The Future Of Men's Fashion Is Female

Welcome to GQ's New Masculinity issue, an exploration of the ways that traditional notions of masculinity are being challenged, overturned, and evolved. Read more about the issue from GQ editor-in-chief Will Welch here and hear Pharrell's take on the matter here.

Imagine you're a movie star. Your life is one long red carpet, lived in the same suit night after night, with just a few tweaks (midnight blue on Wednesday, Prince of Wales checks on Thursday). And at the end of it all: a tuxedo!

But maybe you're feeling bolder. Maybe you feel your clothing should say something truer about you. Men aren't just pieces of roasted asparagus tailored into inky worsted wool. Men are creative. They are sensual. The sands of masculinity are shifting—shouldn't the way men look say as much?

So you wear a frock coat instead of a peak-lapel tuxedo jacket in snooze black. You wear an oil-blue suit covered in islands of sequins, or a gingham dinner jacket like you're an English professor who's pivoted to a new life at the Grand Ole Opry. Maybe a ruffled micro-dot blouse under a black tuxedo—the tailoring not too skinny, the look sensuous as a pinprick.

Or maybe you're not famous. Maybe you're merely fabulously rich. (Isn't this fun?) Everything else in your life is just the way you want it, just the way you dreamed it—why not your clothes as well? After all, your clothing needs to say something grander than just “expensive.” What if someone could put your passion into a garment and you could wear it? Your heart on your actual sleeve—now we're talking! What if a jacket covered entirely in sequins hung on you light as the burden of being born rich and your pants fit so perfectly that your self-esteem improved?

Congratulations: This is life wearing Givenchy.

The woman behind this fantasy is the English designer Clare Waight Keller, who has been Givenchy's artistic director since 2017, overseeing both menswear and womenswear for the venerable French fashion house. It was her vision for a new, more holistic version of the brand that helped her land the job. “My initial process going in, and actually even in the talks of looking to join Givenchy, was about the fact that I very much saw the house as a very strong vision of a couple,” Waight Keller told me when we first met, in Florence, Italy, this past June. She explained that she drew inspiration from the relationship between the house's namesake and founder, Hubert de Givenchy, and the actress Audrey Hepburn, who began working together early in the 1950s. “You kind of always saw them as this fashion couple,” Waight Keller said.

She had arrived in Florence just 90 minutes before we sat down to chat, having come to present a menswear collection as the special guest designer at Pitti Uomo, the Italian trade-show leg of the Men's Fashion Week circuit. The show was about 48 hours away. We were seated in a sort of meeting room on the ground floor of the boutique hotel where she was staying—a place that had been designed to feel like a private home. There was no lobby, really, which meant that Italian “zaddies” with miraculously groomed chest hair wandered in and out as we spoke, glancing curiously at the fresh-faced British woman at the head of a dining room table covered in an orderly array of documents.

Suddenly, there were “all these a-list actors and musicians,” Waight Keller says, who wanted to “really wear this idea of a more flamboyant man.”

She was, she told me, essentially finished with the clothes she'd be showing: “Last weekend, basically in three days, I put the collection together in terms of the styling, and the mood, and the attitude. And tomorrow, really, I've got some final fittings.” Still, Waight Keller's work never seems to be completely done. During the two months that I followed her, she presented three collections composed of 157 total looks. I asked her at one point, late in the summer, whether she ever got tired. She laughed and said, “Yeah, sometimes!” quickly adding, “I get a lot of energy from my work. I really love it. I do.” And then she extolled to me the virtues of the European holiday. The secret to her success, she seemed to suggest, is that she knows how to relax. So chic.

In person Waight Keller seems like an American's fantasy of a British person: incredibly warm, with a look best described as “lovely”; her hair is just a bit blonde and wavy, and her cheeks always have a peachy glow. Often she looks as if she's spent the past three days in the country, riding a horse named Passport or something. But in fact she typically spends half the week in London—where her husband, architect Philip Keller, and their three children live—and the other half in Paris. She's a low-key dresser, favoring things like army green capri pants, linen shirts, and simple leather sandals—a bit like Gwyneth Paltrow, with a Malibu-by-way-of-London stylishness. Her sense of humor is just a little naughty. She'll describe her work with words like “anarchist” and “sleazy” and “perverse posh.”

When she first arrived at Givenchy, almost three years ago, the priority that she set for herself, she told me, was to reanimate the elegance of the iconic French couture house. For the previous 12 years, under Riccardo Tisci, Givenchy had been defined as a baroquely brash fusion of streetwear and aggressive tailoring. Waight Keller was interested in something more feminine. For actresses like Rachel Weisz, Rosamund Pike, and Cate Blanchett, Givenchy became the go-to brand for slightly freaky red-carpet looks. And last year, when she designed the dress that Meghan Markle wore to wed Prince Harry, Waight Keller sealed her reputation as a defining voice of feminine glamour, a propagator of fashion as fantasy—of dreams that felt accessible, modern.

But all the while, she felt there was room to grow in menswear. Unlike with other big fashion houses, where womenswear is the more lucrative machine, Givenchy's business is “50–50” she told me. And since her spring 2018 couture debut, which provocatively included men's clothes, a buzz had been building. Suddenly, she said, there were “all these A-list actors and musicians immediately wanting to come to the house and order and really wear this idea of a more flamboyant man, but with a strong structure to it, a strong sense of tailoring.”

Waight Keller's menswear doesn't look girlish—rather, it looks louche, luxurious, and even flirtatious.

She knew she could push the vision further—that as a menswear designer, she had more things to say. So in January she held a confident but understated presentation—fluid, glam tailoring and sportswear, with a sense of unplaceable retro—during Paris Men's Fashion Week. The excitement she was generating amplified in the spring, when Givenchy announced its massive show at the menswear-only mecca Pitti Uomo.

Though the show was now only two days away, Waight Keller seemed anarchically calm. Given the duties she juggles, Waight Keller might be the hardest-working designer in fashion. But you wouldn't know it, either from her presence on Instagram, a place where fashion-industry people love to share footage of themselves flinging around the world in pursuit of the next exotic #inspo, or from her demeanor. She radiates calm and approachability—a striking contrast to the French couturier archetype (usually: angry, and a man). I asked her how she balances all these collections, many of which require simultaneous work and separate visions, and she said simply, “I'm organized!”

One would have to be to handle just her growing responsibilities in menswear, a fashion category that suddenly finds itself at the center of the industry's attention. Within LVMH, the conglomerate that owns Givenchy, menswear has become a major focus: Louis Vuitton, Dior, and Berluti all appointed new menswear designers in 2018. The star power in particular of Dior's Kim Jones and Vuitton's Virgil Abloh—not to mention that of their supporters and friends, including A-list models and musicians—has brought a new level of excitement to men's clothing and the attendant fashion weeks, especially in Paris.

“This is why I'm moving towards men's shows, because I think it now really warrants it,” Waight Keller told me, excited about the possibilities for menswear to become as much an obsession—even a lifestyle—every bit as grand and glamorous as womenswear. “I want to start moving the menswear up to that level,” she said. I ask her about the show in a couple of days and about the message she wants it to convey. “It's the independent vision of menswear,” she said simply, like it's no big deal.

Waight Keller has a way of making the remarkable seem understated—sensible, even. This includes her own arrival at Givenchy, in 2017, which was greeted as a major moment in fashion's recent feminist wave. For over a century, the great irony of the Paris ateliers was that while they were the world's premier manufacturers of female fashion fantasies, they were mostly led by men.

With the exception of Elsa Schiaparelli and Coco Chanel, all the great couturiers of the so-called golden age—a period that stretched from just after World War II through the late 1950s—were men. Hubert de Givenchy, Cristóbal Balenciaga, Christian Dior, and Pierre Balmain. As time marched on, those eponymous couturiers were replaced with more men.

That narrative began to change when, in 2016, Maria Grazia Chiuri was appointed artistic director of Dior, overseeing womenswear, and when, a year later, LVMH announced Waight Keller as the new artistic director of Givenchy.

She stepped into the role after spending six years at Chloé, a brand that is the flirtatious embodiment of the French woman—all flounce and bohemia. There the silhouettes she perfected derived from a draping technique called flou, of which Waight Keller is a modern master. Despite her feminine bona fides, her résumé had, up to that point, swung between menswear and womenswear: She designed womenswear for Calvin Klein, served as the head men's designer for Ralph Lauren's Purple Label, oversaw womenswear at Gucci under Tom Ford, and spent the early years of the 21st century making men's and women's clothes at Pringle of Scotland, a once modest knitwear company that she helped grow into a global luxury brand.

At Givenchy, Waight Keller was following in the high-profile footsteps of some of fashion's more provocative personalities: John Galliano, Alexander McQueen, and Tisci. You know, bad-boy designers. When Tisci (now Burberry's chief creative officer) joined the house in 2005, he mingled fashion with hip-hop at an unprecedented level. He filled his runway with sweatshirts and tees and was one of the initial high-fashion designers to take sneakers seriously, turning out $900-plus high-tops. Tisci was a true predecessor for Abloh, with his big persona and his posse, the “Givenchy gang,” whose ranks included Kanye West, Joan Smalls, Kendall Jenner, Madonna, and even Marina Abramovi´c.

If Tisci succeeded in convincing people that streetwear ought to be thought of as luxury, Waight Keller has an even grander goal in mind: She wants to elevate the art of men's clothing to its full potential, Fashion with a capital F. Even as menswear booms, it doesn't yet quite cast the spell that womenswear can over its customers, who become willingly mired in a vision crafted from an airy Parisian salon.

Of course the ambitious Florence show, which was being staged at a sprawling estate just outside town, would go a long way toward helping her make her case. The plan she'd worked up for the show at the sumptuous Villa Palmieri would feature what Givenchy had described as its “longest runway ever” (about 1,600 feet), down which Waight Keller would send nearly 60 looks. As for those clothes, Waight Keller told me something straight out of the playbook from the golden age of couture: “The mission I've made for myself is that you don't desire it until you see it.”

Unlike other hobbies, clothing—and fashion specifically—doesn't demand that you define yourself. The fantasy aspect of fashion celebrates who you could be.

The next day, as advertised, Waight Keller had some final fittings, which I was permitted to attend. In the living room of the Villa Palmieri, I found her perched on a couch, dressed in a black sleeveless dress with a silk drop-waisted skirt. She again appeared almost unbelievably at ease, greeting every model by name.

Her young team looked cool, and their collective mood was buoyant. They seemed more like they were preparing for a fun creative project than a giant global event, industriously tweaking things with a pleasant precision.

A model entered in a suit—the pearl buttons gleaming, the pants pooling in a supercool way, the color just a puff of blue. (As a testament to fashion's current approach to gender, the model was a woman, Sora Choi, who had a pouty, boyish charm. “You are coming to a men's show, if you're wondering,” Waight Keller joked to me.)

Over the suit was an icy white floor-length hooded raincoat that discreetly snapped onto the suit jacket under the lapel. As Choi walked up and down a short strip of makeshift runway, the coat caught the air in a fantastic, elegant parachute, glossing the model's clipped pace with an aristocratic ease, the way a country gentleman's coat glides while his horse gallops. It had all the dramatic flow and movement of a gown.

Studying the model, Waight Keller asked, from about 10 feet away, if the snaps connecting the raincoat to the suit at the lapel could be moved one centimeter forward. “Just a small refinement [on] something will make it that much more precise, or that much more cohesive,” she told me later. “And I think menswear particularly has that rigor in it, anyway.”

Designers who move between menswear and womenswear tend to borrow the hallmarks of the former to bequeath them to the latter. In other words, they take the tailoring and the sense of “timelessness” that flourish in menswear and apply them to the “trendiness” that abounds in women's ready-to-wear design. Waight Keller moves in the opposite direction. She began by taking that flou she had perfected at Chloé—that sensuality, that drape that makes fabric fly—and used it as the basis for her suiting (like the magic trick she performed with that white raincoat).

This sort of work requires deep expertise in pairing textiles, matching light fabrics with technical materials. What she does, she explained, is bring her knowledge of “the fluidity of the fabric and how it moves but translate it to menswear.” In this way, the go-to adjectives of French womenswear—ethereal, romantic, floaty—are in the menswear vocabulary now too.

Menswear is typically the story of minute changes made at a glacial pace—think how little the suit has changed in the past 100 years—whereas womenswear urges forward with an unquenchable thirst for novelty. In a womenswear collection, you might have 10 silhouettes, but in men’s you’ll see more like three. Waight Keller wants to infuse menswear with the pace and energy that’s endemic to women’s. “I’m constantly pushing, nonstop, to evolve the silhouette quickly,” she said. In making womenswear, she labors over the perfect pants for the perfect jacket and the right proportion for a trouser to wear with a specific shirt. “And that is something I wanted to echo in menswear,” she said, that “I didn’t think that was there.”

The identity play intrinsic to womenswear has always been the source of its power—wear big shoulders, for example, and look boardroom-ready, even if you don’t feel it. Waight Keller isn’t the first to inject femininity into menswear in the current era; Alessandro Michele found immediate success with his initial Gucci collection, in 2015, by sending out pussy-bow blouses whose short sleeves made them look borrowed-from-the-grandmas, the Persian lamb coats rich girls wear while taking smoking breaks at art school, and those pervy-luxe fur-lined slides. (Incidentally, Michele and Waight Keller were colleagues at Gucci, where she oversaw womenswear.) But Waight Keller’s men’s clothing doesn’t look girlish or womanly—and “it’s not to do something feminine,” she told me of her womenswear-driven approach to menswear. Instead her clothes look louche, luxurious, and even flirtatious. Unlike other hobbies, clothing—and fashion, more specifically—doesn’t demand that you define yourself. The fantasy aspect of fashion, that foundation Waight Keller is now building on, celebrates who you could be.

In a pixelated floral frock coat, you’re a European prince who’s exiled and loving it. In your oil-slick blue shell coat, worn over your blue suit and your teal turtleneck, you’re the kind of guy who can work a turtleneck. Remove the shirting from beneath your glowing lavender suit and suddenly you’re not behind your desk but behind the bar at the Hôtel du Cap-Eden-Roc. Leave the jacket unbuttoned and you’re buying rounds. Just put on a jacket, her clothing suggests, and play.

For the show the next night, Givenchy lit the Villa Palmieri with a fashion photographer’s romantic sensibility. Trees had never looked better. The estate was almost embarrassingly resplendent in that classic Italian-countryside way: The place seemed to be in a perpetual sigh of lazy opulence.

To the property’s natural beauty, Givenchy had added Instagram-ready flourishes: a comically huge chess set, a limousine-length Foosball table, and an endless supply of Champagne. By 9 p.m., some 500 guests—including notable celebrities who wouldn’t otherwise attend Pitti and who’d flown in just for the night—were seated alongside the long runway that looped through the gardens and terrace. And then the models began clomping down the runway in Waight Keller’s romantic mix of tailored sportswear and suiting. Their hair, mussed in a kind of Brit-pop chop, accented the clothes—which were the colors of butter, electrified cornflower blue, and baby-pig pink—with a requisite bit of Waight Keller naughtiness.

After the show, the scene melted into a party, where music blared and people spilled out onto the balcony and wandered around the gardens. Nothing gets the people going like someone else’s property to behave badly in! Waight Keller circulated in black trousers and a simple men’s button-up, the sleeves rolled to her elbows. On her feet were a pair of the sneakers she’d debuted that evening. She posed with Victor Cruz, Darren Criss, and Mena Massoud and hung out with her staff, laid-back and laughing.

It can be hard to square Waight Keller’s unassuming attitude with the apparatus of corporatized glamour propagated by the fashion industry. She has no arrogance, no ego; she really is as organized as she said—nothing catches her off guard. Even when she should be exhausted, she’s ready with quick and gratifying answers. Her exacting, productive manner inculcates a feeling that everything around her is effortlessly correct. It is perhaps a particularly feminine way of moving through the world; she makes you feel like your snaps will always be moved one centimeter in the right direction. Actors often tell her that when they wear Givenchy, they “just feel amazing in your clothes.” They say: “I know that you know how I feel in these clothes.”

As Waight Keller herself will tell you, it’s in couture that she performs her most innovative work. Couture is the great locus of fantasy in fashion: Every piece is made to order. These are garments created for occasions that you can only dream of, worn by people you can only really imagine. And it’s her couture designs that have won Waight Keller the most industry praise. As critic Tim Blanks recently wrote, hers are “clothes for alt-Hollywood.”

“I felt that was missing: that approach of doing really extraordinary, fabulous clothes for men to dress up in too,” Waight Keller said. “The couture customer is really looking for that extraordinary piece.”

1131933766

It was a few weeks after the Florence event, and we were having tea in a Paris hotel, just 12 hours after she’d presented her fall 2019 couture show. Bespoke clothing has been a part of menswear since luxury tailoring took hold on Savile Row. But haute couture is not your grandfather’s made-to-measure tweed. After tea I went to the atelier to see the fall 2019 couture pieces, like a silver sequined frock coat, up close. Waight Keller had imagined a group of aristocratic ne’er-do-wells invading a château, and this coat was meant to reflect the maddeningly fine silverware in the house’s collection. (Waight Keller seems particularly energized by the idea of breaking into rich people’s homes.)

But even without the fantasy origin myth, a coat like this is a technical triumph. Heavy embroidery will always make fabric collapse, so first the artisans in the atelier had to find exactly the right fabric to support the embroidery and hold the sharp, round shape for which Waight Keller’s men’s couture is known. The specialists in the atelier—some gifted in the application of sequins, others in the arrangement of beads—covered the coat in a mirror-like parquetry of overlapping square sequins, considered more modern, more masculine, than traditional round ones.

And on top of that, Waight Keller wanted to integrate the motif running through the rest of the collection: Braquenié’s celebrated “Tree of Life” pattern, a favorite of Hubert de Givenchy’s. The entire coat was embroidered with this design, in breathtakingly ornate combinations of pale silver pewter and deep gray tendrils of bullion chain and even thinner silver threads, all choreographed to create leaves, fruits, branches, insects, and blossoms climbing up and outward in a seductive sprawl.

The whole thing weighs about as much as a shrug and is lined with silk, so it’s unexpectedly breezy on the body. Light bounces off the sequins and onto the wearer’s face. The model in the show, with that Brit-pop crop and snobby moue, looked like a nightclubbing Narcissus, disco-dappled with his own reflection.

When it comes to couture, the haters always ask: Who actually wears this stuff? Well! For one, Jordan Roth—the president of Jujamcyn Theaters, the company behind hits like Kinky Boots and The Book of Mormon—has been a Givenchy Couture customer since Waight Keller started. (He’s a self-described “couture devotee,” having also worked with Iris van Herpen and Maison Margiela Artisanal.) “For me, what I wear is a kind of performance in the most rigorous sense of the word, the most meaningful sense of the word,” Roth said. “It is a bringing to life, bringing out what is inside. The process of conceiving that—manifesting those ideas into a design, crafting it and then wearing it—is the performance of couture.”

These kinds of performances often occur in private; a house’s clientele is highly secretive, along with almost every other element of the business. Roth is one of the rare well-known-but-noncelebrity couture clients, and when I asked if he could give me a sense, in whatever way he felt most comfortable, of how much these garments cost, he demurred: “I don’t think I can.”

And then there’s the red carpet. Over the past decade, the red carpet has increasingly become the spot where the conceptual fantasies of Paris have the attention of the entire world. Female actors from Lupita Nyong’o to Kristen Stewart have demonstrated how a more personalized public wardrobe can raise a celebrity’s profile and give those who see it a more meaningful sense of the artist within. As a result, it’s a place where standards of beauty and taste are challenged, reconsidered, and broadened. Menswear, though, has largely remained static on the red carpet. Being “daring” has long meant…wearing midnight blue. Abloh, Jones, and others are shaking the foundations slightly. But it’s Waight Keller who’s leading the revolution.

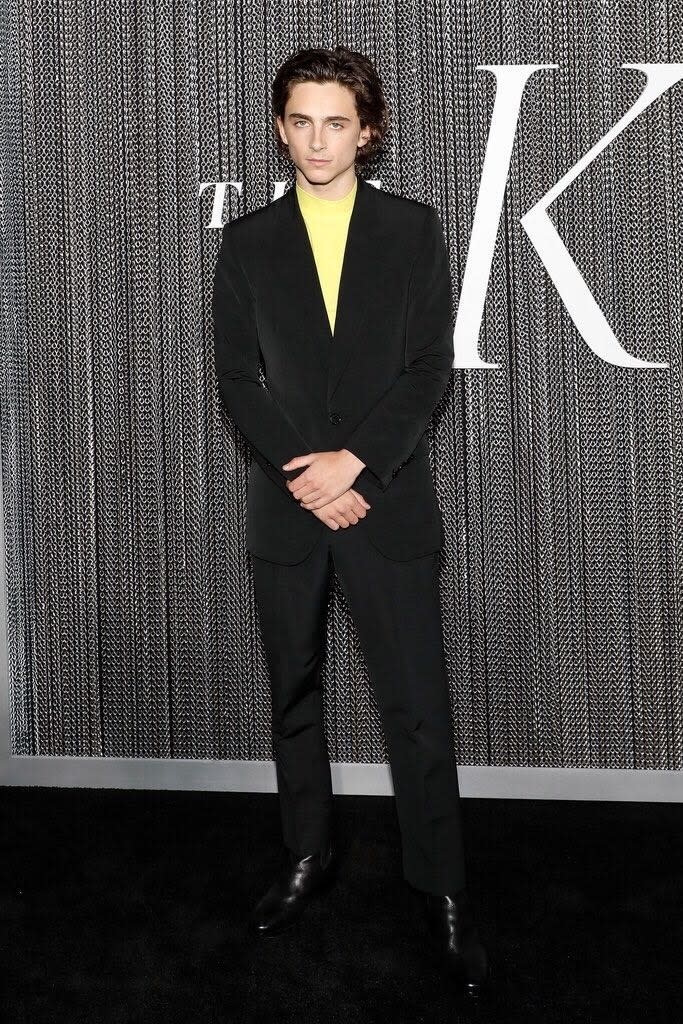

She’s built a small but powerful network of support among Hollywood actors, including Rami Malek, Chadwick Boseman, Idris Elba, and Darren Criss, and those relationships have meant that her men’s couture has been her biggest influence on menswear thus far. (More recently, contemporary menswear demigods Timothée Chalamet and Shia LaBeouf have worn looks from Givenchy's Spring 2020 show.)

Ashley Weston is Chadwick Boseman’s stylist, and she was putting together his wardrobe for the Black Panther press tour just as Waight Keller made her debut at Givenchy. Weston was a fan immediately. “She’s expanded the definition of black tie and of evening wear for men,” Weston said. “It’s so much more than just a suit.” Boseman was the first actor to wear Givenchy’s haute couture menswear—a spring 2018 tuxedo coat with a dazzling arrangement of silver beadwork and threads on the shoulders, which Waight Keller, Weston, and Boseman reworked together.

But it was Boseman’s look for the 2019 Academy Awards, where Black Panther was nominated for best picture, that was the real measure of Givenchy’s potential impact on the look of menswear. And challenging that perception was Weston and Boseman’s aim from the beginning. “I always thought it’s so puzzling that the definition of black tie for men was so restrictive and specific,” she said. Men’s personalities, she thinks, are much bigger than “ ‘Oh, this guy’s a black-tuxedo guy; this guy’s a navy tuxedo.’ ” Men, she told me, are “just as rich and expressive and varied as women.”

Weston put her finger on something that Waight Keller had brought up when she was putting together her ready-to-wear collection. “I don’t want to use this word feminine,” she said. “But there is a sensuality that softens that masculinity. And the genius of Clare is that she can mix the sensuality and softness of masculinity.… It still feels strong.”

Hollywood, a potent measure of masculinity, is also changing. “We’re getting into the period of time where no one’s [thinking], Okay, is this too feminine? Do we need it more masculine?” Male actors, Weston said, aren’t thinking, “ ‘I still need to look like this because I’m a leading man.’ That’s out of the question now. It’s almost like everyone is looking at things with more neutral goggles.”

It’s a complicated time to make any kind of proclamation about who you are as a man, or what masculinity is at all; to define it is to risk alienation. But clothing becomes the conduit to try new identities, to see what works, to discover what feels good. That’s the seduction of couture, the role of fantasy, the enduring enchantment that fashion holds over women. That door has never been so widely open to men. It’s just as Waight Keller said: “You don’t know you want it until you see it.”

Rachel Tashjian is a GQ staff writer.

A version of this story originally appeared in the November 2019 issue with the title "The Future Of Men's Fashion Is Female."

Originally Appeared on GQ