effective.

Though Russia doesn’t have dedicated electronic attack planes, it does dispose of many electronic warfare pods and radar-homing missiles—ones that its Su-35S fighters and Su-34 fighter-bombers could employ in the SEAD mission. And Russia did try to knock out Ukraine’s air defenses early in the war, particularly destroying many large, immobile radars. But Russia’s effort failed, largely due to Ukraine successfully moving most of its mobile systems at the onset to dodge the initial strike

Russia’s experience highlights that a substantial and sustained SEAD effort is needed to enable non-stealth fighters to penetrate hostile airspace with dense air defenses. Even stealth fighters benefit from SEAD support, as their stealth isn’t strictly impervious.

In principle, the Typhoon-EK could attract interest from other operators of Typhoon jets—most notably Italy (which will retire its Tornado ECRs by 2025), Spain, the UK, and/or Saudi Arabia (though, for now Germany, is unwilling to authorize sales to Saudi Arabia due to human rights concerns.) If so, such customers may insist on installing different systems than the ones Germany settled on for the Typhoon-EK.

Germany itself might consider converting additional Typhoon-EKs if the first order proves satisfactory. After all, in the event of a major conflict with Russia and its deep arsenal of surface-to-air missile systems, demand for electronic attack support would greatly exceed what 15 jets can provide. The many non-stealth Typhoon jets planned to serve beyond the 2060s would require support to conduct penetrating strikes or offensive counter-air missions in a major conflict.

Nice screengrab of the #A400M in the #luWES standoff jammer configuration, via @rich_scott2. Worth noting this is a concept, and the Luftwaffe have not yet made a decision on which airframe will host the capability. pic.twitter.com/JTmqrOIV2k

— Gareth Jennings (@GarethJennings3) May 17, 2023

Germany is also pursuing a wider-reaching electronic warfare program called IuWES, which includes proposals for converting ten Airbus cargo A400M cargo planes to carry powerful stand-off jammers to be used for disabling low-band early warning radars and communications. Unlike electronic attack jets, these larger, slower aircraft would perform their mission at standoff distance—ideally beyond the effective reach of long-range anti-aircraft missiles. This operating concept is becoming riskier, as Russia has increasingly begun to make use of R-37M air-to-air missiles in combat over Ukraine, which have a theoretical max range exceeding 200 miles.

Ensuring that Step 2 is funded, in order to obtain a viable escort jamming pod, is also vital for the Typhoon-EK to replicate the capabilities of the due-for-retirement Tornado-ECRs. Without that, the modified Eurofighters will lack a key arrow in their quiver that the Tornado ECRs they’re replacing already had.

You Might Also Like