How the First 'Star Wars' Novel Almost Spoiled the First 'Star Wars' Movie

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

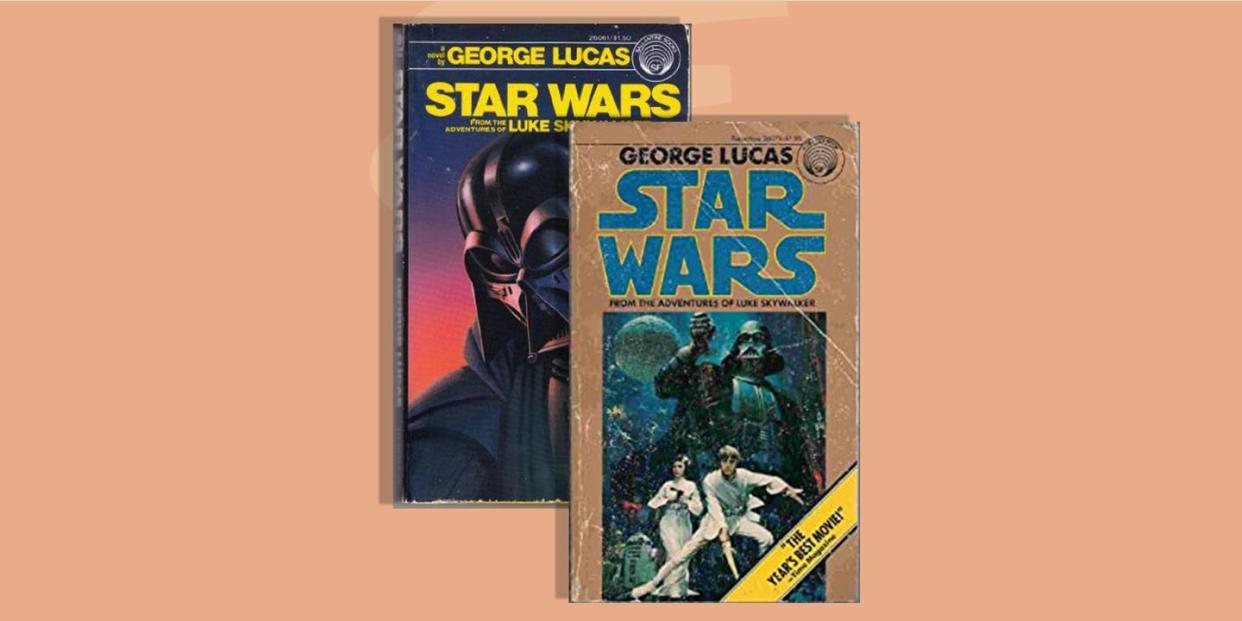

The first bad review of Star Wars came from a book critic. “The novel is a huge cliche,” S.W. Schumak wrote in the pages of Cinefantastique in the November 1976 issue. “And a poorly written cliche at that.” To be clear, Schumak wasn’t reviewing the 1977 film Star Wars, later retitled by George Lucas in 1981 as Star Wars: Episode IV—A New Hope. This early and less than enthusiastic take was a review of the novelization of the 1977 film, a book published by Ballantine on November 12, 1976, six whole months before the public saw Star Wars. The book’s full title was Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker, and to this day, it carries the name “George Lucas” as its author. But George Lucas didn’t write it—a ghostwriter named Alan Dean Foster did—and the world was never the same. Forty-six years ago, this unique piece of Star Wars ephemera spoiled the plot of the biggest movie of all time, even though only hardcore cinephiles and sci-fi fans noticed.

Now, let’s not get it twisted. The film version of Star Wars is not secretly based on a 1976 book by Alan Dean Foster. Even though the book came out before the movie, Foster was hired by George Lucas to write a tie-in novelization of Lucas’s screenplay. The book hit shelves early because Star Wars, the film, was late. 20th Century Fox initially wanted Star Wars in theaters for Christmas of 1976, but because of production delays largely connected to the incomplete visual effects, the film was pushed back to May 1977. This meant that Alan Dean Foster’s Star Wars book, with George Lucas’s name on it, had an entire life of its own for half a year, before the Force was famous.

As a science fiction writer in his own right, Alan Dean Foster was very familiar with the strange tap-dance of turning movies into books. He’d written the novelization of the 1974 sci-fi movie Dark Star, as well as several Star Trek Log books, all of which adapted episodes of Star Trek: The Animated Series (1973-1974) into short stories. And, as was a common practice at the time, Foster had to write the book version of Star Wars—all 220 pages of it—without seeing the movie or having any sense of what the characters even looked like.

“I had met Mark Hamill and knew what he looked like,” Foster revealed in Edward Gross and Mark A. Altman’s oral history book Secrets of the Force (2021). But other than the face of Luke Skywalker, Foster had to be “nebulous” about the physical appearance of Chewbacca, who is only described as “a great hairy mass,” in the book. When not being vague on purpose, Foster based the vast majority of his visual descriptions on his own imagination, the script itself, and the pre-production concept art, painted by the legendary Ralph McQuarrie. “The feeling of the film was there in the paintings and that’s all I had to work with,” Foster said.

Never out of print since its publication, this novelization of Star Wars stands apart from all other Star Wars books in one specific way: despite following the plot of the film pretty closely, the book’s aesthetic seems to come from an alternate universe. In this world, the Lars family farm isn’t just a moisture farm, but rather a real farm, as Luke reflects that the Tatooine sand “would blossom with food plants” during the harvest. Later, the description of the famous Skywalker lightsaber is simultaneously incorrect and strangely compelling. When Luke is first given the lightsaber by Obi-Wan Kenobi, Foster writes of a “gizmo” that “consisted of a short, thick handgrip with a couple of small switches set into the grip.” This “innocuous-looking device” has a “small post with a circular metal disk,” along with “a number of jewellike components built into both the handle and the disk.” If you think this lightsaber description sounds strange, this is just the microcosm for understanding the way that the 1976 novelization of Star Wars feels for those of us who read it after the film—which, at this point, is pretty much everyone. In the same scene, Obi-Wan says, “Even ducks have to be taught to swim,” to which Luke replies, “What’s a duck?”

Nitty-gritty differences in the novelization have fascinated hardcore Star Wars fans for decades. Instead of Red Squadron attacking the Death Star, the X-wing group is “Blue Squadron,” while the Y-wing bombers are “Red Squadron.” In the 2016 film Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, we did get to see Blue Squadron, though not the way they are described in this book. Here, Luke can actually spot the number and color designations on the sides of the ships, especially when Biggs (Blue Three) is in trouble.

There are other big, canon-shaking things, too. Obi-Wan tells Luke that “Vader used the training I gave him and the Force within him for evil, to help the later corrupt Emperors,” implying there might have been a series of corrupt Emperors who weren’t really in charge, but rather, manipulated by dirty Darth himself. Meanwhile, Jabba the Hutt (not yet “the Hutt”) is maybe/maybe not a human character in this book, described by Foster as “a great mobile tub of musical and suet topped by a shaggy scarred skull…”

Lucas did film a human version of Jabba the Hutt’s scenes with actor Declan Mulholland in 1976. These were later transformed into a digital slug Jabba for the 1997 Special Edition rerelease. But because Jabba’s true appearance was in flux in 1976, and Foster had no idea if Jabba was human or not, the vague descriptions in the novelization almost suggest that Lucas got some Jabba ideas from this book, rather than the other way around. Foster never calls Jabba a man outright, and later in the same scene with Han Solo, he refers to the gangster as a “gross form.”

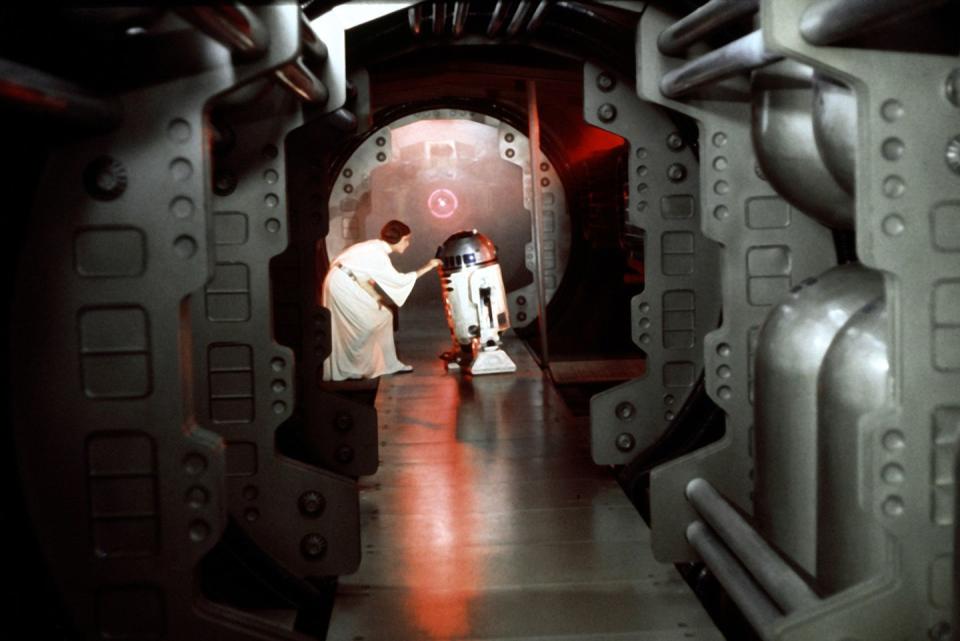

Speaking of things that are a little gross: because nobody told Foster that Luke and Leia were really secret siblings, the entirety of the book reads with clear romantic overtones, which all suggest that their love will blossom in future Star Wars installments. The book ends with Luke, having just received his medal for blowing up the Death Star, totally head over space boots for the princess. “He found his full attention occupied by the radiant Leia Organa,” Foster writes. “She noticed his unabashed stare, but this time, only smiled.” When Lucas commissioned Foster to write a book sequel to Star Wars, which became the novel Splinter of the Mind’s Eye (1978), those romantic overtones continued, with Han Solo nowhere in sight. In fairness, the idea of a love triangle between Luke, Han, and Leia is heavily implied in the actual 1977 movie, continued in the Star Wars Marvel comics series published after 1978, and remained a powerful theme in early drafts of The Empire Strikes Back.

But let’s face it: plot inconsistencies and retroactive family tree affiliations are par for the course in all of Star Wars. The divergent canon of the 1976 Star Wars novel isn’t what makes it interesting. Silly non-canon things are a dime a dozen in Star Wars. Instead, it’s the feeling and tone of the book that make it scan as delightfully anachronistic, even though it happened first. Foster’s writing reads like what would happen if a writer attempted to emulate the space opera styles of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter books, with a dash of spice smuggling stolen from Frank Herbert’s Dune. The experience of reading this Star Wars isn’t anything like watching the movie. It’s like watching the movie remade as a pulp sci-fi adventure from an era much older than Star Wars itself.

But this throwback feeling is also an accurate portrait of how the literary science fiction world regarded something like Star Wars before it existed. Because Star Wars was cinematically ahead of its time, we all tend to forget that it was thematically retro. As a 1970s sci-fi writer with a background in the genre’s familiar trappings, what Foster did was nothing short of brilliant. With just a script and some concept art, he reverse-engineered his sci-fi experience and sketched out a fantasy world that perhaps didn’t belong in prose at all. Or rather, belonged to the prose of an era much earlier than the 1970s. As Schumak’s takedown in Cinefantastique points out, “[the] climatic space battle has been done better a hundred times in prose science fiction.” At that time, most of those prose examples—like E.E. Smith’s The Skylark of Space (1946)—were thirty years old.

Still, even Schumak was prescient enough to know that this book might not accurately predict the movie it adapted. “Despite these faults, the Star Wars film could be sensational,” Schumak wrote. Ironically, Foster wasn’t nearly as confident that Lucas’ vision in the screenplay would ever click with a mass audience. “[I thought] this is actually science fiction; it’s never going to be a success,” he said. If you think people clash about Star Wars online today, just think—six months before the first movie even came out, the guy who wrote the novel version didn’t think it was going to work as a film, and a critic who hated the book thought it might be great.

Once Star Wars hit theaters, Alan Dean Foster’s career was solidified forever. In 2017, the author revealed that back in 1978, George Lucas actually expanded his book contract to include more royalties on the book rather than less. “I was sitting in a meeting one day discussing Splinter of the Mind’s Eye and George just said, ‘Oh, by the way, I’m giving you half-percent royalty on the novelization,” Foster said. When pressed, Foster made it clear that George Lucas revised his contract for the book because Lucas felt “I did a good job on the novelization.”

Although Foster didn’t think this would “amount to anything” in 1977, of course, it amounted to quite a bit. In fact, in 2020, Foster and the Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) confronted Disney after the studio retroactively withheld royalties from Foster. This issue has been subsequently resolved, and now, Foster’s royalty contract relative to the first Star Wars novel is back to the way George Lucas intended it. “He didn’t have money to throw around at that time either. Quite the contrary,” Foster told me. “He was a regular guy who happened to make movies. And I haven’t changed my opinion of him since.”

As various fandoms endlessly debate about what is and is not considered “canon,” the earliest public version of Star Wars still stands as a wonderful reminder of how fluid all this world-building really is. Although Foster’s version of Lucas’ vision was implicitly not the “real” Star Wars of “canon,” Lucas endorsed this version publicly, but also privately. At that time, the amount of corporate interest in internal continuity relative to a fictional universe’s canon simply didn’t exist. Foster has seen the change from both sides. He’s now written several contemporary novelizations, including the 2015 novel version of The Force Awakens.

“When I did the [1976] novelization of Star Wars, George read the book and said, ‘this is fine,’” Foster told me in 2017. “It doesn't work that way now. Disney spent $2.1 billion to buy Lucasfilm and they want their money back and they're being very careful with their property. I have no problem with that. It just makes it harder to write when you have to worry about the design of some stormtrooper's belt buckle.” Today, writers of tie-in fiction taking place in any kind of shared continuity have to consult with the franchise owners quite a lot. Mike Chen, writer of a 2022 Star Wars novel called Brotherhood, told me earlier this year that although Lucasfilm gave him a very free hand to tell his story, in terms of unrevealed plot points in upcoming films or shows, “It’s a one-way street of information with [Lucasfilm].”

Throughout its fascinating history, rough drafts of Star Wars have often coexisted alongside the so-called finished versions. A cynical fan might laugh at the 1976 Star Wars book and read it all as a mistake, or a misguided rough draft. Today’s more well-oiled franchise machines are more consistent—right? And yet, just as Obi-Wan tells Luke that the Republic lost something when they stopped using lightsabers, the franchise lost some of its charming messiness when it went corporate. It feels slightly sad that we’ll never get a book like the 1976 Star Wars novel again. This book isn’t beautiful and compelling in spite of its flaws—it’s so readable and so fun because of its incongruities. Because you know the film so well, reading this book creates a kind of tension, and then you smile when everything aligns. If you read the 1976 Star Wars novel in 2022, it might retroactively make contemporary canon debates seem silly. You could say that reading this book now might even balance the Force, forty-six years later.

You Might Also Like