Garry Roberts was the glue that held The Boomtown Rats together

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

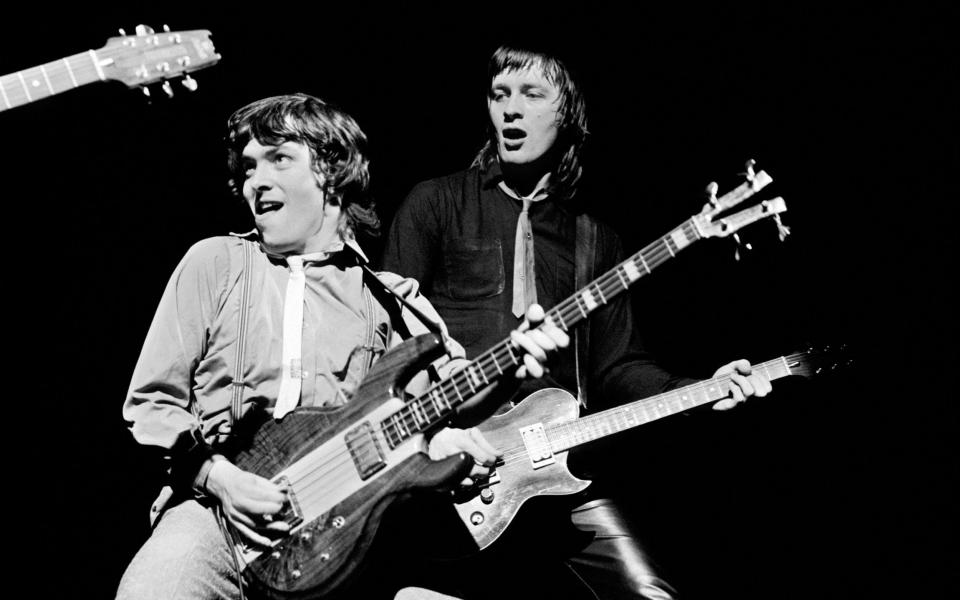

Garry Roberts of the Boomtown Rats has died, aged 72. Rock has lost another good one. “For fans he was The Legend,” the surviving band members wrote in a heartfelt statement. “For us, he was Gazzer, the guy who summed up the sense of who The Rats are.”

In a group publicly dominated by the big mouth, sharp elbows and high-wattage charisma of Sir Bob Geldof, Roberts may not have been a household name. But he was right at the centre of one of the greatest bands of the new wave era. “There was a lot of rocking going on that night” to quote the opening line of The Boomtown Rats’ 1978 number one smash, and it was Garry (with two R’s, from Garrick) who was doing the rocking, his sharp guitar playing, overdriven amps and rock’n’roll swagger helping drive the Rats all the way from heated up Irish pub rockers to international stardom.

It was Roberts who originally gathered five young musicians together in a pub in Dun Laoghaire, south Dublin, in spring of 1975, to form a band that would do far more than just become the first punks to score a UK number one single. They would go on to help transform their home country. And it was Roberts who was instrumental in their revival in recent years, convincing multi-millionaire businessman and activist Sir Bob that it was time to get back to his punk rock roots.

In recent times, The Boomtown Rats were in danger of becoming a footnote in rock history, almost totally eclipsed by the global fame of their frontman, reduced to just something Geldof did before Live Aid. Yet for a few years in the late Seventies, they had been the most interesting pop group in Britain and Ireland, scoring hit after hit with sharp-witted, punk inflected, new wave music, chock full of bright ideas, crammed with sparky hooks, and delivered in vivid, attention-grabbing style.

Between 1977 and 1980, The Rats had nine consecutive top 20 singles, including two quite extraordinary number ones. Rat Trap was a Springsteen-style shape-shifting five-minute soap operatic epic about the crushing pressures of working class life. It is an epic surpassed in their own canon by I Don’t Like Mondays, surely the only chart-topping pop song about a school shooting. The song gave them their only hit in the United States, where they were briefly touted as the next big thing before it was pulled from the radio, as programmers belatedly noticed what it was about.

The bold accompanying video was an early triumph of the pre-MTV era, casting the group as witnesses to an unfolding tragedy, the final shot featuring the Rats and a cast of school children watching the video itself. The Rats were one of the first bands to really understand and harness the power of this new visual medium, presenting themselves with a colourful comic exuberance, although often shot through with an abrasive edge of punky anger. They were never cute and cuddly, like Madness, and it was perhaps this spikiness which made them unpalatable in the long run.

There is something very shrill and in-your-face about The Rats’ run of hit singles, the aggressive selfishness of Lookin’ After No 1, the taut lechery of Mary Of The Fourth Form, the shrieking, sneering satire of She’s So Modern, even the mechanical alienation of Like Clockwork. As they became established fixtures of the charts, they tried to soften their sharp edges with thicker keyboard lines and Geldof’s voice lower in the mix. But that underlying abrasiveness is still present in the snarling paranoia of Always Someone Looking At You, the poisonous character study Diamond Smiles, and bitter sentiments of their last top 10 hit, 1980 reggae satire Banana Republic that mocked the parochial politics of their home country, and was banned in Ireland as a result.

This quality of aggressive, attention-demanding neediness certainly came from Geldof, the archetypal rock star with a chip on his shoulder. It was a crucial element in helping them break out of an Irish music scene characterised by a sense of inferiority and inadequacy. But the Rats were always a pack, and from the very beginning Roberts was a true believer in the notion that a group from Ireland could compete with the best. While Northern Ireland’s Van Morrison was a legend, and Thin Lizzy had made inroads, The Boomtown Rats were the first ever Irish band to reach number one in the UK.

The impact that had on their home country is impossible to understate. As someone growing up in Dublin in the Seventies, the Rats made you feel it was possible to escape the confines of what was then the poorest country in the European Union, and to demand to be treated as an equal by the cool cats at the centre of the pop culture world in England. It was the first lonely roar of the Celtic Tiger, and it opened the door for so many others. As U2 front man Bono has said, his own group rose up in “a post-Geldof world where you can hustle and hassle for a place at the top of the queue. It was climbing Mount Everest by helicopter.”

It may well be that Geldof’s talents for quick thinking, organisation, fearless promotion and passionate action were, in the end, better suited to other things. It is a little remembered fact that all of the Boomtown Rats play on The Band Aid single Do They Know it’s Christmas?. They were fully supportive of Geldof’s passionate charity endeavours. But the world-changing success of Live Aid propelled the frontman into a whole new area, and the group broke up the next year.

Afterwards, Roberts worked as a sound engineer before hanging up his guitar for over a decade. “When the band broke up,” Roberts has said, “I think I suffered from post traumatic stress disorder, and as a result I think I became intolerable. And then I had to pull myself together.” He worked as a life insurance salesman in Ireland, then (disillusioned with the business) qualified as a central heating operator. One can just imagine the bemused conversations as one of Ireland’s leading veteran rock stars turned up at households to fix faulty pipes.

But Roberts had also started playing again by the late Nineties, often with Rats drummer Simon Crowe, with whom he formed a formidable rhythm section. Always a rocker at heart, still sporting Elvis sideburns, a leather jacket and riding a motorcycle, Roberts “developed a plan to get the band back together.” In 2013, to his great joy, he succeeded, persuading Geldof and two other founding members (Crowe and bassist Pete Briquette) that it was time to do the Rat again.

They released a suitably trashy, punky new album in Citizens of Boomtown in 2020, and Roberts can be seen talking with pride about their revival in a punchy, moving documentary of the same name. I am in that documentary too, paying tribute to a band who really made an impact on my life. I spoke to Roberts after the cinema premiere in Dublin. He thanked me for the kind words. I thanked him for the amazing records, the glorious solos, and providing an inspiration to my whole Irish generation. He changed my life. I don’t really have enough kind words for that.

Anyone lucky enough to have caught one of their recent tours will understand why the Rats made the impact they did. I last saw them in the Palladium last year. For a bunch of grizzly old punks, they never once took their foot from the peddle, with Roberts swaggering about, blasting out guitar lines with fuzzed up joy.

It was clear the old gang had rediscovered the utter thrill of playing tautly drilled music with like-minded friends, and the loyal old crowd was on their feet from the beginning, singing along lustily, and generally behaving in ways that made the Palladium feel less like an august theatrical emporium than a dingy old basement club in 1977. There was a lot of rocking going on that night, to put it mildly. Bob Geldof self-mockingly introduced them as “the greatest rock and roll band in the world … from Dun Laoghaire.” That is a title no one is ever going to take away.