In the hands of Trump, the past is a political weapon

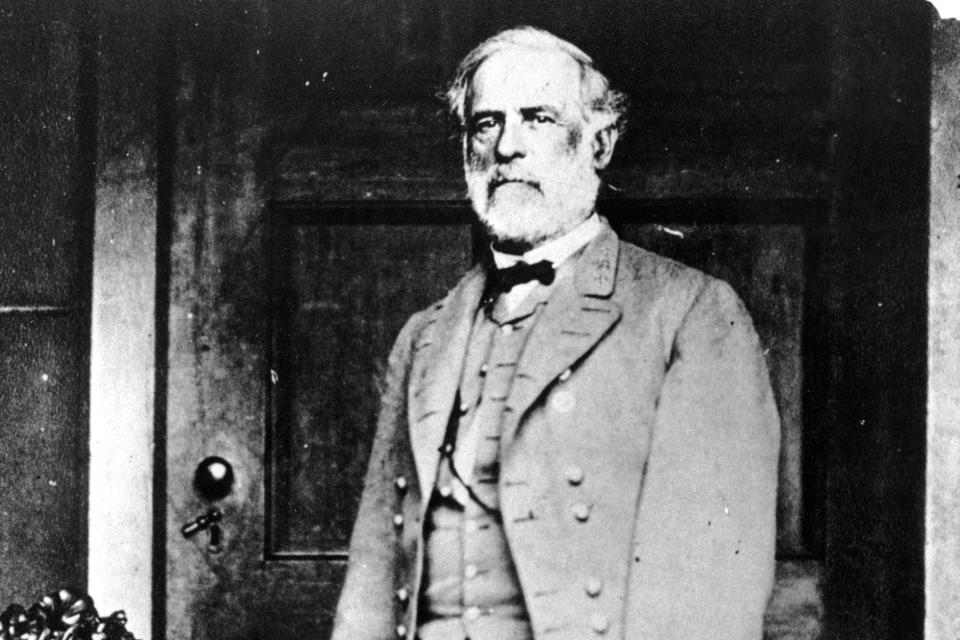

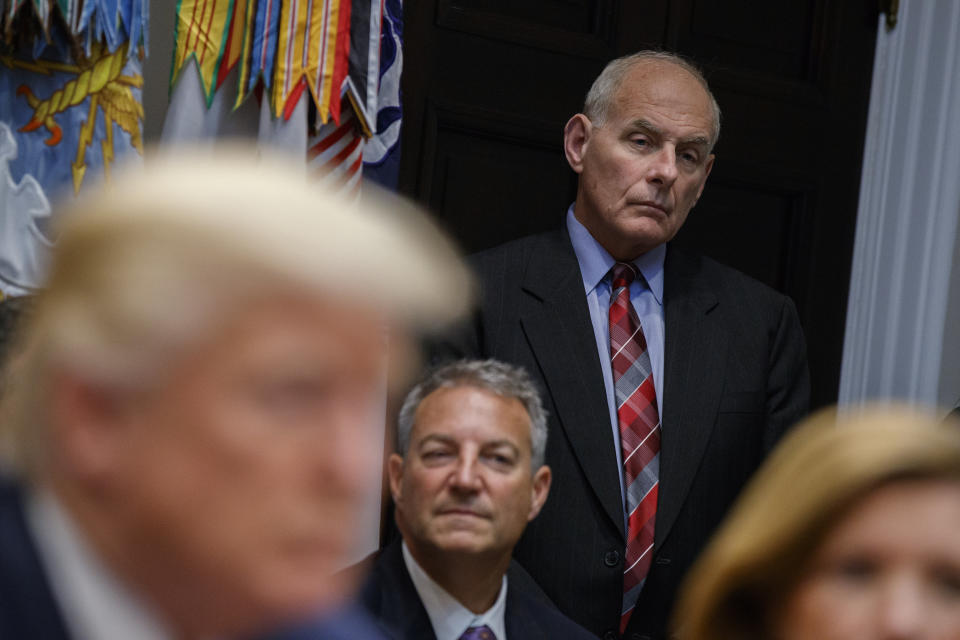

At the White House press briefing Tuesday, spokeswoman Sarah Sanders defended Chief of Staff John Kelly’s remark that the Civil War resulted from a failure to “compromise” by both sides. Kelly told Fox News that Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee was “an honorable man” who “gave up his country to fight for his state, which 150 years ago was more important than country,” and that “the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War, and men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand where their conscience had them make their stand.” Historians called this view “strange” and “highly provocative,” but Sanders, defending Kelly, told reporters, “Because you don’t like history doesn’t mean you can erase it.”

An uproar about the causes of the Civil War shouldn’t surprise people who have been following Trump’s White House. The president, the chief of staff and other senior White House aides have established a pattern of using history — especially issues of race and “heritage” — as political weapons, promoting historical myths popular with Trump’s overwhelmingly white base of supporters.

Using history in the service of politics is not inherently a bad thing. Every politician — virtually everybody in elective or appointed office — invokes the past at one time or another to advance a policy, justify legislation or score points with voters. Politicians, understandably, view their decisions on hard issues through the lens of their own experiences and their interpretations of the past guide their sense right and wrong.

And the use of history can indeed illuminate some complicated policy debates. During the 2001 debate over President George W. Bush’s trillion-dollar-plus tax-cut plan, for example, Democrats argued that Ronald Reagan’s 1981 tax cuts ultimately yielded much higher federal deficits, evidence against the proposition that cutting tax rates would stimulate the economy to the point of actually increasing revenues. They weren’t wrong. During the 2002 debate about the congressional resolution authorizing the use of force in Iraq, some war opponents warned that invading Iraq would lead to another “quagmire” like Vietnam, a war in which more than 58,000 Americans died.

These are debates worth having. Why did the U.S. lose the War in Vietnam? What were the roots of stagflation in the 1970s? What triggered the economic expansion of the Clinton years? These legitimate questions can illuminate policy discussions, even if they yield complicated answers. But comments about the Civil War coming from the administration constitute something altogether different and even downright dangerous.

As Columbia University history Stephanie McCurry told the Washington Post, Kelly’s remarks track very closely with “the Jim Crow version of the causes of the Civil War” and “all of the major talking points of this pro-Confederate view of the Civil War.” Kelly’s comments are also “profoundly ignorant,” as Yale historian David Blight succinctly put it. The South seceded and waged war against the North to defend their power to enslave millions of African-Americans, as historians have shown through decades of scholarship.

Kelly and Sanders’s comments also reflect an ongoing Trump-sanctioned effort to weaponize history to rally white conservative voters on behalf of the most embattled first-term president since the advent of polling. Recall that in February 2016, Trump told CNN’s Jake Tapper that he wouldn’t reject the support of former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke. Trump gave as his rationale, “I know nothing about white supremacists” or David Duke, and he had to study them first before saying or doing anything. (He did eventually “disavow” Duke’s support.) But his refusal was actually a way of invoking the Klan’s history as a white supremacist organization that conducted a reign of terror against African-Americans in the 19th and early 20th centuries to appeal to white Southerners who still harbored racist views.

Trump has argued that in the recent past the politicians have sold out the U.S. to foreign countries (Japan and Germany in the 1980s; China and Mexico today), enriching political elites while Americans suffered. When Trump became a leading advocate of the preposterous charge that President Barack Obama was not born in the U.S., he sent a clear message to some of Obama’s most ardent critics (who would become Trump voters): the nation’s first African-American president was not a natural-born citizen and thus ineligible to be president. Trump was drawing on a shameful history in which white Americans denied the rights of African-Americans, treating them as less than full citizens, to promulgate the idea that an African-American should not be the leader of the free world.

Under the Trump administration, history has become more than a reference point in arguments about policy; it has become the equivalent of Teddy Roosevelt’s “big stick,” which Trump uses anytime he feels threatened politically. Trump and his team twist facts and distort reality about some fairly basic questions of the American past for the clear purpose of ensuring that Trump’s overwhelmingly white base stays loyal to him. It gives cover to a White House under siege from prosecutors, the press and a large majority of the electorate opposed to his conduct in office.

Matthew Dallek, an associate professor at George Washington University’s Graduate School of Political Management, is the author of Defenseless Under the Night: The Roosevelt Years and the Origins of Homeland Security

Read more from Yahoo News: