George Floyd's killing turned them into activists. What are they doing now?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

On the night of July 25, Alexander “Bear” Matthews sat hunched over in a jail cell in Douglas County, Nebraska. He was fuming.

Just a few months before, Matthews, 24, was embarking on a career in videography after serving a year in prison for selling THC oil to friends at the University of Nebraska Omaha.

But the killing of George Floyd on May 25 had pushed him into the streets, and that activism had landed him in another cell, this time on two misdemeanor charges — resisting arrest and obstructing a highway.

Matthews was seething because the mass arrest that included him and many other protesters that night seemed like “an act of war,” he said. “They were trying to infringe on our First Amendment rights.”

“It made me want to come back harder,” he added.

Now, six months after a cellphone video showed then-Minneapolis police Officer Derek Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck for approximately eight minutes, Matthews’ life remains transformed — and the feeling he had in the cell that night is as potent as ever.

In small towns and cities with little, if any, recent racial justice activism, newly mobilized protesters like Matthews helped create what Douglas McAdam, a sociologist at Stanford University, called one of the most expansive and diverse protest movements in American history. It's prompted substantive changes as well as symbolic gestures, he said, and unlike earlier movements, its reach has been vast.

“We saw the protests spreading to overwhelmingly white, suburban and rural areas,” said McAdam, an expert on social movements. “There’s no precedent for that.”

It isn’t clear how many of those new activists have remained mobilized — or where the movement they helped kick off is headed, McAdam said. But from California’s Central Valley to Omaha, from suburban north Florida to the little town of Bethel, Ohio, four of these activists have remained committed to the fight for racial justice.

These are their stories.

Alexander "Bear" Matthews

Matthews always thought he’d be a teacher. Before going to prison, he was studying secondary education and social sciences at the University of Nebraska Omaha. But his felony record scrapped those plans, and after his release in October 2018, he started making videos for local musicians and businesses.

In prison, he’d read books by radical Black thinkers and activists like Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver and Frantz Fanon, and they’d shaped his thinking about oppression and liberation. But Matthews had never acted on that knowledge. After Floyd’s killing, they were top of mind as he watched — from the comfort of a computer screen — a livestream showing protesters getting tear-gassed by police. So he took to Facebook and wrote a post about it — a move he regretted almost immediately.

“I’ve never experienced such shame and guilt and disgust in myself,” he said. “I was succumbing, like all of those people who have so much to say but aren’t doing anything about it.”

The next day, he went to a protest in downtown Omaha, and within weeks he’d fallen in with a newly formed group called ProBlac that’s focused, in part, on advocating for racial justice. He attended a sit-in at the mayor’s office. He protested a budget hearing at City Hall. And on July 25, Matthews led dozens of people calling for justice in the May 30 killing of James Scurlock, a 22-year-old Black man gunned down by a white bar owner in Omaha.

Matthews led the group across the city’s Farnam Street bridge and into a blockade of police officers telling them to immediately disperse. When they didn’t — with Matthews repeatedly announcing that they were protesting peacefully — officers tackled and arrested him, then placed him in solitary confinement for nearly 24 hours, according to a lawsuit that ProBlac and the American Civil Liberties Union-Nebraska filed last month.

The suit, which names the city of Omaha and its police department as defendants, claims that the officers used excessive force when they “indiscriminately” — and in some cases from point-blank range — fired pepper balls, a chemical agent, at protesters. The suit says 125 people were arrested that night, including dozens who were packed into a single jail cell.

ProBlac and the ACLU-Nebraska are demanding that police halt practices that they say restrict free speech and make it too easy for officers to use chemical agents on nonviolent protesters.

Neither the department nor the lawyers defending the city responded to requests for comment, but in a statement posted a few days after the protest, police said that Matthews hadn’t obtained a parade permit for the event and that he and others were breaking the law when they walked in the street. Police only fired the pepper balls after a noncompliant protester rode his bike toward them, the statement adds.

“Public streets are not forums for protesting,” the statement says. “Extreme danger exists by entering an active roadway, without prior authorization and planning with local authorities.”

The police response that night was partly responsible for tempering what Matthews described as the kind of burgeoning racial justice movement that he’d never seen before in Omaha.

Still, that movement has continued to grow, he said. ProBlac now has 75 members who — while it was still warm outside — attended weekly protests in a section of downtown Omaha they’ve dubbed “Liberation Square.” Members have helped organize and promote events calling for justice in the killing of Zachary Bearheels, a 29-year-old Native American man who died after police officers shocked him a dozen times in 2017, and they've launched a “copwatching” effort to document potential police misconduct. An education program will aim to offer insights on subjects like “intersectional feminism,” while a canvassing effort will try to better understand the needs of Omaha’s Black and Latino communities.

“This is our civil rights movement,” Matthews said. “This is the start of a long, long fight.”

Alicia Gee

Alicia Gee knew she was a long shot. The 36-year-old teacher was running for state representative as a Democrat in the ruby-red slice of southwestern Ohio where she lives. She was a write-in to boot, one who filed her paperwork on the last day possible — Aug. 24 — to challenge a previously unopposed Republican.

Earlier that day, an official from the Clermont County Democratic Party had reached out and asked if she’d run. Another possible candidate had died, and the official, Patricia Lawrence, had thought of Gee after learning of a demonstration she’d organized a couple of months before in the village of Bethel, population roughly 2,800.

The event drew nationwide attention, and before it was over, village officials had declared an emergency and imposed a curfew. Law enforcement officers from across the county were dispatched to assist the village’s six-officer department.

But that wasn’t what Lawrence was focused on.

“To have that protest in Bethel, I thought it took so much courage,” Lawrence said.

Gee, who grew up there, had been to protests before, but never in her hometown and never in support of racial justice. But after the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, she wrote in a Facebook post, it was time “to show my very monochromatic town that Black Lives Matter.”

She aimed to bring out fewer than 100 people for an hour or so on a Sunday afternoon in June. But things didn’t go as planned.

Before the event, a local drag racer had warned via Facebook Live that Black Lives Matter was coming “to bring hate to our town,” according to BuzzFeed. “I hope we outnumber those people a thousand to one, and not let that s--- happen here in our little town of Bethel.” (The drag racer, Lonnie Meade, did not respond to an interview request.)

Hundreds of counterprotesters from three motorcycle gangs, a Second Amendment rights club and a pro-police group flocked to Bethel that Sunday and overwhelmed the space that Gee had secured through the police department, village officials later said.

A series of sometimes violent and ugly confrontations followed, including one shared by Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, depicting a man punching a protester in the back of the head while a police officer stood a few feet away.

Brown called the encounter “shameful.” The village’s mayor, Jay Noble, called the “law-breaking behavior” “appalling and disgusting.” Bethel Police Chief Steve Teague said he had so few officers to monitor the event that “preservation of life” took priority over minor assaults. He added that the officer in the tweet hadn’t seen the punch get thrown.

Five months later, Gee’s view of what happened that day veered between optimism and anxiety. She was proud of the love and support that she and her fellow protesters showed for Black lives, she said, but for months, her stress levels would spike every time she heard a motorcycle rumble by on the rural road in front of her home.

Still, Gee tried to advance what she started. A couple of weeks after the demonstration, she and other locals co-founded Bethel’s Antiracist Movement, a community group trying to resurrect the traditions of the town’s abolitionist founders. And after Lawrence reached out to her, she agreed to run for the state Legislature.

Gee didn’t know when her district had last been represented by a Democrat, and she had so little money her yard signs were recycled from a judge who’d run in a previous election. Gee just flipped them around and added her name.

But the issues she cared most about — workers’ rights, universal health care, access to free education — were an extension of her push for racial justice, she said, a way to “break down the institutions” that perpetuate racism.

“If I can work within the system and build it back up into something equitable and just, there I am doing that,” she said.

Gee didn’t expect to win. The important thing, she said, was to let voters know there was an alternative, and to let her competitor know he wouldn’t get 100 percent of the vote.

Gee netted just under 2,100 votes, or roughly 4 percent, a tally that turned out to be one of the more impressive among statehouse write-in campaigns, according to unofficial results. She isn’t sure if she’ll run again, but she’s tempted.

“In my normal life, I try everything twice,” she said.

Jaspreet Kaur

A few days after George Floyd’s killing, Jaspreet Kaur was in the living room of her family’s home in Ceres, a city of roughly 45,000 in California’s agricultural heartland, the Central Valley.

Kaur, 27, pulled up a letter on her laptop and asked her father — an ice cream distributor who migrated from Punjab, India, in 1986 — to read it out loud. The document was written in his native language, Punjabi, and it connected anti-Sikh discrimination with the long history of institutionalized violence against Black Americans.

“Some of us are told we’re terrorists,” the letter read. “But for the most part, it has not been the case that the police gun us down for simply existing.”

Kaur’s father, Maghar Basra, 64, and mother, Kamaljeet Basra, 56, were moved by the document. The actions of the Minneapolis police reminded them of the corrupt, brutal authorities back in India, Kaur recalled. It also underscored something that many among the Central Valley’s vast population of older Punjabi transplants hadn’t fully grasped.

“This has been happening for so long,” she recalled her parents saying. “Why are they still being murdered in the streets?”

To Kaur, the letter had been a necessary introduction — not just for her own family, but for all the young people of Punjabi descent who cared about how police violence affects Black Americans but didn’t know how to talk to their parents about it. This was especially true for someone like her father, who came from a poor family and had spent years with his head down, working hard, with a simple mantra in mind, Kaur said: “We don’t want any trouble.”

The letter was drafted a few years ago by the community group that Kaur works for as an organizer, the Jakara Movement. But after May 25 it gained new urgency. Even though Kaur’s job is to get all those young people civically engaged — and even though she speaks Punjabi fluently — she found herself stumped, unable to call up the right words to talk with her parents about the issues raised by Floyd’s killing.

And she wasn’t the only one.

“Kids were calling us and asking about it and we’re telling them, ‘Have these conversations at home,’” she recalled. “They’re like, ‘We don’t know how.’ And I was like, ‘I don’t even know how.’”

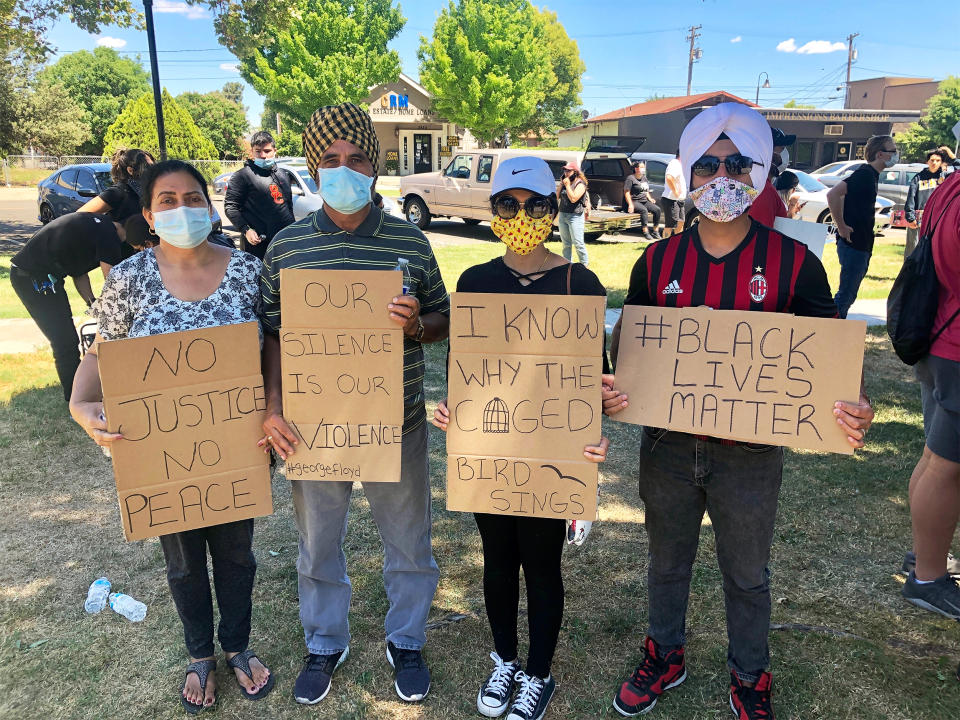

A few days after Maghar Basra read the letter, some high school students in Ceres organized a protest. Basra told his family they should go. So Kaur grabbed a Sharpie, scribbled on some signs, and she, her husband and her parents marched through downtown Ceres with a few hundred other people on a Sunday morning.

It was a first for their family — and for Kaur’s hometown, where she’d never before seen a protest.

The letter that energized the Basras was circulated widely — among Sikh truck drivers and religious organizations, on Whatsapp groups and Radio Punjabi USA. Kaur heard from students and colleagues that it seemed to be reaching other parents, too.

But the letter is just one part of a broader approach that Kaur — and the Jakara Movement — are taking: the group developed a series of short videos that are recorded in Punjabi and grapple with issues like the school-to-prison pipeline and how Sikhs have benefitted from the Black American struggle.

The group’s youth summer program, which usually visits Pismo Beach for a week, instead held discussions via Zoom on Black Lives Matter. A leadership retreat for high school and college students in August saw panel discussions on the same subject.

As for how Floyd’s killing and its aftermath had transformed her parents’ thinking, Kaur remembered a phone call from over the summer that she overheard between her father and a friend. The friend was pushing back against the protests, saying, among other things, that “all lives matter.”

Basra pointed out that if someone in the Sikh community had been targeted, it would make little sense to “bring up random other people,” Kaur recalled, paraphrasing her father. “You need to focus on the situation for what it is.”

Afterward, she offered her father some close-to-her-heart praise: “I was like, ‘Dad, you’re a community organizer now.'”

Kevin Conner

Most mornings, after Kevin Conner drops his son off at middle school in suburban north Florida, he drives home and swaps his sleek Tesla sedan for a hulking Ford F-250.

This switch, Conner said, is a rule: Unlike him, his son is the low-profile type.

On any given day, the doors of Conner’s pickup might be scrawled with various messages — “jail killer cops,” “Black Lives Matter” or, more recently, the number of people killed by coronavirus in the United States followed by the phrase, “Trump Death Clock.” Attached to the bed of the pickup, he might have a giant Black Lives Matter flag. Or one that says, “I can’t breathe.”

Then, Conner, 43, will head out. Sometimes he’ll drive to a nearby county, or to the other side of Jacksonville — anywhere in this mostly conservative region that hasn’t already been “saturated” by his one-man protest, he said.

“It’s mass media to me,” he said. “They’ve been exposed to it. They know Black Lives Matter doesn’t mean your town is going to be burned down.”

Conner isn’t the most obvious choice for a messenger: Two decades ago, he was a young Republican in his 20s protesting the Florida recount during the presidential contest between George W. Bush and Al Gore. Back then, recalled longtime friend Chris Haney, Conner was a church-going financial adviser who wanted to have a family and do missionary work in China. “He was very different when we met,” Haney said.

When Floyd was killed, Conner wasn’t oblivious to the disproportionate violence that Black Americans face. He’d been moved by the 2012 killing of Jordan Davis, a Black teenager gunned down at a Jacksonville gas station by a white man furious about Davis’ loud hip-hop.

But after May 25, two things happened: A CNN crew covering the aftermath of Floyd’s killing was arrested on live television, and the then-sheriff of Clay County, where Conner lives, promised to enlist local gun owners to help crack down on “lawless” protesters.

Conner was appalled by what he saw as a threat to free speech. With ample newfound free time — he’d recently sold the marketing firm he founded a decade before, effectively allowing him to retire — he got some flags, wrote on his truck and started cruising around Clay County.

Occasionally, he’d post encounters with drivers enraged by his message. Sometimes, he’d stand at an intersection by himself, gripping a flag. Haney said he started getting notes from friends who’d spot Conner on the street. “I see Kevin on the side of the road — what’s he doing?” he recalled one of them saying. “I’m like, well, he believes this is wrong.”

Conner also started organizing protests around the region, including a small one in nearby Baker County, where a courthouse mural features three hooded Ku Klux Klan members on horseback. The event featured a prop plane that Conner hired to fly over with a banner that read, “TAKE IT DOWN BAKKKER COUNTY,” as well as a jarring encounter between a young Black woman and an older white woman in a crowd of counterprotesters.

“Why don’t y’all care about us?” the young protester tearfully shouts. The older woman appears to brush her off before calling the protesters “freaks.”

Before the election, Conner had begun focusing on politics, adding a “Biden 2020” flag to the bed of his truck and trolling Trump events. He joined a caravan of pickups, swapping his BLM flags for the Soviet Union hammer and sickle and a Gadsden "Don't Tread on Me" flag. And he and several others attended — then disrupted — a Trump rally in Jacksonville before being escorted out.

Conner isn’t sure where the movement is going, but he has no plans to move on, especially now, after having experienced just a sliver of the “ugliness” that Black people have endured for generations.

“Some people can let that go,” he said. “I can’t.”