After the flood, organization teaches how to save personal treasures, artwork

People are hoarders of personal histories. Photographs on the walls, hand-written recipes, birthday cards, signed books or posters are all irreplaceable artifacts that tell generations of family stories and build collective histories of our communities. Recent storms in Vermont inundated houses, businesses, libraries, and art studios threatening the legacy of these histories.

Vermont Arts & Culture Disaster and Resilience Network (VACDaRN) has been preparing for a disaster, much like the one July saw, since its founding in 2019. Following the floods, VACDaRN has been teaching individuals to save their own water-logged possessions, offering demonstrations developed by the Smithsonian to the public, entitled “Save Your Family Treasures.”

The demonstrations, typically delivered by FEMA’s Heritage Emergency National Task Force, have been delivered by Katelynn Averyt, a disaster response coordinator with the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative and member of VACDaRN steering committee. VACDaRN began offering demos using their resources because they were able to reach the public immediately after the floods.

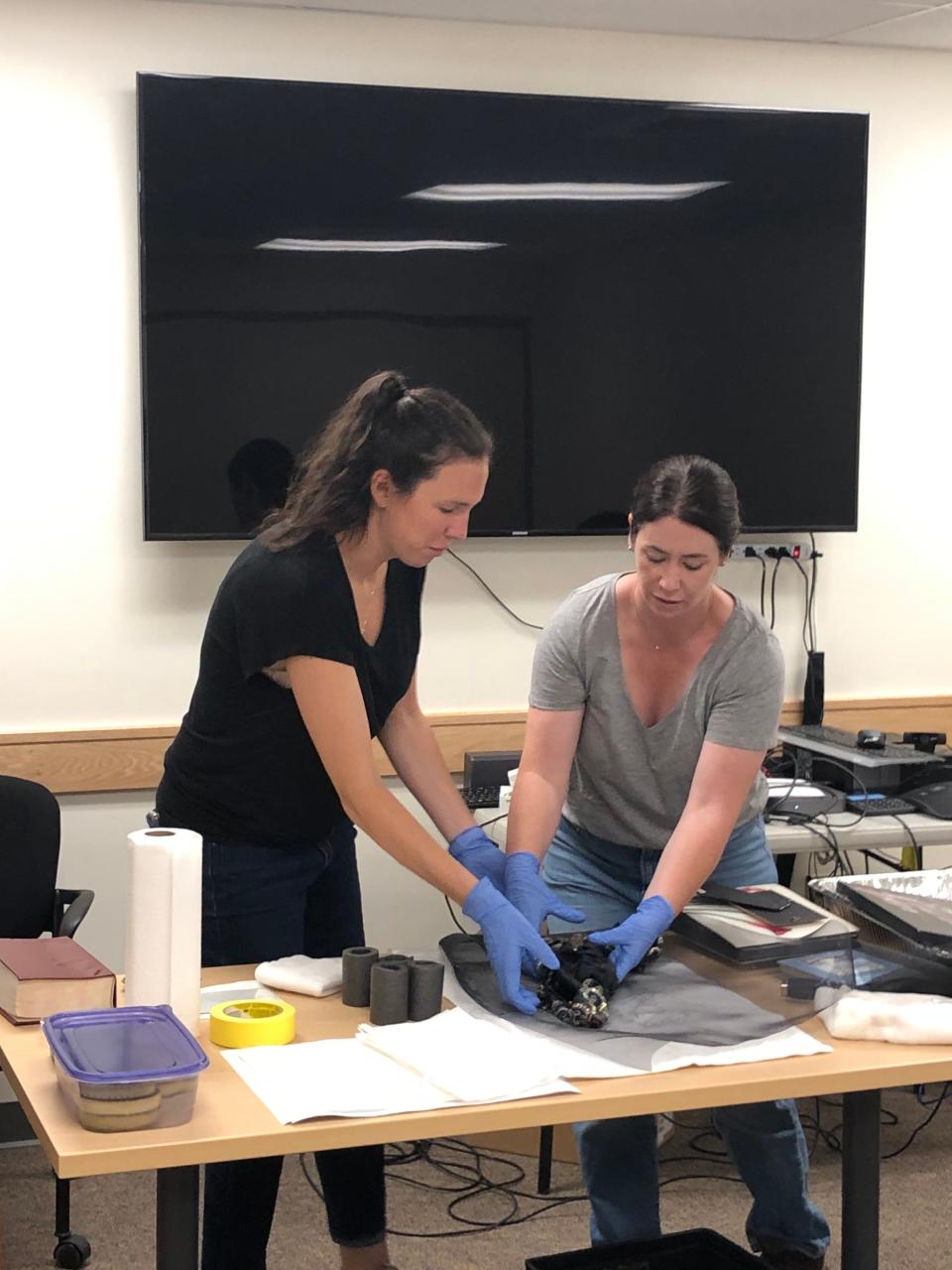

Averyt, with the help of other conservators, teaches people how to salvage papers, books, photographs, textiles, and wooden furniture– multiple formats treasures might come in– from water damage.

“We often have the impulse if something gets wet, we just throw it out,” Rachel Onuf, director of Vermont Historical Records program and founder of VACDaRN, said. “Just because something is wet doesn’t mean it’s destroyed. Things can be dried out and they can be cleaned.”

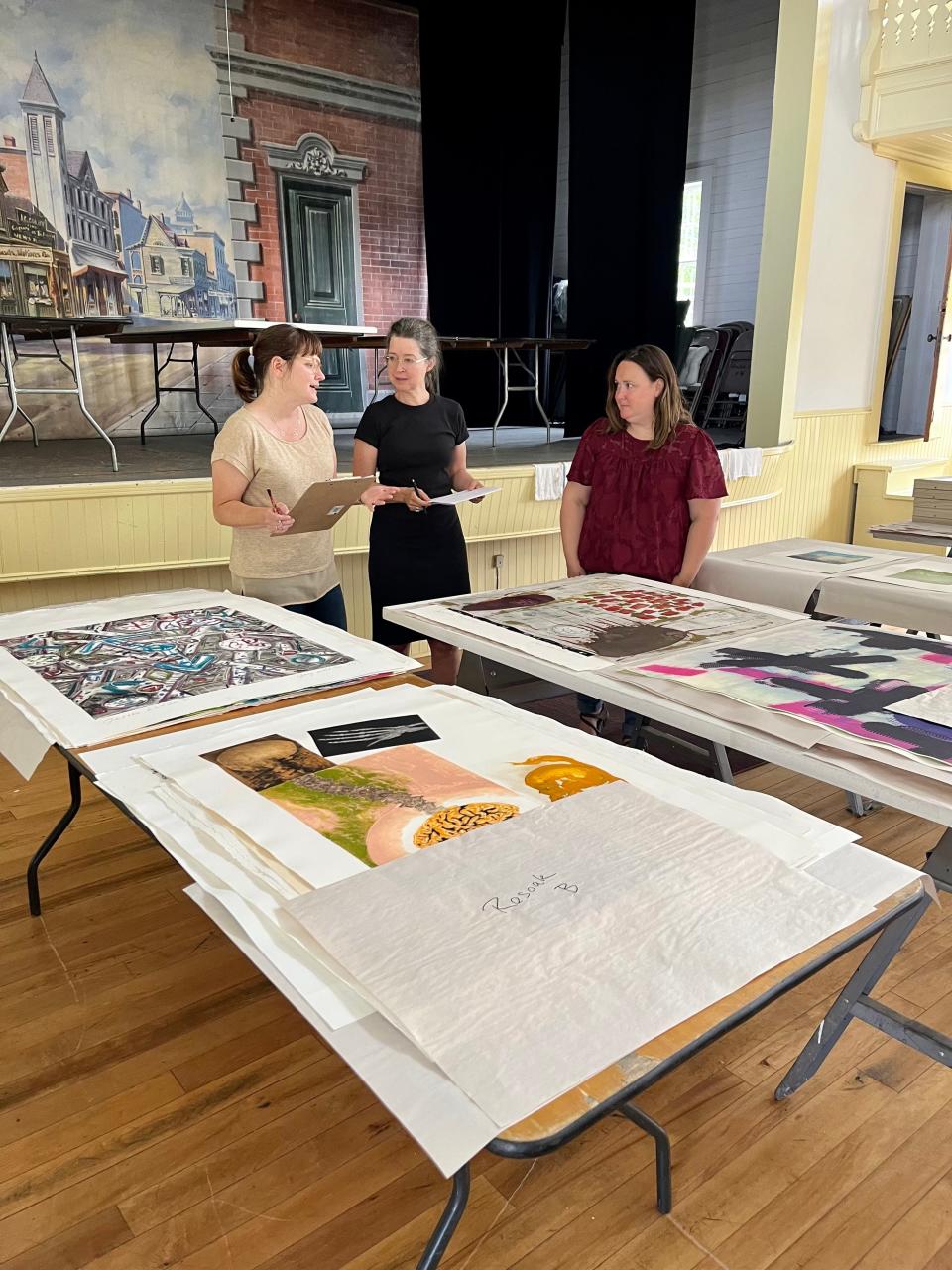

Carolyn Frisa, paper conservator with her private practice Works on Paper and advisory board member for VACDaRN (to name just two of multiple titles in her conservator work) is also leading a workshop for Vermont Studio Center artists and volunteers for salvaging their print collection– a quarter of which was lost during the floods. Teaching community members to do this work themselves is another part of emergency preparedness.

How VACDaRN saves water-logged materials

More: Rain threatens Special Collections Middlebury hit by historic storm, flooding: Community in stages of clean up

When paper gets wet, it’s essentially just getting a bath, said Onuf. Though it might be counterintuitive, if paper is damaged by contaminated flood waters, oftentimes salvaging protocol includes rinsing papers to get rid of contaminants after an initial dry out stage. Some inks run, which unfortunately cannot be reversed, but otherwise, wet paper can be saved.

In the July 10 floods, water entered 22 state buildings in Montpelier, damaging a literal truck load’s worth of public records. The truck that transported the documents to salvation was a freezer truck, which took the documents to be vacuum freeze-dried.

Wet papers can be salvaged in this way due to a process called sublimation, in which a frozen state can turn to a gaseous state without passing through a liquid state, said Onuf.

At home paper drying techniques, like what demonstrations covered, include natural indoor drying processes that avoid heat-based drying, according to FEMA’s website. The Heritage Emergency National Task Force suggests using gentle air-drying by increasing indoor airflow with fans and dehumidifiers.

When it comes to wood, Onuf advises drying it out slowly, “otherwise you can cause cracks and other mechanical damage.”

It’s safe to say that anything damaged by flood waters needs to be cleaned. When water gets into porous materials, gasoline, chemicals, sewage – anything that might be in flood waters – is also deposited into the material. Unfortunately many wood fixtures in downtown Montpelier were thrown out because the water was so contaminated.

Demonstrations covered cleaning processes as well, which might include carefully rinsing out possessions – yes, paper as well – with distilled water. While demonstrations are no longer happening through VACDaRN, Heritage Emergency National Task Force and other federal partners will be co-leading demonstrations at FEMA centers and potentially state and county fairs.

“If it’s a piece that you really care about and it’s been impacted with contaminated waters, reach out to VACDaRN and we can set you up with a furniture conservator,” Onuf said.

Storage is a preventative key in saving family treaures

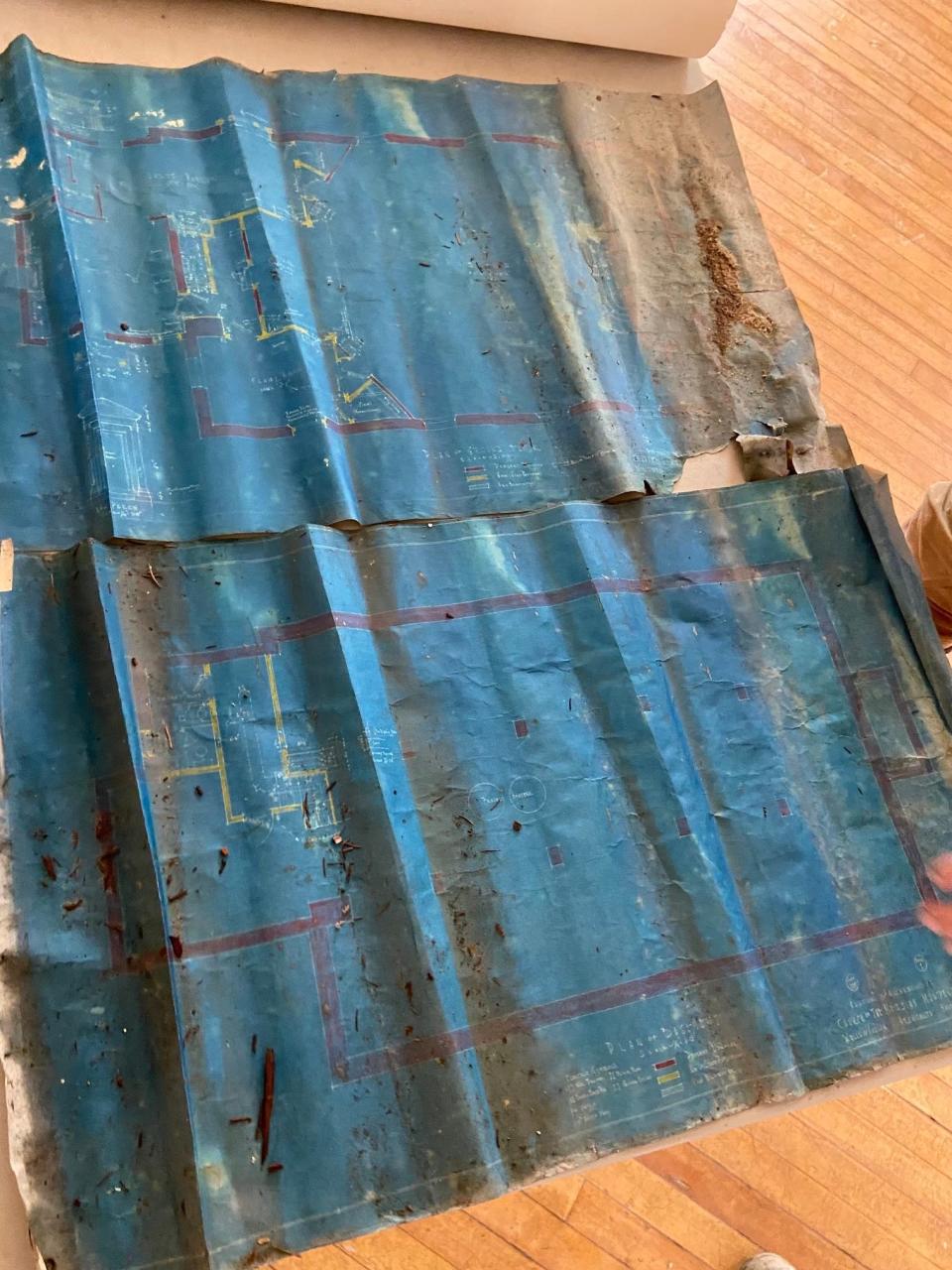

Frisa is currently working on restoring 1928 blueprints of the Unitarian Church of Montpelier, found tucked under a church stage during clean-out.

Just as these blueprints are going from ruined to new-found artifact in the wake of floods, taking this post-flood clean-up and reckoning phase as an opportunity to take inventory of your treasures is a great idea, according to Frisa.

Properly storing irreplaceables is essential to both mitigating losses in the event of disaster and minimizing general degradation over time; it is the most essential preventative step to take in ensuring treasures stay safe.

Tips for storing paper and photos

“Do not store things you care about in basements or attics,” Onuf, said.

If you take one thing from this article, let it be this.

Frisa echoed this statement, explaining that it’s not only relevant to flood scenarios – especially when it comes to paper.

“Store them in an environment that is most comfortable to you as a person, avoiding high humidity levels, which is why basements even if non flooding times are not ideal,” Frisa said.

A good storage environment should ideally be below 50% relative humidity and should stay relatively cool, at 72 degrees or lower – hence no attic either. Papers should not have contact with direct sunlight, as sunlight can fade inks and darken paper. For framed pictures, make sure you use UV filtered glass or plexiglass.

Frisa suggests storing photographs and papers in storage sleeves inside of an acid free container. Paper absorbs acid from surrounding materials; highly acidic corrugated cardboard is often a destructive culprit that stains papers with vertical lines.

Polypropylene film sleeves or polyester sleeves are ideal for storage. Sleeves, as well as tips for storing family photos and more can be found on Gaylord Archival’s website– a company that supplies preservation professionals.

Teaching artists to save their work

More: VT arts scene post floods After the flood, Vermont arts organizations present events while picking up the pieces

The DIY sentiment of VACDaRN’s “Save Your Family Treasures” demonstrations stem from the enormity of disaster and extends to saving professional art.

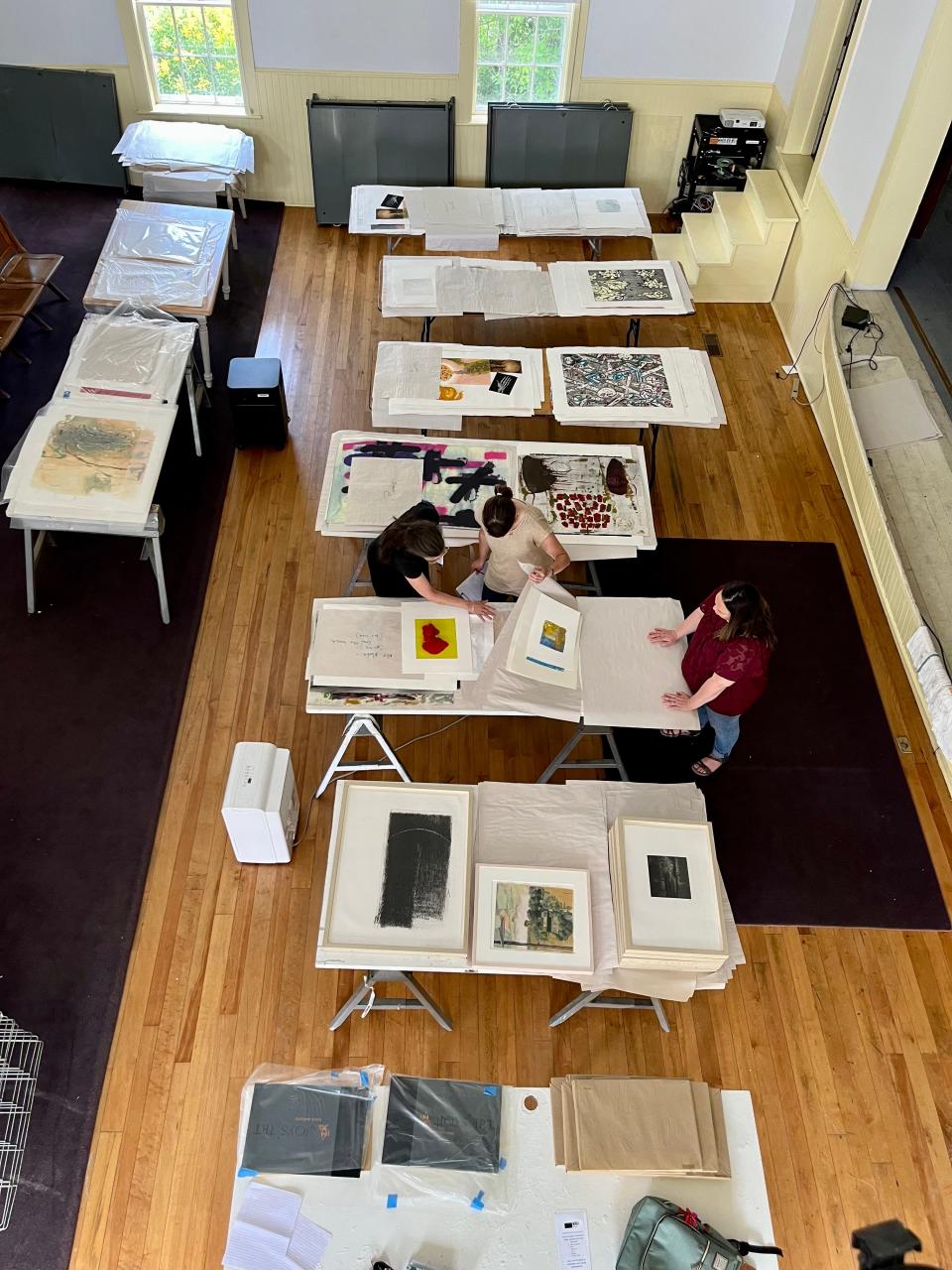

Vermont Studio Center, an international artist and writers’ residency program in Johnson lost a quarter of its vast print collection, compiled over decades by master printers.

“VSC’s Print collection is comprised of prints made over decades by master printers and represents years of artmaking and creative exchange at VCS,” a VSC Instagram post reads.

Conservator MJ Davis and Sarah Amos completed an initial assessment to oversee the drying process and figure out a plan to save around 362 prints. Frisa and colleagues are proceeding to train artists and VSC volunteers on how to clean the prints.

With such a vast collection in need of help, the scenario means all hands on deck, empowering people to learn these conservation practices for themselves. Frisa will complete more complex treatments on complex artwork and highly damaged prints at her studio.

VACDaRN background

A partnership between the Vermont Arts Council, Vermont State Archives and Records Administration, and the Vermont Emergency Management Association, VACDaRn is the brainchild of Onuf who saw a need for emergency preparedness in cultural heritage organizations.

“Many of us now recognize that extreme weather events are the reality and this is going to keep happening,” Onuf said.

Residual momentum following tropical storm Irene helped develop emergency preparedness and response networks for the arts, history and archives, said Onuf.

Frisa says having this network already in place was essential to efficient and effective disaster response following the floods, especially when it came down to directly providing help to the public.

“I was here for Irene, and our response as a group of preservation professionals has been so much more organized and effective because of VACDaRN and having that network already in place.” Frisa said.

Frisa began participating in disaster response training through the National Heritage Responders as part of the American Institute of Conservation, started by Vermont based paper conservator MJ Davis. National Heritage Responders, where Frisa is a conservator member, essentially accomplishes what VACDaRN does, but on a national level.

Contact Kate Sadoff at ksadoff@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Burlington Free Press: Conservators help save flood-damaged family treasures