Finding the Bones of a Once-Enslaved Civil War Vet

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

This story is the first in a series about two families—one Black, one white—coming together to confront the wrongs of slavery.

Prologue: Searching for Her Story

The inheritance that was meant for Cheryl Wills, one that could have tempered her years of childhood pain, an inheritance that could have buoyed her spirits or brought distinction among her peers, was, in the end, locked up underground.

But Wills, a Black woman with archetypal New Yorker tenacity, was determined to find the key. It wasn’t a precious jewel collection she was after, nor was it a heap of Americana treasures from a hallowed estate. Instead, Wills traveled more than a thousand miles to western Tennessee, a land of rich soil dotted with rural homes and ranches, to search for bones in a place where, as it had been for more than 200 years, cotton was still king.

The first thing Wills noticed when she stepped out of the car on that day in November 2019 was the autumnal beauty of the land. “I immediately felt a connection to the earth,” she remembers. “I could see and touch the place where my ancestors had lived, right down to the cotton buds.” The sky was expansive, and the royal colors of fallen leaves stretched out like a carpet awaiting her arrival. “I was born in the city of steel, New York City, where things change on a dime, but I felt like I had stepped into a living museum, like I got out of a plane, got into a car, and walked into the 19th century.”

Wills’s reverie was interrupted by the warm greeting of the family living on the land today. They welcomed her to the “farm,” as many people in the South refer to land that had once been a plantation, but for Wills this wasn’t just a farm. For her, it was the site where her great-great-great-grandfather, Sandy, had toiled as a sharecropper, and his wife, Emma—Wills’s great-great-great-grandmother—had been enslaved for much of her life. It was also the place where Wills suspected they were buried. And the family that she was now meeting were direct descendants of the people who had enslaved Wills’s ancestors.

Part 1: Dyed-in-the-Wool New Yorkers

While being born Black often means being subjected to various forms of discrimination, Wills felt that growing up in New York City—specifically Queens, the most diverse of the boroughs—insulated her from the crueler kinds of bigotry many African Americans in other parts of the country endure. But the limited educational and professional opportunities that lead to a cycle of poverty were very much the same.

“My family was very patriotic. My maternal grandfather served in a segregated unit overseas during World War I. And my father volunteered to serve during the Vietnam era. But, like many Black veterans, they didn’t get the respect, or services, for that matter, that they had earned,” says Wills. “I grew up in public housing, seeing drug and alcohol addiction, people urinating in my building, a lot of violence. No child should have to see that.”

Wills’s neighborhood, Rockaway Beach, was a seaside community at the edge of the Atlantic Ocean and far away from Manhattan, the “concrete jungle” and epicenter of New York City. “We grew up with sand and water,” Wills says. “My bedroom window faced the boardwalk and the wild ocean. Sand was always in our house, and it drove my mother crazy,” she remembers. “She kept an immaculate home and made my siblings and me take our clothes off in the hallway and shower right away. When you live off the beach, the sand is everywhere.”

Wills didn’t know it at the time, but for many parents in her mostly Black “beachfront hood,” the dominant smell of saltwater, the corrosive effect of salt on furniture, the fans blowing hot sea air through homes was different from anything they had known in the American South, where many had been born. “We were the first generation of city-born kids. We didn’t know anything about slavery or country life. No one talked about it.”

When she was 9 years old, her father, Clarence Wills, a strapping man who worked as a firefighter, moved out of the family’s home and left his wife, Ruth, and five children. “I was the oldest, and I felt we were at the bottom of his priorities,” says Wills. “That cut me deeply. I was angry. I had a brother with autism, a sister who was having seizures, and a twin boy and girl that came in just as my father was moving out. I couldn’t believe the chaos that my mom was dealing with just raising a young boy with autism in the early 1970s, when it was not well-understood. She was fighting with schools and teachers who kept telling her to just throw him in an institution and forget him. My mother wouldn’t do that.” Wills’s dad, however, did not completely abandon the family. He continued to pay the bills and showed up for birthdays and holidays. “I assume he felt guilty because he was doing to us what his dad did to him, and he knew it hurt,” she says.

Four years later, Wills’s father died in a motorcycle accident on the Williamsburg Bridge. He had promised to visit the family for her brother’s birthday and then had planned to take her shopping for supplies before the first day of school. She was waiting for him by her living room window, when, at the last minute, he called to cancel. With the understandable grief and exasperation of a 13-year-old child, one whose dad had been absent and one who had watched her overtaxed mother struggle, Wills turned to her maternal grandmother and said, “I hope he drops dead.” She says, “And do you know, that night he did. I was the last person in the family to talk to my father.”

On September 11, 1980, the family came together for his funeral service. Wills sat with her four younger siblings and nearly fainted when the casket was opened. “I was stunned,” says Wills. “Surely, his head had exploded.” Clarence Wills had been zooming across the Williamsburg Bridge with fellow motorcyclists when his body flew off the bike and went headfirst into a steel beam with such force that he was unrecognizable at the funeral. When it was the family’s turn to approach the casket, Wills stretched out her arm to prevent her siblings from getting up. “We can’t look at that,” she told them, and they remained seated.

Instead, Wills focused her attention on the funeral program. That was when she read that her father had been born in western Tennessee. How come no one ever talks about Tennessee? she recalls thinking. “My father strutted around this city like he was a dyed-in-the-wool New Yorker, a badass, motorcycle-riding, firefighting Black guy. We knew he had been in the National Guard and had been the first in the family to earn a college degree, but there was not a word to his children about where he was born or how he grew up. Nothing.”

A barrage of questions would emerge over the coming months and years (“I didn’t just become inquisitive when I became a journalist,” says Wills, “and I was also nosy”), and Wills directed them mainly at her dad’s parents. “Why did no one ever take us to Tennessee?” “Who were the people in our family who were enslaved?” “Did you attend the civil rights rallies that were only a few miles from the area you were living in?” The answer to everything was an exasperated, “I don’t know.”

Back then, the exchanges just left her frustrated. But with hindsight came empathy. “You have to understand, we’re talking about a time when the descendants of enslaved people from Tennessee—the deep South—had severely limited choices. My grandparents, their parents were people who had been kept out of schools or had limited schooling and were violently beaten for minor infractions or for the color of their skin. When you experience all that, you’re in a state of fear and confusion. You’re in shock. Then here I come, from New York City, confident because I had had so many opportunities in life. I was a chatty one and was unafraid to ask questions, so many questions.” She never got the answers she sought, but that in itself was a clue to how her grandparents viewed their family history: “I sensed a shame in my family about our roots. And I wanted to know, what’s everybody so ashamed of? The shame stops with me.”

Part 2: Untangling the Roots

Wills channeled her curiosity and pain into journalism, a career that allowed her to ask questions for a living. She graduated from Syracuse University in 1989 with a degree in broadcast journalism and a profound love of the written word. She immediately landed a job at Channel 5 News as a production assistant, and by 1992, Wills had gotten her foot in the door as an original staff member at the fledgling cable news channel NY1 at Time Warner Cable, a company she helped build. “I had the incredible honor of shaping the editorial layers of the newsroom,” says Wills.

Undeterred by long hours and modest pay, she rose through the ranks by taking pivotal assignments that took her from producer to medical reporter to breaking news reporter. By 2009, the year Wills’s search for her history began in earnest, she had enjoyed 14 successful years there, including as an anchor on air. One day between shows, she sat at her desk and typed her father’s name, Clarence Wills, into the online directory of Ancestry.com. Though it was meant to be a cursory search, the dive into the genealogical platform yielded surprising and exciting results.

She found her dad’s parents as children in the 1930s census and a list of other relatives with the same last name as her father, grandfather, and great-grandfather: Wills. “I kept going through the generations and then just veered off into the wilderness,” she says. She went as far back as the 1870 census, the first census in which formerly enslaved African Americans are identified as citizens, in contrast to earlier census records in which enslaved Africans, not yet American citizens, were inhumanely lumped together as property. In those records, there were no names, only approximate ages and gender.

But she found many people with the last name Wills. “I was unsure if they were related to me because it was very common for slaves to bear the name of their owner,” even if they weren’t related by blood, she says. It wasn’t until she swabbed her cheek for genetic material to map out her biological kinships via Ancestry.com five years after her initial search that Wills had proof: “A genealogist cross-referenced the results and confirmed one name that was my relative.” That name was Sandy Wills, and he was her great-great-great-grandfather.

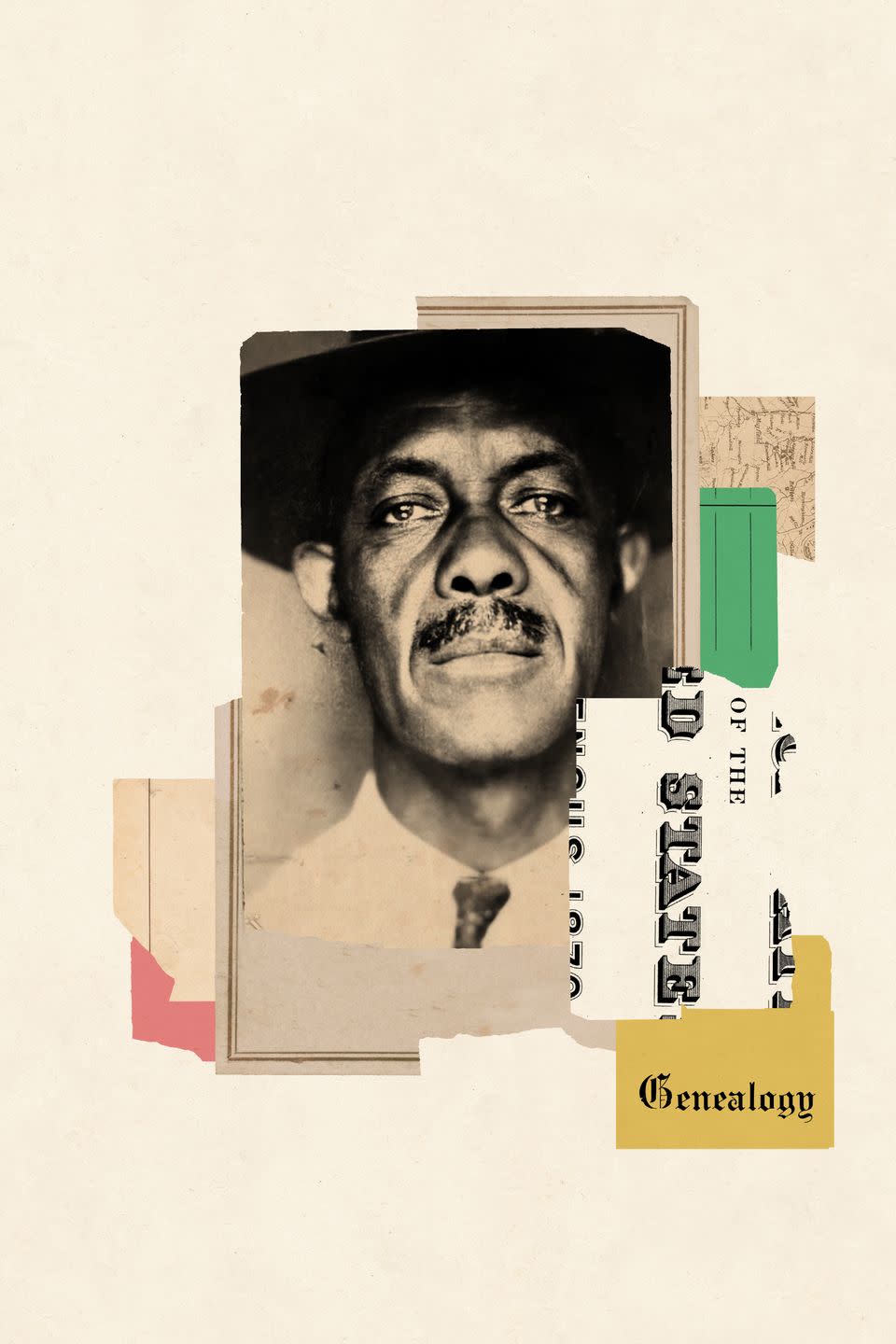

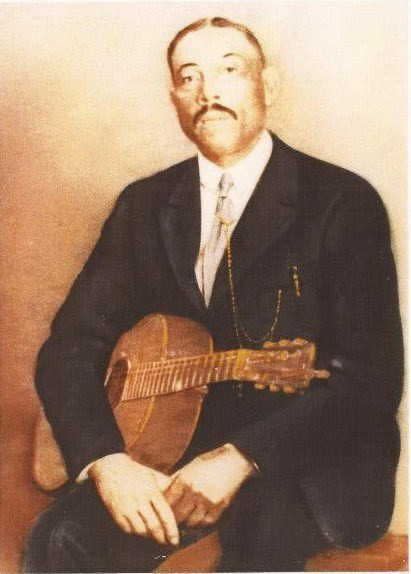

“Grandpa Sandy,” as she affectionately named him, was also, to Wills’s astonishment, a Black veteran of the American Civil War, one of the roughly 200,000 Black men who had heeded the call of famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass to liberate themselves after Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. They valiantly fought as members of the United States Colored Troops and succeeded in helping to preserve the union.

Pressing on her ancestry hunt during free moments at work, Wills commissioned a genealogy report that effectively illuminated a path through the 19th and 20th centuries, a past where her family’s pain and secrets were buried and all but erased.

Over the following seven years, Wills would deliver the news in the evening and use her mornings to pore over thousands of documents and make sense of their significance. She would catch glimpses of Grandpa Sandy in the records, such as in his marriage certificate and a receipt for a small plot of land he purchased with earnings saved while working for the Army and sharecropping. “We know he was a good family man who took care of his wife and children, who were the first generation to be born free,” says Wills. In 1863, Grandpa Sandy joined the United States Colored Troops alongside the Black boys he grew up with. He enlisted at Fort Pillow, the scene of the deadliest massacre during the Civil War. Confederate soldiers attacked the fort and killed Union soldiers, half of whom were African American, despite them surrendering. “Somehow he survived that horrific event, but I’m sure he never forgot it,” says Wills. “Every Black soldier from that moment on recited the motto ‘Remember Fort Pillow!’”

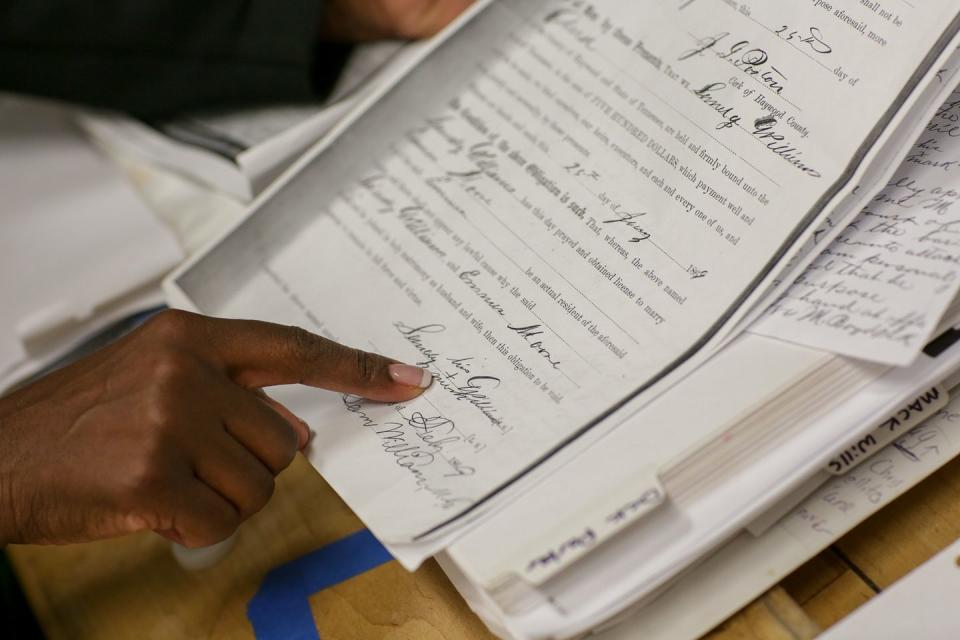

After the war, Grandpa Sandy returned to Tennessee and married Emma on the property where she had been enslaved. “We have their marriage license and pension records and a legal deposition where Grandpa Sandy states where he lives,” she says. Wills became enthralled with her great-great-great-grandmother. So enthralled that in 2020 she published an illustrated children’s book, Emma, imagining what her life as an enslaved child was like and following her into adulthood as an illiterate widow trying to claim her deceased husband’s pension, which was based on actual legal documents.

Wills also used another historical document she had discovered, an affidavit from 1890 where Emma confirmed in a sworn statement that her husband had been brought as a 10-year-old slave to the nearby Wills plantation. Says Wills, “Grandpa Sandy had taken on his enslavers’ last name as a boy; it was common practice.” In the document, Emma was explaining the discrepancy in the spelling of her late husband’s last name in an effort to lay claim to his veteran pension.

Here’s what Wills thinks happened: “When my Grandpa Sandy signed up for the war, the person filling out the form wrote down the name he thought he’d heard—Willis. Even though Grandpa Sandy was probably saying ‘Wills.’” Miraculously, Emma succeeded in persuading the Army to direct Grandpa Sandy’s pension to her, where it rightfully belonged.

The documentation was so rich that Wills had sufficient material to write several books, including Die Free: A Heroic Family Tale, a memoir chronicling the life of her father, Clarence, and of her Grandpa Sandy. She followed it with another children’s picture book, The Emancipation of Grandpa Sandy Wills, and a young adult book, Emancipated: My Family’s Fight for Freedom. Most recently, Wills wrote Isn’t Her Grace Amazing: The Women Who Changed Gospel Music. Her books, in turn, have provided a platform for her to speak publicly around the country, especially in elementary and middle schools.

At one speaking engagement at the National Archives in New York City in April 2018, Wills commanded everyone’s attention in the room except for one man whose back was turned to her. He was sitting in a corner and typing furiously into a computer. “I could hear the clicking noises he made on the keyboard,” she remembers. At the end of Wills’s presentation, the man approached her. It turned out that he was an education specialist at the National Archives and had been so enthralled by her lecture that he immediately began searching digital archives for any documentation relevant to Wills’s story while she was speaking. He handed her a printout of a document he had found; it was a copy of a sworn deposition Grandpa Sandy had given about where he lived as a free man: “I live on the widow Moore’s place.” There were also bank records, payments he made for a plot of land he’d purchased. “It showed me that he was a good steward of his money,” says Wills. “It showed me he was a visionary aspiring to a better life.”

Remarkably, the papers—receipts, tax documents, proof of the slave-holding business—came from the plantation where Emma had been enslaved as a child and where later she lived as a sharecropper with Grandpa Sandy when they married. Someone had donated them to the Tennessee State Library and Archives, and the library, in time, had digitized the documents. It turned out to be a treasure trove because it established that the buying and selling of people was the core part of the plantation’s business. “Reading these papers took me beyond journalism. My ancestors came alive for me and were speaking to me. I became an interpreter for them, and it is my duty to understand what happened to them,” she says.

Wills yearned to find Grandpa Sandy’s final resting place and to pay her respects in person. To her, it offered the chance to experience the pride that so many veterans and their families enjoy in serving our great country. But no matter how much of him she found—a few statements here and there, an X marking a signature of consent, as was customary among the unlettered—he would as quickly disappear without a trace.

Then one day, while scrolling through Facebook, Wills noticed photographs of gently rolling hills and cotton fields that transfixed her. The photos had been posted by her recently discovered cousin, Ethan, during one of his trips to western Tennessee. “I thought, Could this be where Grandpa Sandy and Emma are buried?” She contacted Ethan to find out what he knew.

Part 3: Cousin Ethan Is the Key

Ethan had a lot to say. He had made many visits since childhood to Tennessee and was intimately familiar with the landscape.

Born and raised in Elyria, a small city in northeastern Ohio, Ethan West, 43, remembers his father’s childhood home in Tennessee as being in a desolate area. “It was probably the most boring-est trip for a child to do because it was just country,” remembers Ethan. “Growing up in a city, it just didn’t register with me.” His dad, Nathaniel, had been born in 1939 in western Tennessee and made his way to the Midwest as a child with his father, George, in 1952 during the last phase of the Great Migration, a massive exodus of Blacks from the South to escape the inhumane Jim Crow laws.

According to Ethan, those trips back were happy times for his parents and filled with visits to the many relatives who remained in the rural South. By the time he was 12 years old, Ethan stopped going on the trips and stayed home with his mother, preferring to play baseball in a local league for the summer. As the years passed, Ethan’s older sister, Harriet West-Moore, began researching the family’s genealogy and reported back on the living relatives she was discovering across the United States—including, in 2010, a fifth-degree cousin named Cheryl Wills.

But before that fateful online discovery, Ethan yearned to learn more, and in 2007, he revived the tradition of making the 10-hour drive south to Tennessee with his father. This time, Ethan was 28 years old and listened carefully to everything Nathaniel pointed out: the place where Nathaniel had been born and had lived, the church cemeteries where some relatives had been buried properly, the cotton fields where he had played with his cousins and where he, too, had picked cotton as a child. There was cotton everywhere. There were fields everywhere, no signs or lights on the road. “I was amazed that Dad didn’t need no map when he was down there even though he had left Tennessee when he was 13,” Ethan says.

They also visited his dad’s uncle, Uncle Bubba, who was living in a house that looked “like it was from the 1920s and going to fall down in the next windstorm.” Ethan was in awe of his favorite grand-uncle: “He had an outhouse. He slaughtered his own pigs and chickens and had a meat house where he kept his meat, and no refrigeration. Uncle Bubba took pride in the simple life. It was cool. It was a privilege to meet him.”

After Ethan’s dad passed away in late 2012, he started taking trips on his own to research his lineage. “I was really drawn to that area where my dad was born,” he remembers. “It was as if the spirits of my ancestors were pulling me there.” Over the next three years, he and Wills were effectively working side by side—a thousand miles apart—without the other knowing. While Wills pored through records from New York, catching glimpses of Grandpa Sandy and Grandma Emma, Ethan scoped the land in Tennessee searching for traces of Dolphin West, Emma’s dad and Sandy’s father-in-law.

Ethan photographed everything and started a scrapbook, which he refers to as the “Family Lineage Bible.” He filled the book with images of the people he’d met and places he’d visited. He added notes and documents, such as marriage licenses, deed records, and Dolphin West’s sharecropper contract. “That was a jewel I found in the local county courthouse,” he says. In the sense that he fleshed out the family history, that he went back as far as he could to find the oldest living relative, cousin Ethan is the key that unlocked the mysteries for descendants of four different branches that draw a direct line back to Dolphin West and his wife, Millie.

Ethan learned that his great-great-great-grandfather Dolphin had been born in 1826 in Bertie County, North Carolina. He also uncovered records related to John Bertie Moore, the man who had enslaved Dolphin, who had also been born in Bertie County in 1808. “JBM,” as Ethan and Willis call him, came from a slave-owning family in Bertie County. Seeking his own fortune, JBM packed his belongings and made the journey west to plant cotton where the soil was fertile and the land was plentiful.

At around 9 years old, Dolphin West and possibly his mother were brought to help develop the plantation that JBM had founded. According to estate papers from Bertie County, the young boy was listed as being worth $400. Through persistent investigative work, Ethan located the plantation in which Dolphin had been held in bondage. It is that plantation that today still operates as a farm, that still produces cotton, and where Ethan was standing with Wills in November 2019 looking for their ancestors’ burial spot. And here’s the path that led to that moment.

Part 4: Wills and Cousin Ethan Connect

In November 2014, Ethan received a message out of the blue. Wills had been researching lineage channels and came across images that Ethan had posted almost a year earlier. Those photos were from his first trip to Tennessee in 2013 after his dad passed away when he discovered the property where Dolphin had toiled and had likely been interred.

Ethan: “Cheryl asked me if I knew that Emma was her three-times great-grandmother and was Dolphin’s daughter. I told her that I did know and that I had visited the county where he had been born in North Carolina. I also explained to her that I had traced my Grandpa Henry and her Grandma Emma to the farm I had photographed. I knew they had lived there, but the exact spot where they were buried was still a mystery. She was shocked.”

Wills: “You have to remember, I had already done a lot of research and written about and given lectures on John Bertie Moore and his journey west with my ancestor Dolphin. But I couldn’t locate the farm. It was like finding a needle in a haystack. The photos Cousin Ethan posted were the first I had actually seen of the land where they lived.”

According to what Wills had pieced together, after the war, Sandy returned to Tennessee and married Emma Moore where they worked as sharecroppers on the plantation where she had been enslaved her entire life. Now, thanks to Cousin Ethan’s work, Wills knew that Henry (Ethan’s great-great-grandfather) was the first boy Dolphin and Millie had. More important, Wills now knew where the former plantation was located. The more she learned about the lives of Grandpa Sandy and Grandma Emma, the more “it was about finding closure and respect for a veteran who had served his country,” she says.

Three years later, on March 4, 2017, Wills sent her friends Emanuel Robinson and Naron Tillman, a reverend, to western Tennessee to look at a dilapidated church that her ancestors had built. She wanted to investigate the overrun backyard in case it concealed a graveyard and possibly her ancestors’ remains. “At this point, I had never been down there and didn’t feel comfortable poking around an area I didn’t know,” remembers Wills. “So I sent two of my friends–men–to determine if the place was safe. I’m not adventurous like that.” There would be no graveyard in the church, but Ethan stepped in to help in the search.

Ethan: “I offered to meet them in Tennessee and show them around. But in order to get to the church, you have to drive past the farm. That’s when I saw a white truck in the driveway, and I’m like, Whoa, somebody’s actually here. Mind you, in the years that I had been driving past the farm, I had never seen anyone there.”

Ethan got out of the car and introduced himself and launched straight into his story. “Look, I’ve been coming down to this area for a couple of years,” he told the man in the truck. “We have a strong belief that my family was enslaved here and, then later, that they sharecropped here.”

What Ethan did next took the man, named Jimmy, by surprise. He grabbed his scrapbook from the car and showed Jimmy the important information he had learned about Jimmy’s own family. “I said, ‘I know you’re a descendant of John Bertie Moore.’” According to Ethan, Jimmy was “blown away,” impressed by the information. “It was a good exchange, but we didn't trade any numbers. We just took a picture and said, ‘Nice meeting you.’”

Two years later, in November 2019, after several conversations and meetings between Ethan and the land-owning family, Wills stepped out of the car and saw the farm with her own eyes for the first time. The moment was surreal. “I saw the land as my ancestors had left it,” she remembers. “There were several organized cotton fields next to each other.” In the distance, she saw something different. “There were fields everywhere except for this one area that was a forest.” Within the first 60 minutes of meeting the host family, Wills and Ethan learned what in all likelihood lay beneath that patch of earth.

Part 5: On Hallowed Ground

As much as she’d longed to find her ancestors’ bones over the years, Wills was also afraid that all her digging would unearth more heartache. “There’s no extinguishing the hurt from when my father left us,” says Wills. “Now I see why he did it. My dad grew up under Jim Crow. I believe in personal responsibility, but when you have an entire nation blocking your progress, treating Black men, women and children ruthlessly, eventually all that pain turns to rage and you take it out on the people closest to you.”

On occasion, she’s felt an urge to scream from despair. But years ago, she turned to a spiritual practice to process years of emotional pain—the loss of her father, the chaos of her home life, the economic hardships—that included diaphragmatic breathing and self-affirming mantras. “I refuse to stay in the hurt. I talk to my pain, I tell it, ‘We are going to be okay. We are going to make it.’ I temper my pain with breaths. I think before I speak, and I find my way to feeling proud of myself and happy.”

By the time Wills stepped foot on the property in Tennessee where her family had been enslaved, she had spent years preparing for that moment. Her hosts would meet not just a famous, sophisticated New Yorker with an infectious gravelly laugh but one full of elegance and equanimity. Despite the fraught emotional dynamics of engaging with a family whose ancestors owned hers, the years of mindfulness and meditation helped her meet the moment with grace and composure.

The family greeted her with comparable warmth and kindness: “They prepared a marvelous lunch, cold-cut sandwiches, and really wanted to know me,” she says. “They had read my books and made an effort to make me feel welcome and comfortable.” Wills noticed herself relaxing into the easy exchange between them. “I realized how very much I liked them.” The feeling, it turned out, was mutual.

“When Cheryl stepped out of the car, I immediately knew I would like her,” says Anne, an elementary school teacher and a direct descendent of John Bertie Moore, founder of the plantation. (Anne’s last name, along with her family’s, is being withheld to protect the privacy and sanctity of the cemetery location.) “She was vivacious, eager, and enthusiastic. I loved her animated personality and could tell that she would be a lot of fun. She was happy to have arrived, and I was excited she was there.”

On this land, where unspeakable pain and hardship wreaked havoc on the lives of so many slaves, an unlikely friendship was taking root. “In a way, it doesn’t surprise me. Our families go back more than 200 years. They’ve been dealing with each other from the early 1800s. We have a history,” Ethan says. To add to the day’s importance, Ethan invited other distant cousins he had discovered to the farm. They were living descendants of Emma’s younger siblings. “We had descendants from four branches together that day. I remember saying to the group, ‘This is historic because our families, once again, are back together.’”

Anne: “Soon after their arrival, we went into our farmhouse and onto the back porch where we had lunch. Everyone was chatty and having a good time. I felt the atmosphere was relaxed and all [were] enjoying getting to know one another. Cheryl and her cousins, Ethan, Anne [Ankton], and Regina [Spears-Wilson], along with our family enjoyed getting to know one another over lunch before setting out for a tour of the farm. It was a memorable moment and a true highlight in my life.”

Wills also met Anne’s mother, Edith, the matriarch of the family—“a remarkable human being” Wills says— and Anne’s older brothers, Jimmy and John, who were good-natured, listened attentively, and asked questions. “[We got] to know more about them and their parallel tracks of tracing their family history,” Anne says. “It was amazing that they had all independently been tracing their ancestors and that each had found pieces to a puzzle that could be put together.” Jimmy agrees, adding, “This has been a remarkable story meeting Cheryl and her cousins and seeing how much effort that they have each put into researching their family lineage and how their independent findings have been able to create a detailed family history together.”

Soon, Anne and her family invited their guests to explore the property. They saw the original “old house” that John Bertie Moore had first built, now rickety and weathered by the elements. They walked across the empty fields where the cotton had been harvested. “I sighed deeply when I saw where I imagined my family working,” remembers Wills.

Then, Wills walked up a hill toward a forest, the only wooded area on acres of cotton fields. It was the site she had sought for years, the needle in the haystack: the cemetery. “I walked on it and closed my eyes to take in the moment,” she says. “It was an unmarked burial ground where I believe my ancestors, including Grandpa Sandy and Grandma Emma, had been buried.” Unbelievably, thanks in large part to Anne and her family, the area had been untouched and respected as hallowed ground for as long as they knew.

“Ever since I can remember, on Sunday afternoon before we put the equipment away and headed back home, we would take a family tractor ride around the farm to take in what had been accomplished over the weekend and to admire the beauty of the land,” Anne recalls. “We would drive our normal route alongside fields and through pecan trees. The ‘old house’ and cemeteries were always part of the tour.” Both cemeteries—one for the white descendants, the other for the African ones—were on the top of hills facing across from one another.

According to Anne, her father, an only child, passed down the family history both orally and through documents and records. And it was those same historical records that Wills would find in 2009. She had the matriarch, Edith, to thank for preserving and organizing them and later donating them to the Tennessee State Library and Archives. “Though we never used the word ‘slave’ or talked about the farm being a former plantation when we met,” says Wills, “ those papers opened everything for me. Along with her children, the matriarch, Edith, ensured that nothing was ever built over or near the gravesite after her husband’s passing.”

“My dad would be upset if the farmers plowed too close to the cemeteries and would put stakes around them to make sure that the planting did not encroach upon the area,” Anne recalls. “It was an understood truth that the cemeteries were never to be cultivated and were to be kept as hallowed land. To this day,” she emphasizes, “we continue to keep the cemeteries clean by picking up fallen branches and keeping them mowed. Each February the cemeteries are highlighted in yellow as daffodils bloom from the bulbs planted there by my parents through the years.”

The children, now adults working the land, have kept their promise. “We loved and respected my dad and the farm. It would never occur to us to do anything but keep the cemeteries as places of highest esteem. We did not know those buried there, but without a doubt, we wanted to honor them by preserving their place of burial.”

Wills stood on the land as a soft breeze gently brushed against her face and through her hair. She felt grateful to the family, but was unsettled, too. On the one hand, Wills recognized how lucky she was that the land had been continuously owned by the same family—a rarity—making it possible to locate her ancestors. On the other, she felt pained and sorrowful that her family’s bones were on the land where they had been enslaved. “All the men in my family were buried with military honor,” says Wills. “My grandfather and father are buried in Calverton National Cemetery in Long Island, New York, with honor, decency, and order. What gets me is that the ancestor that made both of their lives possible is likely buried under leaves and trees.”

The decision forming in her mind was a weight on her chest, but she had to say it: “I’ve come here to get the bones. You are good people, but I have to give my family a formal burial.”

To Wills’s surprise, Edith, supported by her daughter and sons, agreed to help. “We are glad that papers our family had kept over the years were able to be a piece of that puzzle,” says Jimmy. “We look forward to continuing to work with Cheryl and her family to honor the memories of their ancestors with dignity and respect.”

The unexpected news that they would gladly give her access to the land deeply moved Wills. It also, she knew, would make her next steps—finding a team to survey the cemetery, exhume the remains, and perform DNA testing to verify that these were, in fact, her ancestors—a little easier.

Soon after the visit, Edith and her children began clearing branches from the cemetery, preparing the land for excavation. Wills, back home in New York, began reaching out to archaeologists and other experts.

Together, the two families hope to address grave injustices from the nation’s past and finally honor a Civil War hero whose justice is long overdue. This was the first step.

Postscript: This story is the first in a series of articles about Cheryl Wills’s journey to address the generational impact of slavery and to honor her ancestors with proper burials. Look for the next installment in July 2022.

You Might Also Like