A First Lady Undeterred

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Two women were grieving, so the schedule would have to change. It was the beginning of March, 72 hours before Dr. Jill Biden was slated to depart for a three-state swing to promote the achievements of the American Rescue Plan—the Biden administration’s $1.9 trillion pandemic-response package and one of its major legislative accomplishments to date. The idea had been for her to hunker down at the White House to prepare for the trip. Now her presence was required elsewhere—and she was in apparent need of a time-travel machine.

In Massachusetts that Friday morning, top Biden aide and White House deputy chief of staff Jen O’Malley Dillon was mourning the loss of her father. In California later that same day, Senator Dianne Feinstein was holding a memorial to mark the passing of her husband, Richard Blum. Both men had died of cancer. Their loved ones were heartbroken. The services were thousands of miles apart. Scrap the quiet weekend. “Things change so fast. You have to be flexible,” Biden says now, “or else you won’t survive the job.” Dr. Biden would zip up to Boston and then book it to San Francisco. Two funerals. Two coasts. One woman with a three-hour time difference on her side. She made it.

In November 2020, when Joe Biden was elected president, the win seemed to validate not just his decision to enter this race but his entire career in politics. He has been grieving in public since he was sworn in to the United States Senate in 1973 from the hospital where his two young sons were recovering from the car crash that killed his first wife, Neilia, and their one-year-old daughter, Naomi. He married Jill four years later. Toward the end of his second term as vice president, in 2015, one of those sons, Beau, died of brain cancer. He resolved to launch this bid—his third in three decades—after watching white nationalists march on Charlottesville in 2017. The nation was sick and divided. He wanted to heal it.

When the ballots were tallied, Biden was declared the winner. But in the meantime, America had further deteriorated. It was battling one novel virus and several older ones. The pandemic had exposed long-festering discrimination and hate. Hundreds of thousands of people had died. Biden had the kind of credentials no one envies; few in politics could claim more experience with sorrow.

Pundits wrote that Joe Biden had met his moment. But Jill Biden—a patient educator in an era of rampant misinformation, a woman so determined to be present for her people that she spent one weekend in March straining the limits of the space-time continuum—was there to greet it too.

Now the moment has changed. The pandemic stretches on, with new variants making quick work of the Greek alphabet. Health-care workers are burnt out. Teachers are exhausted. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is devastating—and driving up the cost of fuel amid rampant inflation. Biden’s approval numbers have sunk into the low 40s. Several polls ahead of the midterm elections predict dire losses for Democrats, with both the House and the Senate threatening to slip into Republican control.

It’s not the kind of environment that sets an obvious course for the nation’s most scrutinized political spouse—let alone for one who describes herself as an introvert and was so lukewarm on the rites and rituals of the Washington horse race that she spent her husband’s entire Senate career at their home in Delaware. But perhaps that’s for the best. In the absence of a guidebook, Jill Biden is writing her own.

It’s a few weeks after the Boston–San Francisco scramble when we sit down in the Green Room of the White House—one of three parlors on the State Floor. A low table is set for us, but the fireplace is lit and beckoning on the opposite wall. In a pale-blue suit and heels, Dr. Biden hoists two chairs over. The German shepherd Commander, whom the Bidens welcomed in December 2021, has come down from the residence for our interview. He’s curled up in one corner. The scene is quiet and almost languorous. It stands in stark contrast to the routine that Dr. Biden is describing: the rigorous slate of meetings and teaching, the barre classes she likes to attend, dinner with her husband, the exams she marks up before bed. (Twice a week, she commutes from the White House to Northern Virginia Community College in Alexandria, where she teaches three classes and has been a professor since 2009.)

“Even as a Senate spouse, I was working, going to grad school, doing campaign events, raising kids,” she remembers. The pace is intense but not new. “Showing up matters,” she explains. “That’s the feeling I get. You’re exhausted. You just do it.” It’s a mantra that helps explain how a person who has recently returned from back-to-back funerals to remember men who died from a disease that still haunts her seems as energized as ever.

For the past 18 months, Dr. Biden has maintained a schedule stacked like a Jenga tower. She has continued to teach her English and writing classes, making her the first presidential spouse ever to maintain her own career in addition to her duties in the East Wing. Her responsibilities for what she has called her “other job”—attending events and calling attention to both the policies and priorities of the administration and to the causes that she’s championed, from education to support for military families to cancer research—squeeze around the school calendar. Papers are graded on Air Force Two; speeches are reviewed after lesson plans are finalized. And then there are her friends, her children, her grandchildren, her relationship with her husband, her relationship with herself. It’s that last bit that sustains the whole operation. She knows who she is; she shows up without losing sight of herself.

At the White House, she will set her alarm for sunrise just to steal back a few minutes of alone time. “The first thing I do is open the blinds and look out,” she says.

That week in March, she was once more launching into multistate travel—from Washington to Arizona to Nevada and back, with a two-hour touchdown in Fort Campbell in Kentucky tacked on at the last minute. Dr. Biden had lobbied for it. She wanted to meet with the families of soldiers who’d been sent to Europe to support NATO amid the war in Ukraine. The morning we depart for Arizona is the first day of spring break. School is out for the week, making this trip less constricted than usual. She doesn’t have to race back to campus for class. When she boards the plane bound for Phoenix, waving to the press corps, she’s dressed in standard-issue FLOTUS-wear: cheerful purple Carolina Herrera dress, Valentino pumps. Plus a subtle twist: a thin gold anklet on her right ankle that glints in the sun.

That first afternoon, we hit two cities and the Gila River Indian Community south of Phoenix. Each stop emphasizes one or two of the themes that matter most to Dr. Biden: education, health care, support for military and veteran families through her Joining Forces initiative, and workforce opportunities for women.

At the San Xavier Health Center on the Tohono O’odham Nation the next day, Dr. Biden notices the crowd straining to hear one of the speakers. He’s outlining a prominent partnership the clinic has secured with the University of Arizona Cancer Center. But what good are his remarks if no one can make them out? She waves him forward. Come closer! She doesn’t stop until she sees the reporters start scribbling. The teacher in her is irrepressible: She is here to make sure the administration is being heard.

In her 2019 memoir, Where the Light Enters, Dr. Biden—the eldest of five girls—recounts a picture-book childhood in Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. (She was photographed for this story not far from there, on the streets of Philly.) Her father worked. Her mother was waiting when the girls came home from school. Friends were welcome at all hours. Suitors made themselves so at home that more than once, Jill would leave for a date and see an ex at the dining-room table, deep in conversation with her dad.

At the time, none of it seemed so special: the parents who were wild about each other, their unwavering support for their children. Jill idolized their relationship. “I was raised on valiant princes and star-spangled banners,” she writes in the book. “I believed that love conquers all, that justice would prevail. I don’t think I was wrong—not in the long run—but I soon realized a lot of the details had been omitted.” Dr. Biden met the man who would become her first husband when she was still a teenager. She was 18 at their wedding in 1970. He was a few years older. Her parents adored him. They were both students at the University of Delaware. She dreamed they’d earn their degrees together. When he dropped out of college and then the relationship, no one was more surprised than Jill. She was divorced by her mid-20s and on her own for the first time.

In the White House, she grimaces as she recounts it. “I believed so much in the institution of marriage,” she explains. “When the marriage fell apart, I fell hard because of that. And for him to turn out to be who he was …” She’s about to finish the sentence when, as if on cue, Commander barks and gets into a defensive crouch.

When he quiets down, Dr. Biden continues. The divorce was emotional torment, but it had practical consequences too. She needed a place to live. She had no income. Her parents offered to let her move back home, but she refused. She scraped up enough to rent a one-bedroom town house in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, just over the Delaware state line, while she finished the courses she needed to graduate. “I knew I would never, ever put myself in that position again—where I didn’t feel like I had the finances to be on my own, that I had to get the money through a divorce settlement,” Dr. Biden says. “I drummed that into [my daughter], Ashley: Be independent, be independent. And my granddaughters—you have to be able to stand on your own two feet.”

The commitment she made to herself is one she continues to honor. With a smile, she declares herself: “I am a woman who loves to work.” She likes how her career has challenged her and what she’s learned from her students. With the exception of the few years she took off to be at home with her children, she has always had a job that paid. After a failed relationship, after she married again and her husband became a bigger and bigger force in American politics, her work remained the thing that was just her own: a safety net, a bit of personal freedom. It’s the reason Dr. Biden fumes when she thinks about the enduring inequalities that have kept women out of the workforce or from reaching their full potential. “I understand a woman’s need to have something for herself,” she says.

So she’s not thrilled that the policies she believes would most empower women have been scuttled or deprioritized in Washington. The social spending bill that President Biden had hoped would pass is on ice after a conservative Democratic senator balked at the cost (and Republicans vowed to oppose it no matter what). She has conceded that a provision she pushed for—which would have made two years of community college free for any student who needed it—won’t be included in even a revived version of the plan.

She hasn’t just read the headlines about the childcare crisis that has driven women out of the workforce; she’s also seen it in her classes. The semester she taught over Zoom, children crawled through screen after screen. “I will keep talking about childcare and pushing childcare and hoping that we get it,” she says. “Families need it—not just women. I hear that all across America.”

Sheila Casey—a friend who met the Bidens when her husband, General George Casey Jr., was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during President Obama’s first term—underscores that these concerns run deep for Dr. Biden. Whether or not a bill is headed to her husband’s desk, these will continue to be her issues.

“She did not come into the White House and say, ‘Okay, now I can do X,’ ” Casey says. “Her focus on the military, education, community college, health, wellness—she’s been doing that for years.”

Joe Biden proposed to Jill five times. The two had been introduced in 1975 with an assist from Biden’s younger brother Frank. Then-senator Biden had seen her face on a one-off local parks-and-recreation ad campaign at the Wilmington airport and pointed her out when Frank came to pick him up: “That’s the kind of girl I’d like to date.” Frank knew her—they both attended the University of Delaware—and he gave Biden her number. The first time, the second time, the third time he proposed, she wasn’t sure. She couldn’t bear the prospect of a second divorce. And she wouldn’t do it to Beau and Hunter. The thought of becoming a senator’s wife terrified her. But after the fourth time, she felt herself softening. The fifth time, he told her he wouldn’t ask again. He was headed out on a trip to South Africa. He wanted an answer when he returned. The two married in 1977. “Your life will never change,” he promised.

That, of course, turned out not to be true. “Life is change,” Dr. Biden writes in her memoir. Some of it devastating, some of it thrilling, much of it bittersweet. Her world has changed. She has had to change with it. When Biden was running for president for the second time in 2007 and 2008, Mary Doody—a fellow teacher at Delaware Technical Community College, where Dr. Biden was working—saw the toll the trail took on her friend. “She hated—and I don’t think I’m exaggerating—talking in front of people,” Doody says. “It was difficult for her. But she did it.”

Four years later, Doody flew out to North Carolina to be there for her friend at the Democratic National Convention. “I remember sitting there in Charlotte and watching her on that stage and thinking, ‘My God. She’s come a long way from when she was dreading going to Iowa to speak to 25 people.’ ”

In Fort Campbell, where we’ve arrived after tackling six events in two states in 48 hours, there’s no trace of the old Iowa nerves. Dr. Biden delivers prepared remarks to a crowd of about 50 military families with ease. The speech centers on how the administration is thinking of them—how she and her husband know what it’s like to be worried about a loved one serving overseas, given the 10 months Beau spent in Iraq. She praises the courage of those in the armed forces, but when she talks about strength, it’s the sacrifices of the people in this room on which she concentrates. “You serve alongside your loved ones,” she says.

It’s a somber note, and she strikes it. But before she steps down from the podium to mingle, she swerves with an ad-lib: “You can yell at me or you can say kind words—it’s up to you!” The crowd laughs, and the mood loosens.

Even before Beau died, Dr. Biden was the kind of person people confided in. She and Casey worked together on military issues during the Obama years, and Casey watched how her friend reached out to people. “She’s a wonderful listener,” she says. “She’s incredibly compassionate. And because she has lived it, it gives her credibility and also insight.”

But there’s no question that her instincts have sharpened since the loss of Beau. Dr. Biden walks into a room and she can just tell who is suffering. “I can spot it so quickly,” she says. “Just in their line of sight, their body language.

“There was an event [at the White House] last night—Senate spouses,” she says. “And one of the spouses—one you would never imagine—came up and said, ‘I have a friend who has what your son had.’ I said, ‘Let me write to her.’ I never probably would’ve made small talk, but yet here was something.” She will find time to write the letter. She’ll make a dent in the proverbial stack of books at her bedside. She’ll call the people who need her. “I wish I knew the actual secret,” says Doody. “I’ll say, ‘Jill, you have to watch Belfast.’ She says, ‘Oh, yeah. I saw it.’ I’m like, ‘What?’ I’m like, ‘Jill, you have to watch CODA.’ ‘Oh, I saw it. It was great, wasn’t it?’ ‘Jill, have you read The Vanishing Half?’ And she goes, ‘I love that book.’ ” Doody continues, “I say to her, ‘Jill, I can’t believe how you do this. You’re so busy!’ She says, ‘Mary, everybody is busy.’ ”

Still, Dr. Biden has her boundaries. The classroom is sacred. She has drawn a line regarding phones at the dinner table. She remains her husband’s fiercest defender—something voters glimpsed in March 2020 when she was likened to a linebacker for tackling a protester who rushed him onstage. (There’s that Philly spirit.) “I try to be a support for Joe, because I don’t know how many people are saying to him, ‘That was great. That was brilliant.’ I try to be that person for him,” she says. “Some days, I see Joe and I’m just like, ‘I don’t know how you’re doing it.’ It’s the pandemic and then it’s the war and then it’s the economy and then it’s the gas prices. You feel like you’re being slammed.”

Which is not to say that she holds back when he frustrates her. The president does not get a pass. During the Obama years, they took to hashing out their occasional spats over text to avoid fighting in front of the Secret Service. (They christened it “fexting.”)

Not so long ago, she tapped out a message to him in a fit of pique. “Joe said, ‘You realize that’s going to go down in history. There will be a record of that.’” She grins. “I won’t tell you what I called him that time.”

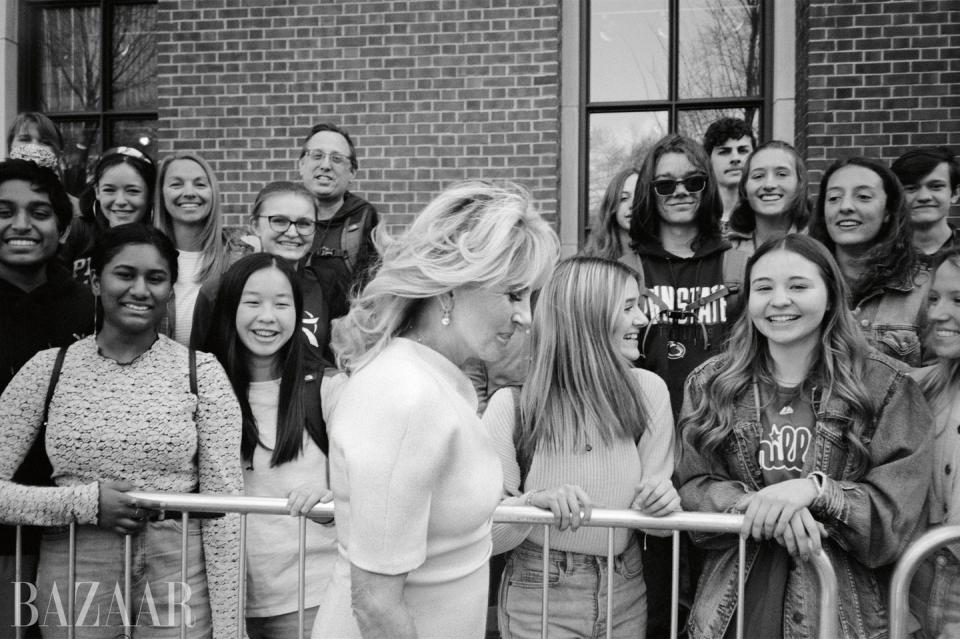

The photo shoot for this story falls on one of Dr. Biden’s favorite holidays: April Fools’ Day. The first lady is a notorious prankster. (She once shocked staffers by popping out of an overhead luggage bin on Air Force Two.) When she is handed a fluffy Dr. Seuss hat for one of her outfits, her eyes narrow until she realizes that this time, she’s been had. She throws her head back in laughter.

Dr. Biden delights in these kinds of moments. One of her granddaughters, Naomi, is engaged and planning a wedding reception at the White House in November. Another has informed Dr. Biden that she scored an internship in D.C. She wants to move in. Just for the summer! “Really!” Dr. Biden says, awed. “I’m going to be raising a teenager?” She’s just been holed up with her sisters at Camp David to celebrate a birthday. “We had our martinis and just laughed, and it felt great,” she says. Sometimes people will ask them what it’s like to have Jill Biden as a sister, a question as obvious as it is hilarious. She’s their older sister—teased, beloved, admired, revered. Dr. Biden mimics their faux horror: Please! “She’s just Jill.”

Hair: Esther Langham; Makeup: Romy Soleimani; Manicure: Gina Edwards for Chanel Le Vernis; Production: Margot Fodor at Lola Production; Tailoring: Maria Del Greco.

This article originally appeared in the June/July 2022 issue of Harper's BAZAAR, available on newsstands June 7.

GET THE LATEST ISSUE OF BAZAAR

You Might Also Like