The UK crisis no one is talking about in this election

The day before Boris Johnson launched the Conservatives’ election campaign, the prime minister received an unwelcome reminder of a pledge in his party’s 2015 manifesto.

A watchdog revealed not a single one of 200,000 ‘starter homes’ promised four years earlier had been built.

Tackling Britain’s housing crisis appears to be one of many casualties of Brexit. But it has been more strangely absent from recent political debate even than other key issues struggling for attention, from the NHS to crime.

READ MORE: Lib Dems struggle to break through in Remain heartland Cambridge

Housing is not even mentioned among Conservative priorities on their website’s ‘manifesto’ page, and their plans are only set out from page 29 of the document itself.

Labour and the Liberal Democrats have unveiled more radical promises. But it went unmentioned in Lib Dem leader Jo Swinson’s manifesto launch speech, and Labour has still dedicated only a few days of the campaign to housing.

Rising prices, rents and rough sleeping

Embarrassment about a growing problem on their watch may also be behind the Conservatives’ relative silence.

“If you walk from the station into the centre early evening, you’ll see lots of people sleeping in shop doorways. We didn’t have this problem eight years ago.”

Daniel Zeichner was talking about Cambridge, but the Labour election candidate could have been talking about many towns and cities across Britain.

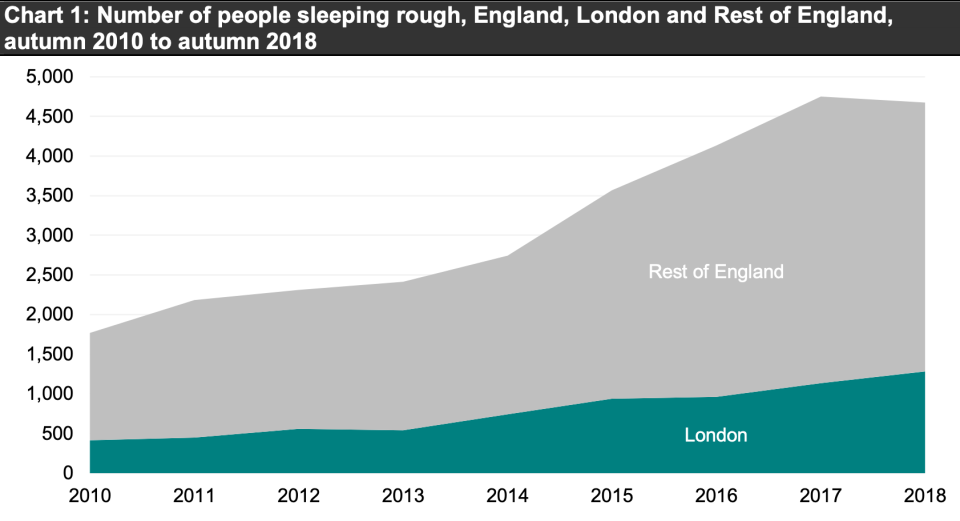

Official figures suggest rough sleeping has soared by 165% in England over the past decade, while around 1.1m families are on social housing waiting lists.

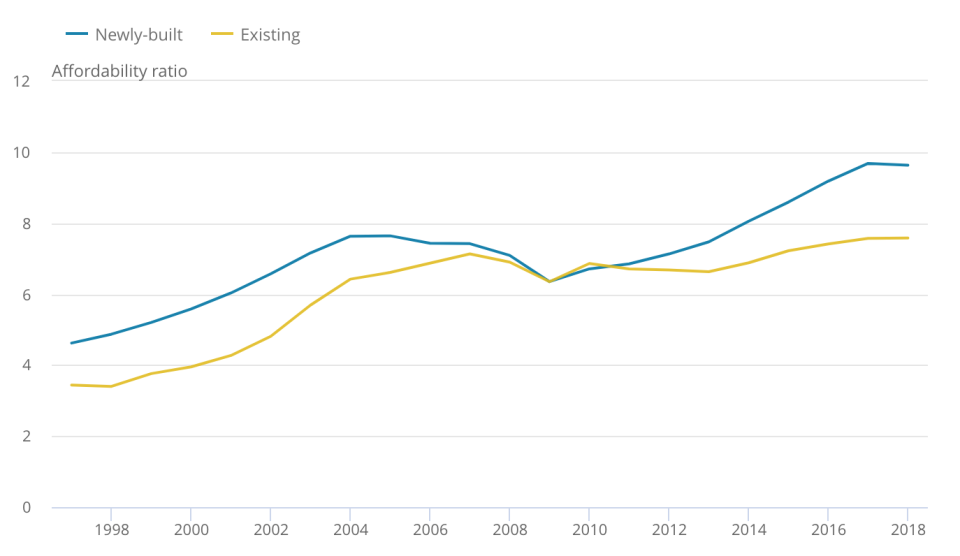

Rents have kept increasing and housing affordability, which compares wages to property prices, has worsened for much of the past five years. Earnings have not kept pace as properties have doubled in value since 2002, despite a recent slowdown.

The darker side of economic success

London’s sky-high prices, rising rents and gentrification often spark controversy.

But such problems are not limited to Britain’s capital, and all too rarely spark deeper conversations about the dangers of poorly managed economic growth.

Such challenges can be particularly severe in dynamic cities with fast-growing economies and populations, with not only housing but also local services sometimes failing to keep pace with soaring demand.

They suggest economic success can come at a cost, and should perhaps spark tough election questions about avoiding unwanted side-effects. But while Brexit has sparked more concern about helping struggling places to thrive, national politicians rarely debate how thriving places can still struggle with the darker side of success.

READ MORE: What the general election could mean for jobs in the UK

Cities like Cambridge should provide a wake-up call. Its tech and science-dominated economy is booming, and it boasts a world-famous university. But interviews and research by Yahoo Finance UK highlight the strain growth has put on housing, local infrastructure and even future success.

As one local parent has asked: “Why should residents...be delighted that AstraZeneca has moved in, if it means their children can no longer afford to live in the area?”

Not just a London problem

Even the Conservatives’ candidate Russell Perrin has said he could not afford to live in Cambridge, now Britain’s priciest city outside London. Average property prices have soared to £430,000 ($558,652)—almost 13 times higher than average local incomes, up from 4.4 times two decades ago.

Guillermo Cobos, 47, who runs a local Spanish street food truck, said he feared he’d be too old to get a mortgage when he and his wife eventually saved enough for a deposit. “To buy in Cambridge is so difficult. We had to live out of Cambridge, and pay rent all our lives.”

Zeichner said that as well as increased rough sleeping, he’d seen renters “ripped off constantly” in his four years as local MP, suggesting landlords exploited high demand by using six-month lets to regularly hike prices.

READ MORE: The UK cities where property prices are rising fastest

Charlotte Westgarth, 24, said she and her partner had also moved six miles north to avoid high rents. “We were in a [central] one-bed, but it was so tiny. For £950 a month, that’s not worth it.”

A growth in commuters forced to live further out has also put pressure on local transport. “Journeys that should take 15 minutes can take 90,” said Zeichner. Local authorities warn morning city traffic could soar by 30% and car journey times double in surrounding south Cambridgeshire by 2031.

Tech giants and tent cities

But given the tent cities and housing crisis on a starker scale around Silicon Valley, rising costs and rough sleeping should perhaps be no surprise in a UK city sometimes called ‘Silicon Fen.’

“High prices are fuelled by high demand, which itself is fuelled by the strength of the local economy and in-migration of highly skilled workers,” a recent local council report noted.

Now one of Europe’s biggest tech clusters, Cambridge has been a major British success story in recent years, rebounding and expanding rapidly since the financial crisis while much of the UK has struggled.

Employment has boomed in the kind of high-skilled, high-paid tech and science jobs politicians often paint as a model future and pledge to deliver.

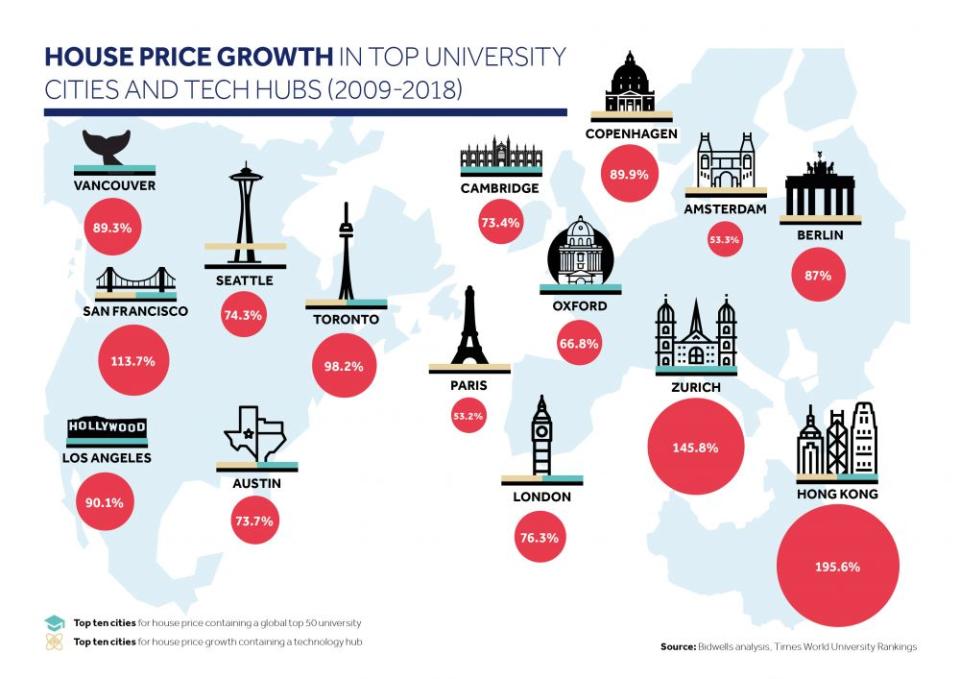

Research by Cambridge-based consultants Bidwells highlights this link between the “scramble for space” among housing costs and the tech boom. It suggested prices in global tech hubs like Cambridge are 20% above wider local averages.

Rough sleepers may be a familiar sight nearer to town, but many visitors’ first sight after leaving the station is the sleek new office blocks that now house Microsoft (MSFT), Apple (AAPL), Amazon (AMZN), and WeWork.

“Alexa lives up Station Road, and Siri lives at the bottom,” laughed Matthew Bullock, co-founder of business research body Cambridge Ahead, with the city a hub for voice recognition software.

That boom has contributed significantly to wider UK growth and tax receipts, and nourished other supporting industries, from law firms to Cobos’ street food truck, which serves tech workers at the Cambridge Science Park.

How housing and infrastructure failed to keep up with demand

But the boom has also pushed up prices and pushed out some locals, as housing, transport, health and other provisions are widely seen to have failed to keep pace.

If demand is one side of the story, supply is the other. Local authorities recognise a shortage of affordable homes close to workplaces is central to Cambridge’s house price boom.

“Infrastructure and public services are not being laid down at a rate that keeps up with employment growth,” said Bullock.

Planning rules, developers, slow-moving government, and former prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s opening up council housing to private buyers are just a few of the many factors that are sometimes blamed for historic under-supply. But Cambridge Ahead’s meticulous firm-by-firm research in Cambridge highlights a major lesser-known problem — poor data.

Local planning for homes, roads, healthcare and other provision around Cambridge has been based on “much lower growth than actually achieved,” according to Bullock. He said a striking gap between Cambridge Ahead’s figures and official figures indicated local bodies’ employment forecasts were “significant” under-estimates.

“All government provision is based on this. It results in not enough houses being built, prices going up, people moving out and more congestion,” he added.

Bullock said he hoped the better data would help not just Cambridge but also national statisticians, and in turn help authorities across Britain ensure housing, schools and other provision meet demand. “It’s changed the whole debate,” he added.

The parties’ promises to fix the housing crisis

The major parties have all promised to increase housebuilding this election. The Conservatives and Lib Dems promise 300,000 homes a year by the mid-2020s, while Labour propose 150,000 council and affordable homes a year.

The Conservatives also promise mortgages with 5% deposits and discounts for local first-time buyers, while Labour would control rents and order developers to make more properties affordable. Cambridge Lib Dem candidate Rod Cantrill wants a cheaper ‘living rent’ for key workers.

But governments of all colours have a poor record of chronic under-supply dating back decades. More local players are increasingly taking the initiative in expensive areas.

Cambridge’s Labour-run city council is trying to build 1,500 council homes. It is also piloting a radical scheme to help rough sleepers called ‘Housing First’ alongside the Conservative-run county council.

New developments are springing up, rail, bus and cycle routes have been expanded, and the government has devolved powers and cash to a new regional Conservative mayor—who even wants a metro system.

READ MORE: The main parties’ promises on housing this election

Meanwhile Cambridge University chiefs believe it is unique among universities globally after starting to build a “whole new area” of Cambridge. The largest capital project in its history, Eddington will provide housing for thousands of staff as well as post-grad students.

How the housing crisis threatens the economy

The university’s unusual intervention highlights how the housing crisis also hurts UK employers, even threatening the growth that fuelled demand in the first place.

“Most employers say their biggest problem is recruitment and retention,” said Zeichner.

He said unaffordable homes and long commutes made it harder to attract global talent to firms like Astra Zeneca, which moved its HQ to Cambridge in 2016. “If you’re trying to choose between here or the [San Francisco] Bay Area, that can be enough.”

He said local schools were also key for potential recruits. But his Lib Dem rival Cantrill agreed affordability also threatened standards: “Teachers are voting with their feet, as they can’t afford to live in the city.”

Meanwhile such firms also need “cleaners, caterers and caretakers,” Zeichner added. But a local expert report said last year “the damage to society from the continuing drift away of less well-paid workers may become irreparable.”

The report suggested such challenges risked choking off growth. “We are rapidly approaching the point where even high-value businesses may decide being based in Cambridge is no longer attractive.”

Zeichner agreed it threatened future investment, noting: “This idea Cambridge’s success is assured is a mistake. Success only happens if you make the right decisions.”

Bullock, who contributed to the report, said inadequate infrastructure was an even greater threat than Brexit, which also spooks the city’s tech and science firms.

But unless housing and handling growth swiftly climb up the political agenda after Brexit, cities like Cambridge may have to solve such problems on their own.

The alternative could be stark, as the report warned: “Cambridge is at a decisive moment in its history where it must choose whether it wants to once again reshape itself for growth, or let itself stagnate and potentially wither.”