Generation XX: How Kaws Short-Circuited the Art World

I'm slaloming a mess of titans. To be more precise, I'm standing inside the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit in the final moments before Alone Again, a new exhibition by the artist KAWS, opens for a crowd of VIPs.

Every which way I turn, I find myself unwittingly confronted by a tweaked-out member of KAWS's odd mob of massive carved wooden sculptures. The most common presence is the artist's iconic character Companion. (Imagine a Mickey Mouse-adjacent creature with a skull-like face, cauliflower-esque four-chambered ears, and KAWS's signature “XX” eyes.) And yet, despite their alien nature, the sculptures each exude familiar emotions.

Take SMALL LIE, for example: The eight-foot figure stands slump-shouldered, knees knocked, eyes glued to the ground. There's incredible pathos. Or AT THIS TIME, wherein Companion stands almost nine feet tall, back arched with hands cupped over eyes, conveying a kind of muted shock and disbelief. Not far away is FINAL DAYS, in which Companion is on the move, stepping one foot in front of the other, arms outstretched, doing a low-key Frankenstein strut. Given the fact that all the pieces are taller than me, the overall effect of standing amid the bizarre cluster is that of being fully submerged within a twisted Venn diagram of awkward human feelings.

Running along the back of the room is a 62-foot-long, 12-foot-high site-specific wall painting that fills the cavernous space with brightly vibrating energy. It is adorned with a trio of 6-foot-high-by-10-foot-long canvases. Each one is a teeming tangle of abstracted tentacle-like shapes over a background more reminiscent of the artist's earlier cartoon-inspired geometric planes. The synergy of all three elements comes together to elicit a sensation of being both transported and slightly held against my will in a kind of psychedelic Land of the Lost.

“Clearly there are elements of color field. There's amazing line work. And, of course, abstraction,” says MOCAD executive director and chief curator Elysia Borowy-Reeder, walking alongside me. “These paintings are really monumental.”

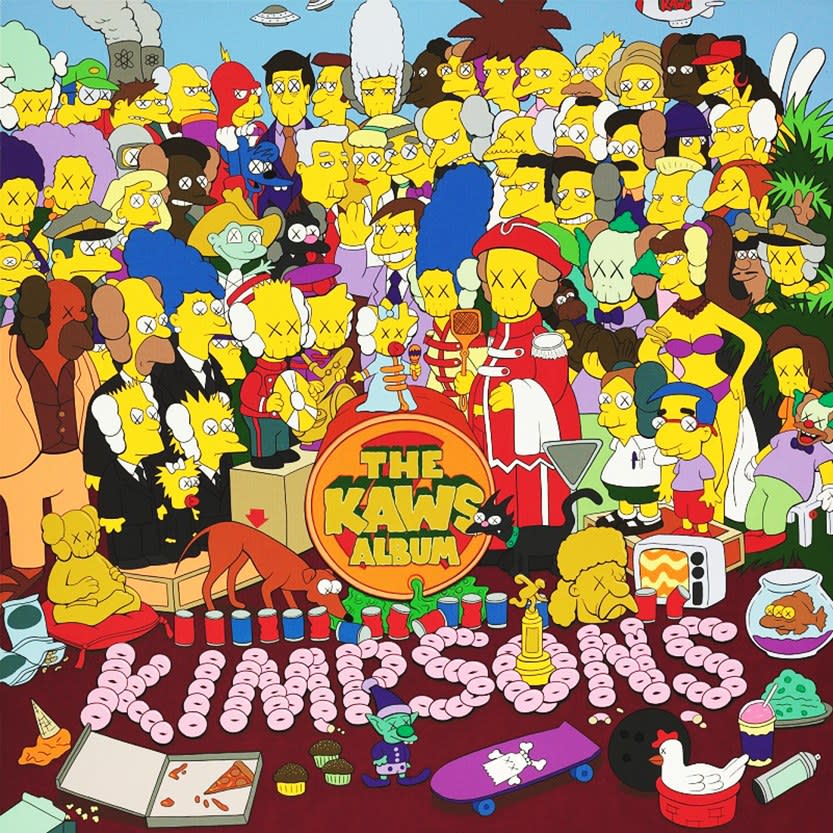

And this is a monumental show for MOCAD as well, at a moment when the appetite for KAWS worldwide is nothing short of rabid. To list just a few notable recent KAWS headlines: There was his 121-foot-long inflatable sculpture that floated in Victoria Harbour during Art Basel Hong Kong in March; a 33-foot-tall version of his newest character, BFF, made out of pink flowers, as the centerpiece of Dior's show at Paris Fashion Week; a line of clothing for Uniqlo that sparked Black Friday-style chaos and actual violence; and a record-setting $14.7 million auction of THE KAWS ALBUM—a 40-inch-by-40-inch painting, and homage within an homage, that uses the artist's “Kimpsons” motif to reimagine a Simpsons version of the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover. Any of these might have been a crowning achievement to an artist's career. For KAWS, it just amounts to what he did this past year.

And yet, sitting with KAWS—a.k.a. Brian Donnelly—the next day in Detroit, I was hard-pressed to glean, based on his understated demeanor, the staggering amounts of high-profile work he is producing and the roster of side projects he is currently involved in. This commitment to spreading oneself around is a sea change in the contemporary-art world. Projects of the sort KAWS takes on—a line of clothing, a product redesign—that were once considered taboo, or even career killers, for an artist on the hunt for a serious career are now understood to be part of the contemporary artist's purview. They are not just “acceptable” side hustles, but downright sexy additions to the portfolio. To someone like Borowy-Reeder, whose extensive and varied museum career threading through Raleigh, Chicago, Milwaukee, Los Angeles, and now Detroit has afforded her the POV of a kind of enriched outsider, the prospects of what a KAWS brings to the landscape of contemporary art is a welcome sign of the changing times. “The palace gates might still be somewhat closed—and there's a moat,” she says. “But I think it was Virgil Abloh who said, ‘How many collaborations is too many?’ He's mixing street and ready-to-wear fashion and killing it. And I hope more people get inspired by that model or lens of freedom, working on the outside, pushing in. With people like KAWS and Abloh, things could get really exciting.”

When KAWS was coming up in the late '90s, he was met with resistance by galleries and managed to book scant few shows. Despite the demonstrated success of “street artist” forebears like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, KAWS—who'd made a name for himself initially with graffiti-style tags and urban installations—struggled to get past labels like “too street” or “too illustrative” or “too commercial.” He was, for better or worse, relegated to success outside the gallery. But in the past decade, as the line between high and low in art has blended considerably and the sorts of side endeavors that KAWS has readily embraced since jump have become par for the course, KAWS's approach to being a contemporary artist has dovetailed seamlessly with what the moment craves most.

In Detroit, I ask KAWS if he approaches any of his paintings, installations, or collaborations differently, if maybe there is an inherent hierarchy based upon scale or degree of cultural significance.

“For me,” he says, looking at me like I'm speaking Sanskrit, “it's all the same thing—there's no difference between any of the projects I do.”

And that right there is probably what has made him, gradually and then suddenly, one of the best-known artists of his generation.

It wasn't always this way. Back in 2003, when I first met KAWS—I was meant to write a catalog essay for a gallery show in Los Angeles that never happened—he was a working artist, arguably successful by most metrics but somewhat derisively labeled a “street artist” while, ironically, finding his interest in doing street works on the wane.

“The vibe in New York got weird post-9/11,” he tells me now. “In 2002 you weren't trying to break into bus shelters. Everybody was on edge and alert. ‘Who is this guy with a wrench taking apart this phone booth?’ ”

Leaving behind street work was a significant departure. KAWS had elicited attention in the early '90s throwing up traditional graffiti-style “KAWS” tags—a name that simply struck Donnelly as visually appealing; it has no hidden meaning—on billboards around Jersey City. “You're totally thinking how to have a visual impact,” he says. “And making stuff that's a quick read. You're competing against thousands of kids, and you learn from people who have done it before you.” There were inherently elevated stakes developing one's practice in the streets: You had to stand out against everything else in the cityscape.

After barely graduating high school, Donnelly cobbled together a portfolio and eventually gained entrance to the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan and, upon graduation, secured entry-level work doing illustrations for an animation company. It was at this point, in response to the change in his everyday terrain, that Donnelly's interests shifted. He had a new canvas, so to speak. “In Jersey City there were billboards everywhere, so that's what I painted on,” he says. “But once I got to the city, it became more about bus shelters and phone booths.”

More specifically, it became about the artist's “interruptions”—sly subversions of ads for hot brands like Calvin Klein or Guess, to which the artist festooned his Bendy character, a mischievous serpentine being he'd entwine around a Kate Moss or Christy Turlington. Because of their placement in downtown NYC and SoHo, the works were clocked by his growing number of fans—and were often stolen for resale. Eventually, KAWS began to sour on the operation: “When I first started doing the interruptions, they'd last like two months. At the time, I was working as an illustrator for Jumbo Pictures, and I'd mostly install them along my trail to work. But it got to the point where the pieces would last for like a half day. I'd go back to document them, and there would just be a pile of glass on the ground where I'd just installed the piece. I was like, ‘What's the point? They're just ending up on eBay or whatever.’ ”

The upside to the eBay heat was that the works traveled far and wide. Among the particularly fervent early admirers was an influential cadre of designers and tastemakers in Japan, including Nigo of A Bathing Ape, Hikaru Iwanaga of Bounty Hunter, Jun Takahashi of Undercover, and Medicom's Akashi “Ryu” Tatsuhiko. Donnelly, in turn, made frequent sojourns to their shores, where he developed an unlikely creative outlet. In collaboration with Bounty Hunter and Hectic, KAWS designed his first-edition “toy” in 1999. The first release, an eight-inch-tall version of the aforementioned Companion, which originally sold for $99, was followed by the release of the artist's next character, Accomplice, a slightly out-of-shape-looking Pink Panther doppelgänger with a Companion skull-head and a set of pert bunny ears. As the figures began reselling for thousands, their massive popularity began to lay the groundwork for the artist's zealous fan base.

Meanwhile, KAWS was making his earliest inroads into the gallery world. First, in 1999, with tastemaker extraordinaire Sarah Andelman at her seminal Paris boutique, Colette, and then at Parco Gallery in Tokyo. The 2001 Parco Gallery show featured two bodies of work. The first included black-and-white panels derived by abstracting imagery sampled from Chum, another character. The second was a series of colorful “landscape paintings,” which looked like tripped-out Ellsworth Kellys made from vast swaths of electric color and shards of Simpsons characters' heads. At the time, KAWS's decision to work in Japan was a pragmatic one, based on demand and the openness to his art there. But he recalls coming up against some wariness back home: “People were like, ‘Why are you doing all this stuff in Japan that nobody sees?’ I was going where the work and opportunity was. And when the energy started moving over that way [Asia], I was like 10 years in already.”

But the gallery success remained somewhat muted—there just wasn't the same sort of interest and energy as KAWS found in his other pursuits. In 2006, KAWS's established relationship with Medicom proved fortuitous once again when he partnered with the brand on his very own retail space in Tokyo, OriginalFake, which showcased his toys and OriginalFake streetwear. “Instead of playing the gallery game,” says Damon Way, who cofounded DC Shoes and approached KAWS about designing a sneaker at a time when artist-sneaker collabs were pretty much nonexistent, “he had all these sorts of proxies of influencers of culture in Japan that gave him so much lift and allowed him to avoid it.”

Having a brick-and-mortar operation gave KAWS his very own laboratory to beta-test ideas that struck his fancy. “I started OriginalFake because, in 2006, I decided not to care about galleries at all, not to give a shit, let the chips fall where they may,” he says, thinking back on his off-road adventure into the unconventional. “I was doing a completely commercial venture, a brand, a store. I designed everything, which was a lot of work, but when you work in all these different ways, you meet people, and that's ultimately what creates other opportunities, and so, ironically, that's when things started opening up.”

“He has a different system now, slightly more civilized,” Shepard Fairey says. “But that desire to be king of the concrete jungle is still in him.”

Another early KAWS über-patron was Pharrell, who first clocked some paintings at Nigo's place and began commissioning works, which ultimately led KAWS to his most significant gallery representation to date. To hear KAWS tell the story, it was a highly unexpected pivot. One day, out of the blue, he got a cold call from Pharrell, who reported that he was with his buddy, French art dealer Emmanuel Perrotin, who shows art-world heavy hitters Maurizio Catalan and Takashi Murakami and mounted the first commercial show of Damien Hirst.

“It was pretty awkward,” KAWS says, laughing as he recalls the moment. “Pharrell was like, ‘You gotta talk to my friend Emmanuel—he's sitting right here beside me, surrounded by your paintings!’ And then he just sort of jammed the phone into Emmanuel's hands.”

The call paved the way for a lunch in Miami, organized by Sarah Andelman, who had showed the artist before anyone else and was also a friend of Perrotin's. “I met Brian and I realized the force of the man,” remembers Paris-based Perrotin, who first showed KAWS at his (now defunct) Miami gallery in 2008 and currently maintains no fewer than seven galleries worldwide. “At the beginning of the career of an artist, you have to feel the potential. And I was immediately very impressed by the vision Brian had to move the work to another level, which is one of the aspects that's very difficult for an art dealer. You see what has been done in the past, but you always take the risk that the new series of work might disappoint you. And it was one of those nice moments where the artist showed a great evolution.”

That first Perrotin show, Saturated, sold out before the opening. It consisted of significant-feeling panels packed with twisted-up and cropped SpongeBob-like visages, as well as other very pastoral-inspired canvases featuring KAWS's “Kurfs” (as in Smurfs) characters. Evident in the show was a leap in scale, a growing confidence and complexity of composition, as well as the luxurious sense of color referenced in the title. A cursory Google of the show reveals the always present schism that surrounds KAWS—some hailing him as the heir apparent to the pop throne, others accusing him of any number of art crimes, including being a lazy appropriator, a glorified toymaker, or a once monumental graffiti artist who “fell off” the day he dipped his toe into the white cube.

Both criticism and accolades aside, what was undeniable was that the guy with the second-lowest GPA in his high school, who'd been told by a college guidance counselor not to bother even applying to schools, had been working nonstop and developed an arsenal of skills that, in turn, enabled him to answer in spades when the blue-chip galleries finally came calling.

It would be nearly libelous to say that after that first Perrotin show in Miami in 2008, “things really took off for KAWS.” More like Donnelly was shot out of a cannon with bells on and one of those batting helmets with beer holsters and tubes running directly to the mouth. And though the complete list is much too long, let's take a stroll through a few noteworthy highlights from the past decade: There was a sexy and slightly dangerous-looking woman's “chomper”-toothed shoe for Marc Jacobs; a pair of Dos Equis beer bottles reengineered with the artist's signature “XX”; a reimagined MTV “Moonman” award; and lastly—and a personal fave—a 40-foot-tall floating Companion for the 2012 Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, which soldiered through the entire event covering his eyes. Along the way, there were several more shows with Emmanuel Perrotin in various other locations; shows at Honor Fraser, in Los Angeles, which drew previously unseen blocks-long lines down La Cienega; and more recently, a burgeoning alliance with New York-based gallerist Per Skarstedt, who made his mark trafficking in the most extreme altitudes of “blue chip,” including the likes of Picasso, de Kooning, Warhol, Martin Kippenberger, Christopher Wool, and Richard Prince.

Needless to say, KAWS has come a long way from his first billboard in New Jersey. And in recent years, he has gradually become associated with the handful of artists who initially made their names on forms not traditionally embraced by the high-art world—graffiti and street art—but then went on to become globally recognized. A lineage that includes Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Banksy, Shepard Fairey, and now KAWS.

There is a unique expectation that attaches itself to all contemporary artists, but street artists in particular, whose work can convey the possibility of mass production. (Think of Haring's ecstatic, celebratory characters or Fairey's posters.) And so, having garnered worldwide acclaim, a vigorous demand soon follows. No sooner does an artist “hit” than he finds himself in the enviable yet very real predicament of trying to meet the crushing demand for new work that major success generates. Not only must the artist execute fresh and compelling work at a greatly quickened pace, but he must also continually serve highbrow, high-net-worth collectors the iconic offerings that launched him into the stratosphere to begin with. And if the artist can somehow manage to traverse that fire walk, he must then churn out work without ever giving off the perception of flooding the marketplace.

Of his business-and-execution strategy, Donnelly says, “I feel like you have to be just as creative on that side as you do making the work. But it's not an overnight thing.”

Adds Fairey, who's known KAWS since the '90s and has firsthand experience as an artist with global reach: “People have this image of the artist working by candlelight when the inspiration hits. But in truth, there's much more to it and it takes a long time to get it all working. There's really this very real kind of almost blue-collar aspect to it, which I've always embraced, [as has] Brian, who I know works incredibly hard.”

“Step by step, you figure out how to get things made,” Donnelly says. “I've always been sort of a hustler and believe in getting it done any way you can.”

Not long after the Alone Again opening in Detroit, I catch back up with KAWS at his studio in Brooklyn's Williamsburg neighborhood. As usual, Donnelly is dressed casually, in some version of chinos, a solid crewneck, and his ever present dark cap. Despite yet another round of auction results yielding a $5.9 million sale, as well as some 3's and 2's for good measure, his low-key demeanor is fully intact.

Though obviously very aware of the current mania, KAWS keeps the auction record at bay as best he can. “It's there,” Donnelly says. “It exists. But you look at so many artists over the years and you realize you can't get super psyched when it's high and you can't get too down when it's not. All you can do, really, is just keep trying to figure out how to make the things you want to make. ‘Successful’ is when the picture's finished, not when you sell it at your gallery. Or if it trades hands. And anyways, a lot of the [paintings at auction] are, like, 10 years old.”

I suggest that maybe the fact that the works selling are kind of “old news”—to him, at least—might actually help to somewhat abstract the impact.

“If it was something I had just made, that would probably put me more on edge,” he concedes.

Another factor likely to be preventing KAWS from dwelling too much on auction results is the flood of incoming requests and immediate commitments. By the time the clock strikes 12 on December 31, KAWS will have released his latest collaboration with Uniqlo, mounted two more museum shows—one at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and another at the Qatar Museum in Doha—and announced a 2021 survey at the Brooklyn Museum, supercharged by the fact that it's taking place on the artist's adopted home turf.

The first floor of KAWS's studio is a somewhat narrow corridor of active working space lined with a new series of paintings. What strikes me right away about the studio—both now and when I first visited, back in 2003—is the nearly pristine nature of the space. As opposed to most studios I visit, Studio KAWS could easily be converted into a private surgery facility if need be, every paint and brush in its proper place.

Though they're mostly in their beginning stages and don't have much paint on them, the canvases are quite large and bear a definite resemblance—even in their embryonic outline/layout state—to the ones I saw in Detroit. Abstract shapes extracted from larger, predominantly figurative-seeming imagery, likely derived from the artist's earlier more cartoon-inspired work, blend against other more amorphous-seeming shapes. The sense of continuity is already quite evident, though I'd be willing to wager that by the time these paintings are finished, the source imagery will feel much more deconstructed. It's almost as though a bunch of figurative elements have been blown to smithereens, then used as formal, compositional building blocks.

Upstairs in the studio we sit on a green couch, the very same couch that pops up often on his Instagram alongside famous guests. As we settle in, I press for a deeper look into the process, a glimpse behind the wizard's curtain.

He tells me that he works out most of his paintings on a computer, though he will still occasionally work bits out on paper, as with THE KAWS ALBUM, which exists entirely in paper form somewhere deep within the catacombs of his studios and storage spaces. He adds that he'll still always “leave some room for spontaneity.”

Which I take to mean not literally, as in leave open space and unconsidered areas on the canvas, but staying open to the idea that adjustments and additions might be needed. “Exactly,” Donnelly says. “I guess I mean ‘open’ for me, which isn't exactly all that wild.”

To further illustrate, Donnelly references the massive wall piece from Detroit, which, he says, felt “like it still needed something the first time it was executed.” So he went back to work on the computer and came up with what is now the top layer of the painting: an asymmetrical mesh-like black, which he felt resolved the piece. Armed with the artist's words as present-tense wisdom and thinking back on the wall piece, I can see how, beyond the behemoth scope and visceral impact of that candy-colored 62-foot-long, 12-foot-high wall, it is the black overlayer that acts to both contain the piece and add a sense of cohesion, while, at the same time, obscure areas, which adds a certain sense of mystery.

When I convey my impressions of the paintings to Shepard Fairey, he is quick to confirm and expound upon Donnelly's growth and steady, nuanced evolution over the past few decades. “I mean, where Brian is right now,” Fairey says, “with the strength of his color theory and the abstraction, and having a connection to a sort of trompe l'oeil where the three-dimensional space is being suggested but, at the same time, if you choose not to see it that way, you can also read it as a flat abstraction—it's very sophisticated.”

Working primarily in acrylic, which dries more quickly than oil, KAWS explains that after he decides on a color for a section of a painting, he then lays down just a dot of paint in the area, literally creating a kind of coded guide on the canvas, which, in turn, enables him to put down or pick up other work without the danger of losing continuity. “I usually always have a bunch of things going on at once,” Donnelly says. “Some things kind of make their way to the foreground, while others might sort of taper off.” As for the sculptural side of his practice, the evolution is made much more evident by materials used—from vinyl to bronze, then wood—and scale, which started off in inches with the “toys” and has now shot past a hundred feet in height, with the “inflatables” that tend to dominate the Insta-Universe whenever and wherever they next appear.

When I'd initially reached out to Donnelly about writing this piece, I sent an email, not wanting to be too intrusive or presumptuous. But eventually, after not hearing back, I eschewed professional distance, sent a text, and immediately got a response. When I mentioned this, Donnelly promptly fired back a screen grab of his 143,000-plus unread emails. Given the current frenzy over his work, one can only imagine the endless litany of requests, a few of which I guess out loud might be notably absurd, prompting Donnelly's largest grin of the afternoon. “You're talking about, like, 80 percent of them. I mean, I try to always be very careful about the [commercial] associations I'd align with my characters, as if they were somebody in my family.”

The sentiment prompts me to recall how, even at our 2003 meeting, at a very different juncture of his career, KAWS possessed the ability to turn down opportunities, which isn't always easy to do early on: “Yeah, I've always been able to say no,” he says, nodding thoughtfully. “And for the most part, I have always been lucky to be in a position to do so. You have to really think things through and understand the time and energy you're going to end up devoting to a project.”

Given as much, I ask which collaborations stand out as more organically aligned. “The Dos Equis job was kind of a no-brainer,” he says, lighting back up. “I mean, a beer brand called Two X's?” The 2010 Dos Equis beer campaign involved not only two KAWS-engineered bottles—green and amber—generously adorned with the artist's XX's but, also, a massive, many-storied billboard in Mexico City. Conversely, a 2017 collaboration on a signature Air Jordan 4 yields some less blissful memories. “Those sneakerheads are insane,” he says. “You wouldn't believe some of the emails I got from kids who didn't get a pair. Abso-lutely vicious.”

With our session in Williamsburg winding down, I decide to test the bounds of my host's patience one last time, divulging that I'd received a Deep Throat-style tip that, back in his early animation/illustrator days, Donnelly sometimes layered “subversive imagery” into his backgrounds. I ask him to either deny or confirm, and if yes, then to please further illuminate what might possibly constitute “subversive imagery.”

“I don't know what you're talking about…,” he says, suppressing a smile. “It's been such a long time.…”

He leaves me with a faintly limned Cheshire grin as I step out onto the street. The exchange about his playful early tactics was a good reminder that KAWS took root in the real world, lawless and in Technicolor, initially driven, like most artists who first cut their teeth on buildings, billboards, and bridges, by a burning compulsion to declare one's existence, even if it means risking jail time or, worse, actual death.

A few days later, speaking with Shepard Fairey, I suggest that KAWS's early days in the streets going big and competing against everything in the skyline must've prepared the artist well for his inevitable leap to the vast canvas of contemporary art. “Brian's always looking for ways to create something that's going to connect with people,” Fairey says. “He has a different system now, slightly more civilized. But that desire to be king of the concrete jungle is still in him.”

Arty Nelson is an art, food, and television writer living in Los Angeles.

A version of this story originally appeared in the August 2019 issue with the title "Generation XX."

Originally Appeared on GQ