Five Women Get Real About Complicated Mother Daughter Relationships

What makes the relationship between mother and daughter so fraught, so ferociously loving, so freighted with meaning-whether you speak daily, or she's been dead 20 years? Five women weigh in on the wonders of this singular bond.

The Long and Binding Road

It was hard for Jacquelyn Mitchard’s adopted daughter to accept her new home. And even harder to accept the woman offering it.

I remember exactly where I was when I first saw her face. On a cold fall afternoon, I was sitting on my bed with my laptop, revising a novel, when an email arrived. A friend had sent me a photo of four little girls, all Ethiopian orphans; she hoped to adopt two of them. But it was one of the others, the oldest, who drew my eye. She was the most beautiful human being I’d ever seen.

She would likely never be adopted, my friend told me. She would likely be forced to support her little sister-the fourth girl in the photo-by working as a prostitute. She would likely contract AIDS and be dead before age 20. Her dad had died of AIDS, and when her birth mother saw no alternative but to surrender her children for adoption, this girl had threatened to drink bleach. She would never leave her mother, she said. She would never go to America.

I tried to put the girl out of my mind, dragging the photo to my computer’s trash can, then emptying it. But I could not forget her face. One day, on what I convinced myself was a mere whim, I called the adoption agency. Had anyone adopted the other two girls in the photo? No, I was told. The big sister was the problem: She was...difficult. I asked, did she have special needs? No, the social worker said. She was just fierce.

My husband and I had enough children–seven, to be exact, some biological, some adopted. They ranged in age from Rob, 23, to Atticus, just 3. We’d also recently had a financial catastrophe-hardly a good time to take on more responsibility. Yet I felt such longing for this fierce child. And so, ten months later, on Christmas Day, Merit and her little sister Marta came home to me.

At first things seemed fine: Merit was fascinated by snow; she loved her Christmas presents. I was optimistic. I knew cross-cultural adoptions could be complicated, even seen by some as wrong. But I’d done this before. What could be so different? This: Merit hated me.

In the days after her arrival, she grieved with an intensity I had never before witnessed. She refused to eat anything except bread. All she wanted from me, she let me know, was an education. She told me one night, as we walked to our minivan in a parking lot, that she would never be an American citizen, ever. “Honey,” I told her, “you already are.” Merit turned and kicked the side of the van, denting it. The other kids gasped. “I am not your honey,” she said.

And she was not. At times, I could draw Merit to me. When I cooked, I would measure the ingredients, and, unobserved, she would put them into the pot. She let me take her out to skate on the frozen lake, where she was absolutely unequipped and absolutely fearless. She laced up her skates and fell 40 times. We went together for swimming lessons, and at the pool she climbed the ladder to the highest diving board and jumped into the deep end, straight down to the bottom, where she stayed until I hauled her up. She clung to me until we reached the edge, then pulled herself out, refusing my help, and walked away.

When I read Little Women aloud for the other children, she would listen outside the door. I even took her to Orchard House in Concord, Massachusetts, and showed her the room where Louisa May Alcott wrote. I saw tears in her eyes when I told her the classic was based on the author and her own three sisters. But Merit denied how moved she was.“It’s not real,” she said. “It’s a story.”

On her first birthday in the United States, when she turned 11, we played a game, a family tradition. Each of us expressed a wish for Merit, then she got to voice a wish for herself. “To move to a beautiful huge city far away from here,” she said with a smile.

Finally, I realized, all I could do was all I could do. Nothing would ever bring us closer. A year passed this way. I think the fight was about my putting butter on her peas (she hates butter), but whatever it was, on a frigid fall evening Merit refused to come inside, sitting all night on the trampoline in our backyard, drinking water from the hose, telling the other kids she didn’t care whether coyotes ate her. Eventually, I gave up on trying to lure her inside.

I woke to find Merit in the darkness next to my bed. I wondered whether she would hit me. Instead, she said, “Okay, I will take you as my mother.” She got into the bed and I held her, and she cried for three hours until she fell into a sleep that lasted a night and a day.

I have never struggled so mightily for a relationship-not with a lover, nor a husband, not with anyone. We still rarely go a month without a verbal sparring match. And yet, of all my children, Merit is the one I know without question would risk her life for me.

Not long ago, I heard her describe the house she would build when she’s grown, with five bedrooms: one for her and her husband, one for her daughter, one for her son, one for guests. That’s only four, someone said. “Well, one is for Mom,” she said. “When Mom is an old lady, she will live in my house.”

For her college essay, she wrote about my struggles to grow a lemon tree indoors. It included the lines, “I am my mother’s lemon tree. I thrive where I was not planted.”

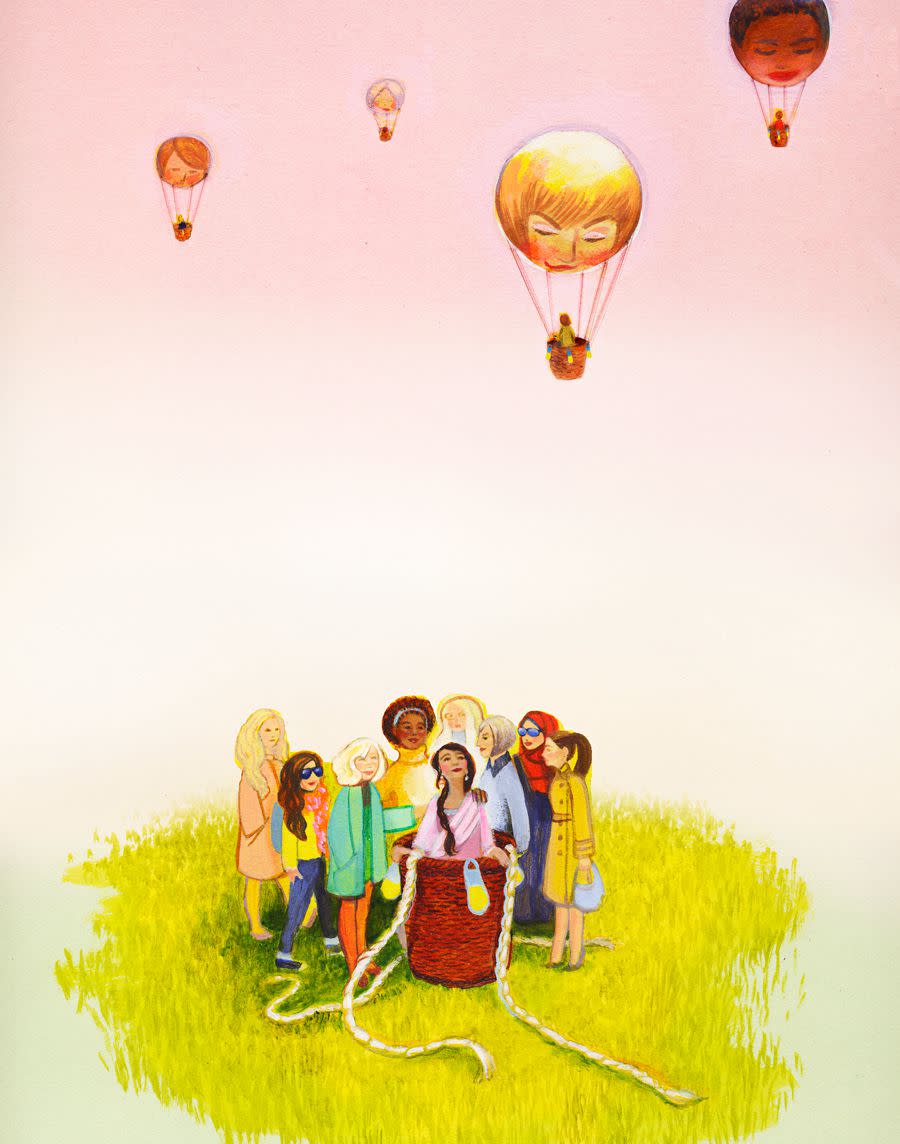

Stronger Together

Kris Crenwelge traveled to the foothills of Georgia-and the solace of 19 strangers-to grapple with a singularly devastating loss.

My mother died of cancer when she was 34 and I was 10. As a young person, I struggled to envision living past the age she was when I lost her; once I did, I had no idea what to do with myself. Part of me still felt 10 years old, waiting for guidance I would never receive. Mother’s Day was the loneliest day of the year-a reminder of what was missing. I refused to celebrate it with my kids.

For nearly 40 years after her death, I told myself I was fine. And outwardly, I was-I’d managed to become a successful, thriving adult. But the kid in me was still suffering, and she didn’t know how to make it stop. Grief-unresolved, lurking-popped up at random, inappropriate times: Over the years, I’d feel a little zing in my chest when I saw mothers and daughters shopping or having lunch. When my friends complained about their moms, I couldn’t commiserate. In fact, I often grew angry: At least you have a mother to annoy you. I was fascinated by women the age my mother would’ve been, but hesitant to befriend them-I didn’t want to appear too needy, to turn them into surrogate moms against their will. Like most people, I cry during Steel Magnolias, but when I couldn’t stop bawling at the end of Bad Moms, I knew I had some issues to address.

Chief among them was the fear that I’d lost my connection to my mother-the person, rather than my mother the sick person. When I remembered her, I always pictured her ill and feeble. But in life she had been positive and upbeat, with a loud laugh and a Texas drawl; she called everyone “honey.” To me, she looked like a combination of Elizabeth Taylor and Mary Tyler Moore: tall, with black hair, sparkly hazel eyes, and a huge fuchsia smile. She was proud of her Grecian nose and double-Ds; she was chubby and couldn’t have cared less. She was her college’s homecoming queen. She sat on the PTA. She was fearless, and people liked her, and I wanted to superimpose that version of her over the invalid who had hijacked my memory.

So a few years ago, I attended a motherless-daughters weekend retreat at a spa in Georgia’s wine country with 19 other women, all of whom had been 20 or younger when their mothers died. I was intrigued, but wary. Growing up, I had learned to not talk about my mother-doing so made people uncomfortable, I’d found. Also, I’m not great at sharing with strangers, and while I enjoy yoga (which was on the agenda), I worried I’d have to bare all in group discussions, maybe engage in sappy trust falls.

What I found instead was a sisterhood. Sitting in a circle in the yoga studio, which had a 180-degree view of the Blue Ridge Mountains, we told our stories. Each was different, but as I listened, I heard themes from my own life. We all felt the same: stuck, frozen at the age we’d been when our mothers died. We all had a fear of dying young and, once we didn’t, a sense that we lacked a path forward. We had difficulty connecting with loved ones-because what if they died, too? I wasn’t the only one who always hated celebrating her own birthday, who hid in her room when she got her first period, who waffled on marrying her longtime boyfriend, who squirmed when someone called her a woman because she felt like a child. We all dreaded Mother’s Day.

We were asked to remember anecdotes about our mothers and then use them to introduce our moms to each other. The details of our relationship, of who she had been, came flooding back. I told the group how my mother bought me my first Nancy Drew book at an Albertsons grocery store, and how I’ve loved mysteries ever since. One woman’s mother enrolled her in dance classes, in hopes she’d become a Rockette.

Another mom sent multiple gifts with her daughter to birthday parties so siblings weren’t left out. Since we were of varying ages and circumstances when our mothers died, some relationships were more complex-a few had been teens, and they remembered conflicts they’d had with their mothers, while others were too young to form concrete memories at all. I felt grateful for my kind, sunny mother; I felt even more grateful to be able to remember so much of her.

In one exercise, we were asked to hold up our mother’s photo and say our name, and also hers. I wasn’t prepared for this. I hadn’t said my mother’s name in years. As my turn neared, my heart thudded in my ears. I didn’t know whether I could get the words out. But I did. I said, “I’m Kris, daughter of Penny.” Speaking of her this way made her a person again-not a memory, or an illness, or a taboo subject that made others feel awkward. I began to cry, and looking around the room, I saw that everyone else was crying, too.

Before heading home, we discussed goal setting, self-care, staying in touch. We did a “cinnamon roll” hug-everyone standing in a line, holding hands, and then, starting at one end, spiraling into each other. Group hugs are not exactly my thing, but this was nice, because these women were now my friends.

There’s no getting over this kind of loss. But I’ve been given tools, a community, a path back to the vibrant version of my mother, to whom no grief is attached.

Not long after the retreat, I celebrated Mother’s Day for the first time. I’ve celebrated it every year since.

Pump Up the Volume

Molly Guy teaches her daughter the art-and the necessity-of sounding off.

Recently, I chaperoned a field trip with my daughter’s first-grade class. On the school bus, the girl sitting beside my child began berating her. She called her a copycat, alleging that my daughter had sneaked a peek at her worksheet. In response, my daughter looked out the window and cried. Hard. You should know a few things: (1) She is not a crier. (2) The girl just sat there, smug as a snake, and never said sorry. (3) I did not intervene. I thought if I did, it would make my kid look like a wimp.

I know why she was crying. My daughter prides herself on doing the right thing. Being accused of breaking a rule freaks her out to the bone. So her body reacted, not her brain. It was too much for her mind to bear.

At dinner that night, I said, “I know it sucks to be called a copycat. But if someone yells at you for something you didn’t do, try to get brave.

Breathe in slowly, make your chest big like a lion’s. Use your bold voice. Tell the girl, ‘That’s not true. I don’t like when you talk to me like that.’”

She climbed into my lap. She was listening.

What happened on the bus was a small thing-but small things can become big things. Growing up, when I went to Supercuts and the hairdresser put the dryer on high, burning my scalp, I never said, “Please turn that off.” I was worried I’d hurt her feelings. In eighth grade, I got my period all over my jean shorts while my dad drove me to tennis camp. Instead of asking him to pull over so I could change-which required saying something uncomfortable-I showed up at orientation looking like I’d partaken in a massacre. In college, I had one-night stands in which the sex was bad, rough, painfully so; as writhing frat boys left marks on my body with their hands, I pretended I was having fun.

I was a girl who kept quiet at all costs. It takes a long time to unlearn that. I don’t want my daughter to go through life with sealed lips when something hurts. I don’t want her to turn inward when her integrity is on the line.

The next time someone tells my daughter, “You’re doing it wrong,” I hope she looks that person in the eye and says, “I’m doing it the way I want to do it.” The next time someone hurts her feelings, I hope she says “You hurt my feelings” and walks away. I hope she says it loudly. I hope she says what she needs to. I hope she says what I didn’t.

The Double-Edged Mother

She could be cruel and thoughtless. Or magnetic and loving. Now that her mom is gone, Amanda Avutu chooses which version to remember.

If I ever wondered what my mom wanted for Mother’s Day, all I had to do was visit the fridge and look at the list, written in her exquisite cursive, she’d made for us kids. The first item: L’Air du Temps-or, for those of us who couldn’t yet read, a glossy photo of the perfume cut from a magazine.

She was all want, my mother. Particularly when it came to attention. For that, her hunger was insatiable.

There were four of us kids, plus my dad. If one didn’t give her what she desired, she’d move on to the next. If it was your turn, she’d whisper in your ear while everyone was sleeping, “C’mon, let’s go get some coffee!” and you’d know she meant eggs and Taylor ham at the diner, and that there you’d hear some small, revelatory detail about her life that she’d entrust to you and only you. In that moment, nothing else existed.

Not the time she slammed you into the wall for eating leftover Chinese food in their air-conditioned bedroom (the house’s only air-conditioned room) because you knew she was on a diet and the smell made her hungry. Not the time she forgot about pickup and left you at school for hours. Not the time she swore you weren’t invited to that birthday party because, you now suspect, she just didn’t feel like taking you. None of it mattered. She had chosen you, and you were magnificent.

For years I tried to address these injuries-the college financial-aid

forms she never filled out; the high tea bridal shower she insisted on planning, during which she consoled me because she hadn’t invited any of my friends-but that was impossible: Either she didn’t remember these events or wouldn’t allow herself to. It was like arguing with an amnesiac.

The solution, it turned out, was death. At 59, my mother suffered a massive heart attack and died several weeks later. I left the hospital one night and she still existed; I fell asleep, woke to a telephone call in my darkened bedroom, and learned she no longer did.

On a rainy September day, we gathered to bury the mom who had hurt me repeatedly, deeply, forgetfully. That was when my own amnesia began to lift: I remembered good things, not just the bad. I remembered the mom who taught me to add a pat of butter to tomato sauce, who befriended every waiter who served her, who made a pros-and-cons list with me when I was deciding which job to take after college, who invited lonely strangers to our Thanksgiving dinners. This was the mom who put a map on her wall when I drove across the country and used colored thumbtacks to track my route, accepting my collect calls the whole way. The mom who could make me believe I was wondrous because she was looking at me, smiling, offering me an adventure. This is the mom I chose to save.

In one memory, it’s dark out. I have homework. I know the gas is expensive. “Let’s go for a drive,” she says-her antidote to any pain, this time mine. She backs out of the driveway and onto the main road, throws the car into drive, cranks up “Space Oddity.” Soon instead of houses there are trees, then only blackness. My mom and I are hurtling through space, singing.

I loved her then with wild abandon, with no hurting or wanting between us.

Now every time I belt out “Magic Man” like she did, or befriend my waiters, I’m choosing the best version of my mom. I conjure the best grandmother for my children. I make her magnificent.

The Great Escape

After an unhappy marriage, Meghan Flaherty’s mother cut fully, gloriously loose.

"I’ll never have sex again.”

This is what my mother told me after my father left her. We never had an orthodox relationship. She was not even technically my mother; she did not originate the role-the woman who did disappeared when I was 8-but she took it on and made it hers. I had not always been an easy charge, but we each had a lot of love to give and spoiled the other with our excess. We were not a family for boundaries. When I was a child, she told me sex was something beautiful and full of love, between adults. She wanted me to know the names for all my parts and how to keep them ventilated. (My vagina, she explained, was a glory organ-befurred; autonomous; self-cleaning, like an oven.) I grew to womanhood with a hearty view of sex, albeit more in theory than in practice.

My mother did have sex again. She had a whole heroic renaissance. At 50, divorced and terrified, she moved to Florida with no job, no plan, no résumé, no health insurance. She shed 40 pounds of unhappy-marriage weight and set about frolicking in the pleasure gardens of the Treasure Coast. She got a minimum-wage gig at a country-club spa and fitness center and made friends with everyone, from CEO to groundskeeper. She went blonde, exfoliated, face-masked, painted her nails screaming coral pink. She flounced about in floral prints, bedazzled sandals, her hair frizzing in the humid nights.

And she had love affairs: with bartenders and married men, with a trumpet player, an architect, a film director, and a hockey coach. She had wild sex, she told me, in her bed and theirs, in other people’s swimming pools, in hammocks under big fat starry skies, on Skype. She ransacked Victoria’s Secret clearance tables and brought home jungle-print lingerie by the pound. She got Botox with a Groupon. She started getting regular Brazilians.

I was thrilled for her (minus the waxing, which I viewed as a betrayal of our code). I enjoyed her exploits mostly secondhand, living, as I was, a cloistered life in New York City. After my share of loveless sex and sexless loves, I’d finally found the man I would marry and settled into monogamy. I was in grad school, reading, writing, drinking pots of tea. My mother and I would chat as she was running out for drinks, a country concert, cougar night; I’d be at home in pj’s, listening to a violin concerto, about to go to bed. I wore shades of gray to all her neon pink.

She joked that I was living out her 50s while she lived out my 20s. She wasn’t wrong. She went to piano bars, wrote amateur erotica, drank Champagne, swam naked off her apartment complex dock, and generally cavorted like a woman half her age-right up until she died in a car crash at age 58, in the passenger seat of her boyfriend’s SUV.

Now that she’s gone, I try to sparkle more, behave a little less. I remember how she used to refer to me, her then-20-something daughter, as the fun police, far too serious and staid. Live a little, she would taunt. And I would knock back a tequila shot and dive after her into the sea. There were times I felt I had to be the mother, to drive her home after a few too many pineapple flirtinis at the Breakers bar, help her stumble into bed and try to feed her water, ibuprofen, a banana before she fell asleep. But I cherish those times; I was thrilled to see her come alive. And now, at 35, I have so few regrets about my 20s. I gave them to my mother, and she lived them well.

This story originally appeared in the May 2019 issue of O.

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.