How France and England nearly united to become the world's greatest country

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

There is right now an enhanced febrility to cross-Channel relations. Febrility in the domain is scarcely unknown – what with Napoleon, refugees and herring – but it is heightened by tension generated by the coming 90 minutes conflict this weekend. (Or 120 minutes, if things go according to no-one’s plan.)

This will have Kylian Mbappé in the Joan of Arc role, Kyle Walker as John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury and “Terror of the French” late in the Hundred Years’ War. Come late on Saturday midnight, one nation will be happy – which, these days, is already quite an achievement.

But all the anxiety could have been avoided if only France and Britain were one and the same country. It almost happened. In fact, it could have happened twice – the second time being the fleeting possibility that France and Britain would become one against the Hun in 1940. That was, though, a long shot.

More realistic were attempts at unity six centuries ago. Things actually went belly up exactly 600 years ago, in 1422, leaving us with one of the great “what ifs” of European history.

Then, England had been going pretty well in the Hundred Years War, following Henry V’s 1415 triumph at Agincourt. As all English kings of the time, Henry reckoned he had a right to the French throne. That justified the war. The tangled nature of dynastic relations between royals on either side of the Channel meant he had a reasonable case.

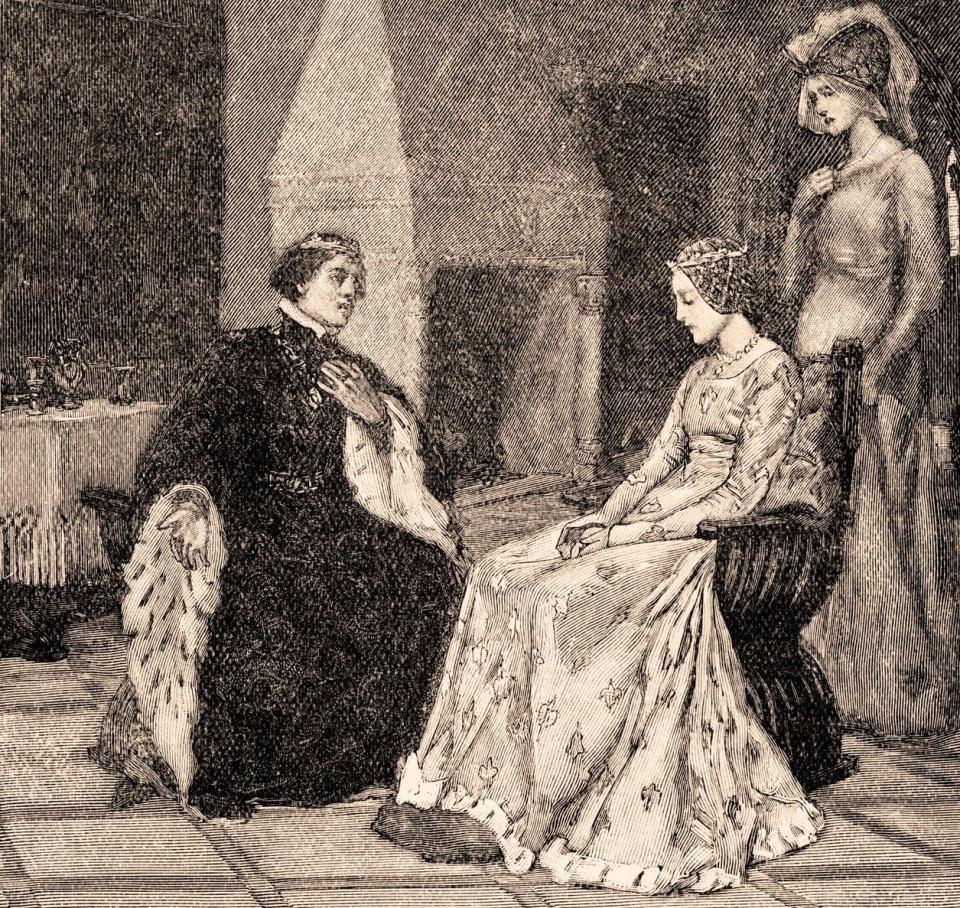

Oddly, to us, French king Charles VI agreed in 1420. He disinherited his own son in favour of English Henry. Henry would become French king on Charles’ death, the French throne then passing to Henry’s heirs. England and France would effectively be united for ever under English monarchs.

Tragically, “forever” lasted just a couple of years. Illusions of eternal concord shattered when Henry and Charles VI died within weeks of one another in 1422. So, instead of Henry V succeeding to the French throne, it fell to his son, Henry VI, to do so. Henry VI was nine months old, young even by French standards of responsibility. The resolve of Charles’ son – the Dauphin - to resist his disinheritance was stiffened, and then stiffened further when Joan of Arc rode in. Unusually for a 17-year-old girl, Joan took command of the Dauphin’s army, walloped the English at Orléans and Patay and led the Dauphin (another Charles) to Reims, as tradition required, be crowned Charles VII. Hopes for a dual monarchy, and imperishable cross-Channel harmony, frittered away. As, some years later, did England’s presence in France.

But, well, talk about a missed opportunity. A united Britain and France (Brance) would unquestionably have been the most powerful country in the world then – and conceivably still today. It would have escaped, or at least made short work of, all those wars which remain a bit vague in the memory (Seven Years, Spanish Succession, etc). It would have dodged the fisticuffs in the New World which sent Wolfe up the cliffs at Quebec and generated so much acrimony over Guadeloupe and Martinique.

Crucially, shorn of French help in their independence war, the American colonies would still be colonies. Or perhaps a crown dominion, thus a godsend for all. Who doubts that Mr Biden would benefit from the counsel of an older, wiser figurehead? As importantly, a united Brance would have avoided the French Revolution, English monarchs being already constrained by constitutionality. George III had Lord North, Charles James Fox and a pair of Pitts to contend with, rather than the pampered la-di-das in powdered wigs who flattered the Bourbons to absolutism, and whose heads were no great loss.

Constitutional government would have continued, rid of revolution and of Robespierre, and any tinkering with history is OK if it rids the past of Robespierre. Napoleon would doubtless have been prominent, conceivably as a member of Spencer Perceval’s foreign ministry. That might have saved Russia a lot of trouble, and also given Perceval’s assassin someone smaller to aim at.

Most vitally, both 20th-century world wars could have been avoided. A united Brance would have made Germany think long and hard about bursting out of the Vaterland. It is, in short, hard to dispute that, had the 1420 unification held, the world would have been a finer place.

And not merely in macro-historical terms. For a start, the world’s undisputed number one tourist destination would have been created. Granted, France is just that already, with 90 million visitors in 2019, the last year of normal travel. But, add in Britain’s 40 million and no other nation would come close. Plus unity would have a multiplier effect. Visitor numbers would surge. Obviously they would when in the same country – and without changing money (Brance would have retained the pound sterling) – visitors could take in the Orkneys and Corsica, Torquay and Cannes, Westminster Abbey and Notre Dame, Lourdes and Walsingham, Disneyland and Buckingham Palace, towers Eiffel and Blackpool – all washed down with Newcastle Brown or Château Petrus or, on very special occasions, both.

Nor would tourists, or anyone else, have to learn French which, by now, would have been marginalised, like Gaelic, thus freeing up study time to practise archery or musketry or whatever the modern equivalent might be. Internet hacking, perhaps. The Brance range of cheeses would have been unbeatable. Meanwhile, as the French adopted proper breakfasts, kedgeree and sandwich spread, so we would have stamped out andouillette and, being pragmatic, found a use for the rest of the frog. We would also have established, for the good of mankind, that bottled water is only useful if you’re a long way from a tap.

Entertainment-wise, I’ve a feeling that Johnny Hallyday might have been overshadowed by Billy Fury and would, like Billy, have faded out halfway to paradise, thus leaving room for the Stones, Deep Purple, Mott the Hoople and no-one at all from France. That said, France could certainly have satisfied the demand for anguished performers with complex backgrounds and a tendency to early death – Edith Piaf, Serge Gainsbourg, Dalida, Mike Brant – while Britain catered to the 20th-century taste for wholesome; Vera Lynn balancing Piaf, Cliff cleaning up after Gainsbourg.

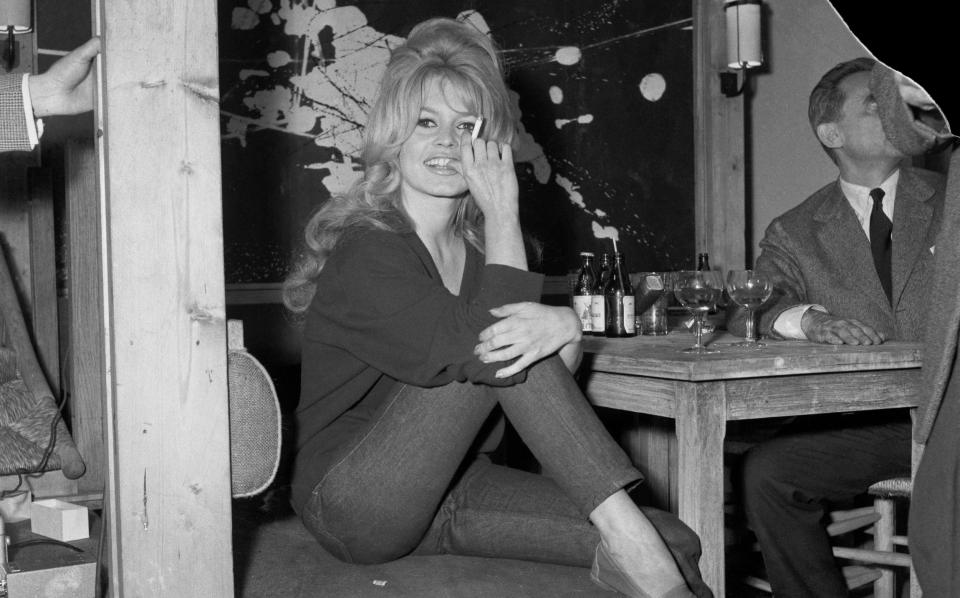

In sex-symbol matters, Brance’s combination of Brigitte Bardot and Diana Dors, Emmanuelle Béart and Elsie Tanner would have covered most essential aspects. Meanwhile, I can’t see Racine, Proust, Sartre and other examples of overwrought literary torture prospering in our united nation, not when there were Dickens, George Eliot and Mick Herron to hand.

In terms of transport, we would all have profited from the TGV and 2CV and everything in between, courtesy of French engineers. OK, they have nothing like a Rolls but, then, neither do the rest of us. Should we turn to inventions in general, Brance would be a world-beater, the French tipping in with aspirin, margarine, cinema, the parachute and the pencil sharpener to our trail-blazing of everything else, up to and including the hostess trolley.

In the field of sport, it’s obvious that if one teamed Anton Dupont with Joe Marler, southern hemisphere nations would be collapsing before the break. In earlier times, the French would have adopted cricket, thus learning fortitude and lawn maintenance. We would also have given them crown green boules. It goes without saying that Zinedine Zidane and Gazza would, between them, have boasted more ‘z’s than the soccer world could handle.

In fashion, we would have had a culture flexible enough to include the beret and bowler hat, brogues, kilts, the calf-length jupe-culotte and clogs. Finally, a united Brance would have meant that Britons understood the purpose of a bidet. Who can tell where such a breakthrough might have led?

Where to celebrate the English – in France

Despite the failure of Anglo-French union, certain spots in both nations exemplify our influence one upon the other. Among very many in France, they include:

Nice & Cannes

Rich Britons spent winter here on the Med coast, thus inventing the Riviera and modern tourism – all this despite the 18th-century Scottish writer Tobias Smollett, characterising the Niçois as “dirty knaves”. If Cannes and Nice, not to mention Menton and Antibes, now have an international veneer, well, we were the first in with the polish.

See our guide to the best hotels in Nice. EasyJet, Ryanair and BA fly direct to the city.

Biarritz & Pau

Other Britons favoured south-west France. The French of both Pau and Biarritz have clung to our golfing legacy. Pau has the oldest course of continental Europe, Biarritz 1907 memories of the only French pro ever to win the British Open. Arnaud Massy celebrated by naming his new-born daughter “Hoylake”.

See our guide to the best hotels in Biarritz. Ryanair offers non-stop services to the city from Stansted.

Calais

The port city had been English for 20 years – had sent MPs to the English parliament – when the French re-took it in 1558. Queen Mary was devastated. “When I am dead,” she said, “you will find… ‘Calais’ engraved on my heart.” This was in the days before the booze cruise.

Château d’Hardelot

Down the coast from Calais, the château celebrates cross-Channel friendship in general, the Entente Cordiale in particular. There’s much to see, including coverage of different table settings (a clue: French forks have their prongs down; English prongs are up).

Villeneuve-sur-Lot

Cradle of French Rugby League when, in 1934, following the English example of 40 years earlier, a handful of local rugby players grew sufficiently fed up of union’s violence and shamateurism to break away and establish the 13-man game in France. Villeneuve remains one of the few spots on the continent where one can enter a bar, order a beer and discuss Castleford and St Helens with people who know.

Read Anthony Peregrine’s guide to the Lot, including what to see and do and where to stay.

Cognac & Bordeaux

Blokes from the British Isles – Hennessy, Martell, Hine, Otard – put the international oomph into cognac while Britain has been a key market for Bordeaux wines ever since Eleanor joined us, bringing Aquitaine with her. The city remained besotted with Britishness – few upper lips were stiffer than those in the Bordeaux châteaux – until more recently getting in touch with its Spanish side.

See our guide to the best hotels in Bordeaux. Ryanair and EasyJet serve the elegant city.

Abjat-sur-Bandiat

The Dordogne throbs with British links and influence. Most importantly, Abjat, in the north of the département, is French HQ of conkers on the grounds that this is the only place in France where the game is played. The French National Conker Championships are scheduled in the village for October 1, 2022.

See our pick of the best hotels in the Dordogne. Fly to Bergerac with Ryanair.

Fontévraud Abbey

The greatest monastic complex of the middle ages is final resting place to a bunch of Plantagenet headliners. From their recumbent effigies, Henry II and Richard the Lionheart look miffed to be dead while, next to them, wife and mother Eleanor reads an improving work. English visitors flock. “One used to come dressed as a crusader, claiming to be a re-incarnation of King Richard and, as such, entitled to free entry,” Zoë Wozniak, a Fontévraud guide, told me. “He didn’t get it.”

Where to celebrate the French – in England

Among evidence of Frenchness in England – evidence you can visit, I mean – much is linked to folk finding refuge from foul play in France. Prime among these were the Huguenots, French Protestants fleeing Catholic persecution. It’s reckoned there were up to 100,000 in England in the early 1700s. Some claim that one sixth of the English population has Huguenot blood in their veins.

Spitalfields & Soho

Huguenot silk workers settled in Spitalfields. Soho took in gold and silversmiths and jewellers. As a passer-through wrote in the mid-18th century: “Many parts of this parish so greatly abound with French that it is easy… to imagine oneself in France.” See Spitalfields Square and the French Protestant Church, direct descendant of 16th-century Huguenot places of worship, on Soho Square (huguenotsofspitalfields.org).

Rochester

Home to the country’s only Huguenot museum, presently closed (huguenotmuseum.org).

Norwich

Another destination for Huguenot refugees. They wove, helped drain the fenland and, because of their foreign fondness for canaries, leant the town’s football club its enduring emblem.

Southport

Before becoming emperor Napoleon III, Louis Napoleon spent much time in England on the run from hare-brained political interventions in France. He travelled widely, including to Southport. The town’s arcaded main street apparently impressed him so much that he used it as inspiration for the creation of Parisian boulevards when he finally gained French power. Whence Lancastrian claims that “Paris is the Southport of France”.

Farnborough

Deposed in 1870, Napoleon III again fled for England, died in Camden Place, Chiselhurst. He was finally laid to rest in the crypt of St Michael’s abbey, Farnborough, an abbey created specifically for this purpose by his widow, Eugénie. She later joined him in the crypt.

4, Carlton Gardens

Another century, another refugee French leader in England. De Gaulle’s Free French were HQ’ed in Carlton Gardens: a 1993 statue of the general stands opposite N°4. He stayed and ate at the Connaught, when not with his family at 99 Frognal, Hampstead. From there, they all attended Mass at St Mary’s, a church founded by 18th-century French Catholics in London. Free French underlings headed rather for Soho – trad French assembly point in London – where the York Minster pub was renamed The French House in their honour. A glass of Picpoul de Pinet, which I recommend, costs £4.50.