Will Gazillionaires Gentrify the Galaxy?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Around a decade ago the Danish architect Bjarke Ingels had an epiphany.

His firm, Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), already enjoyed a reputation for gutsy, boundary-pushing, borderline sci-fi projects when it was recruited to work on the Virgin Hyperloop, a cutting-edge transportation system made up of frictionless vacuum tubes that enable passenger pods to zoom at absurdly high speeds. He was fascinated by the speculative fiction of Philip K. Dick and William Gibson, the groundbreaking writings of aerospace engineer Robert Zubrin, and the innovative work being done at the Hawthorne, California, headquarters of Elon Musk’s SpaceX. Then a meeting with the acclaimed science fiction novelist Kim Stanley Robinson, known for his Mars trilogy, electrified the architect’s imagination.

“He doesn’t use the term science fiction,” Ingels says of Robinson. “He uses the term future history.”

Thus began Ingels’s journey into the space age realm of lunar and Martian habitats. Today he’s no longer alone. The amount of investment, innovation, and media attention surrounding commercial space travel and such companies as SpaceX, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin is creating a new frontier in architecture (with other firms, like Foster + Partners, also leading the way) and perhaps soon even interplanetary real estate deals. The future, as the oft quoted saying goes, may already be here, and the masters of the universe are living up to their name by engaging in a new sort of space race. We’re not talking Jetsons or Trekkies here. The entire world space economy was valued at a staggering $424 billion last year, according to the firm Euroconsult.

“I have spoken to multiple global real estate developers who all want to be the first developer on the moon,” says Melodie Yashar, vice president of building design and performance at Icon, a 3D-printed construction startup in Texas that works with Ingels’s firm on lunar building concepts. “The first person to get there is probably going to be the first person who can build it. It’s kind of like, ‘Build it and they will come.’ ”

From Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey to Dune and the latest Avatar flick, popular culture overflows with far-out images of building interiors on other celestial bodies. But they never quite reflect the mundane reality of grappling with the harsh elements of the solar system, not to mention the pragmatic work of risk-averse space engineers and scientists. The International Space Station “could be considered the cathedral of the 21st century,” says Michael Morris, a founding partner of the architecture firm SEArch+. But it’s not exactly a looker. Nor is it meant to be. Its network of wires, cables, and exposed tubes is intended to protect, not to wow. “Its design is very uninspiring.”

Lunar architecture is likely to evolve alongside improvements to living accommodations there, beginning crudely but over time morphing into something more sophisticated, slick, even Kubrickian. An “extended stay” on the moon is expected within a decade and permanent habitats in roughly 50 years, with people living on Mars a few decades beyond that, says Haym Benaroya, an aerospace engineering professor at Rutgers University. “Maybe the evolution of staying on the moon will grow slowly. First for a week, then for three months, then for a year at a time. And eventually the infrastructure will evolve to a point where you have a small city with dozens and dozens of buildings.”

Ingels is gearing up for that moment. Over the 18-year history of his practice, his firm has generated headlines for its out-of-sight structures, such as the tetrahedral Via 57 “courtscraper” residential building on Manhattan’s West Side and the ski slope–topped Amager Bakke power plant in Copenhagen. Going to infinity and beyond was a natural next step, and the Hyperloop venture proved to be a turning point.

“I came up with this idea that BIG should be about giving form to the future,” he says. “That somehow we are the midwives of the future.”

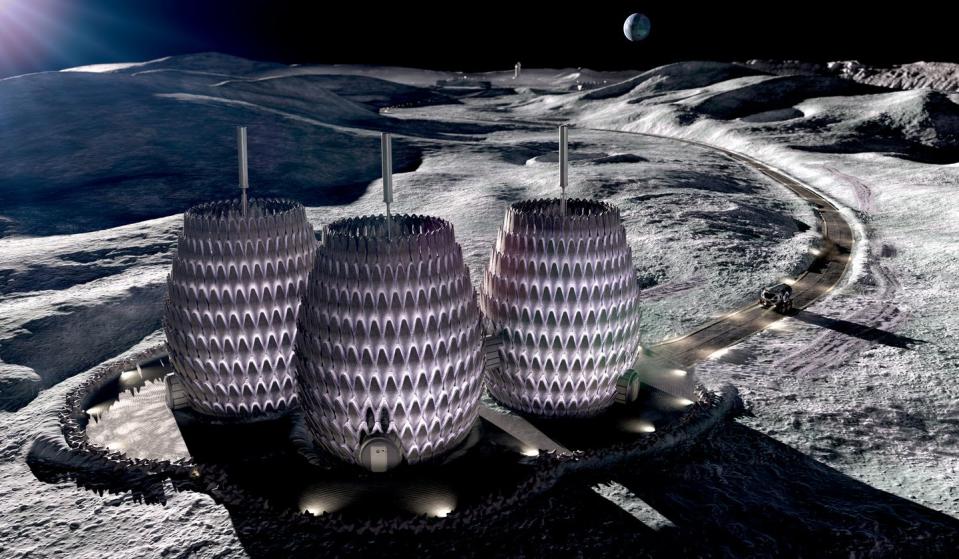

The United Arab Emirates is one of the Hyperloop’s backers, and in 2017 its Ministry of Possibilities asked the architect to imagine what a town of a thousand people on Mars in 2117 could look like. The invitation eventually led in a roundabout way to a formal introduction to Jason Ballard, Icon’s swashbuckling chief executive, who in 2020 launched Project Olympus with BIG, an audacious plan to build moon structures as part of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Artemis program. The two space cowboys’ proposal? To construct, via 3D-printing machines, a cavelike, donut-shaped lunar base out of moon dust that shields its occupants against such lunar factors as radiation, micrometeorites, temperature extremes, and low gravity.

A year later the partners expanded on this “off-world” work with the Mars Dune Alpha, a 1,700-square-foot 3D-printed structure for NASA that simulates a habitat that supports “long-duration, exploration class” missions. Comprising four private rooms for the crew, an aquaponic vegetable garden, workstations, lounges, and even a gym, it proposes a way for humans to live on the frigid planet.

Though founded just five years ago, Icon has already raised more than $451 million in funding and last fall landed a $57.2 million contract from NASA for developing Project Olympus further. The money and interest in 3D-printing technology appears to keep pouring in. During a recent visit to BIG’s U.S. headquarters in Brooklyn, Ingels excitedly walked me around two tables covered in models of the Olympus work, as well as the firm’s various here-on-Earth efforts with Icon: a performance pavilion; a home design for the world’s first 3D-printed neighborhood, a 100-house development that’s currently underway in Georgetown, Texas, for the homebuilder Lennar; affordable housing structures; and an office complex. In a way, these terrestrial projects are partly a means toward interstellar ends.

It appears others are following suit. Foster + Partners, the firm behind the billowing Spaceport America campus for Virgin Galactic in New Mexico, began developing 3D-printed constructions for the moon with the European Space Agency in 2012 and for Mars with NASA in 2015. SEArch+ too has been dreaming up various proposals and won the NASA competition by collaborating with another firm, the New York–based Clouds AO, on the Mars Ice House.

While other architectural options, such as pressure vessels and inflatables, are also being floated, 3D-printing technology appears to be the most promising path forward. Even so, its viability remains questionable. “I hope they succeed,” Benaroya says of Icon. “But obviously there are issues with 3D printing on the moon at this point because of the required infrastructure to be able to do that.” Plus, he adds, moon dust is “extremely carcinogenic. It sticks to everything.”

Still, it’s not difficult to imagine that gated developments with billionaire pieds-à-terre may one day emerge, paid for by those aboard SpaceX and Blue Origin vessels, or by those companies’ owners. When I ask Benaroya if he envisions Musk and Bezos constructing their own moon mansions, he doesn’t miss a beat: “I could see it. They have enough money to do it, let’s put it that way.”

Morris, of SEArch+, credits Musk for “making space sexy again,” but he doesn’t see him building a moon McMansion anytime soon. “Elon, for sure, is very interested in rocketry, and in getting people to pay him to get them there and back,” he says. “But I don’t think he’s investing in, or really interested in, housing.” Should Musk or Bezos wish to build a cosmic compound, though, Morris has a design at the ready: the hivelike Lunar Lantern, a tiered, arched, three-level construction. “The first building on the moon should aspire to be iconic,” he says. “It should be akin to the pyramids or the Roman Forum. It should aspire to be something that has the lasting vision of man.”

When I mention to Ingels the notion of a palatial manse staring down from above at us little earthlings, he becomes animated. “I love the idea,” he says, then offers up an impassioned explanation, in the vein of author Yuval Noah Harari’s best-selling historical romp Sapiens, of the evolving concept of shelter over generations, from its primal protective purpose to its latter-day aesthetic pleasures.

Mars Trilogy

amazon.com

“Try to spend a night in upstate New York in January without a nice coat and boots or without a house—it’s gonna suck,” he says. “We’re already comfortably living in a world where we’re fully sustained by fire, by wearables, and by our built environment. Without these, we would perish. This is even more true on the moon and Mars.”

Ingels is especially bullish about the immediate progressive impact all this research and development can have right here on Earth, where leaps in 3D-printed construction can advance affordable housing solutions and hurricane-resistant home design. “The demands of building on the moon require certainty in terms of autonomy and precision,” he says. “In a way, by being capable of building on the moon, you become very good.”

Considered at a distance—from the heavens, as it were—the once radical idea of extraterrestrial lodgings doesn’t seem so far-fetched. In fact, it seems downright inevitable. If Ingels and Co. and Musk and his cohort have their way, it’s just a matter of time. The only question is, what counts as uptown when you’re hundreds of thousands of miles above 14th Street? Can you get Postmates up there? Well, beam ’em up, Scotty!

This story appears in the April 2023 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like