Frida Kahlo wants to take a selfie with you

Walking into the Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving at the Brooklyn Museum, visitors are greeted by a floor-to-ceiling video clip of the artist staring into the camera. It was a little disarming because I came to the exhibit with some preconceived notions of not only her work, but of the artist herself. I thought it was all about the unnerving selfies with bombastic splashes of surrealistic color and symbolism. And maybe I thought I knew more than I did because I'd seen the Salma Hayek biopic from 2002. But that short video clip was a different entry point to the artist’s world than I'd expected. Like in her self-portraits, Kahlo was deliberately controlling what she wanted us to see by moving her head and body in small shifts, almost like she was creating a quick-study sketch on film instead of paper. But as I watched, I felt the camera was picking up so much more than perhaps Kahlo wanted it to, and so her deliberate movements were as if she knew the camera would give her away.

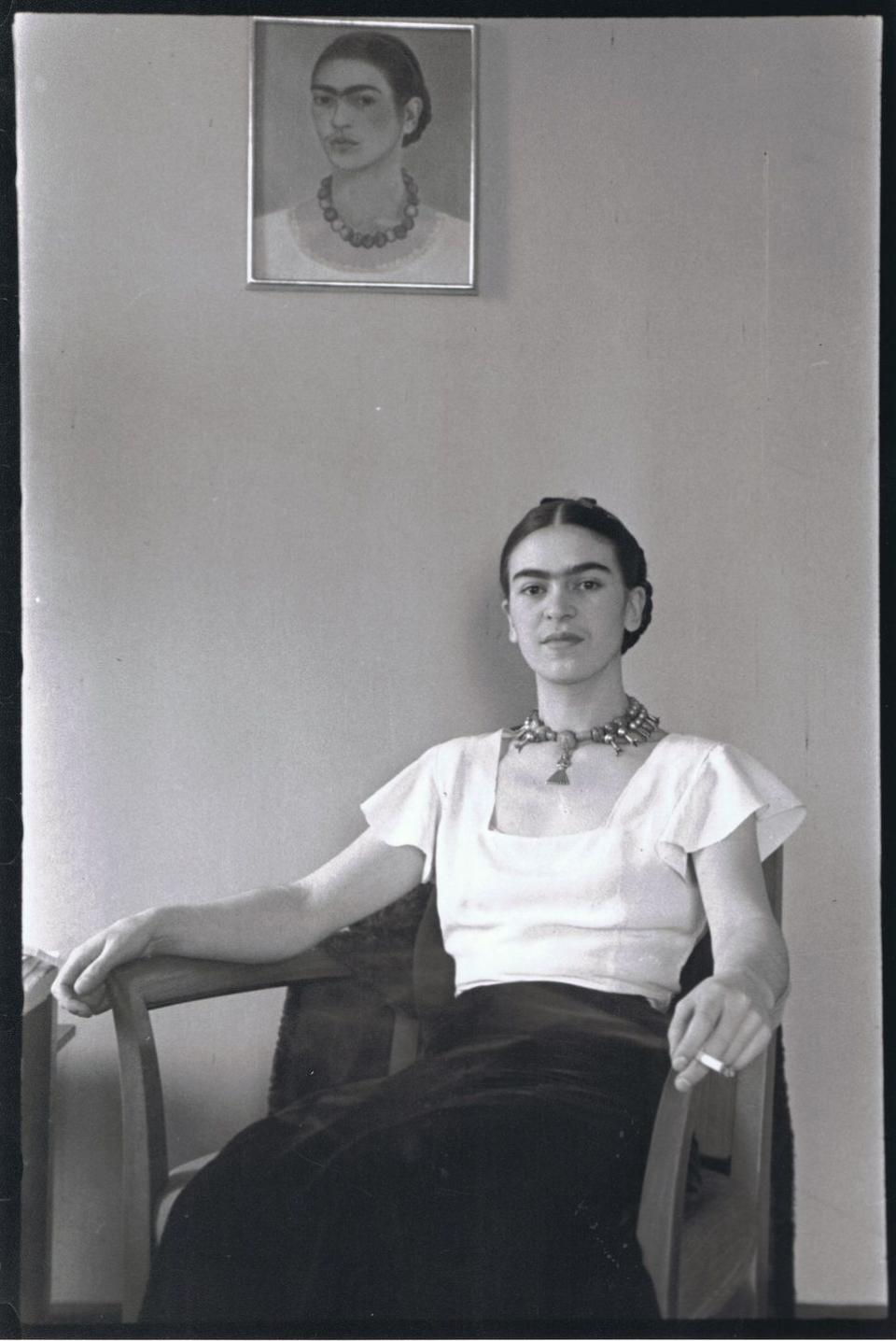

There are only a handful of her self-portraits on display, and yes, in person they are as unflinchingly direct as I expected them to be. These are no hipster selfies (no trout pout or duck face), but they are a tightly controlled expression of who Kahlo wants us to see. In a way they are just as “manufactured” in the same way rising Instagram stars might use filters and cropping, but Kahlo was working was in a time when women didn't always have control over their own image, or lives, so art was a way of controlling her “brand.” Frida Kahlo painted exactly who she was and aspired to be, and all the bits and pieces of that identity-braided hair, monobrow, layered gold jewelry, Techuano dress-are part of it.

Her obsession with identity was only natural. Kahlo was born in 1907 in Mexico to mixed parentage-a German-Hungarian immigrant father and half-Spanish, half-indigenous Tehuana mother-and she used that mixed ethnicity not only to define herself but also infused her painting with it. While recovering from a horrific bus accident that, among other things, fractured her spine and shattered her pelvis, she began to find her style as an artist. And as if being a working women artist in the 1930s wasn’t difficult enough, she became a member of the Communist party, famously hosting Soviet refuge Leon Trotsky in 1936. Her big break came in 1938, when André Breton, poster boy of the Surrealist movement, snagged a famous New York gallery put her work on exhibit-and New York loved her.

But this exhibition isn't really about her work-it’s more about the artist herself. Some visitors might be disappointed that more of her actual artwork isn't on display, but it didn’t bother me. I had very little art history education growing up, so learning about an artist gives me a frame of reference and helps me appreciate the work more. The exhibition features various photographs taken of Kahlo over a period of years as well as some of her jewelry, chest braces, a selection of clothing and bric-a-brac.

One early photo shows the artist in full Communion regalia, complete with white dress, veil, clasped hands in prayer, and a demure smile undermined by a pair of mischievous eyes. But here's the fun part: Years later she wanted to make sure no one would mistake this photo for a sign of true religious devotion, so she wrote “Idiota” on the back of it.

I wasn’t surprised how many times she was photographed-the camera loves her. Many of them were shot in and around her famous blue house and studio in Casa Azul, Mexico. Her poses and expressions have a bit more fluidity than her self-portrait paintings, but she still adopts her famous three-quarter pose in most of them.

The self-portraits dealt with the physical scars of her life: the bus accident she barely survived in her teen years; the polio that crippled her when she was only six; and her complicated relationship with husband, the Mexican artist Diego Rivera. The photos, on the other hand, are almost glamorous in comparison, like they could have come out of a 1940s Hollywood studio. And the vulnerability she doesn't paint, she shows to the camera.

The exhibit gave me the impression that Kahlo would have felt at home in today’s world of selfies and photo filters and would have definitely been an Instagram queen. At the end of the exhibit, visitors get to sit on a bench in front of a large blow-up of the artist staring directly into the camera. A moment of self-revelation for the visitor, maybe? I think Kahlo would have approved.

('You Might Also Like',)