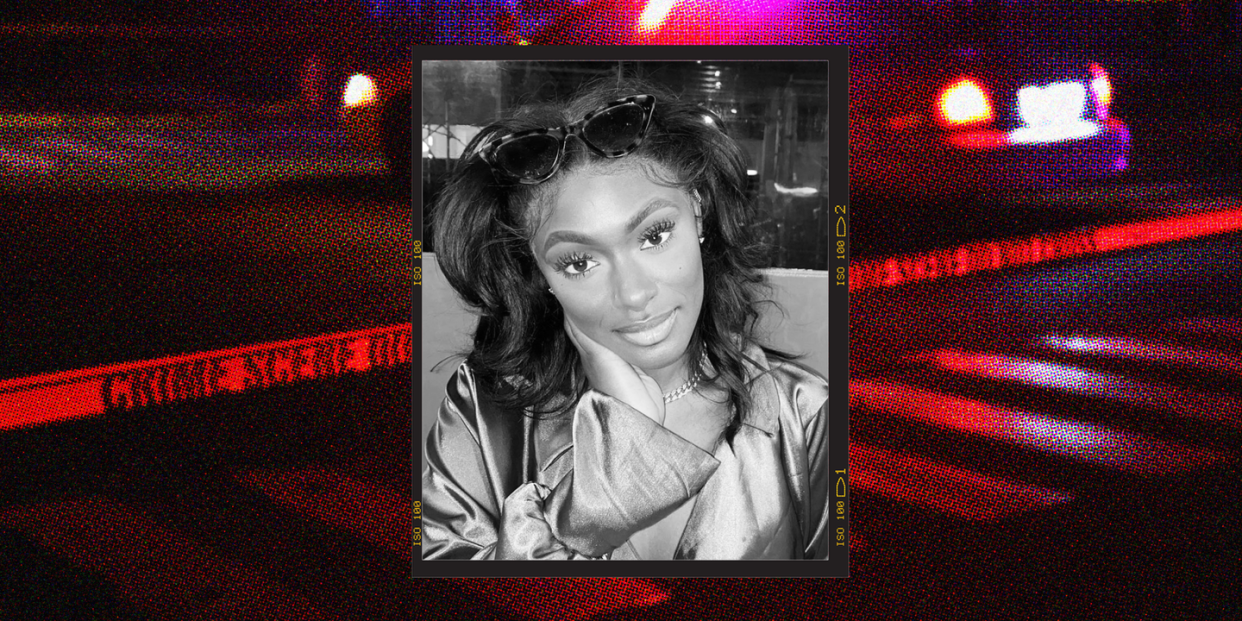

First the Police Failed Lauren Smith-Fields. Then the Media Finished the Job.

There is nothing unremarkable about the death of Lauren Smith-Fields.

Last December, the 23-year-old was found dead in her apartment in Bridgeport, Connecticut, following a date with a man she’d met on Bumble. And yet her family learned of her death almost two days after the fact, not from local police but from her landlord, who had reportedly left an unexceptional note on her apartment door: “If you’re looking for Lauren, call this number.” For weeks, a police department that vowed to protect and serve decided to neglect and swerve, dragging their feet, hanging up on Smith-Fields’s family, and depriving them of any time to grieve as they raise funds for their own costly investigation and strategize media outreach.When asked why authorities in Bridgeport hadn’t notified the family, detectives told Smith-Fields’s brother Tavar Gray-Smith they didn’t need to because “we had her passport and her ID, so we knew who she was.”

As for Matthew LaFountain, the man last seen with Smith-Fields? A “nice guy,” according to another detective. The medical examiner’s ruling? An accident caused by a mixture of drugs, despite not knowing where the drugs came from or how they were ingested. Nothing to see here, folks.

But then why, nearly two months after Smith-Fields was found unresponsive in her home, have police launched a new criminal investigation into her case? Because an outpouring on social media and coverage in select Black-centered press amplified the cries of Smith-Fields’s family and flooded the internet, pressuring and shaming local authorities and the media into doing what they should have done in the first place. Many reports have rightfully skewered Bridgeport police for not only delaying the investigation but also failing to notify the family of Smith-Fields. In fact, two of the Bridgeport detectives assigned to the case have been suspended following an internal investigation. But I’ve yet to come across a story or article holding the media accountable for their own mishandling of this story. From radio silence to gendered racist coverage, the media absolutely failed Lauren Smith-Fields and, in doing so, continues to jeopardize the safety of Black women everywhere.

Local media coverage helps to get traction on cases from local authorities, but like many endangered or deceased Black girls and women, Lauren Smith-Fields didn’t receive much local, city, or state coverage until several weeks after her death. Connecticut Post first covered the story with a syndicated Rolling Stone article on January 16 before publishing an original report with family interviews and quotations three days later. The Bridgeport Daily Voice first covered Smith-Fields’ death on January 19, but the article was aggregated from Rolling Stone Magazine and the Associated Press coverage. Of course, this is consistent with the huge disparity between media coverage of white victims and Black victims, which fuels and perpetuates the long-standing American falsehood that Black lives are disposable. “No one is going to discard my daughter like she’s rubbish,” declared Smith Fields’s mother at a recent rally held on her daughter’s birthday. “She’s not rubbish. She had a life.”

“No one is going to discard my daughter like she’s rubbish” - Shantell Fields, mother of #LaurenSmithFields, emotional at a rally in #Bridgeport on what would have been Lauren’s 24th birthday @WTNH pic.twitter.com/p22YXs8jb8

— Lauren Linder (@lauren_linder) January 23, 2022

The 2021 disappearance of Gabby Petito and the widespread, nonstop coverage her case received shined a glaring light on this gap, highlighting the privilege white women receive at the expense of every other woman. “Gabby Petito was missing and the type of manhunt that was out for her killer was insurmountably different,” the Smith-Fields’s lawyer, Darnell Crosland, argued. Recent docuseries like Black and Missing on HBO Max and Unsolved Mysteries, along with independent platforms like Our Black Girls, reveal that Black girls and women go missing at a significantly higher rate than those of other groups. In 2020 alone, Black girls and women accounted for nearly 34 percent of the 268,884 girls and women reported missing, although they made up only about 3 percent and 12.9 percent of the U.S. population in 2019, respectively.

“Missing White Woman Syndrome is the tendency to engage in national panic when a white woman, especially when lovely to look at, goes missing,” said journalist and author Deborah Mathis in an episode of Black and Missing. Every development is covered, every person of interest, suspect, and court proceeding. “The country has a conniption.” Murdered Black women remain just as vulnerable and underreported, as proven with Smith-Fields and—a name we’re guessing you haven’t heard much about—Brenda Lee Rawls, a 53-year-old Black woman whose body was found in the same city on the same day as Smith-Fields’s. Police failed to notify Rawls’s family too. Of the 3,573 women murdered in 2020, 1,440 of them were Black women, according to FBI reports, with the rate breaking down to at least 4 murders per day.

All of this stems from a long-standing history of bias in the United States media. For centuries, Black people and white people have not been depicted the same, from minstrel shows and Birth of a Nation to Bravo reality shows and The Help. In the case of Black women, we’ve faced decades of misogynoir, or misogyny directed toward us, in American visual and popular culture. Films and then television portrayed us as stereotypical archetypes, mainly the nonthreatening, obedient Mammy; the aggressive, overbearing Sapphire; the tragic, emotionally unstable Mulatta; and the lascivious, hypersexual Jezebel. Those then evolved along the years to the scheming, shiftless Welfare Queen; the desperate, spiteful Baby Mama; the unreasonable, overbearing Angry Black Woman; the predatory, soulless Gold Digger; and the hard-partying, uncultured Ratchet Woman, among others, whereas white women continued to represent innocence, purity, and beauty.

Clearly leveraging this tradition of misogynoir, the Daily Mail Online tweeted an article on January 19 captioned, “EXCLUSIVE: Pictured - Design engineer, 37, whose Bumble date, 23, died in her bloodstained bed next to him.” The tweet positioned a high-resolution photograph of a bespectacled LaFountain fully clothed against a picturesque blue sky beside a low-resolution photograph of Smith-Fields wearing a coy smirk and a string bikini, her hand outstretched toward the camera.

EXCLUSIVE: Pictured - Design engineer, 37, whose Bumble date, 23, died in her blood-stained bed next to him https://t.co/6bQyxTcsUk

— Daily Mail Online (@MailOnline) January 20, 2022

The actual article admittedly does offer wider coverage into the story of Smith-Fields’s death. But consider this: According to a 2016 study by computer scientists at Columbia University and the French National Institute, 59 percent of links shared on social media are never clicked on at all. In other words, in the age of sharebait, people are more willing to share a news article than actually read it, which means that many times, the headline is the story. Cardi B peeped the glaring contrast in Daily Mail Online’s headline and photo choices and tweeted, “Naa this man don’t look old and it’s not old at all and yet the media made it seem like she was wit a old ass man lookin to trick on her. I’m disgusted on how they spin the narrative specially because I see people saying online ‘that’s wat she gets.’”

Naa this man don’t look old and it’s not old at all and yet the media made it seem like she was wit a old ass man lookin to trick on https://t.co/2btR6XvluQ disgusted on how they spin the narrative specially because I see people saying online “that’s wat she gets” pic.twitter.com/JeEwY6tYaY

— Cardi B (@iamcardib) January 23, 2022

Even the outlets that first reported on Smith-Fields’s death—notably outlets that center Black audiences—complicated matters with their choice of words for headlines, both helping and hurting the reach of Smith-Fields’s story: “YouTuber Found Dead After Date With Older Man She Met on Bumble,” reported celebrity news website Baller Alert on December 21. On December 24, The Grio reported, “Bridgeport woman found dead in apartment after meeting older white man on Bumble,” and a few days later, Complex reported, “Family Speaks Out Over Investigation Into Lauren Smith-Fields’ Death After Meeting ‘Older White Man’ on Dating App.” These headlines helped because Black people who raised alarms about Smith-Fields were incited by the obvious tradition of white men getting away with harming and killing Black women. But the emphasis on her being a Black social media influencer, a nontraditional job that’s not taken particularly seriously by the wider public, and his being a white man 10 years her senior with a professional and presumably well-paying job also reeked of misogynoir and stoked assumptions about the nature of their relationship. These headlines called into question Smith-Fields’s motives more so than his.

This isn’t to shade the Black journalists who covered Smith-Fields’s story, even those who reported weeks after the fact. Because many of those journalists were the first to report on the story in their respective publications. This speaks to a larger institutional and systemic issue. How many newsrooms are led by Black journalists? How much coverage and how many editorial strategies are determined by Black women, specifically? Even in those media workplaces that tout high rates of diversity and inclusion, Black leaders are likely a scarce minority in those spaces, already stretched thin and overextended. We can’t and shouldn’t have to cover everything.

This is why we still say representation matters long after the Oscars have aired. The year is 2022 and white people are still overrepresented as innocent, human victims, whereas Black people are overrepresented as impoverished, dangerous, inhumane criminals. As Mathis pointed out in Black and Missing, “If you have been bombarded your entire life with messages and images of Black people being poor, down and out, dangerous, it is no surprise that when a Black person is in distress, murdered, it’s not a big deal to much of white society, because they don’t think we have much to lose.” That’s why many people think Black people are to blame for the things that happened to them. Lauren Smith-Fields was blamed for having a man from a dating app in her apartment and sharing posts about sugaring and dating white men exclusively. (We’re not going to support those comeuppance claims with hyperlinks.) Trayvon Martin was blamed for wearing a hoodie in the rain and for walking through his neighborhood. Ma’Khia Bryant was blamed for holding a knife and acting too aggressively even though her life was being threatened. Breonna Taylor was blamed for the company that she kept. Tamir Rice was blamed for playing with a toy gun near his home. And Korryn Gaines was blamed for defending herself and her son.

The Smith-Fields family rightfully plans to sue the Bridgeport Police for their handling of the case. Unfortunately, they won’t be able to sue the news media for the posthumous accounts of their daughter, as claims for defamation of character cannot be legally charged after death. The way that the media and police have covered the life and death of Lauren Smith-Fields is not only an issue of ignorance and insensitivity but also one of grave endangerment. Whether direct or indirect, biased media coverage supports racial and gendered stereotypes unique to Black women, while media neglect reinforces the belief that Black women’s lives don’t matter. Both of these ends justify the violence committed against this vulnerable group that, in the case of Smith-Fields, Rawls, and countless others, will likely go unpunished and underreported.

We are less than two months into the new year and already dozens of Black women and girls have been murdered or gone missing around the United States, from Los Angeles to D.C., many of whom are Black trans women who rarely receive media coverage or concern when they disappear or end up dead after their dates. It’s more important than ever that, as Black women, we continue to hold the media accountable for the problematic, destructive misrepresentation and underreporting of our community. We are newsworthy because we matter, both in life and in death.

You Might Also Like