My frozen embryos are not children

The Alabama Supreme Court recently ruled that extrauterine frozen embryos are “children” under Alabama’s Wrongful Death of a Minor Act. As a result, the Court ruled that three couples whose frozen embryos were destroyed in an accident at a fertility center could pursue a wrongful death action. I have sympathy for the couples and their lost embryos. The destruction of an embryo when it happens in this way is a loss for which there should be some recourse (perhaps in a tort action for negligence), but extrauterine frozen embryos are not children.

When in the throes of infertility, the last thing I thought about as a real possibility was having leftover embryos. There are papers I had to sign informing me of the possibility, but it didn’t seem like it would actually happen. By the time my husband and I decided to pursue IVF, we had gone through two and a half years of actively trying—and six medicated IUIs with not even the slightest indication of a pregnancy. I didn’t think I was ever going to get pregnant and the thought of having too many embryos was so absurd, it was laughable. When my first retrieval produced 12 embryos and one of the first two embryos transferred resulted in a beautiful baby boy, I thought we might have to someday grapple with the issue of leftover embryos. But then, one by one, the embryos we had were lost (to the thawing process, to failed transfer, to early miscarriage), and we were back to square one.

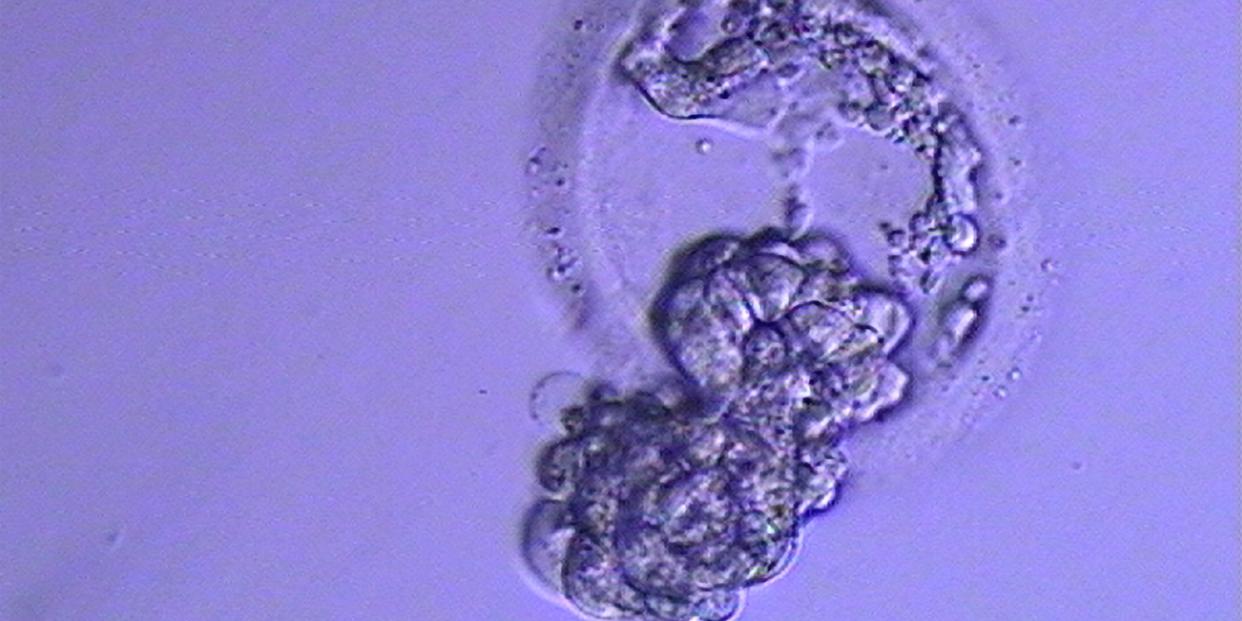

We went into the second retrieval wanting to get as many eggs and resulting embryos as possible because we had seen firsthand that more times than not an embryo does not equal a baby. Out of our previous 12 embryos, we had only one live birth, and we knew we wanted at least two more children, so the higher the number of embryos, the better chance we had of getting the family we desperately desired. We were shocked when more than 40 eggs were retrieved and more than 30 fertilized, becoming embryos. Three of those embryos resulted in live births, one was lost to miscarriage, three were lost in failed transfers, and more than a dozen were lost because they stopped growing or were not of good enough quality to freeze. I’m not even sure how many embryos we have left, but I know we have some, frozen somewhere in Michigan (not Alabama, thankfully) as blastocysts—each composed of 70 to 100 cells.

I feel paralyzed when I think about our unused embryos and what we should do with them. We ultimately have three options (unless that choice is taken away from us by the government): (1) consent to them being discarded; (2) donate them for medical research; or (3) donate them to another couple. Neither my husband nor I want the embryos discarded without them at least serving some purpose first, but we are conflicted about whether we should donate the embryos for research or donate them to another couple.

Well before the Alabama Supreme Court ruling, these leftover embryos forced me to give a lot of consideration to the question of when life begins. Being raised Catholic, I was taught life begins at conception, but that teaching is difficult to reconcile with the fact that out of 12 embryos from our first retrieval, only one resulted in a living, breathing baby.

Are our leftover embryos life as much as the babies that grew in my womb and were placed in my arms? Should I have grieved the loss of each embryo in the same way as I grieve my sweet Reed, who died when he was a month old? Although I did consider each lost embryo a loss, the loss was not the same in each situation.

The embryos that didn’t make it to blastocyst were a loss, but not as big of a loss as the embryos transferred that did not result in pregnancy.

The transferred embryos that did not implant in my uterus were a loss, but not as big of a loss as the embryo I miscarried at five weeks of pregnancy.

The miscarriage at five weeks was a loss, but not as big of a loss as the fetus I miscarried at eight weeks of pregnancy.

The miscarriage at eight weeks was a loss, but for me, it was not even remotely comparable to the death of Reed, who lived and breathed outside my womb, who slept contentedly on my chest, who looked up at me with his big dark eyes and saw into my soul.

I don’t know when my husband and I will be ready to make a decision about our frozen embryos, but it is a deeply personal one that we should be able to make without the government’s interference and without fear of legal repercussions.

I doubt that the Alabama Supreme Court Justices realize that most embryos that are created, both naturally and through IVF, will never develop into children. I doubt that they have ever mourned both the loss of an embryo and the loss of a child. I doubt they know the difference and I doubt they care. This decision is not about the sanctity of life. This decision is about reproductive control and will result in couples losing access to the medical treatment they need to grow their families.

Just as an apple seed has the chance of becoming a tree, it is not yet a tree. An embryo has a chance of becoming a child, but it is not yet a child.