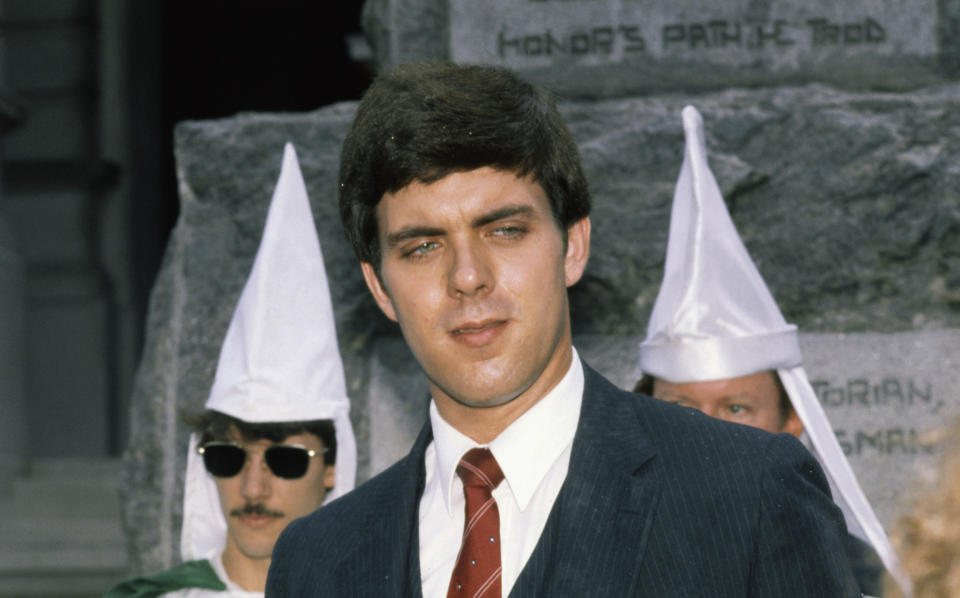

Four voices of white nationalism

To better understand the current spike in bigotry and hate in the United States, Yahoo News interviewed historians, sociologists, psychologists and experts who track and study hate groups. And we spoke to four individuals caught up in this movement. From a former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard to a 22-year-old ex-“social justice warrior,” each described a combination of factors that — despite their varying ages and diverse upbringings — led all four of them on the path to white nationalism.

_____

Gunther Rice, 22.

Gunther Rice was born and raised in southern New Jersey but now lives in Indiana, where he is training to be an electrician. Rice, who identifies as belonging to “Generation Z,” says his views are “more radical” than some of the older members of the movement.

Clad in a black bomber jacket over a black shirt printed with the words “Orthodoxy or Death” over the logo of the Union of Orthodox Banner Bearers, a Russian nationalist-fundamentalist group, Rice talked to Yahoo News at a diner in Pulaski, Tenn., the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan. Rice and other members of the white nationalist Traditionalist Worker Party had stayed in Pulaski following a White Lives Matter rally in Shelbyville, Tenn., earlier this month.

_____

In New Jersey, was the community you grew up in diverse?

Oh, very much so. They took a survey one time at my high school and there was 50 different languages spoken at home out of 2,000 kids. So for every 40 kids there was a new language spoken at home.

We had Somalis, Pakistanis, Ethiopians, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Guatemalans, El Salvadorans…

Was it a pretty integrated school?

Yeah, I mean, any time you get “integration,” quote-unquote, you always get certain cliques that form around where people are going to feel more comfortable.

There was very social-justice-oriented, sponsored days where you could get benefits and stuff for social signaling.

We had “be the change day,” for example. They’d get everyone in a room, basically, and it’s like, “all right, you can get excused from all your classwork for the day, free cookies and pizza, and listen, like, homosexuality and all these races, everyone is the same, everything is great.”

There was an agenda there.

Did you have mostly white friends or did you have friends of various backgrounds?

I’d say most of my friends were white but there were definitely a few Asians and a few Puerto Ricans and there were some blacks, yeah, that I was friends with.

Either in New Jersey or in Indiana, have you ever had any experiences where you felt like it was harder for you to get a job or accepted to college because of preference given to immigrants or people of other races?

If you are a high achiever academically, you’re still gonna generally get in where you want to get in.

I haven’t experienced as much academic discrimination just because I have always been academically excellent. But if you are, say, a white person who’s like in the middle, 3 GPA or something, statistically you will not get chosen over a minority with similar grades, even if they’re slightly below.

My personal case might not be the best example just because I have always been pretty academically excellent.

Your average white person, they’re all going to feel that a heck of a lot.

I am kind of like, I’m not white privileged but I am just, um, quite blessed in a lot of ways.

[Later, he comes back to this.]

Actually, you know what, yeah. There was one job I worked, it was like a cashier and a cart guy at a grocery store. It was when I was in high school and everything, so just minimum wage B.S.

So, the blacks at my work utterly got to slack off all day and it wasn’t hidden, you know what I mean?

Every single white person there would look at each other like — or heck, even the Asian people or the mostly-white Hispanics — we’d all look at each other and be like, “Yep.”

And then we’d get bitched out over just slacking the tiniest bit, just like, “Oh, you weren’t cleaning your register.” And then it’s like … one of the black guys will do something totally unprofessional, totally out of line, that no one else would get away with … it’s just like, “Oh, that’s just him.”

How did you get involved in the white nationalist movement?

I was a social justice warrior.

I was never quite anti-white and … I just realized that it is intrinsically anti-white, whenever you get into any sort of egalitarianism. That’s kind of one of my first red pills.

[The “red pill,” a reference drawn from the movie The Matrix, is a metaphor for awakening from a state of ignorance.]

Give ya an example. There’s a few hundred black people killed by cops every year, right?

Well, have you ever looked up interracial hate-crime statistics? If you look at the proportions of population, massively lopsided against white people.

[In fact, the FBI’s recently released report on hate crime statistics for 2016 found that 50.2 percent of hate crime victims were targeted because of bias against black or African-American people, compared to 20.5 percent of victims who were targeted because of anti-white bias.]

I’d bring this up to, say, a liberal group, and they’re like, “Well, they’ve still got white privilege. Yeah, she got gang-raped and burned to death but, you know, she still had the white privilege.”

And I’m just like, “Oh! So this isn’t really about equal, this is just anti-white. OK.”

Then I looked into that more and, about five years ago, I came across Stormfront.

I was never a part of the alt-right, I was never a libertarian. I think liberty is kind of gay.

So I just came to Stormfront … and I went, “Oh, OK … yeah, my school did teach me that! Yeah, you know what? Ever since I was a kindergartener, they do have an anti-white historical narrative! They leave out a lot of shit, don’t they?”

My mind was blown just by the hypocrisy I had seen.

How old were you at this time?

About 16, 17?

I was always very political and a very big history buff from a young age.

How did you get involved with the Traditionalist Worker Party?

Recently I was kind of introduced to the concept of activism and rallies.

I wasn’t really aware too much that rallies were a thing so I’m like, “Wait, there’s a bunch of white nationalists that go out in public and speak and do all this cool stuff and cool events? Hell yeah.”

So I went to Auburn when Richard Spencer spoke there. I went to Pikeville. I went to the first Charlottesville event, and then I went to the second one as well.

_____

Jimmy Mayberry, 24.

For Mayberry, who describes his small-town Indiana upbringing as “working-class white,” the ideals espoused by the white nationalism movement echoed the same values—“to be proud of my heritage” — that he’d been raised with. Still, it wasn’t until earlier this year that Mayberry began to channel those values into action, by getting involved with his local branch of the Traditionalist Worker Party (TWP).

_____

How did you get involved in this movement?

Really what it was for me was, I kind of let my life slip into just going off base urges and everything like that.

A lot of people in the movement came from past lives where it’s like we’re drug users, we’re just people who never did anything with life, and then we realized we’ve messed up our lives.

Coming to, like, the Traditionalist Worker Party, the League of the South, any of the other groups, the Nationalist Front or others, we’ve managed to get our lives on track. I feel like I actually have something in my life I can say I’m proud of.

How did you get connected with the Traditionalist Worker Party?

Internet culture. I reached out to a couple of other people in the party and then one day I asked about looking into who’s over in my area.

Back in January, I seen a video of [TWP founder Matthew] Heimbach debating with two leftists at Inauguration Day and I was like, “I don’t know anything about this group, but I know I gotta find out more of it. I don’t know if I’m even gonna join or not but these people seem awesome!”

What do you do for work?

I work eight hours a day at a factory.

I’ve always been working factory jobs and everything like that, because I started working in factories as soon as I graduated high school.

Actually, it’s one of the reasons I was able to learn up so much on the party. I had actually lost my job back in January and I was out of a job from January into July.

Up where I’m at, you get hired on at the factories and they either get the people they need and don’t need anybody else, or you just don’t get called back. So I was lucky that when July came around … they put me through because they needed the manpower.

I’ve always been working class white. At the same time it was like, “I’ve gotta have a job, otherwise I can’t do anything to help the party, help myself.”

So now you feel a sense of purpose?

Oh, yeah. Nobody wants to just set at home and do nothing. It’s not a fun feeling, you just waste away.

If you’re not working to something, what are you really doing?

What is your role in the TWP?

I help coordinate things in my area, down in southern Indiana. We’re still growing our numbers there as well so, I mean, it’s more or less whatever role I need to fill at the time.

How much of your time is spent on TWP activity?

I’m either away on party business every weekend or every other weekend anymore, it seems. And I have no problem with it whatsoever.

Do you agree with the idea [argued by Gunther Rice] that a white person has less chance to be hired or accepted to college if they’re competing against a nonwhite person with the same or lesser qualifications?

Oh yeah. I mean, I didn’t go to university, so there were a couple times where I know that if I apply for a job and if I get a black dude and a Mexican applying with me, they’re gonna be like, “Well, we’ve got a diversity quota and your credentials aren’t standing out enough.”

Have you had that happen to you?

No. But I said, I work factory jobs so it’s like, they go by if you can do the job.

What does your family think about your involvement in this movement?

My family actually raised me to be proud of my heritage, to be proud of who I am … so these ideals aren’t new to me.

But even still, my mother tells me every day, “I love and support you, you’re my only son, but I don’t agree with everything you’re doing.”

That’s fine, I don’t want them to be involved in it. If anything I do comes back to them, yes I’m going to feel awful but at the same time I stand by my convictions.

My family still loves and supports me. We’re an old Irish style family, you mess with one Mayberry, you mess with all of them.

_____

John May, 30.

Though he’s lived in east Tennessee for the past 10 years, John May’s white nationalist views are rooted in negative experiences he says he had growing up in demographically diverse Houston, Texas.

Covered in tattoos, including a Celtic knot on his neck and a small swastika on his hand, May is upset about what he believes is unfair media coverage of events like the deadly clashes between members of the alt-right and counterprotesters in Charlottesville this summer, and the September shooting by a Sudanese immigrant that killed one and injured several others at a church in Antioch, Tenn.

May spoke to Yahoo News at a White Lives Matter rally in Shelbyville, Tenn., earlier this month, where he said he hoped to draw more attention to the Antioch shooting as well as the recent influx of immigrants to middle Tennessee in general. He was accompanied by another rallygoer who, he said, he’d met in person for the first time in Charlottesville. Before that, the two had only met each other online.

_____

Do you mostly meet other people within this movement online?

A lot of our networking is done online, but I’ve met a lot of people through real life. The internet is pretty much the best route these days to find like-minded people.

How long have you been involved in the white nationalist movement?

I’ve been involved in identity politics for about 12 years.

I started out as a leftist. I was an anarchist and went into left-wing politics and socialism and stuff and realized, growing up in Houston, that the thing is, it devolved into identity politics.

You can’t just be a leftist and be for your people at the same time. Leftist politics are literally just multiculturalism and globalism. They think they’re fighting the system but they’re really just playing into the system

How did you make the switch?

I just read a lot and, like I said, just being a white man growing up in an area where you were pretty much attacked for being white, [I] have to come to the understanding that you have to stick with your own people.

To a certain degree, everybody does. Blacks do it, Latinos do it, American Indians do it. And it’s celebrated and that should be celebrated. Blacks and Latinos and everybody should be doing stuff for their people, we’re not disagreeing with that at all. It’s just white people should be allowed that same right.

Anybody else, like blacks and Latinos and everything, they can do that and not be labeled racist, but any time a white man stands up for his own people they automatically label him a Nazi or racist or hater.

What is the goal of your involvement in identity politics? What would you like to see happen?

I would like to see the creation of an ethnostate, although in reality that is kind of far-fetched. In my lifetime it probably won’t happen.

My family has been here since Jamestown. My family is native to here, essentially, and we just want white people to be able to stand up for white people and not be labeled haters or racists. We want a fair shake as everybody else gets a fair shake.

Is your family still in Houston?

They’re in Tennessee now. I have family that still lives in Houston, but my immediate family is in [Tennessee].

I’ve lost a lot of family members over my beliefs.

My cousins adopted Guatemalan kids, and I loved them as they were my cousins, I never had any issues with them.

But there’s so much hype, people get so brainwashed. Anybody who’s identitarian automatically gets labeled a racist or a Nazi so then … my cousins got in their head like, “Oh, he hates my kids.” And I’m like, “I don’t hate your kids at all.”

I’ve lost a lot of family members over my beliefs.

What’s your social network or internet forum of choice?

It was Facebook and then I’m kicked off of there.

Why?

For being identitarian. We can’t even have Paypals anymore. They’re blocking us out of everything, simply because of our beliefs. Paypal, Twitter, Facebook. … They’ve kicked us off of all forms of crowdsourcing.

We’re just wanting to preserve what America was and should always be, and that’s a place for everybody, essentially.

I don’t care if blacks live in America or Latinos live in America. I don’t want Mexicans necessarily moving into Tennessee because they’re not native to this area at all. If they want to stay in the Southwest, I don’t have a problem with that.

They [the media] are just taking us and they’re putting us into this narrative onto what we believe and the narrative is really not the predominant ideas that identitarians hold on to, you know, hating other people.

I don’t hate anybody. I’m a Christian, you know.

_____

Don Black, 64.

As a former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard and the founder of Stormfront.org, the first major online forum for white nationalists, Don Black represents the older generation of a movement that has become increasingly young and internet-based.

Over the past five decades, Black’s controversial views have gotten him into legal trouble, created professional barriers, and alienated members of his family — most notably his son, Derek, who renounced white nationalism in 2013. Still, every time he’s considered giving it all up, Black finds himself coming back to the conclusion that “It’s the right thing to do. We’re right.”

Black offers unique insight on how the movement has — and hasn’t — changed since he first got involved in the 1960s, and where he sees it going next.

_____

You grew up in Alabama, right?

I was born in north Alabama, near Huntsville, in Athens, Ala. After going to the University of Alabama, I moved to Birmingham. And I moved here, in West Palm Beach [Florida, where he currently lives] back in late ‘87.

What were your interactions with nonwhite people growing up?

In the town I grew up in, there wasn’t much racial tension. There was in Birmingham. I remember my daddy telling me we couldn’t go to the state fair this year “because the Negroes were causing trouble down there.”

My high school initially was all segregated, all the schools I went to, up until maybe junior high, was completely segregated. Then [former Alabama Governor] George Wallace introduced freedom of choice, so blacks that wanted to come to our high school could do so and the ones that wanted to stay in the all-black high school could do so.

So I never really saw full-scale integration of high school. The blacks that came to our high school were the ones that wanted to go to the white school and they didn’t cause trouble. We didn’t have trouble until the full-scale integration, which happened when I was a senior in high school.

[During the summer of 1970, before his senior year, Black was working on the gubernatorial campaign of segregationist and white supremacist J.B. Stoner when he was shot in the chest by a fellow Stoner campaign worker, Jerry Ray. Ray, the brother of James Earl Ray, who assassinated Martin Luther King Jr., was ultimately acquitted of shooting the teenaged Black, who he’d caught trying to steal membership records of Stoner’s National States Rights Party.]

I nearly died. My 17th birthday was three days into the hospital and my birthday present was getting taken off the critical list.

Anyway, I didn’t want to get into a big conflagration at my newly integrated high school, so I went to Huntsville, Ala., to Madison Academy, and that was pleasant. It was all white at the time. Not now, of course, but it was then.

Before you left your old high school, when it was partially segregated, did you have classes with any of the black students?

Yeah, we had black students, but they were all nicely behaved because they were the type that wanted a better education by going to the white school.

That was my high school experience. Of course, the University of Alabama had a contingent of blacks who were very — always tried to cause trouble with me. Just stuff like slamming the door in my face, stuff like that. They never actually challenged me to a fight or anything.

I had experiences with diversity in ensuing years. But initially, [his interest in white nationalism] was purely ideological. I started out as an anticommunist and was concerned about what I was seeing [in Alabama], even though I didn’t experience a lot of it directly.

In my little town … actually, everybody pretty much got along. I think we had maybe 10 or 15 percent black and, you know, they were, as my mother would call them and as all Southern mothers would call them, “the po’ old Negro that lived down the street,” that you felt sorry for, ’cause they worked hard and they didn’t have much and they didn’t cause any trouble. That was the Southern attitude.

Was that your attitude?

Pretty much, as far as where I lived. The neighborhoods were safe. When I was a little kid I could bicycle around town without having to worry. Could walk to school. There was never much crime. We literally were those people that didn’t have to lock their doors when they left home.

So your experiences with the black people in your neighborhood were never negative — you were just troubled by what you saw on the news happening other places?

Right, stuff like that. Of course, not being able to go to the state fair in Birmingham, stuff like that.

How old were you when you couldn’t go to the state fair?

10 or 11, and after that.

There was a lot of trouble in Birmingham. I would later live in Birmingham, but we didn’t go down there except for that annual state fair, which I really appreciated when I was a kid.

[The spring of 1963, when Black was 10 years old, saw the launch of the Birmingham Campaign, during which civil rights activists faced fire hoses and police attack dogs in response to peaceful protests against the city’s segregation laws with marches, lunch counter sit-ins, and boycotts.]

How did you first get your start in the white nationalist movement?

Many years before the internet, of course, back in the day, in 1969 when I was 15 years old, you actually had to find a mailing address and write. You know, the old-fashioned way. And a couple of weeks later they’d send you back a packet of literature.

Who did you write to?

There was the National Youth Alliance, that was actually the first. But Drew Pearson, who those of us my age would remember, he was a self-described columnist, muckraker. He wrote a series of articles about this sinister neo-Nazi movement which was thriving in the U.S. and they had influence in Congress and [prominent white supremacist and Holocaust denier] Willis Carto was the head of it. That piqued my interest.

[An example of Pearson’s reporting is here.]

I wrote the National Youth Alliance [a right-wing political organization also founded by Carto]. I found their address, they were in Washington, D.C., in Dupont Circle. I’d later visit them. I wrote to everybody, pretty much. I wrote to the National Socialist White People’s Party [previously known as the American Nazi Party], in Arlington, Va. I wrote to all kinds of people.

What about these groups sparked your interest? Were your parents proponents of these sorts of political views?

Not exactly. My parents were Southern conservative and I had become, by 14, anticommunist. I knew about groups like Liberty Lobby and the John Birch Society and the George Wallace for president campaign in 1968. I participated in that kind of peripherally, handing out bumper stickers in my hometown, stuff like that.

But I wasn’t completely convinced until I started writing to some of these groups. … I got the full story.

I grew up, of course, in Alabama and I thought the civil rights or so-called civil rights movement was tearing down the country and my state, so that motivated me to look further. By the time I was 15 I was looking further, and so I was interested in these other groups and what they had to say.

William Pierce [a physicist turned prominent white supremacist activist and author] impressed me because, for the previous few years, I had wanted to be a nuclear physicist and Pierce of course had been one of some accomplishment. He probably influenced me more than anybody.

[Black continued to pursue this path as he went to college, attempting to start a white student union at the University of Alabama, but failing to get a faculty adviser to sponsor him. His controversial activities earned him coverage in the campus newspaper, which, he said, impeded his progress in the military.]

I was in the basic ROTC program, and when I started making the campus newspaper, on the front of the campus newspaper, ROTC wanted to kick me out, even though they thought I was a good cadet. The professor of military science would even say that later I was a poster boy for them, but unfortunately I had all of these liabilities.

Later on I did enlist in the Army reserve.

When did you get involved in the Ku Klux Klan?

In ’75 I joined David Duke’s [Knights of the Ku Klux] Klan. I’d been reading about him, but I already knew him for years.

There’s actually a New York Times article about a rally that he held outside of Baton Rouge with, I think they said 2,700 people, which was huge by our standards, to actually get that many people to an indoor rally. So that piqued my interest, David’s accomplishing something.

[In fact, the 1975 Times article Black seems to be referencing states that, according to the FBI, Klan membership had dwindled from 17,000 in 1976 to only 1,700 across 15 Klan groups nationwide. Duke, then 24-year-old Grand Dragon of the Louisiana-based Knights of the KKK, reportedly disputed the FBI’s statistics, telling the Times, “We had almost 3,000 people at our rally in Walker, and most of them were members.”]

What was your impression of the Klan when you were younger, growing up in Alabama? Did you ever think you’d become a part of it?

No. We had a Klan Klavern in Athens that I had heard about, but I hadn’t considered joining because they just didn’t seem to have the intellectual wherewithal. I didn’t consider joining the Klan until I heard about David.

What was it about David Duke that appealed to you?

I knew David, I knew that he understood everything, and the fact that he was getting so many people at his rallies was impressive. So that’s the reason I went down and joined up with a couple of other friends, three other friends from Alabama, one of whom would become my wife later. And then ex-wife.

[Black’s current wife, Chloe, was previously married to Duke. ]

What did your parents think about you joining the Klan?

They weren’t hostile. They had met David too, and they weren’t hostile but they thought it was a really bad idea for me to be getting all this attention. They thought it was dangerous.

They were never completely happy about it. My father was a little more accepting. They came over to our side, or my side, intellectually after a while. But they thought that it was, particularly my mother thought that it was dangerous in various ways, so she was never happy about that.

What about your siblings?

I have a big sister, 12 years older than me. She’s not exactly on our side but she’s … a Trump supporter.

[Over the next 12 years, Black gained prominence as a leader of the Alabama chapter of Duke’s Klan. In 1981, he and several other white supremacists were arrested by federal agents before embarking on a plot to invade the Caribbean island of Dominica by boat and violently overthrow its black-run government. Black spent three years in federal prison, where he learned the computer programming skills that would later help him create Stormfront.]

[Though he finally left the Klan in 1987, Black continued to work on Duke’s perennial political campaigns, even after relocating to West Palm Beach, Fla.]

I’ve lived here as long as I’ve lived anywhere, but I never intended to stay here.

I was going to stay here about five years and make my fortune and then move back to Alabama. But I didn’t make my fortune and so I’m still here. I’ve kind of given up on the fortune, actually.

[Black explains that he’d hoped to become a stock broker but failed to obtain his brokerage license, a decision he says was made by Florida’s “Jewish comptroller” based solely on his reputation and affiliation with David Duke. In lieu of work, Black says, “I devoted myself full-time to political activity.”]

I actually started Stormfront as a dial-up bulletin board shortly thereafter, in 1990. During one of the David Duke campaigns, the follow-up campaign when he was running for U.S. Senate, as a very small bulletin board.

What were your initial traffic numbers?

About 500 a day. Back then it was [pretty good]. And that was without any kind of advertising, or not much. That was just from search engines.

What’s your membership now?

We get about 50,000 user sessions a day and there are over 300,000 registrations, most of which are not active, of course, but we have accumulated that many. So it’s still fairly active.

Of course, we were down for a month after Network Solutions [Stormfront’s domain registrar] decided that we were in violation of their terms of service for having the wrong political views. This was in the aftermath of Charlottesville.

I was finally able to wrestle it back from them but they had frozen it, they had locked it, I couldn’t get it back, couldn’t get the domain back initially. We’re kind of back to where we were, but not quite. We’re actually nowhere near back to where we were right after Charlottesville. We had a big spike — our traffic doubled after that.

Stormfront really popularized the term “white nationalism.” What does white nationalism mean to you?

It means racial, white racial nationalism, as opposed to civil nationalism such as what is promoted by Donald Trump and other groups. They disavow any kind of racial aspects to nationalism, but nationalism has traditionally been a racial movement.

Nationalism is not about diversity. It has racial underpinnings and we understand that and we think we have the right to maintain that, at least some portion of this country, as a white nation with a government that reflects the values of our race. Of course, other races feel they have that right, and they don’t come under all of the criticism that we do.

I’m very happy that after we used that term for so many years, whereas the mainstream media would always call us “white supremacists,” now suddenly “white nationalist” is almost as popular as “white supremacist.” I guess we can thank Hillary Clinton for that, back during the campaign.

For whatever reason, at least we’ve made a step upward. White nationalism is much more descriptive than white supremacist. Most people I know don’t consider themselves supremacists. Separatist, maybe, and nationalist.

What do you think about the term “alt-right”? Do you think it applies to you?

That’s a term popularized by Richard Spencer, whom I also know. He didn’t invent it, but he popularized it.

We’ve never used that term, although we’ll accept it. We’ll take it now.

Alt-right was considered a little too [inclusive ] a couple years ago. They had gay speakers. Richard Spencer had this guy [Jack] Donovan who’s openly gay, brags about it, which is just a little too inclusive for most of our people.

That’s kind of what we associated it with. It was not as hardcore ideologically. But now that it’s become popularized, we’ll take it, but we don’t use it very much.

It does take the edge off the racial terms, whether it’s “white supremacist” or “white nationalist.” Just the term “white” has become a term of derision nowadays. You can’t even use the term “white” without offending people. So alt-right, I guess, does have an advantage there. But it’s kind of ill-defined.

What do you think of the new generation of white nationalists, and the state of the movement in general right now?

I think we’re definitely making progress, and the alt-right, whatever it is, is part of that.

Does this stand out as a significant moment for white nationalism?

I think there are more people now involved than ever before. I don’t know about the ‘60s, back when I was just getting started. There were some fairly big meetings back then with other groups, like the National States Rights party and the Klan.

All of that went into rapid decline and by 1970 I thought we’d really hit the pits. I didn’t think it could get any worse, but it did.

Today it’s different. There are quite a few people … in Charlottesville, there were a lot of people there. More so than I think was reported.

Were you in Charlottesville?

No. I’m glad I wasn’t there too. I’m a little bit disabled now. I had a stroke 9 years ago, so I wouldn’t be much good in a fight.

Trump was absolutely right when —he was absolutely wrong because our people weren’t there to start a fight—but he was right when he said that the other side had people there that were violent. They were.

But even then, it’s a pretty big turnout. So we’re seeing more and more of that, and I think we’ll continue to see that.

What do you think is the reason for this recent resurgence?

Zeitgeist. It’s a sign of the times, the spirit of the age.

Of course, immigration motivates a lot of people. And of course Trump has inspired a lot of people.

What’s next for the white nationalist movement?

We want to go beyond Trump. Trump has been a disappointment for a lot of our people. He is, at least, raising awareness about immigration, to a degree. Even though it’s kind of a civic nationalist awareness of immigration. He thinks that it’s OK to bring in third world immigrants as long as they’re properly vetted. But he does want to end the diversity lottery, so he does give us a little bit of hope.

He has divided the country, which might be good.

We have never had a more racially polarized country than we do now. I mean, we have antifa [i.e., far-left-leaning militant groups] smashing things and beating up Trump supporters, and Trump supporters stockpiling guns. So I’m not sure who’s going to win.

Does that concern you?

I don’t want to be in the middle of it, that’s for sure. And I don’t want our family to be in the middle of it.

What would be the ideal outcome of all this?

I think separation will solve the problem. I don’t know exactly how that’s going to turn out, but as I said earlier, I think we have the right to have at least some part of the country that represents our people, our values. A government representing our agenda.

I think that will happen by, for lack of a better word, balkanization. I think our people are voting with their feet. They are moving to other parts of the country even though there’s not really a place to run right now, but there are some places. We’re not going to stay in south Florida much longer.

Where are you going to go?

East Tennessee. We already have family who’ve moved there and we’ve been holding our conferences there for seven years. We’ve had other people move there as well, so it’s one area.

There’s Harrison, Ark. We visited there recently, and we have friends who have lived there a long time. Similar type place, along with Branson, which is nearby.

The ethnostate, which is the term the alt-right likes to use now, and it’s legitimate, is the ultimate goal. I don’t know just how this is going to play out. It’s not going to come immediately, but I think it can come.

Do you think you’ll live to see the creation of an ethnostate?

Will I live to see it? Who knows. I don’t know how long I’m going to live. But I think it will likely happen.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: