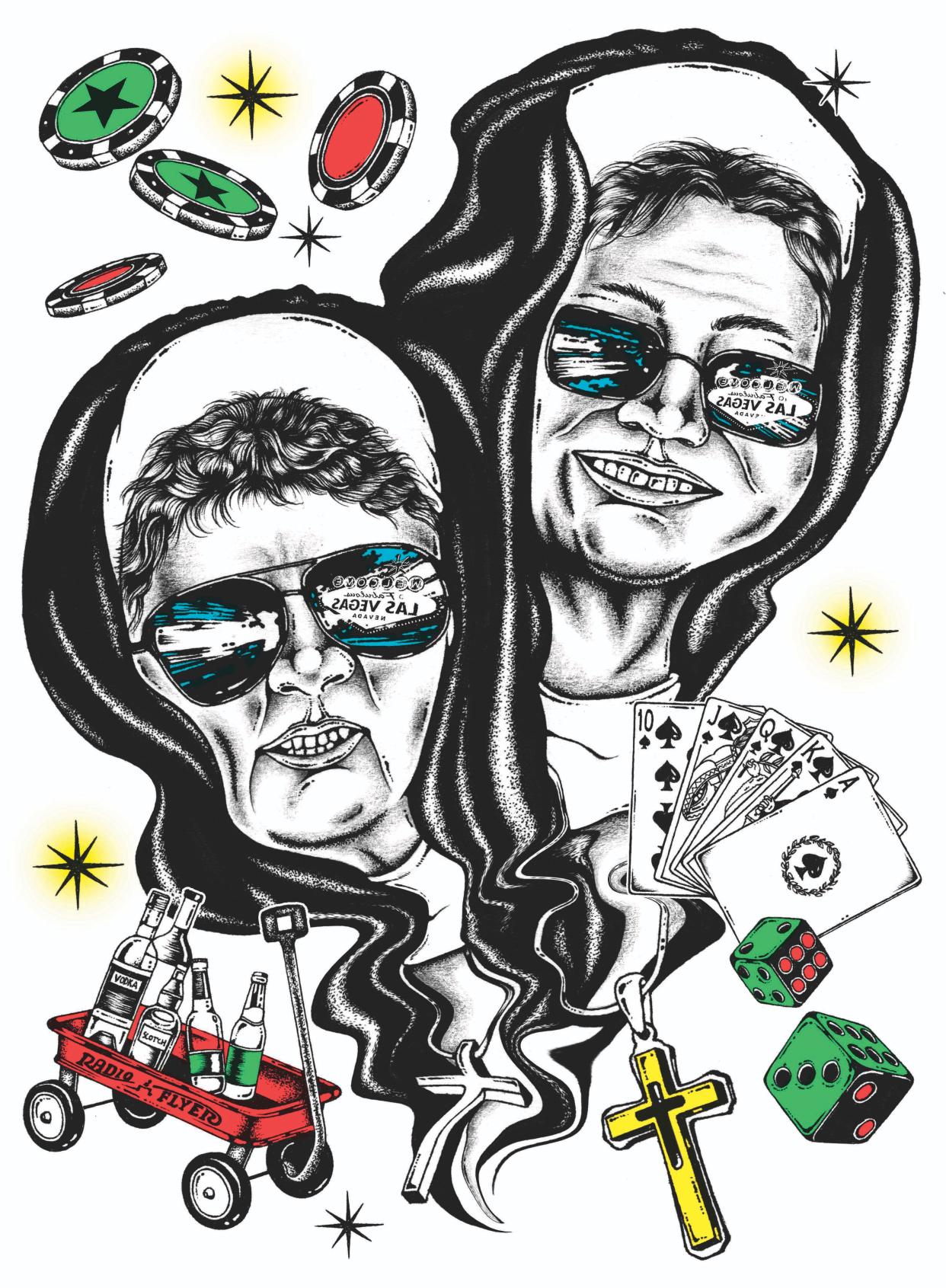

The Gambling Nuns of Torrance, California

The first three cards were red, probably diamonds. Maybe hearts, but this was in the spring of 2011, years before anyone thought to make permanent note of such things. Definitely red, though, and definitely the same suit, and one was a queen, because Jack Alexander had a queen-high flush on the flop, which is the kind of hand a man remembers.

Jack was in Father Jim's Saloon, which was neither a fully equipped casino nor a permanent establishment but rather the function hall of St. James Catholic School in Torrance, California, tricked out for the evening with hay bales and such to give the place a country-western theme. Jack was playing poker for charity, the charity being St. James School itself. Raising money for the school was practically an obligation, like Communion or confession. On his tuition check, Jack had added $500 to the St. James School Education Foundation, a hundred dollars to the Big Red Raffle, a hundred to another raffle, and $225 so his three kids would be allowed to raise more money in a jog-a-thon. And that was just at the beginning of the school year.

Most parents didn't mind, though. Charity begins at home and all. The school was always short on funds, so families pitched in where they could. Cash, sure, but volunteering, too. Jack, for instance, coached a few of the sports teams and he'd co-chaired the golf tournament since 2005, brought in about ten grand the year before. They could do better, though, so Father Jim's Saloon got tacked on in the evening hours after the tournament: A fair number of golfers were poker players, so why not hit them up twice in one day?

The game was Texas Hold 'Em. One of the parents worked at a party-supply outfit, and she hooked up Father Jim's with four proper tables and dealers. The last time St. James had a Vegas night, two years earlier, Jack made it to the final table before he busted out. The principal of St. James eventually won, which wasn't all that remarkable.

Sister Mary Margaret Kreuper seemed to win a lot of stuff. Raffles. The Radio Flyer stuffed with booze at the Harvest Festival. But of course she did. She was a nun who'd devoted her life to Christ, the church, and educating children. “Misfortune pursues sinners,” Proverbs tells the faithful, “but the just shall be recompensed with good.”

Who's more just than a nun?

Sister Mary Margaret was at the final table again. In fact, it was just her and Jack left, probably more than $1,000 of charity chips at stake, and Jack pulled his queen-high flush on the flop.

Jack did not bet aggressively. He slow-rolled the sister, tried not to spook her into folding. She called.

The dealer turned over an ace. At best, Sister Mary Margaret had three of a kind, and that was assuming she had a pair in the hole. Another bet, more aggressive, Jack thinking, I'm gonna flush her out.

Last card. Another queen. Maybe she had two pair, queens and whatever she might be holding. Or she had a third queen. Neither one beats a flush.

“I'm all in,” Jack said.

As Jack remembers it, the sister didn't even blink. She smiled. “Me, too.”

Jack showed his diamonds, started to reach for the chips.

Sister Mary Margaret turned over an ace and a queen. Full house, queens over aces.

Jack stared, slack-jawed, at her cards. Man, he thought, this lady is one hell of a poker player.

1081012256

Jack Alexander wasn't terribly surprised he got cleaned out by a nun, or at least by that particular nun. A few of the parents, maybe a lot of them, had long suspected Sister Mary Margaret was a gambler, and probably a competent one.

There were little hints, asides and inflections, that other gamblers are tuned to. Like in 2008, when David Tyree pinned that third-down pass to his helmet in Super Bowl XLII and kept the Giants' last-chance drive against the unbeatable Patriots alive. “Did you see that catch?” Sister Mary Margaret asked Jack the day after. Except she said it the way Jack felt—like someone who'd put a few bucks on a sure thing, only to see New England lose on a fluke.

“A nun tells you they need money, you're gonna believe her,” Jack Alexander says. “Who thinks a nun is going to steal?”

Mostly, though, there was all the talk about trips to Las Vegas and Lake Tahoe. Sister Mary Margaret supposedly traveled to both with some frequency, usually with her housemate, Sister Lana Chang, who was also the eighth-grade teacher at St. James. If true, perhaps Sister Mary Margaret was simply visiting old friends, considering she used to teach at a school in Las Vegas. But that was more than 20 years ago. And why would Sister Lana go with her? Occam's razor doesn't slice that finely.

Editor-in-Chief Will Welch on GQ's first-ever Summer Beach Reads issue.

Still, no one much cared. The rumor was that Sister Lana had a rich uncle who paid for everything, so who's to judge what a sister does on her own time and an uncle's dime? If gambling was good enough for a fund-raiser, it was good enough for leisure time. The sisters took vows of poverty and chastity and obedience—why begrudge them a little poker on the side?

So no one did. Until this past November, when the families of St. James students received a letter from Monsignor Michael Meyers, the pastor of St. James Church, which oversees the school. “It is with much sadness,” he wrote, “that I am informing families of St. James School that an internal investigation has revealed that, over a period of years, Sister Mary Margaret Kreuper and Sister Lana Chang have been involved in the personal use of a substantial amount of School funds.”

Distilled into the plain English generally applied to laypeople, as opposed to nuns: The sisters stole a lot of money for a long time. Allegedly.

This had been discovered, he wrote, during a fiscal review initiated because Sister Mary Margaret, who was 77, was retiring, as was Sister Lana, who was 67. How much went missing? The monsignor didn't know, but the sisters' order, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, was “cooperating with us and the Archdiocese to confirm the amount of the funds that were misappropriated.” The Torrance police, Meyers wrote, had been notified, but neither the church, the school, nor the archdiocese would be pressing charges; instead, they would “address the situation internally through investigation, restitution, and sanctions on the Sisters.”

In his letter, Monsignor Meyers did not say for what purpose the money allegedly had been misappropriated. But five days later, at a meeting with families and alumni, a lawyer for the archdiocese offered a general sketch. Some of the money was recycled back into the school, Marge Graf, the general counsel for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, said. Though how much she did not say. More to the point, Graf said: “We do know they had a pattern of going on trips. We do know they had a pattern of going to casinos. And the reality is, they used the account as their personal account.”

A church accountant ballparked a number: $500,000.

That was very much begrudged.

Sister Mary Margaret Kreuper was 47 years old and had been a Catholic educator for more than 19 years when she came to St. James School in 1988. She'd taught fifth grade at Our Lady of Las Vegas and fourth at St. Patrick's in Pasco, Washington, and, in between, she'd been the principal at St. Stanislaus in Lewiston, Idaho. In a way, St. James was a sort of homecoming: She got her bachelor's in sociology from Mount St. Mary's College in Los Angeles, and she did her student teaching at two parish schools in the city.

St. James is a small school, though not unusually so for a Catholic one. It has a tidy campus of low buildings on a wide square of blacktop fronting Anza Avenue in Torrance, with 300 students, give or take, in kindergarten through eighth grade. There is a single teacher for each of the primary and middle-school grades, and students also have classes in art, Spanish, music, and physical education. The students and staff are not required to be Catholic, but most are because St. James is first and foremost a Catholic institution. It's right there on the home page of the website: “Preparing Confident, Competent and Caring Catholic Citizens.”

“Religious development,” in fact, is the first of five educational goals enumerated in the staff and faculty handbook. “We strive to influence the moral values of the child,” it says on page 6, “and hope to help each child strengthen his/her personal relationship with God.” The staff is expected to accomplish that by, among other things, “[e]xemplifying faith, charity, justice, honesty, courtesy and friendship,” and “[t]eaching the Gospel message and Catholic doctrine in such a way as to make them relevant to every day life.”

For the 30 years Sister Mary Margaret was in charge, all that molding and exemplifying was apparently done with an abundance of discipline and an inadequate amount of cash. She ran an orderly school: Idle classroom chatter was tantamount to chaos, and a desk with more than one pen, one pencil, and one eraser on it was unacceptably cluttered. Minor infractions—talking out of turn, inadvertently booting a kickball over the fence—were punished by walking the line, trudging in silence around a square painted on the asphalt. “As a parent,” Jack Alexander says, “you think they're teaching discipline.”

Meanwhile, the school ostensibly operated on a shoestring. There never seemed to be enough money for anything beyond the basics, and even those were apparently subsidized with that endless cycle of fund-raisers. The students ate their lunch on benches outside, and for years parents had asked for an awning to shade their kids from the Southern California sun. The answer was always the same: There's no money. Indeed, one of the last letters Sister Mary Margaret sent home to parents, in March of 2018, was to tell them the school had to raise tuition, apparently to cover the paychecks of her and Sister Lana's replacements. “You may already know that I do not receive a salary for my service as principal of St. James School,” she wrote. “As a member of a religious community, I receive a stipend for my work. The same is true for Sister Lana. The budget will be impacted by the added salaries next year.”

Technically, Sister Mary Margaret reported to the pastor of St. James Church, who since 2011 has been Monsignor Meyers. “He has the title of administrator, so he is my boss,” she once said. But his actual role at the school? “Absolutely none,” she said, “except to review the budget.”

The two sisters have said nothing publicly… Church officials won't say where either nun is even physically located; for all practical purposes, they've vanished.

As a practical matter, Sister Mary Margaret said, St. James School was hers to run as she saw fit. She developed the budget and organized the finances. She reviewed the lesson plans and evaluated the staff. She hired the teachers and renewed their annual contracts and, in rare cases, did not renew them.

One of the teachers she hired, in 1996, was Sister Lana. A decade younger than Sister Mary Margaret, Sister Lana has a master's in education from Loyola Marymount University, and at the time she came to St. James, she had almost 25 years of teaching experience. Three of those years were at St. Stanislaus in Lewiston, Idaho, during the period when Sister Mary Margaret was the principal. In Torrance, they shared a town house owned by the archdiocese for almost 20 years, and just before they retired—a week before Sister Margaret sent out the tuition letter—they agreed to put a $7,429.61 deposit on a three-bedroom, two-bath rental 15 minutes from the school.

“When I first heard about it,” one woman at the parish tells me, “you could have knocked me over with a feather. But then I thought about it and…well, I guess it's not that surprising.”

Memory is funny like that, the way it can sharpen and refocus. Shift the present and the past bends with it. Innocuous comments become obvious evidence, odd coincidence becomes cheap conspiracy. Did they, or their friends from outside the school community, really always seem to win at the raffles? Or is that a trick of memory?

Because nothing seemed sinister at the time—they were nuns, after all—the Vegas trips and Tahoe getaways were never mentally cataloged by anyone in the school community. So all that's left now is a determined sense that of course Sister Mary Margaret and Sister Lana gambled far beyond their means. It's one of those things everyone knows but no one knows.

Did they play the slots? Maybe. Blackjack, poker, craps? Possibly. Did they squeeze Vegas into weekends or wait for school breaks? Yes, unless they didn't. If no news, send rumors: Someone heard that someone said they had a house account at this casino or got comped at that casino. Thieving, gambling nuns is a wondrously dark and mostly blank canvas upon which any scenario can be sketched.

In his letter, Monsignor Meyers announced that “[o]ther staff persons were not implicated or responsible.” At the meeting, he seemed to suggest Sister Mary Margaret was so fiscally crafty that no one could reasonably have been expected to notice that the books of a small school were crooked, and apparently had been for years. The implication, then, would be that only the two sisters could possibly know what happened and when. Yet they have said nothing publicly. Sister Lana's personal attorney declined to comment, and Sister Mary Margaret's did not respond to calls or e-mails. Church officials won't say where either nun is even physically located; for all practical purposes, they've vanished. So their only statements—and purported statements at that—have been filtered through church officials (who also declined to comment further), and those have been wholly unspecific. “A pattern of going to casinos” leaves a lot of room for the imagination.

At the beginning of 2013, Sister Mary Margaret hired a woman named Kristen Biel as a long-term substitute for the first-grade teacher, who was on maternity leave. Biel used to be a dance teacher, but she did not have decades of experience in the classroom: She'd gotten her teaching credentials only a few years before, in order to help pay for her son's college tuition. She was good with kids, though, and was recommended to St. James by the principal of another Catholic school, where she'd been a substitute. “She seemed to be caring and nurturing,” Sister Mary Margaret said later, “and I believe you need to have that in first grade.”

Biel taught three days a week until the Easter break. Sister Mary Margaret watched her in the classroom every now and again—“walk-throughs,” she called them, sort of informal spot checks—and liked what she saw well enough that she offered Biel a full-time job teaching fifth grade the following year. Biel accepted.

Sister Mary Margaret did one written evaluation of Biel, in November 2013, not quite three months into the school year. Overall, it was favorable, but the principal had a few concerns. Clutter, mainly. “Observed many things on the desks, Kleenex box, markers,” she wrote. “Pencil sharpeners, water bottles, books, etc., under the desks and in the aisle. It's a fire hazard. Binders, staple removers, tape, Scotch tape.” She made a note that the kid could pack those things in zipper bags.

There were other issues, too, according to Sister Mary Margaret. Biel's classroom was “chaotic,” she would later say, which is a word she defines as “lots of talking, lots of getting out of their seats with seemingly no purpose, just because they wanted to go visit a friend.” Also, too many kids made the honor roll and none of them showed up in the homework room, which is where students have to go when they don't get their assignments done on time.

“I experienced her as being a very creative teacher,” Sister Mary Margaret said later, “and I think that the clutter and the ease with which she apparently graded these children was something that she thought was okay. It didn't bother her.”

Biel and the principal met periodically to discuss those points, and in February 2014, Sister Mary Margaret gave her a form asking if she intended to return the following year. Biel said she did.

Two months later, over the Easter break, Biel found a lump in her breast. She would need time for treatment—double mastectomy, chemo, radiation—but planned to return partway through the following year. Her last day teaching in 2014 would be May 23.

“We had to take our daughter to a counselor to try to explain how people… who've been holding them accountable their whole lives have done nothing but lie to them.”

Her students and their parents sent her cards and letters that spring. Lauren, Ava, Janeli, Elizabeth, Isabel, and Emma told her she was the best teacher they ever had, and Ryan G. said she was the best teacher in the world. Taylor wanted to be just like her—“kind, caring, strong and brave”—and Ellie's mom wrote, “I just wanted to thank you for all the wonderful things you have added to Ellie's fifth grade experience. You have challenged her and, at the same time, encouraged her creativity.” Ryan H. promised he'd “never forget the year that you were my teacher and how you made school fun.”

“You are my favorite teacher because you told me how to study,” Brandon wrote. “I really improved my grades. I am much more confident.” His parents sent a letter, too: “People have often said one teacher can make a difference in a child's life. Mrs. Biel, you are that teacher for Brandon.”

On May 15, a week before Biel was to leave and prepare for her cancer treatment, Sister Mary Margaret put a letter in Biel's staff mailbox. “Dear Kristen,” it began. “At this time I am not prepared to offer you a contract for the 2014–2015 school year at St. James School.”

In his letter to families announcing the alleged theft, Monsignor Meyers said that Sister Mary Margaret and Sister Lana are very sorry. The nuns “have expressed to me and asked that I convey to you, the deep remorse they each feel for their actions and ask for your forgiveness and prayers.”

At the meeting with families a few days later, another nun read a letter from the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet saying the same thing. “We want you to know from us, the sisters have taken responsibility for their actions, and are deeply remorseful for what has happened.” And, in a clumsy and sterile sentence seemingly stripped of remorse: “Sister Mary Margaret has asked us to convey that she does not support public communications suggesting she is not responsible.” It was unclear, however, who might be suggesting such a thing.

Also unclear is exactly what the sisters are sorry for. (And, again for the record, whether they should be sorry for anything: Church officials have said Sister Mary Margaret admitted to taking money, and that both sisters are remorseful, but no one's heard directly from them.) No one could say with certainty how much was taken and over what period of time. At this point, a reliable accounting might not even be possible.

The financial review was merely a trigger. It was a procedural audit, not meant to crunch the numbers but only to make sure there were proper mechanisms in place to do so. But at the same time, and apparently by happenstance, one of the St. James families needed a copy of an old tuition check. “When we got that check,” Monsignor Meyers said at the meeting, “it was noticed that the endorsement on the back was not for the St. James School account.… It was an account that nobody knew about.”

Meanwhile, Sister Mary Margaret was acting squirrelly, he told the families, asking for some files to be changed and such. “Some strange things began to happen as she got ready for the review,” he said. So a forensic auditor was called in to comb through the books.

That all happened in May and June of 2018. Six months later, the auditors still couldn't offer a final number. The $500,000 figure is what they've managed to sift from a single checking account going back to 2012, officials said at the meeting, prior to which detailed bank records weren't available. But that particular account was opened in 1997, and Sister Mary Margaret was there a decade before that. “Does it go back ten years?” Meyers asked at the meeting. “Or 15 years? Or 20 years or more?”

And was that the only account? Why would it be? One parent told friends she hunted through old checks and found at least five more account numbers she considered suspicious. And what about the cash, all those fives and tens and twenties swirling through casino nights and festivals and raffles, thousands upon thousands of dollars in small bills?

At the meeting, Marge Graf, the diocesan lawyer, conceded cash was “a significant other issue.” Yet she also seemed genuinely surprised to see so many angry parents show up. As several of those parents pointed out that night, a layperson who looted a half-million from a school would be in handcuffs, and probably perp-walked for the cameras, too. But two nuns allegedly do it, and no one even calls the police? St. James informed the Torrance Police Department, but not until six months after the fact, and initially declined to file a criminal complaint. (That changed 11 days after the meeting. Moreover, bank fraud is a federal crime, and the alleged misappropriation is possibly being investigated as such. In April, a spokesperson for the archdiocese referred me to a prosecutor in the Major Frauds Section in the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Central District of California. That office declined to comment. In any case, by May, no one had been charged with any crime.)

The matter was to be handled internally. Church auditors, and independent auditors hired by the church, would investigate, the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet would make restitution, and Sister Mary Margaret and Sister Lana would suffer “canonical sanctions,” a phrase uttered with tremendous ferocity but amounting to, according to Graf, really strict probation, albeit without the inconvenience of court supervision and a criminal record.

“I'm trying to be extremely transparent, candid, and open with you,” she said. “And yet I understand, and I hear, those of you who say, ‘That's not enough,’ or ‘That's not how I feel,’ or ‘That's not what I want played out.’ So understand, I hear you on those points.”

“They teach you: Thou shalt not steal,” Jack says now. “But then, you're supposed to forgive.” He sighs. “But wait a minute, they stole from my kids.”

But hearing is not the same as understanding. The meeting roiled for two hours, parents and alumni questioning, probing, venting. Their anger was fed not by vengeance but betrayal. “My daughter wanted me to speak tonight,” one woman said, “because we had to take her to a counselor to try to explain how people who made them walk the line…people who've been holding them accountable their whole lives, have done nothing but lie to them.”

And what of remorse? Does it count if you wait until you're caught? Does it matter if someone else reads it from a letter?

“How can you ask for forgiveness if you don't look someone in the eye?” another mother asked. “An apology from them coming through you does not mean very much to me.”

Monsignor Meyers considered that. “All we can do is see where the sisters are at, what they're willing to do,” he said. “But it also depends on what we're willing to do. If they come here to ask for your forgiveness and for your understanding, [and] if you're going to sit here and throw tomatoes at them, no, I don't think they ought to come.”

Kristen Biel sued St. James School in Federal District Court under the Americans with Disabilities Act, arguing that her contract was not renewed because she needed time off for cancer treatment. Sister Mary Margaret, she claims, told her “it was not fair…to have two teachers for the children during the school year.” In a 2015 deposition, Sister Mary Margaret denied that, maintaining she had decided in March 2014 to not rehire Biel because of her performance, including the ongoing clutter and chaos in her classroom. Her May 15 letter terminating Biel says as much, though it's important to note that was written after Sister Mary Margaret knew Biel had been diagnosed with cancer.

That's an issue of fact for a jury, and one that likely will hinge upon whom the jurors find more credible, the teacher with a stack of testimonials from students and parents, or the nun who allegedly fleeced her own school. But that's assuming Biel's case ever gets to trial.

St. James got it dismissed once, in January 2017, by invoking the so-called “ministerial exception.” Because the First Amendment gives religious institutions the right to hire their own clergy and other superiors—Baptists, for instance, can't be forced to keep atheist preachers on the payroll—federal employment law doesn't cover an employee who reasonably can be considered a minister. There is no precise legal definition of the term, but the Supreme Court, in a 2012 ruling, laid out four general guidelines to help judges figure out who is and isn't a minister.

Three of those guidelines seemingly didn't apply to Biel. The school did not consider her to be a minister, she never presented herself as one, and nothing in her title—fifth-grade teacher—suggested she was. The fourth, however, was whether her job involved “important religious functions.” The school argued that it did: For 30 minutes four days a week, Biel was required to teach her students about Catholicism. She went over the saints and the sacraments, the Gospels and Catholic social teachings, not from any specialized personal knowledge but from a textbook called Coming to God's Life. That was enough, the school maintained, to exempt Biel from suing under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

In other words, because Biel spent two hours a week instructing children in the ways of Catholicism—because she was helping to shape “Confident, Competent and Caring Catholic Citizens,” as the motto has it—Sister Mary Margaret was free to terminate her employment at will as she prepared for a double mastectomy.

A judge in Federal District Court agreed. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, in a 2–1 decision, did not: On December 17, exactly two weeks after Monsignor Meyers asked a crowd to forgive two sisters for stealing them blind, the case was remanded back to the trial court.

A month later, the school petitioned the full Ninth Circuit to reconsider. The court had not ruled by May.

There was this one Sunday morning, years ago but clear as yesterday. Jack Alexander was 5 years old, walking to church, St. Francis by the Sea, in Laguna Beach. He was with his cousin, three years older, that much bolder. His cousin slipped into a corner store, pinched a couple of pieces of Bazooka, gave one to Jack. He popped it in his mouth.

His aunt was waiting for them at church. She looked at both boys. Or was she staring? Jack wasn't sure.

She spoke. “Thou shalt not steal.”

Shit. Did she know? Jack's palms sweated, heart pounded. He wondered if he should swallow the gum, hide the evidence.

Wait. She's not mad. Did she even say that? Or was it a guilty echo from his lizard brain?

“I mean, c'mon,” Jack says now. “That's the first commandment they teach you: Thou shalt not steal.”

He sighs. “But then, you're supposed to forgive.”

Another sigh. “But wait a minute,” he says. “They stole from my kids.”

Curiously, not everyone sees it that way. In his initial letter to the families, Monsignor Meyers wrote that “notwithstanding this misappropriation”—or theft, of an unknown amount over an unknown period of years—“no student or program at St. James has suffered any loss of educational resources, opportunities, or innovations. In sum, the education of your children has not and will not be affected by these events.”

He said as much at the meeting, too. His flock is not that credulous. It's the equivalent of arguing that not having a million dollars does not affect one's ability to be a millionaire. Every dollar lost was a dollar that could have been spent replacing old textbooks, giving teachers raises, installing a simple awning so the kids don't get sunburned at lunch.

And dollars and cents aren't the point, anyway. “Our education was affected,” a girl who graduated from St. James in 2015 said at the meeting. “We sat there day after day in class being berated verbally on what to do, what to say, what to wear, and how to act by Sister Mary Margaret and Sister Lana, who were telling us we did everything wrong,” she said. “Yet they were over here committing federal crimes and stealing our parents' hard-earned money for their personal benefit.

“I was called a liar,” she said, “by a woman who's the biggest liar I've ever known.”

As if that weren't clear enough, a parent of another graduate clarified further. “Whether you want to believe it or not,” she told the assembled church officials, “this has now become part of their education.”

St. James School taught them their moral superiors are not, in fact, superior.

By springtime, few parents wanted to talk publicly anymore. Even the woman who put five boys through St. James and messaged other families with the suspicious account numbers she'd found on the backs of some of the old checks she'd collected—she'd said her piece, done her due diligence, and now would rather wait out the investigation.

Jack introduces himself as “the loud guy,” simply because he's the only one talking on the record. He gets it. It's embarrassing, getting swindled for…well, hell, he doesn't know how much. No one does. “A nun tells you they need money, you're gonna believe her,” he says. “Who thinks a nun is going to steal?”

And that's part of it, too. This all happened in the context of a church, of a community of people who worship together, who put their collective faith in the Holy Spirit and one another, who in simply coming together are conceding we all fall short of the glory of God, we're all imperfect, we're all sinners. That house does not stand divided.

Jack doesn't go anymore. “It got awkward,” he says.

Someone needs to be the loud guy.

Still, he does not want vengeance. He can't imagine anyone is going to send two elderly nuns to prison, no matter how much they might have stolen.

But he wants them in court. He wants Sister Mary Margaret and Sister Lana, the women to whom he entrusted the academic and moral education of his three children, to stand up in front of a judge, and then turn and look at all the students gathered in the gallery.

“And I want them to say they're sorry,” he says. “I want them to say they're frickin' sorry for being full of shit. That's what I want. That's what the kids deserve.”

Sean Flynn is a GQ correspondent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the June/July 2019 issue with the title "Holy-Rollers."

Originally Appeared on GQ