Finding Friendship After Unspeakable Trauma

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

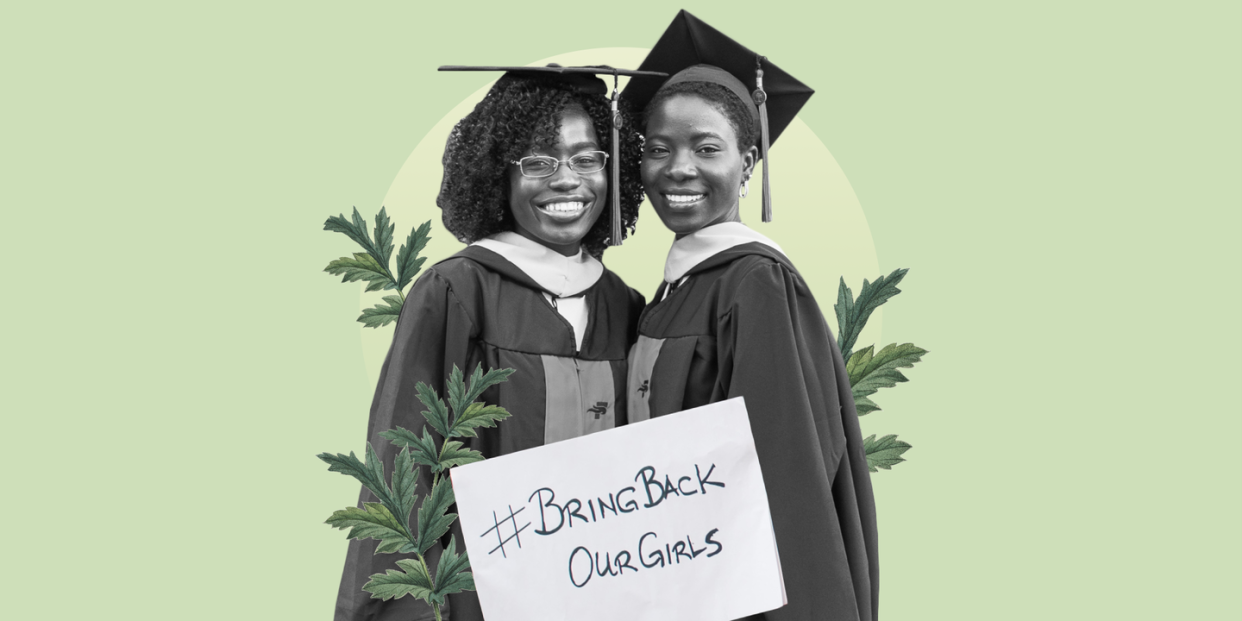

Eight years ago, in April 2014, Joy Bishara and Lydia Pogu were fleeing for their lives. They had just escaped a mass kidnapping of 276 teenage girls from their boarding school in Chibok, Nigeria, by the terrorist group Boko Haram—a crime that ignited the global social media campaign #BringBackOurGirls. The terrorists wanted to prevent the girls from getting educated. But these two would not be stopped.

This year in April, Bishara and Pogu received master’s degrees from Southeastern University in Lakeland, Florida—a dream neither could imagine in the weeks following their harrowing escape. “After what happened, I thought I would never get to finish school,” Pogu says. Amid the trauma of the abduction and fear of being captured again, school wasn’t even on her mind at the time. “I just wanted to be safe and have my family be safe.”

Since their escape, the two have become close friends, helping each other move forward, finish school, and achieve their dreams. It’s a friendship that evolved in America, as they didn’t know each other well at school in Chibok. “Something we both love is being able to look at each other and understand exactly what we need without saying a word,” says Bishara. “Lydia will always be my closest friend no matter where life takes us.”

On the night Boko Haram stormed the boarding school in April 2014, forcing the girls at gunpoint into trucks, Pogu and Bishara escaped by jumping from a truck as it hurtled through the darkness, each deciding it would be better to risk their lives than to remain in the grips of the terrorists. After the bold leap, they made their way through the dense, tangled bush, their skin getting shredded from thorns, before managing to get a ride home with strangers.

They were among several dozen girls who got away that night. More than 100 girls were later released as a result of government negotiations with Boko Haram, but more than 100 are still missing today.

Bishara and Pogu came to America to continue their education in August 2014, with help from human rights advocates including the nonprofit Jubilee Campaign. “There were a lot of culture shocks at first,” Bishara says with a laugh. She was surprised by how many kids had their own cellphones and computers. She and Pogu had grown up in modest homes in Nigeria with no running water. Pogu was struck by how many women wore pants; she was accustomed to traditional dresses. Both had to learn English—and adjust to wintry weather. Neither cared for popular American fare like cheeseburgers or pizza; they preferred noodles and rice. “There was a lot that was a surprise, but the food and cold did it for us,” says Bishara. “We didn’t eat much, and for me, I ate noodles for a whole week until a Nigerian lady came and took us to the African store.”

In 2017, they graduated from high school at the Canyonville Academy in the mountains of Oregon, having encouraged each other along the way as they navigated a new school in a new country. “School in America differs a lot; teachers are more invested in educating the students, their well-being and personal lives,” says Bishara, adding that teachers in Chibok “were not getting paid enough” to be able to invest personally in their students. Pogu agrees, noting that she liked being able to wear her own clothes to school instead of having to wear a uniform, as she did back home. Another difference, she says: “Punishments in American schools are basically detentions and suspensions, but in Nigeria, it is a whole different level; it is common for teachers to inflict injuries on students.”

The biggest hurdle was living a world away from their families. “It was so difficult being so far from them. My mom, we are best friends,” says Bishara. “My emotions were all over the place when I moved here. I had nightmares that Boko Haram was coming for my family. It’s difficult to heal when what you’re trying to heal from is still happening every single day,” she says, referring to the ongoing terror by the terrorist organization. For more than a decade, the group has reportedly killed hundreds of thousands of people in an attempt to create an Islamic state and wipe out Western influence from schools. The girls kidnapped from the school in Chibok were mostly Christian.

Bishara and Pogu helped each other through the tough moments, telling jokes and making each other laugh about “silly things we used to do back home,” Bishara says. In fact, the pair discovered while talking to their relatives back home that they are cousins. “Having Joy by my side since the beginning of us coming to America, and after we both found out that we are cousins, has helped make me feel more safe,” says Pogu. “Having her here has always and is still helping me feel a little better, knowing that I have someone I call family here.”

Both cite their faith as a stabilizing force as well. “God has opened doors and made sure that we were well taken care of,” says Bishara. “He has used so many people to impact my life in a manner I would have never imagined eight years ago.” Pogu feels the same, saying, “God has put a lot of wonderful people in my life that have helped me overcome the trauma I experienced. Even though it’s something I still struggle with, I will say I am better because of God and the wonderful people he put in my life.”

After high school in 2017, the two headed to college on scholarship at Southeastern University, thanks to a recommendation from the former president of the Canyonville Academy, Doug Wead. They decided not to room together so they could interact more with other students and improve their English skills, but they talked and texted every day, and traveled the country on occasion to give presentations, including one at the United Nations Security Council. “When we came to college, we started sharing our story a lot more together,” says Bishara. “We traveled to new places and supported each other when we cried after sharing, or when one of us was shaking after the presentation.”

They graduated from the university in 2021, an experience Bishara calls “a wonderful journey,” despite an unexpected challenge—a pandemic that sent the world into lockdown. Pogu had a rough battle with Covid, suffering from body aches and fever and losing her sense of taste and smell. “It was very stressful. I told my parents, and they were freaking out,” she says. Talking and texting with Bishara helped her feel less isolated.

Both are haunted by the memory of their classmates who have not returned home. Bishara wonders what became of her roommate Rifkatu Galang. Bishara had comforted her the night the terrorists forced the students into trucks, bound for a forest hideaway. “She was crying so bitterly, so bad,” she recalls. “She had been through surgery and was in a lot of pain. I held her; I was crying for her. Boko Haram members came and told her to shut up or they would just kill her right there. That’s still in my mind. She’s one of those who did not come back. It’s just so sad, thinking about all my classmates, not knowing how they are, where they are, who has died.”

Pogu expresses sorrow that the world seems to have moved on while the young women remain missing. The eight-year anniversary came and went [last] spring and “nobody was talking about it,” she says.

The tragedy motivated Pogu, 24, and Bishara, 26, to want to use their education to help people escape abuse and injustice, especially in their homeland. Pogu, who got her master’s degree in human services administration, is now doing fieldwork for One More Child, a nonprofit that supports vulnerable children, and is planning to study for the LSATs and apply to law school. “I want to bring justice to people in a legal way; for example, people suffering from domestic violence, sex trafficking,” she says. Ultimately she wants to start her own law firm focusing on human rights.

Bishara, who got her master’s in social work, is working at a hospice center and wants to eventually start an organization to help women in Chibok break free from abuse and lead independent lives. “Women are staying with abusive partners there because they have nowhere else to go,” she says. “If they go to their parents’ house, their parents send them back. It’s seen as a bad thing when you leave your husband.” But there’s a major barrier to building a shelter in Chibok: “Boko Haram can just walk in anytime and burn it down,” she says. “I’m trying to find some loops around that—maybe an online organization where people can donate money for people in need. Boko Haram cannot burn down a website.”

Indeed, while Boko Haram has reportedly been weakened to some extent in recent years, the insurgents continue to terrorize the country; Chibok, a town of around 66,000 people, remains under attack. “They just attack, kill, kidnap, and leave,” Bishara says. “They want to attack people when everyone least expects.”

Bishara says that sharing her story helps her heal: “Trying to make a difference, that’s how I find my joy.”

“It really has been hard and challenging, trying to push through it,” says Pogu, noting that news of violence in her homeland is always a trigger. She cites recent reports of a girl stoned to death and set on fire in Nigeria by fellow students who accused her of blasphemy. “It brings you back to the people who kidnapped us,” she says. “Sometimes I have nightmares of people attacking me. But as time goes by and I’m starting to get used to it here, I’m okay; I’m way better than in the beginning. The Bible tells us we should forgive our enemies and pray for them. I believe in that; it has been helping me. Although I do forgive them, it’s still painful.” Both she and Bishara talk to their families several times a week.

Over the years, Pogu has been home to see her family once, and Bishara, four times—a dangerous journey for the young women who defied Boko Haram. “It’s super scary,” says Bishara. “It’s not safe. But I miss home and I want to see my family. I’m careful when I go home. I don’t announce that I’m going there. By the time people know I’m home, I’ve already left.” Pogu applied for asylum in America in 2018 and was recently approved for a green card, while Bishara hopes to get U.S. citizenship through the help of an employer or local congressperson.

Both say they are grateful for the opportunities they’ve had in America. Pogu served as the student speaker at the Southeastern University commencement in April—a “bittersweet” experience, she says, as she thought of her missing classmates, but also “a huge, great honor to be able to stand in front of these amazing students. I was nervous, but it turned out great, and I was grateful I could share my journey. Afterward people said, ‘Your story is inspiring.’ I feel like I’m making a difference, and that’s my goal.”

They are also deeply thankful for their friendship. “Joy is genuine, brutally honest, caring, funny, interesting, patient with me, and the list goes on. I can tell her anything, and she is someone I can count on anytime,” says Pogu. “I know we will always be there for each other, and our friendship will last a lifetime, wherever we both end up in life.”

Abigail Pesta is an award-winning journalist who writes for major publications around the world. She is the author of The Girls: An All-American Town, a Predatory Doctor, and the Untold Story of the Gymnasts Who Brought Him Down and the coauthor with Sandra Uwiringiyimana of How Dare the Sun Rise: Memoirs of a War Child.

You Might Also Like