Can a Feminist Still Love Jack Kerouac?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

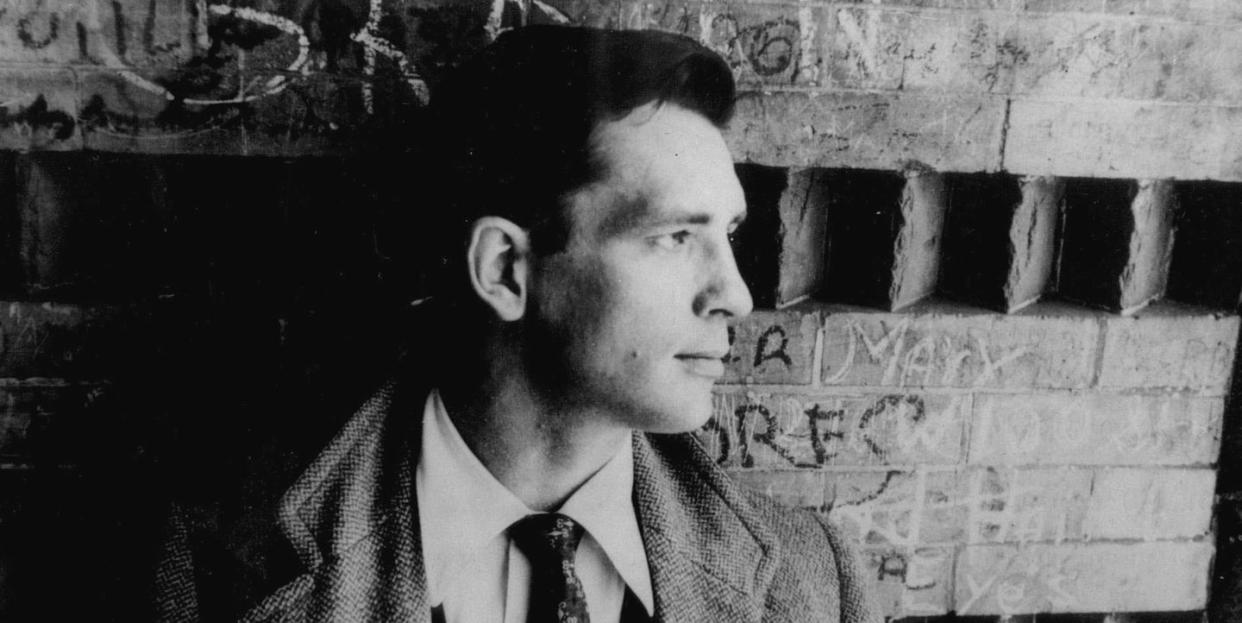

2022 marks the centenary of Jack Kerouac's birth. I was 16 when I read On the Road, and it changed my life. At the time, in 1973, abortion had just become legal and the pill widely available, but one-year-old Ms. Magazine was difficult to find in my North Carolina town. My hippie boyfriend hitchhiked home from Boulder, Colorado, and presented me with his battered paperback of Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel (along with Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen records). I’d never read anything that exhilarated me the way Kerouac’s prose did. The following year, I left town for college, did a bit of hitchhiking myself, and eventually landed in New York, where I became a writer and an editor. Kerouac—born 100 years ago on March 12—was four years dead when I devoured the book that “turned on a whole generation to a youthful subculture,” according to its back cover. The man who coined the term “Beat Generation”— and transformed San Francisco into countercultural ground zero—drank himself to death at 47. I learned this and more about the Lowell, Massachusetts-born son of struggling French Canadian immigrants from my 1973 reading list: Ann Charters’s riveting Kerouac: A Biography.

Charters was among that first generation of readers, writers, and musicians—including Thomas Pynchon, Sam Shepard, S.E. Hinton, Bob Dylan, and Janis Joplin, to name just a few—captivated by Kerouac’s cry that “the road is life” and inspired by his “spontaneous bop prosody.” (While researching my 2019 biography of Joplin, I learned that reading Kerouac at age 14, in 1957, precipitated the singer’s journey out of conservative Port Arthur, Texas.) In 1998, as editor of Rolling Stone’s book division and still curious about the Beat scene, I conceived The Rolling Stone Book of the Beats. I commissioned essays from Charters and women writers who’d personally known Kerouac: Joyce Johnson, Hettie Jones, and Carolyn Cassady, among them. Johnson, the author of Minor Characters (detailing her relationship with Kerouac from 1957-58), wrote in “Beat Queens: Women in Flux,” “The Beats have often been accused of having no respect for creative women. But in truth the lack of respect was so pervasive in American culture in the postwar years that women did not even question it.” An accomplished novelist and memoirist, Joyce would later write the illuminating The Voice Is All: The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac. For my Book of the Beats, her essay contended that she “found an unexpected source of encouragement [from Kerouac] when I showed him the novel I was working on.” Upon reading On the Road in 1957, she counted herself among “thousands of Fifties women [who] experienced a powerful response to what they read. On the Road was prophecy, bringing the news of the oncoming, unstoppable sexual revolution—the revolution that would precede and ultimately pave the way for women’s liberation...It suggested that you could choose to be unconventional, choose to experiment, choose to open yourself up to a broad range of experience.”

Four decades after my first encounter with On the Road, I’m writing a biography of Kerouac, and I’m grappling with his depictions of women and people of color. When I first read his words as a teenager, I was so transfixed by his “promise of every cobbled alley,” it didn’t even occur to me that the richly textured characters in OTR are all male. Or that Kerouac’s empathy for and identification with marginalized people could be offensive to those very people. I identified with protagonist Sal Paradise, an aspiring writer caught up in adventures on the road with the speeding bullet named Dean Moriarty (inspired by Kerouac’s friend and muse Neal Cassady). Today, I recognize the women in the book are mostly one-dimensional objects of the male gaze, either users themselves or to be used by the frenetic adventuring men. But as Joyce Johnson did in 1957, I craved the freedom offered by that emblematic road so mightily, I didn’t look outside my own perspective, that of a privileged white girl in a Southern town where nonconformity was still shunned.

Fellow music journalist and author Amanda Petrusich also reexamined her entanglement with On the Road in a 2018 New Yorker essay, “A Slightly Embarrassing Love for Jack Kerouac.” I compared notes with her and reached out to other women who fell under Kerouac’s spell earlier in their lives.

Discovering the book as “a brooding and sullen high-school freshman,” Petrusich reflects today that “it seemed like the key to something. I think it’s common at that age to be drawn to anything that promises or articulates freedom or ecstasy. I was old enough to want those things, but too young to have them, so instead I lived through books like On the Road. I didn’t relate to the women in the book at all, in part because they’re hardly women— they’re sketches, in a way. They never felt truly real or three-dimensional to me. But I can’t honestly say that bothered me at the time. It bothered me later. I wish I had been a more enlightened teenager, but that sort of reading didn’t happen for me until I was in my late twenties and a little more awake to the way the world bends for white men.”

Kerouac’s work would impact her own career path: “His writing was extraordinarily musical, and it certainly shaped the way I think about the rhythm of language, the way a sentence can move,” Petrusich affirms. “In that way he was hugely influential for me. He understood that writing could groove. Kerouac is such a beautiful writer, and his life and work hold an undeniable romance, and he meant something to me at a moment in my life in which I was really hungry for someone to show me how to live outside of certain cultural expectations—how to be an artist, how to be a weirdo, how to wander, how to want.”

Writer and adventurer Melissa Holbrook Pierson, author of The Perfect Vehicle: What It Is About Motorcycles, first read OTR at 19, “and immediately decided I wanted to be a Beat,” she says. “I read On the Road in the same kind of trance in which it was said to have been written, and I wanted that almost frenetic energy in my own writing. I also swooned at the poetic concision of his prose, as well as his intelligence. God, how he could condense massively complex observations into a single sentence!” Kerouac’s subject matter also made an impact on Pierson, the author of The Place You Love Is Gone. “The notion that the real America resides in seedy, careworn, hidden, unheralded people and places—I think that seeped directly into the heart of our generation. A lot of us, especially in the 1980s, thought there was no way to truly know America unless we hit the backroads. Tasting various regions’ different flavors—when they still had them—required us to light out in search of the ‘original’ and ‘authentic.’ I think it was largely Kerouac who instilled the idea in us—suspect the sanctioned; respect the unauthorized.”

Pierson’s views on Kerouac’s representation of women have changed over the years, she says. “When I was young, I responded to the book as a metaphorical journey, and to its heroic voice. I grew up steeped in second-wave feminism, which I professed, but I had actually internalized cultural misogyny to the point that I held this inchoate idea that the best art was men’s. I almost exclusively read men’s work and aspired to their ‘genius.’ Fast forward thirty years to 2021, and I come across the Penguin edition of On the Road—with the eye-opening introduction by Ann Charters—on the giveaway table at my local dump. I’m prone to taking things like this as a sign: it was high time for a reread. And it was suddenly rocky going. The ravenous appetite for experience depicted in the book included the uncaring consumption of women, along with racist tropes. So much of the valorized writing of previous eras contains ideas like these. It’s necessary to reckon with this fact without putting everything written before 1990 in the trash. I think any seminal work, one that represents a major cultural pivot, is not only worth reading, though, but necessary to read. ‘Necessary’ doesn’t make it relevant; I think of it as an historical artifact.”

Journalist Sheila Weller, bestselling author of Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon and the Journey of a Generation, among other books, discovered Kerouac in the early 1960s. “I was a Kerouac fan! I had a bit of a crush on him,” she recalls. “I loved On the Road. His vibe—passionate but vulnerable, bad-boy searcher—all of it was very compelling. His treatment of women? Not good! And his friends’ was worse. (Burroughs? Hello…) But such was the norm in Hipville in those days. Today, it is hard for a feminist to like Kerouac. But—through On the Road—we can enjoy his writing, his passion, and his brio and measure how much we have grown.”

Actor and writer Amber Tamblyn was dazzled by aspects of the Beats at a young age. But as a founder of #MeToo and the author of Era of Ignition: Coming of Age in a Time of Rage and Revolution, she’s had a change of heart. “I grew up around artists, writers, and musicians from the Beat Generation because my parents are artists who knew many of them,” says Tamblyn. “Most writers and people I knew in Southern California thought of Kerouac as one of the cool poets, a writer on the edge, both in his work and how he lived. I didn’t really look up to his style of writing as much as I looked up to what he represented. He lived a wild life, equal parts destructive and deeply curious, respected and lauded for everything he was, including the worst parts of himself. It wasn’t until I got older and became more aware of what my own feminist desires looked like that I realized, as a woman, any admiration I had for Kerouac was through a longing to be as free as he was, to be as selfish and renowned as he was allowed to be—as all of them were allowed to be—without consequence. Most especially during the #MeToo movement, it was increasingly hard to separate the Ginsbergs and Kerouacs from aspects of who they personally were. Their success stories were predicated on predatory behavior that fed into a cycle of abuse: They got away with what they did because they were famous artists who were part of a cultural revolution, and the more they got away with it, the more famous their revolution became. The stars of the Beat Generation were white men and white men alone. I can appreciate Kerouac’s place in history and what his writing has meant to so many people the world over, but for me personally, I do not hold him among the greats of his generation and that time—writers such as Jack Hirschman, Diane Di Prima, and Amiri Baraka. For Kerouac, the personal was not political because it didn’t need to be. He didn’t need to write out of a place of survival, out of an urgency to expose the injustices around him, of which there were plenty. That’s fine, but as a woman who does not have the luxury to do the same, I’ll take a writer who writes to save lives any day over a writer and his road.”

Writer and academic Laina Dawes, author of What Are You Doing Here? A Black Woman’s Life and Liberation in Heavy Metal, has also moved away from an initial interest in Kerouac. “I discovered On the Road in my early 20s during the grunge era,” she says. “I was probably inspired through other authors I was interested in, as I also read Burroughs, Ginsberg, Hunter Thompson, and my favorite, Hubert Selby, Jr. I had tagged along on one of my father’s business trips to San Francisco, so I begged him to come with me to the City Lights bookstore and I purchased On the Road there.” She liked Kerouac’s “freedom, his traveling, and how he wrote about his observations,” she says. “I wanted to be a writer who could have those experiences. I felt that it was really the only way to be a writer, to travel and see as much as you can to improve your prose. In hindsight, the book screamed of ‘white privilege.’ I quickly gleaned that as a Black woman, I would never feel comfortable doing what he did and probably would encounter a lot of horrible things along the way, as Kerouac’s whiteness really protected him a lot and his attitude made him feel superior. Despite the impoverished career as a writer, he never seemed to lose his arrogance. I think his depictions of women and POCs reflected the time the book was written in. But I was semi-dejected that there was a sense of freedom within that book that I felt was only for white men to truly experience.” She feels On the Road should be read by journalism students to “critique, specifically the gender/ethnicity concerns. It is a great example of a certain style of writing and definitely relevant in chronicling that civil rights/counterculture generation. But it should be positioned as a study, and not a book you should shape your life around.”

Fiona Paton, associate professor of English at the State University of New York at New Paltz, has been teaching classes on Kerouac and the Beats for decades. A native of Scotland, her discovery as a teen of Kerouac’s experimental writing in his book Dr. Sax led her to graduate school in the States, where she earned a PhD at Penn State, writing her dissertation on Kerouac. “When I teach Kerouac, I also share with my students some writing from a similar time period,” she says, “like Henry Miller, Hemingway, Philip Roth, or Norman Mailer. I show them the extent of the chauvinism considered to be normal at that time. My students have grown up in a very different ideological world. When I first discovered Kerouac, I didn’t notice the bias, and that was in part because we were just used to reading books by men that privileged the male perspective. We just accepted it as normal, which our students now don’t. Which is good. But compared to many male authors of that time period, Kerouac is actually a bit more progressive and enlightened. He is capable of insightful social observation in works that people don’t read so much, like Visions of Cody. You don’t always see it in On the Road, but I also teach The Subterraneans, and confession is really important to Kerouac’s ethos as a writer.”

In that 1958 book, “the story of an unself-confident man, at the same time of an egomaniac,” in Kerouac’s words, his protagonist falls in love with a Black woman, Mardou Fox.

Kerouac “lays out all of his own prejudices against women and people of color,” says Paton, “but he confesses them and says, ‘Yeah, I’m an asshole.’ I find there to be a redemptive quality in Kerouac, that he can do that kind of self-critique. It’s really important that students understand him as working through a culture that is all about white privilege. He critiques contemporary popular culture of his time, and it connects to the formation of bias and prejudice. Yes, there’s a romanticizing of the Other, but it’s also quite new and different for a white person to say, ‘I don’t want to be white anymore’ when American identity was very much defined in terms of the white male. People forget that his perspective then had a radical edge to it, that goes beyond just naive romanticism.”

Among numerous performers influenced by Kerouac are singer-songwriters Michelle Shocked, Mary Gauthier, and Debra Devi, who each discovered On the Road in their teens and left home. Texan Michelle Shocked, whose 1988 single “Anchorage” was inspired by a letter from a friend—just as Kerouac’s work was sometimes based on his correspondence with Cassady—did her share of hitchhiking. “I read the book when I was 16,” she recounts, “so it became my gateway to adventure. When you read Kerouac, by the time you put the book down, you are thinking like him or you’re thinking that you’re thinking like him. There is a beatific glow. But this would be a very different story if it had been told by a woman. When you go and live that life, the story includes the experience of being raped. Sorry, I’m bringing up an unpleasant truth here, but male privilege has its privileges. If that’s what a feminist’s deconstruction of On the Road looks like, imagine what it looks like to an audience of African Americans.”

Mary Gauthier’s introduction to On the Road coalesced with her coming out as a teenager. “It was probably around 1979-1980, when I was 17,” she recounts. “I’d quit high school, run away from home, moved in with fellow runaways in Baton Rouge, and started hanging out in the gay clubs. I met a bisexual music-loving guy in the club one night, we became fast friends, and I moved in with him. He was a huge fan of Patti Smith and Jim Morrison, and from there, all roads led to Kerouac. I read On the Road, carried it around as a totem as I moved from place to place. Kerouac’s other books led me to Rimbaud, Nietzsche, William Blake, Kafka, Baudelaire, William Burroughs.”

The Grammy-nominated artist lived a frantic life until she got sober in her late 20s and became a critically acclaimed songwriter at 35. “The impact of Kerouac’s writing on my work is more about spirit than style,” Gauthier says. “His understanding of freedom as a rejection of a mundane life helped shape my own definition of the word. The fire, the burning, the pushback against conformity, pushing back against the death grip of a life not of my own making. Embracing spontaneity, honoring the deep longing inside me…that’s the lasting impact. Also, I believe that there are books that burn in your soul when you are a teenager, whose impact lasts a lifetime. On the Road is one of those books for me. That said, now that I am older, I can better see the sexism, homophobia, and racism in his writing, too. Also, I’ve rejected the destructive, downward pull of addiction, the romance with oblivion associated with Kerouac. These are the forces that killed the man at the young age of 47, yet there is magic in Kerouac’s male hero’s adventures that I still relate to, and probably always will.”

After Debra Devi discovered On the Road at 17, it set her on a path to become a blues-rock guitarist. “I recall feeling both thrilled and disheartened,” she says. “Thrilled by the wild, bubbling, relentless nonstop speed prose and the adventurous road trip. Yet disheartened because the freedom the male characters reveled in—like my secret dream of playing guitar in a rock band—was so clearly not for me, a girl. But at 18, my teenage rebellion finally kicked in, sparked by The Subterraneans, which got me dreaming of moving from Wisconsin to Greenwich Village. In a pawnshop, I bought the electric guitar I’d been craving since my early teens. By that time, I’d decided women could go ‘on the road,’ too. I moved to New York, joined a band, and did just that—touring all over the U.S., Canada, and Europe.”

The author of The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu, Devi says her “appreciation of Kerouac’s immense gifts as a writer has only grown over the years, re-astonishing me whenever I revisit his work. Yet I always found his machismo tiresome, and today also feel sad that he lived and wrote during a time when homosexuality was widely closeted and criminalized. Like Henry Miller, Kerouac often wrote about women as less-than-human, to be used for male pleasure. Regarding people of color, Kerouac indulged in a pretty embarrassing romanticizing of his Black and Latino characters, laying on them all kinds of magical/sexual/artistic ‘otherness’ that has not aged well.” But Devi still recognizes the value in his work: “Kerouac’s breakthrough for all artists, in my opinion, was his brave willingness to numb his inner censor and just write, as freely and wildly as he could. Every time I play a guitar solo or sing a song, I know I have to do the same thing. I have to turn off the inner censor, get into the divine slipstream, and flow with it. Kerouac’s best moments are a glistening snail’s trail of that magical experience, and an inspiration.”

Gauthier, the author of 2021’s Saved by a Song: The Art and Healing Power of Songwriting, agrees that the power of Kerouac’s work persists. “On the Road is an inspiration for anyone who feels dissatisfied with the pressures to conform to a conventional lifestyle that is not authentic to them,” she says. “I imagine the book burners will set flame to it again at some point when it’s assigned in a classroom somewhere, a sure sign that the book remains impactful and expansive on the minds of young readers.”

So how do we as feminists approach Kerouac’s work? Clearly, in our artistic lives, many of us, regardless of gender, have been emboldened by his writing. As we understand his flaws, his work still stands as transformational—though the man himself never achieved his own aspirations as a human being. This conversation will continue.

Holly George-Warren is the award-winning author of 16 books, including the bestseller Janis: Her Life and Music, and a longtime contributor to such publications as Rolling Stone, The New York Times, and Entertainment Weekly. She has received two Grammy nominations: for coproducing the box set Respect: A Century of Women in Music, and for her liner notes to Joplin’s The Pearl Sessions. She is currently writing a biography of Jack Kerouac (Viking) and collaborating on a book with Dolly Parton (Penguin).

You Might Also Like