Former Pro Cyclist and Disqualified Tour de France Winner Floyd Landis Is Now a CBD Mogul

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Floyd Landis is up to his eyebrows in cannabis. Actually, higher than that: Most of the plants in this one-acre patch, rich and lushly green, stand a good foot or two taller than the former pro cyclist and disqualified Tour de France winner.

On this warm Thursday in mid-September, Floyd and two colleagues are making the rounds of Amish farms in southern Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, checking on their crops. The plants are the same species—Cannabis sativa—that produces the marijuana that people smoke to get high, only they are technically hemp, special strains bred for low THC content (the chemical responsible for the “high”) and high concentrations of CBD or cannabidiol, the substance used in the creams, edible gummies, and tinctures sold by Floyd’s of Leadville.

Six months ago, Floyd’s placed a small advertisement in Lancaster Farming magazine, hoping to gauge interest among local farmers in growing hemp, which had been newly legalized in the 2018 farm bill. They rented a meeting room for 150 people. Nearly twice that many farmers showed up. Most were Amish, intrigued by the idea of a new cash crop to replace tobacco, their old standby, which has been in decline for years. More than 50 farmers signed on to grow test patches for Floyd’s, which provided the seeds and some initial direction. Now, several months later, harvest time is looming.

“Check these guys out,” Floyd says, holding a conical flower covered in droplets of sticky oil. “Epic,” says Wayne Bendistis, the 27-year-old head of agricultural sciences for Floyd’s. The different strains of hemp even have stoner-esque names, like Purple Haze and Sour Space Candy, although by law they can only contain a tiny amount of THC, 0.3 percent or less by weight. More than that, and it is considered marijuana, and is thus illegal in Pennsylvania.

“This one, with the orange pistils, is ready,” Wayne explains to farmer Ben King, who leans in for a closer look and a whiff. To my untrained nose, it smells the same as marijuana.

“This one over here, where they’re still white, is not.” Ben nods.

While Ben and Wayne both have dark beards, the similarities end there. The 30-something Ben sports a traditional Amish chin beard, straw hat, blue shirt, and suspenders. Wayne is pure hippie, with flowing chestnut hair and bare feet tanned the same color as the soil. Growing cannabis is his passion, and he is largely self-taught; let’s just say that it’s not (yet) on the curriculum at Penn State. For Ben, who grows a wide range of crops, from corn to ornamental cabbages, this acre of hemp with roughly 2,000 plants offers a potential payday of about $20,000, depending on market value. An acre of corn is worth around $570.

Ben’s interest runs deeper than just cash. Jake Sitler, 30, the company’s business director who also runs Lancaster County operations, hands him an assortment of Floyd’s of Leadville products, including a CBD tincture and a bottle of CBD gummies. Ben uses them to combat the aches and pains that come with working 16-hour days on his 100-acre farm. Holding up a hemp flower that fell on the ground, he says he plans to dry it and add it to the family’s “meadow tea,” a traditional Amish concoction made from foraged plants and herbs. After all, it’s just another weed.

[Find 52 weeks of tips and motivation, with space to fill in your mileage and favorite routes, with the Bicycling Training Journal.]

It certainly grows like one. “Six weeks ago, these plants were maybe waist high,” Ben tells me. “The soil did all the work.” The crop is mostly organic, too; he sprayed the plants once when they were young, but after that, he did not use pesticides. In place of chemicals, he brought in a colony of wasps to prey on the bugs that might otherwise eat the hemp buds. Still, one or two pests manage to survive. Wayne plucks a small green worm off a flower and holds it up. It seems, well, pretty chill.

“He’s probably full of hemp juice,” jokes Ben.

Several months earlier, in the spring of 2019, I had run into Floyd Landis at a bike race in central Pennsylvania, about 15 miles from where he grew up. Locals still recall him winning a nearby mountain-bike race, the first one he ever entered, wearing cutoff jeans because his Mennonite parents had deemed spandex bike shorts sinful. “He did a wheelie across the line,” remembers race organizer Bill Gentile.

“My dad asked why I didn’t go to church,” Floyd said. “I told him I won $500. I was rich!” His parents also warned him that if he continued with cycling, he would go to Hell. They might have been right about that, in a way. He had left Pennsylvania in his early 20s, and hadn’t been home much, especially since testing positive for testosterone after winning the 2006 Tour de France. But now he was back and he looked happy. “Hemp juice” was a big part of the reason.

As racers milled about, Floyd held court beside a sprinter van wrapped in Floyd’s of Leadville colors, which look remarkably like the rainbow stripes worn by UCI world champions in cycling—which Floyd never was. “We changed one color,” he laughed.

He had a small entourage, including Sitler, a local bike racer who was a teenager when Landis had tested positive. “I believed he was innocent,” Sitler told me later. “I didn’t know any better.”

All that appeared to have been forgiven. Landis wore a big smile as one after another, friends and acquaintances and complete strangers came up to say hello and chat. The beer cup in his hand always seemed full. His smile never faded. He laughed a lot. His partner, Alexandra Merle-Huet, was also there, chasing after their five-year-old daughter, Margaret, who is named for Floyd’s Mennonite grandmother.

This wasn’t the Floyd Landis who we had been reading about for so many years: the jut-jawed guy who had fought his doping positive with funds raised from many of these same people, claiming innocence while knowing he was guilty; the “bitter” ex-teammate who had finally blown the whistle on Lance Armstrong, seemingly wanting to take all of U.S. pro cycling down with him; the vengeful money-grubber who had sued Armstrong under the federal Whistleblower Act, a lawsuit that could have potentially earned him tens of millions of dollars.

That Floyd was angry and tortured. “Disgraced cyclist” could have been on his driver’s license. This Floyd seemed happy and fat (by pro cyclist standards, anyway). He could have been any other middle-aged suburban dad in a bike jersey—except for the part about growing acres of marijuana. People had snickered when Landis had emerged, three years ago, as the front man for a Colorado marijuana company called Floyd’s of Leadville. It was too perfect, the confessed doper now selling dope. “I’m happy to finally be involved in a legitimate industry,” he tweeted at the time, tongue firmly in cheek.

Since then, he and cofounder Dave Zabriskie, a friend and former U.S. Postal teammate, had managed to expand their business in the fast-growing CBD market. They were early movers into CBD, and now their products are found in some 5,000 retail outlets, including bike shops and convenience stores. Somehow, it had turned into a real business and the CBD side (that is, hemp juice) soon outpaced Floyd’s lucrative recreational marijuana dispensaries in Colorado and Oregon, which Floyd says bring in more than $1 million each month. While Floyd’s remains a niche player in the overall U.S. CBD market, which the Hemp Business Journal estimates (conservatively) is worth roughly $1 billion—CBD is found in cosmetics, lotions, even pet treats—their operation is growing, fueled largely by the move into convenience stores. “We are in 2,500 C-stores now,” Sitler said, “and that will probably double in three months.” Still, they are nowhere near the size of a company like Lord Jones, a high-end maker of CBD edibles and creams that was part of a $300 million acquisition last summer by Cronos, the Canadian cannabis conglomerate.

Floyd’s markets a range of products targeted at endurance athletes—including CBD gummies, tinctures, and balms—hence the Leadville connection. The company sponsored the 2019 edition of the Leadville 100 mountain-bike race, and maintains a sort of headquarters there, in a ramshackle miner’s cabin that also houses a recreational marijuana dispensary. (It doubles as a crash pad for athletes who come to train at the town’s 10,000-foot altitude.) “We’re trying to associate with something that people like, endurance sports, which is kind of what Red Bull does,” he says. “You might not ever run Leadville, but you’ll see the stuff in a convenience store and buy it.”

New on the market this year: A limited edition, CBD-infused coffee that they’re calling “Stage 17,” after the memorable day in the 2006 Tour where Floyd went on a solo breakaway to put himself back within reach of the leader’s yellow jersey. (That evening, of course, he submitted the urine sample that showed elevated levels of testosterone, which is banned, leading to his downfall.) Once a taboo subject, that infamous stage has become a joke.

Just to compound the irony, Floyd’s also sells a logo-ed yellow jersey. “It’s a good color to wear when you’re riding,” he deadpans. “It’s easy to see… but I guess it is sort of sacrilege.”

In Floyd’s world, sacrilege is a good thing, particularly when it comes to pro cycling. But cycling is the furthest thing from Floyd’s mind most days; he’s busy running a business. As we speed down narrow country roads in Sitler’s cluttered Prius, they jump on a conference call with a Midwestern convenience-store chain interested in carrying Floyd’s of Leadville products. Once an exotic niche product known mainly to cannabis aficionados, CBD became a mainstream market category almost overnight. Floyd’s of Leadville, which began selling CBD products three years ago, found itself on the leading edge of the wave.

The call is going well. Sitler is explaining their new vertically integrated “seed to store” business model that lets them charge lower prices than premium CBD brands. Their display stand includes an informational pamphlet describing what CBD is, and what it does (while not psychoactive like THC, CBD is thought to deliver many of the medical benefits of cannabis). “I tell you what, gentlemen,” says the female executive who’s leading the meeting. “I’m very excited. This looks nice.” An hour later the 90-store chain places a $250,000 order.

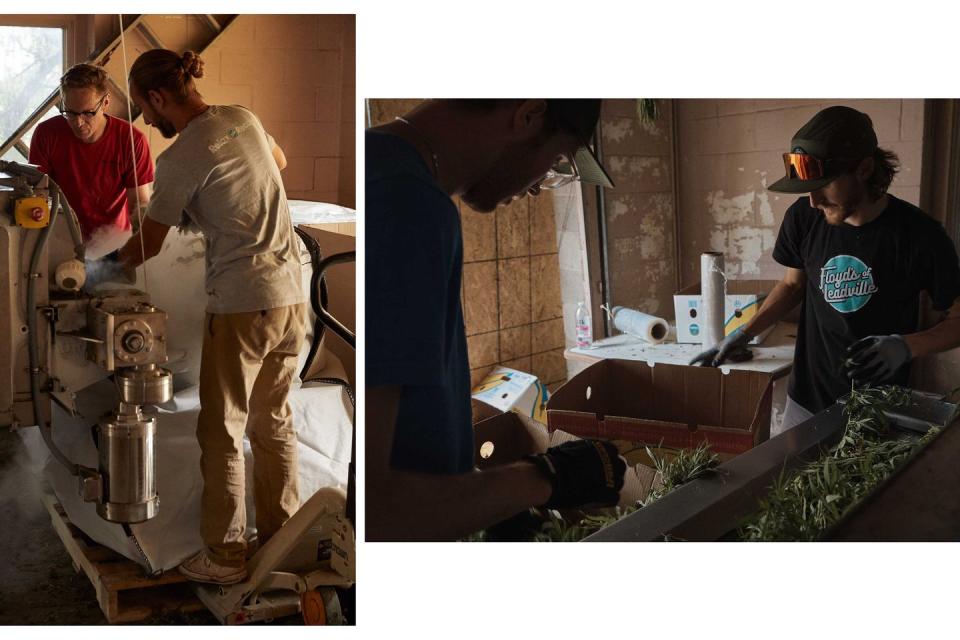

There’s no time for rejoicing. This year’s hemp crop is ready to harvest, and Floyd and his team are racing to figure out how to cut the stuff, and how to store it until it’s ready to be processed. That morning, they had been tinkering with a cryogenic freezer machine, tucked into an abandoned car wash owned by Floyd’s dad; they have only just signed the lease on a 10,000-square-foot space in a nearby town where they’ll open a processing facility to extract the CBD from the hemp plants.

Meanwhile, though, the farmers are getting antsy. “I see a lot of work in it yet,” says Ben King, scratching his head. This is the first legal hemp crop in Lancaster County in 82 years, and there are many unanswered questions. When is it ready to cut? What’s the best way to harvest the CBD-rich flowers? And most of all, will hemp be profitable enough to justify all the work? Ben plans to enlist his four brothers to cut the plants by hand, in the evenings after their main chores are done.

“Dude, the Amish are badasses,” says Floyd. He grew up Mennonite and while the two sects are sometimes confused, Mennonites avail themselves of modern technology that the Amish traditionally reject, such as automobiles, electric appliances, and bicycles with gears. Hemp plants are tough and sticky, and there is no such thing as a hemp-harvesting machine (yet). But the Amish still farm largely by hand, which is why they are perfect for growing such a labor-intensive crop.

There is further uncertainty around the future of the hemp market. This was the first year that hemp could be grown on a basically unlimited scale, under the 2018 farm bill, and farmers nationwide planted about 250,000 acres, according to Beau Whitney of the Hemp Business Journal. The roughly 65 acres sewn by farmers under contract to Floyd’s represent a tiny drop in that bucket. The company plans to use what it needs to make its products, and then sell the rest on the open market. “Until this year, there’s been more demand than supply,” says Whitney. “Now there is supply, and a lot of it.” If demand for hemp does not also rise—not just for CBD oil, but for the crop’s many other potential uses from fibers to seed to even plastic-like products—farmers like Ben could face a drop in prices.

Ben’s next-door neighbor, Daniel Miller, whose mirrored aviator shades make him resemble an Amish Bob Dylan, is already skeptical. He also has an acre of ready-to-harvest hemp plants, but is concerned about how much he stands to be paid (the farmers will be compensated based on the amount of CBD oil the flowers produce, says Wayne). “I’ll be thanking you when I get the check!” he tells Floyd, only half joking.

The money shouldn’t be a problem. Floyd’s phone rings again, and this time it is a guy from a firm specializing in mergers and acquisitions in the cannabis industry. Would he perhaps be interested in a Pennsylvania medical marijuana license, for the low price of, say, $20 million? “He’s gotta be high,” Floyd jokes after hanging up.

I venture a question: Is the cannabis business better, financially, than pro cycling?

“It’s not even close,” he laughs. “Not even close.”

You could argue that cannabis helped save Floyd’s life. After he blew the whistle on doping at U.S. Postal in 2010, he was stuck. He was out of money, divorced from his first wife, and living in a lonely cabin in the mountains of Southern California. Getting back into the bike industry was probably not going to happen. “Some days I’d get my cycling kit on and start to ride, but then after 10 minutes I’d be like, fuck this, and go home and just drink,” he says. “My bike had been my one drug, and then all of a sudden it had the opposite effect. I just couldn’t handle it.”

So he substituted other drugs. Some days, he says, he consumed all his calories in the form of beer. But booze wasn’t his biggest problem; he had begun using opioids after having his hip replaced, and it was easy to get more pills. “I had prescriptions, and all I had to say was that my hip hurts, and nobody would question it,” he says. “I’d take a pill, and I’d drink with it. It turns your brain right off. I mean, the label says, don’t use with alcohol—so you know it’s gonna work,” he laughs. “I was lucky to live.”

He desperately needed to figure out the next act in his life. Out of money, he moved to Connecticut, where he stayed with a friend named Tiger Williams, an avid cyclist who works in the hedge-fund business. Williams invited him to join his firm as a trader. That lasted two days. Williams then suggested he try to get back involved with cycling somehow, perhaps as a coach. That had zero appeal, and besides, Floyd laughs, “I’m the worst coach on Earth.”

WATCH: FLOYD LANDIS ON CBD BENEFITS FOR CYCLISTS

He needed to get out of cycling altogether. He eventually bounced to Colorado in 2013, where he worked for a time in a compounding pharmacy, but that ended when it got shut down by the FDA. Marijuana had been legalized in Colorado in 2012, so Floyd and some friends set up a growing and processing facility in the Denver suburb of Aurora. That seemed like a good fit; he certainly enjoyed the product. More than that, smoking marijuana—which he says he had never done until well after he retired from cycling—had helped him break his addiction to painkillers and booze. It calmed his anxiety, he says, making it a softer substitute for the pills.

He never thought it would turn into a business, and he never thought he would end up as its figurehead. But it’s illegal to advertise cannabis—and that led to putting the name of the group’s most publicly notorious partner front and center. In April 2016, the enterprise became “Floyd’s of Leadville.”

The irony was too good for the press to resist. “Floyd Landis is rolling with the dope crowd,” punned the New York Daily News. Floyd’s Leadville dispensary became a cannabis destination, enabling the company to purchase four more dispensaries in Portland, Oregon, as well as a 45-acre marijuana farm in that state. Initially, Floyd’s sold only THC products, but when one marijuana crop failed to yield the high levels of THC that were expected, one of Landis’s partners saw an opportunity. They processed the plants to produce a batch of CBD extract and put that into some new products, including gummies. That was the beginning of Floyd’s CBD business. Because CBD is not considered a controlled substance by the federal government, they could expand beyond Oregon and Colorado—and they could sell it online to the many potential customers who visited the Floyd’s of Leadville website.

At the time, CBD was just gaining traction for its purported anti-inflammatory and anti-anxiety powers, so it seemed logical for Floyd’s to target the athletic market. Landis and Zabriskie, who had become a partner in the company, toured hundreds of local bike shops trying to get them interested in the CBD products. They drew little interest at first, in part because of uncertainty about CBD’s legal status; even now, Floyd’s keeps a law firm on retainer just to map the ever-shifting matrix of federal and state regulations pertaining to marijuana and CBD.

They got a break when they managed to get their products listed in the Quality Bike Parts catalog, where most bike shops order their supplies. Sales took off, to the point where Floyd’s of Leadville’s CBD business more than equaled the marijuana side (which is a separate legal entity now known as Floyd’s Fine Cannabis). The economics of CBD are attractive: The active ingredient in a 50mg CBD gummy costs about 15 cents, while the final product sells for $2.99.

“Our marijuana business does well, but I actually like the CBD side of it better, because I’m not a huge fan of being high all the time,” Floyd says. “It’s fun once in a while. But I don’t get a lot done when I’m high.” (He does allow that THC makes the experience of flying commercially, which he does often, more tolerable.)

Also, because marijuana remains federally illegal, it’s difficult (and expensive) to bank the enormous amounts of cash it generates. Congress recently clarified banking laws to make it easier to handle marijuana revenues, but under federal tax law, cannabis is still considered a “criminal enterprise” and is thus taxed on gross revenues rather than net profits (translation: much higher effective tax rates).

While CBD from hemp is now federally legal, it remains in something of a regulatory limbo. The FDA has approved a CBD-based prescription drug, Epidiolex, to treat two rare forms of epilepsy, but it has yet to decide whether to consider over-the-counter CBD a drug or a dietary supplement. The agency website is full of warning letters to CBD companies, taking issue with various wild health claims made on behalf of CBD compounds; so far, they seem to be OK with Floyd’s of Leadville’s vague-enough slogan, “Relax and Recover.” But it remains unclear as to how the agency plans to treat CBD in the long run.

Meanwhile, the horse is exiting the barn at high speed. Floyd’s of Leadville’s CBD business was growing so quickly that in September 2018, Floyd’s partner Alex quit her job as a vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York to help run the company. Floyd’s of Leadville now has 30 employees spread across five states. The marijuana side of the business, which is a separate legal entity, still has five dispensaries and two farms in Colorado and Oregon (although Floyd says he wouldn’t mind getting rid of the Oregon operations to cut down on travel time). Alex handles the operations side, leaving Floyd free to be Floyd. When he’s not wrangling hemp in Amish fields, he is the public face of the company, popping up with Zabriskie at events like Leadville and Levi’s Gran Fondo, and doing interviews with everyone from the Wall Street Journal to a Pennsylvania-based cycling podcast called “The Gretna Bill Show.”

“Floyd and I are very good together,” Alex says by phone from their home in Larchmont, New York. “He’s a very creative ideas person, a visionary, so he’s a good CEO. I help him execute and run the day-to-day logistics.”

When they met at a holiday party near New York City six years ago, she had no idea who he was. “Alex is good for him,” says their friend Dave Towle, the bike-race announcer. “She is the one person who can stop him from making decisions based on his old instincts.” She also keeps him focused on the future, rather than dwelling on the past.

Floyd and Towle had been adversaries on Twitter and in person after Landis confessed and spilled the beans on Lance and his U.S. Postal teammates. Like many who made their living in American pro cycling, Towle had criticized Floyd harshly. “My heart knew one thing, but I had to operate in a world of getting paid,” he says now. A chance meeting led to an email, which led to Towle ultimately “apologizing for being such an asshole.” When Towle was diagnosed with pancreatitis a couple of years ago, Landis invited him to stay at Floyd’s Leadville headquarters for as long as he needed to.

Floyd’s of Leadville’s expansion into Lancaster County is important business-wise, but also personally; he’s coming home. After Floyd, Jake, and Wayne finish making the rounds of farms, we drive back into the city of Lancaster, to an unfinished storefront wedged between a burrito joint and an adult bookstore. Inside, construction is halfway done on what will eventually become “Floyd’s of Lancaster,” a combination coffee shop, bike shop, and CBD outlet. It is not inconceivable that Pennsylvania could legalize recreational marijuana, having already permitted medical cannabis three years ago. If that happens, this space in ever-more-hipster downtown Lancaster would be an ideal location for a marijuana dispensary. And there will be plenty of local farmers who already know how to cultivate cannabis plants.

For now, they are playing a waiting game. Meanwhile, CBD has been a vehicle for other kinds of healing. It’s given Floyd a purpose, made him some money, and brought him back to his roots, a place he avoided for years. His father Paul was a small businessman and sometime auctioneer; his mother, Arlene, still works a few days a week at the Shady Maple Smorgasbord, a local institution. “There were a lot of years where I really didn’t talk to my parents very much,” Floyd says. “And now I see them every week or so. I’m happy about it. They’re in their 70s now and they’re not going to be around forever.”

“He’s finding his groove,” says Towle. “He’s like a record player needle that kept skipping along on top of the record. Now it’s finally gotten into the song.”

The last obstacle to Floyd escaping his past was partly self-imposed: The whistleblower lawsuit he had filed against Armstrong and other officials of the U.S. Postal Service cycling team back in 2010. The government had joined on Landis’s side, and the case dragged on for eight years before it was settled in April of 2018. The settlement required Armstrong to pay Landis about $1 million, plus his attorney’s fees.

It was a bit anticlimactic, given that Landis could potentially have won millions by some reports. But he flipped the script by announcing that he was putting his share of the settlement (about $600,000) into a domestic road racing team, of all things. In one move, he inserted his name back into pro cycling, while making an elegant statement: Thanks, but it’s not really about the money. (A separate fund was established to repay donors to the “Floyd Fairness Fund,” which he had set up to pay for his own doping defense.)

Floyd’s Pro Cycling got off to a pretty good start this season, winning enough stages to be ranked the world’s top Continental team, but it was left off the initial roster for the Tour of Utah, despite the fact that three of its riders had placed in the top 10 overall in previous years, and sprinter Travis McCabe had won four stages. According to Landis, the team was told that the race’s main sponsor, the strongly Mormon Larry H. Miller family (they own primarily auto dealerships, but also the NBA’s Utah Jazz), had “moral issues” with Floyd’s name. The problem was solved by renaming the team after another sponsor, Worthy Brewing of Portland, Oregon. Floyd took it personally, which raised the question: Why sponsor a pro cycling team at all?

“I still miss it,” he told me last summer. “Look, I like it. Those were some of the most educational and enjoyable times of my life. I got to see the world because of it. So I don’t resent cycling at all, as much as I just kind of laugh at it all. I just wish it was managed better.”

Last summer, he was on the fence to whether he would continue to sponsor the team next year; it might make more sense, he said at the time, to focus on the mass-participation events like Leadville and Dirty Kanza that appeal more to Floyd's core customer. And in November, Floyd’s Pro Cycling announced that it was folding. His third foray into pro cycling was over.

Floyd was in Utah for most of the Tour of Utah race week, in August, but barely showed his face at the actual race. He was too busy with business matters; Utah is a major hub for the supplement industry, and he and his team were in nonstop meetings all week. I tagged along for one of those meetings, which took place on a mountain-bike ride. On a Friday morning, I met Floyd and Dave Zabriskie at a trailhead near Park City. Waiting for them in the parking lot was Cameron Banko, a local entrepreneur who owns a CBD company, to talk about upgrading Floyd’s of Leadville’s topical products and packaging.

Zabriskie had been a reluctant business partner, at first. When he was growing up in nearby Salt Lake City, his father had made ends meet by selling marijuana and had run afoul of the law while Dave was in junior high. Zabriskie says he became a convert after using CBD products to treat lingering pain from the injuries he suffered during his cycling career.

Landis and Zabriskie had been thrown together on U.S. Postal in 2002, and they became roommates and close friends. Lance dubbed the pair “Dumb and Dumber,” but neither is particularly dumb. Zabriskie is reserved, taciturn, with an offbeat sense of humor that unnerved Lance; Landis is outspoken and questioning, which chafed the boss in a different way. They both began doping while on Postal and saw their careers flourish during and immediately after Lance’s reign. Floyd won the Tour, obviously, while Zabriskie became the first American to win a stage in all three Grand Tours. The pair appeared on the cover of Bicycling before Landis’s positive test turned cycling upside down. “That all seems like a movie to me now,” Floyd says. “It doesn’t seem real.”

The marijuana/CBD business provides more than enough diversion to keep them from dwelling on the past. “Some athletes have a really hard time finding anything to do after they quit,” Floyd tells me later, as we drive back to Salt Lake City. “Because the way you get treated when you’re a professional athlete, you end up living in Bizarro World. And the people that say they like you, they want to help you, and want to be around you all the time—when that’s over, they are nowhere to be seen.”

That is especially true if you go from the pinnacle of the sport to doping-positive pariah within the space of two weeks, then you confess all, implicating many of your former colleagues and competitors. Floyd’s doping revelations had helped hasten the end of his friend’s cycling career. When Landis eventually spoke out, in 2010, Zabriskie was among the first to testify in support. The U.S. Anti-Doping Agency suspended him for six months starting in September 2012, and the 2013 season would be his last as a professional rider.

The cannabis business brought them together again. For two former athletes, it seems like not a bad way to spend one’s “retirement.” It is fast-growing, fast-moving, and the rules are being made up along the way—not unlike a bicycle race. Cycling, Landis says, was the perfect training ground for his current job, with its many uncertainties and intense competition. “It’s like in cycling, there are decisions you have to take on the fly, and they make the difference if you win or lose,” he says. “It’s kind of the same here. It’s always changing and you have to gamble. It’s fun, because everyone is trying to figure out what’s gonna happen next. We’re just kind of making it up as we go along.”

“Floyd always compares it to a bicycle race,” says Alex, later. “He’ll say, don’t worry about how many other riders there are, just focus on our team, and what we are doing.”

As we head up the trail, which begins with a long, rocky climb, Zabriskie rides ahead, while Floyd is content to hang back with Banko and me. “I like your pace more,” he says. At the time, Zabriskie still shaved his legs, and while Floyd carries a good 25 more pounds than he did as a racer, he’s still got the engine he was born with.

After a mile or so, he can’t take it anymore. “That asshole still rides way too much,” he says, standing up on the pedals and disappearing around a bend.

You Might Also Like