Is Fonio Better Than Quinoa? Here's Why It's Time to Try This West African Grain

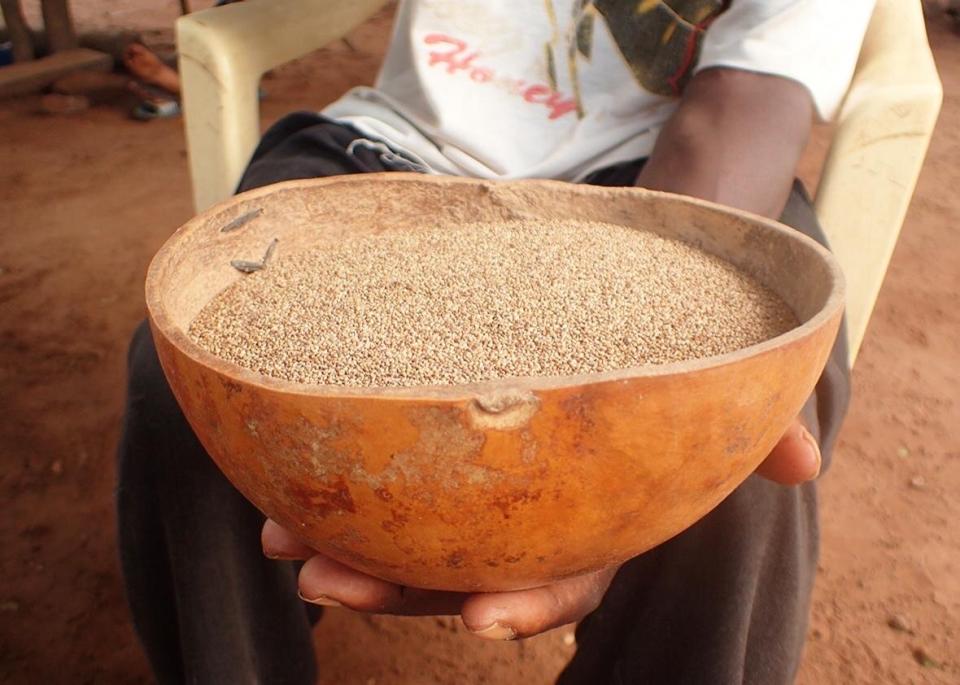

Picture the perfect grain: To us, it would cook quickly, be packed with nutrients, could be used in a variety of different recipes, taste delicious, and be grown sustainably. No, we're not talking about quinoa (which is actually a seed, not a grain!). We're all about fonio. In parts of West Africa, fonio is a staple and is even referred to as "the seed of the universe" in Mali. It's an ancient cultivated type of millet and has only recently become more widely available in the U.S.

Fonio seems poised for success. It was featured as one of Future 50 Foods for Healthier People and a Healthier Planet, in a report from Knorr and the World Wildlife Federation in 2019, and fits into the "flavors of West Africa" trend identified by Whole Foods for 2020. Another reason fonio is on the rise? The efforts of chef and cookbook author Pierre Thiam. Born and raised in Dakar, Senegal, Thiam has brought West African cuisine to the world thanks to his restaurants and his cookbooks including his most recent one, The Fonio Cookbook ($24.95, amazon.com), and his African food company Yolélé.

Related: Our Favorite Recipes for Whole Grains

The Oldest African Superfood

Thiam partnered with Philip Teverow to found Yolélé, an African food company with the mission to create a global market for underutilized crops like fonio and others from Africa, contributing to preserving biodiversity, diversifying the global diet, and, most importantly, bringing economic opportunities to small farming communities in Africa. Says Thiam, "As a chef, I always wanted to represent the food of West Africa in my cooking through my restaurants and cookbooks. While writing cookbooks, I realized that I often had to think of a substitute for certain ingredients because they were not accessible to my audience. I saw this as an opportunity to create a market for those underutilized crops." He goes on to add, "Fonio, in particular, caught my attention. It's the oldest cultivated grain in Africa, it's been around for 5,000 years. It's quite resilient and can grow in poor soil. Furthermore, it is drought-resistant and thanks to its deep roots, it regenerates the soil by adding nutrients to it. It is gluten-free and it is also very nutritious." Yolélé currently offers fonio in grain (From $5.95, amazon.com) and flour ($13, yolele,com), as well as in flavored pilafs (From $5.99, target.com) and chips ($3.99, thrivemarket.com).

From the perspective of a home cook, fonio is a dream come true; "Fonio is very versatile and it cooks in five minutes," says Thiam. "There is a Bambara language saying that 'fonio never embarrasses the cook.' Indeed, it can be turned into flour, cooked as a fluffy couscous to be used in salads or pilafs, or simply as a side, or, by adding more broth, cooked into a porridge." It's light and fluffy when steamed, and has a mild nutty flavor.

Courtesy of Yolèlè / Evan Sung

How to Cook Fonio

You can usually substitute fonio for any grain in recipes. According to Thiam, the simplest way to cook it is by combining one cup of dry fonio in one-and-a-half cups of boiling water. Reduce the heat to its lowest setting and keep the pot closed with a tight lid until the water evaporates (three to five minutes). Then simply fluff it with a fork and proceed with your recipe. He also notes that fonio is a generous grain; a single cup of dry grains can yield four to five cups when cooked.

Health Benefits

Fonio is low on the glycemic index meaning it won't cause large increases in blood sugar levels and it's high in methionine and cysteine, amino acids essential for human growth that are missing in most other grains including corn, wheat, and rice. It's also low in fat, a good source of B vitamins, including thiamine, riboflavin, and niacin, and also provides some iron, copper, zinc, and magnesium. A complex carbohydrate, it's significantly lower in calories (140 calories per cup) than rice, pasta, or quinoa.

Sustainability

Thiam is making sure that demand grows with the supply in order to avoid the "boom and bust" that happened to quinoa. "One of the ways we aim to prevent that boom and bust is by partnering with a local operator to build a mill that will process fonio in a more efficient way," he says. "Currently, fonio processing is still partly manual and suffers a high amount of waste (close to 50 percent). The new mill will remove this processing bottleneck, and almost double the fonio's availability by simply eliminating the high post-harvest loss. By processing more efficiently, we will reduce the cost and the price of processed fonio. Our business model will result in a price to smallholder farmers that's attractive enough to increase planting, but not so high that it attracts speculators in industrial agriculture, which is what happened with quinoa in South America. We will also process fonio at three tons per hour as opposed to the current one ton per day."

Yolélé is also looking for ways to protect the appellation of fonio grown by small farmers of the Sahel region in West Africa, in the same vein as protected wine-making regions.