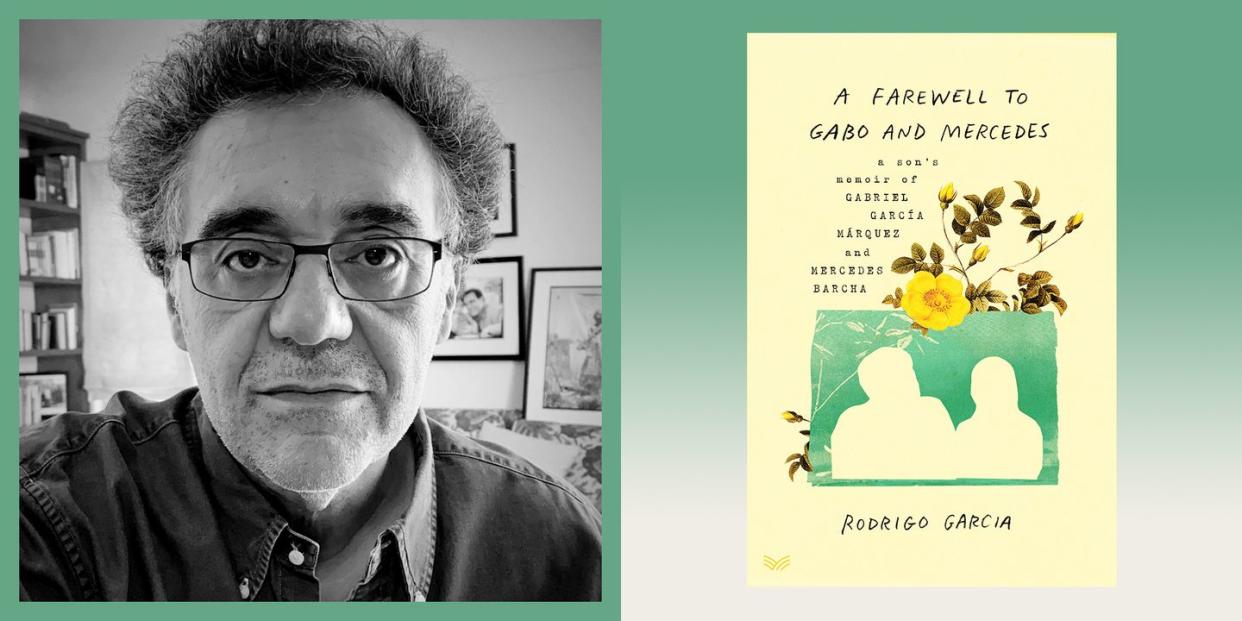

Gabriel García Márquez's Son Wrote a Beautiful Memoir About His Parents

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Literary titans have an aura of immortality about them, so it comes as a shock when even they are subject to illness or old age—when it turns out they are human after all. Rodrigo Garcia captures those feelings in his spare, affecting memoir, A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes, which conjures his father, Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez, and his formidable mother, Mercedes Barcha, known to her sons and grandchildren as El Cocodrilo Sagrado (“The Sacred Crocodile”) and La Jefa Máxima (“The Boss Supreme”). By keeping a tight focus on his father’s difficult death, played out in weeks, the author expands our sense of marriage, warts and all, as well as the complicated parent-child relationship and the layered calling of the artist.

Born in his parents’ native Colombia, Rodrigo grew up in Mexico City, where his parents settled. After graduating from Harvard, he built a stellar career as a film and television producer and director, working on such acclaimed series as Six Feet Under, The Sopranos, and Big Love, which netted him an Emmy nomination. In his memoir, he considers his life choices and how he deliberately steered away from the shadow of his father’s achievements.

And then he got a call in early 2014. At the age of 87, García Márquez—a colossus of 20th century literature, author of One Hundred Years of Solitude, Love in the Time of Cholera, and other canonical novels—was ebbing away, his body wracked by cancer, his mind gutted by dementia. His wife of 57 years, summoned her sons: Rodrigo from Los Angeles and Gonzalo from Spain.

Rodrigo recounts his father’s final weeks, his mother’s resolve, and his own welter of emotions. He checked in with his father’s caretakers. He consulted Gabo’s team of physicians, who kept cutting back García Márquez’s life expectancy from months to weeks to days. He jotted notes. And most poignantly, he scrutinized his mother as she journeyed through Gabo’s end-stage in a haze of insouciance and cigarette smoke. Mercedes leaps off the page as “a living, breathing, textbook example of avoidance . . . in its own way, beautiful.”

He then breaches the walls that surround his father’s genius, bringing us into the circle of the three people who knew García Márquez best. His tone is intimate, confidential, tender. There’s a dreamlike quality, too, as he weaves in Polaroid-like glimpses of his father; here, Gabo is down-to-earth, dismissive of critics and publishing cliques, adamant that nothing interesting had ever happened to him after the age of eight. The quirks of a creative family emerge. When a bird is found dead inside the house, the staff are divided on whether it’s a good or bad omen; they eventually bury the carcass in a plot of garden known as the pet cemetery, where a parrot and a puppy rest in peace. His father, Rodrigo observes, would have been “perturbed” to know of the cemetery’s existence.

Death is a hallmark of A Farewell to Gabo and Mercedes, but a gentle ironic humor also suffuses the book. After a drawn-out decline, Gabo slips away as family and friends gather for a cocktail party. Outside the estate, journalists and paparazzi cluster, desperate for a photo or headline. When Rodrigo escorts his mother to view her husband—a man she’s known since childhood—she smooths a sheet around Gabo and caresses his forehead. “She erupts in tears,” Rodrigo writes. “I’ve seen her cry only three times before in my whole life. This one lasts only a few seconds, but it has the power of a burst of machine-gun fire.” The son has clearly inherited some of his father’s literary DNA.

Diva mask back in place, Mercedes greets visitors and Gabo’s mourners cordially if coolly, denouncing a few behind their backs. Six years later, she faces her own mortality, a casualty of lung cancer, but brimming with acerbic gossip until the end, fully herself. In a valedictory paragraph, Rodrigo evokes how our parents linger, ghostly:

“The death of the second parent is like looking through a telescope one night and no longer finding a planet that’s always been there,” Rodrigo writes. “It has vanished, with its religion, its customs, its own peculiar habits, big and small. The echo remains. I think of my father every morning when I dry my back with a towel the way he taught me after seeing me struggling with it at the age of six . . . I remember my mother each time I walk a guest to the front door when they’re leaving, because not to do so would be inexcusable, and whenever I pour olive oil on anything. And in recent years, the three of us look back at me from my face in the mirror.”

You Might Also Like