Former American Idol Co-Host Brian Dunkleman Opens Up About Everything

Welcome to Basic TV Week, a celebration of all the bad, perfect, and (mostly) network television we can't get enough of.

At the peak of American Idol-mania, when folks were feverishly dialing a toll-free number to vote for Ruben Studdard, Fantasia Barrino, and Carrie Underwood, Brian Dunkleman nearly packed up and left the United States.

Consider his predicament: For a brief moment, he was Ryan Seacrest’s equal, co-hosting Idol in its inaugural stateside season. He had a front-row seat to Kelly Clarkson morphing into a superstar, and Simon Cowell becoming a taste-making super villain. But Dunkleman was miserable. He never wanted to be a host; he wanted to be an actor and comedian. So he left, and then the show became fully synonymous with the country’s warped, early-2000s ideation of the achieving American Dream. Dunkleman says he “couldn’t open a newspaper, a magazine, listen to the radio, or go online” without being confronted by Idol and the fortune that would’ve been his if he had just sucked it up and stuck it out.

Except, if he hadn’t quit on his own accord, he was going to get canned. The Idol producers had concluded after Season One that Ryan Seacrest should be the only man for the hosting job. But for almost 15 years, no one—not even Dunkleman—knew that to be indisputably true. Bystanders just thought he was an idiot. Or, as Dunkleman’s Twitter bio used to read, a “television history footnote.”

Dunkleman, now 47, is the announcer of Family Feud Live: Celebrity Edition, a tour-oriented version of the popular TV game show. He lives in Los Angeles, recently launched a Patreon, and has dipped his toe back into standup after an extended hiatus. As TMZ revealed earlier this year, he’s driving for Uber, a move he says was necessary to support himself (and his son) in the midst of a divorce and custody dispute. After the TMZ story broke, Dunkleman found himself in an unfamiliar position: The Internet was defending him, like it defended former Cosby Show actor Geoffrey Owens, who was “caught” working at Trader Joe’s. “I had a groundswell of people that I knew and had never even heard of defending me,” Dunkleman says. “It was the sort of thing that renews your faith in humanity.”

During our hour-long conversation, Dunkleman’s faith in humanity seems to wax and wane. He talks glowingly of Paula Abdul, of various behind-the-scenes Idol figures, and he seems acutely in-tune with his circumstances—past and present—blunting the harsh impact of his stories with self-deprecation. But he also tells me “there are a lot of fucking assholes” he’s had to deal with over the years, like the two guys he paired up with to play a round of golf years ago, who waited until the fourth hole to ask he used to host Idol—Dunkleman responded in the affirmative, which led to one of them pressing him on whether he realized he’d be a multi-millionaire had he only stayed on past Season One. “Like I never even considered that while I’m playing on a shitty public course with this dude,” Dunkleman says.

Given the tumultuous nature of his last few decades, and the incessant interview requests he gets, it’s hard to blame him. “I understand the interest in Idol,” he says. “It’s the only reason you and I are talking right now. But it wears on a man, and the most annoying part is people reminding me of how wealthy Ryan Seacrest is. I know.” In light of the tabloids picking up his Uber-driving side gig, Dunkleman agreed to talk to GQ to try and once again clear the air about a little bit of everything—including his Idol days.

GQ: You auditioned three times in two days for American Idol, right?

Brian Dunkleman: Yeah, I came in really late in the process, and apparently they had seen 3,000 people. It’s funny—I had made a decision with my reps that I wasn’t going to host any stuff anymore, because acting was my career trajectory. I had just done Friends, I had a development deal for my own sitcom, and as it turns out, somebody from Fox was in the room when I pitched my sitcom. He remembered me and wanted me to come in to audition for this, so I was like, “Alright, fine, I’ll come in.”

The audition was all improv, and they asked me to stick around afterwards. You know you have those crossroads in life that change the entire course of your existence? I almost left while waiting around because they ran out of $8 parking validation stickers. I stuck around, auditioned again for the executive producers, tested again with this guy named Ryan Seacrest, and that was it. The next day, we were working. We were just thrust together like, hey, you guys have never met, go make chemistry. That’s not easy to do.

American Idol Finale

Kevin Winter/ImageDirect/Getty ImagesYou’ve spoken about being immediately uncomfortable with the Idol auditioning process. What was the first thing that made you feel uneasy?

On the first day during the L.A. auditions, we’re outside the judges room in the holding area. We’re not really seeing what’s going on inside. Ryan and I are spending time with these kids as they go in. We’re getting to know them a little bit, meeting their parents. It was fun for about an hour, and then there was a stretch where the whole energy shifted. These kids were coming out of that room bawling one after the other. It was really jarring. I thought, what in the fuck is happening right now? Like, when you’re talking to a girl and her father, who had just sold a bunch of things, and they were living in a truck just to give her this chance, and then she comes out of that room with dead eyes…I think about that girl a lot. It got so bad that I went and excused myself and found somewhere to hide to process everything.

Did you have a favorite contestant from Season One? Or did you try to stay impartial?

I tried to stay impartial, but I really did love Tamyra Gray. [Ed. Note: Gray finished in fourth place.]

Kelly [Clarkson] I could immediately tell was a genuinely good person, and it was really cool to watch her blossom into a star. There were a couple performances where I was like, “Wow, this girl is good,” and there was one in particular where I was like, “Yeah, she’s a superstar.” Some of the contestants I’m still in touch with on Facebook.

American Idol

Kevin Winter/ImageDirect/Getty ImagesAny fond memories from your time on Idol?

My favorite part of the tour was in the mornings. Me and Ryan Seacrest would just go out into the city and find funny stuff to do. Of course, they hardly used any of it.

I was going to say, I don’t really remember that.

We were in Texas and saw a gas station with a tiny, shitty swimming pool. So immediately, we do a tight shot of me and Seacrest laying next to the pool, and we were like, “They put us up at the greatest places here on the tour. This is living.” They never used that. There was also a scene where we were hanging out at the beach in Miami, and it’s just Seacrest and I from the shoulders up talking about auditioning or whatever, and as you pull back, we’re rubbing lotion on a couple of old Cuban guys’ shoulders. They didn’t use that either.

I watched a local news interview you once did, where you said you cared comedically about what people thought of you, and that affected how you felt about your experience on Idol. What does that mean, you “cared comedically” what people thought about you?

Our scripts were written by the executive producers, and they didn’t translate to what I felt was American comedy. I’ll just come out and say it: It was really cheesy and really corny. When you’re a comedian, you don’t have anybody else controlling anything that comes out of your mouth. So to pass these “jokes” off as my own, it was really difficult. I don’t know what other show on television of that magnitude doesn’t have writers, but they didn’t have writers. I begged and I begged and I begged—I was working my ass off trying to punch up every script, and towards the end of the season, I hired three friends of mine who were comedians. I would give them the scripts as soon as I got them. How many intros for Randy Jackson can one person think up, you know what I mean? These guys would write some jokes, and then I’d come in and pitch them last-second. I didn’t tell other people, but I spent a lot of money out of my own pocket, because I cared about the show and my perception. You build a career as a standup comedian, you don’t want to be known as cheesy and fucking lame.

When you did the Idol reunion show, I understand some of the longtime producers told you they probably weren’t going to bring you back after Season One, and you had essentially just beaten them to the punch by quitting first.

I was told that flat-out by three of my old bosses. One of them was Simon Fuller. He said, “We realize it wasn’t fair to you, and we kind of threw you to the wolves. We realized you didn’t have any hosting experience, but we thought you were really funny.” He was genuine, and I really appreciated it. I was told by one of my old bosses that it came down to whether to keep both of us or go with one host. They decided to go with one, and obviously I wasn’t the one. They told me that I quit before they could deliver the news. I didn’t know that. Did I have my suspicions? Did I see the writing on the wall? Of course I did. I’m not stupid.

But still, to tell you that I gained closure is an understatement. All those years where I’m walking around as the biggest mistake in the history of show business, it turns out that’s not what happened. That’s going to allow me to die peacefully someday. It’s changed my whole outlook on everything. Thank God that I went and did the reunion show. My manager and agent at the time told me not to, but I told them, “I have to, I’ve got to face this.” Like, I went into hiding to get people to forget I was on this show. That’s the actual big mistake I made.

When you went into “hiding,” did you view that as a strategic decision? Or was it driven more by stress and anxiety?

Stress and anxiety had something to do with it. It had a lot to do with the fact that my goal was to have a successful acting career, and it’s really hard when you’re on a stage introducing yourself as the former American Idol host. I figured enough time would go by and people would forget it. It’s a double-edged sword, because here you are wanting to talk to me. It’s been a long fucking time. Every year people want to talk to me. It really blows my mind. I can’t believe anyone still cares, to be honest with you. But there seems to be some fascination with the fact that I did go away.

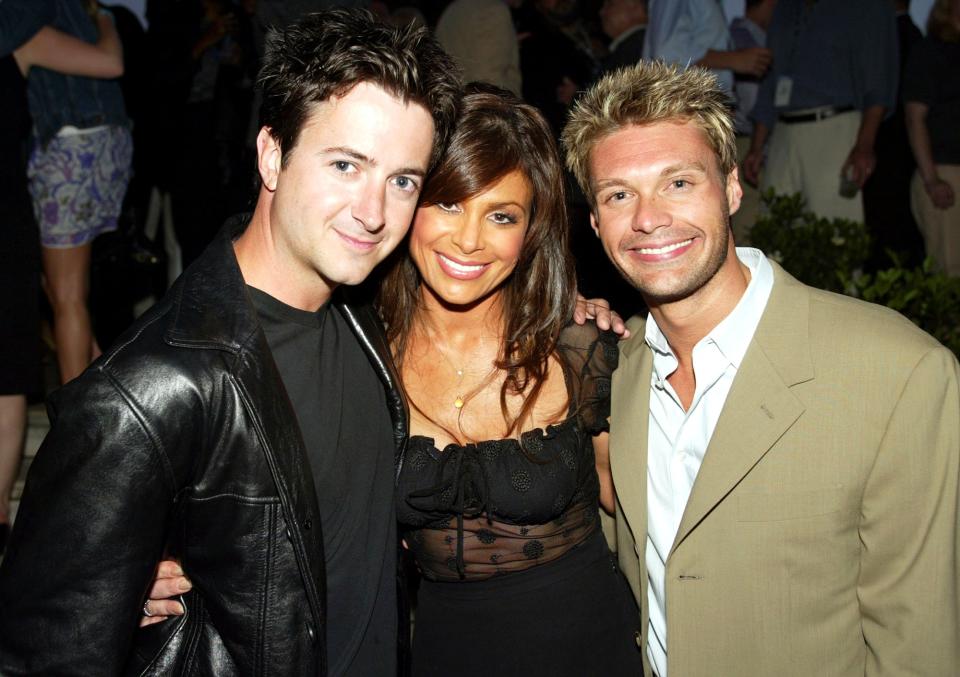

Fox Network's TCA Summer Tour Party

Kevin Winter/ImageDirect/Getty ImagesI never got into this for fame or money. I got into this because my goal in life was to experience as much joy as I could while doing the least amount of work. Maybe that’s because my dad died at work when I was 11 years old. Who knows what that did to me psychologically? But I made the decision very early: I’m not going to live to work; I’m going to work to live. I started doing standup at 20 and was like, “This is fucking fun.” That was it. I dropped out of college. Collaborating to make something good is what I love and what I want to do. Unfortunately, I got to do that more before Idol than I have since.

What was your reaction when you first saw the headlines about you driving Uber earlier this year?

My girlfriend is the one who contacted me about it. I remember looking at the TMZ headline and not feeling anything. I knew it was going to happen, and I had already made the decision to disclose it. I can’t give any details about it, but I was part of a television show where I divulged the fact that I was Uber driving. I don’t know if it’s even going to air, but whatever.

So TMZ’s attempt to hurt me whiffed. I sat in my car, looked at it, and immediately tweeted out what I tweeted.

It was raw, it was genuine, it was straight from the gut. Is someone really going to give me shit for doing what’s right for my child? I gave up everything for my son and I’d give it all up again. I’ll do this as long as I have to, and if I can’t do this, I’ll dig ditches. It’s my son. I didn’t get my father for very long, so I take this very seriously.

Can you walk me through your timeline of deciding to drive for Uber?

That started roughly two years ago, around St. Patrick’s Day. Literally two weeks after the American Idol finale in 2016, I took my three-year-old and fled my living situation, moving away from my then-wife. There’s no doubt in my mind I did the right thing. I got emergency custody from a judge, which was upheld by another judge for five more months. I went back to my hometown, [Ellicottville, New York], and there was a big ski resort there with a pool and a golf course called Holiday Valley. I was the keynote speaker for their orientation at one point. I had to pull my kid out of preschool when we went to [Ellicottville], but there was also a preschool at the resort. I went to the head of the place and said, “Listen, this is what’s going on. Can you give me a job so I can keep my kid in this preschool?” They hired me as a cart boy on the golf course. Me and six or seven high school and college kids. That’s what I did for the whole summer.

My wife and I eventually tried reconciling, and it didn’t work. I moved to Glendale and went on unemployment. l had my son half of the week, and the other half of the week, I sat in my one-bedroom in my underwear and I mourned. I mourned the loss of my family, everything I had been through, and then I had to figure out what to do. I collected unemployment for about six months, wanted to work in television, but that wasn’t an option without representatives—my manager and agent had dropped me after I took my son and went to Ellicottville. I decided, well, I’m not going to wait tables and I’m not going to bartend and get recognized all the time doing that. So I got rid of my BMW convertible, got a Prius, and started Uber driving. I thought, I hope this fucking works. It did. It saved my ass.

Some of the profiles and interviews I’ve seen you do over the years have ended with a question about closure, whether you’re at peace. And unsurprisingly, your answers have changed over the years. I wonder if you’ve ruminated on that before.

Yeah, you go through phases. I’m happier now than I was back then. I’m not depressed anymore—I used to struggle with depression a lot. I had a lot of anger. I feel like I’m a different person, especially what I’ve gone through in the last five years. I just feel like I’ve come out on the other side. American Idol is something that I’ll always be proud of, because I beat out a lot of people for that. I was a part of history. I have a completely new appreciation for everything. That’s the difference: I live in gratitude now. I don’t live in resentment.

And I want to reiterate, I’m grateful for the opportunity to be on American Idol. I don’t mean to come off ungrateful. It was a huge opportunity. It didn’t work out for me, it threw a huge wrench in my life for a decade or two, but here I am working for one of my old bosses from Idol again with Family Feud, and I just want to give 100 percent to every opportunity that’s given to me. Most people don’t get to do this at all, and I’m getting another chance.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How Dateline correspondent Keith Morrison became—and stayed—the granddaddy of true crime.

You can still channel surf in the streaming age and have a great time if you just believe in yourself.

Originally Appeared on GQ