How “Fellow Travelers” Fit Decades of Queer History Into 75 Seconds

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

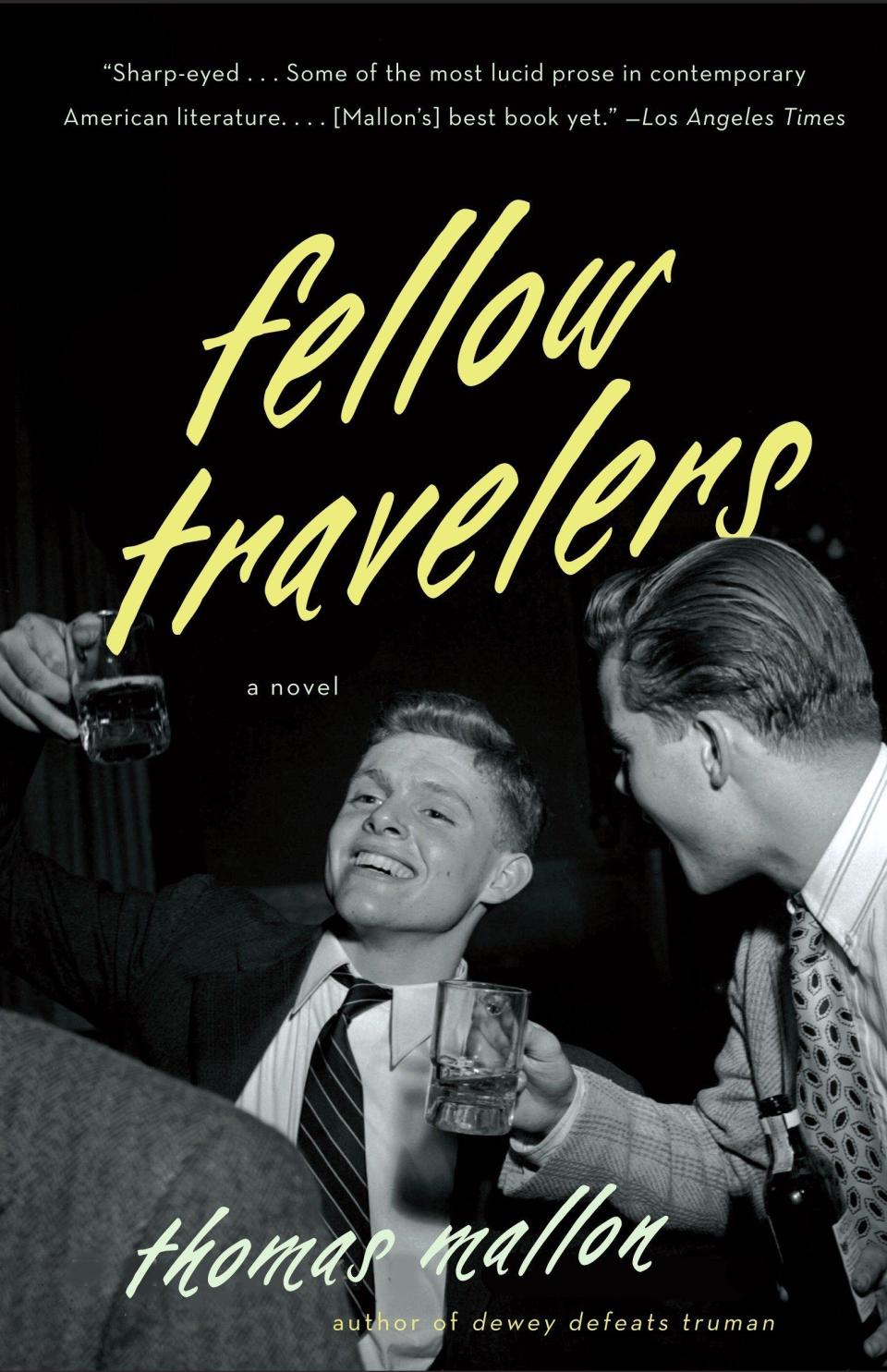

Ron Nyswaner, the creator of the Showtime miniseries Fellow Travelers, says the characters at its center have been living with him ever since he read author Thomas Mallon's 2007 novel of the same name. Mallon, a prolific writer and critic, is known for his extensively-researched and minutely-detailed works of historical fiction, and Fellow Travelers was no exception. It follows two men, Hawkins "Hawk" Fuller and Tim Laughlin (played in the show by Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey), who meet and fall in love in the Washington, D.C. scene just as McCarthyism descended on the city. The story of their tumultuous romance and the people it draws into its orbit spans decades of queer history, from the 1950s through the 1980s AIDS crisis. When he finally began adapting Hawk and Tim's story, Nyswaner was presented with the challenge of condensing those decades of history, told through a 368-page novel, into eight episodes of television.

Fellow Travelers

amazon.com

$13.52

But nested within that challenge was another, less often discussed part of creating a TV series: putting together an opening title sequence that introduces the themes and tone and visual language of a show to the viewer in just a minute or two. When done right, these opening credits can say a lot about the series they herald. The opening of The Crown shows an actual crown being meticulously forged from metal and gemstones; Game of Thrones gave viewers a literal lay of the land, swooping over a map of Westeros as the credits rolled. If telling 30 years of queer history in under eight hours was a game of artful storytelling and editing, creating the opening credits was a side quest, a speed run. "It's 75 seconds that occupied four months of my life," says Nyswaner.

Early on, Nyswaner, along with director and executive producer Dan Minahan, thought about the concept of redaction. The series opens amid the Lavender Scare, an offshoot of the Red Scare in which gay workers in the government and military—who were already living double lives and hiding their sexualities—became targets for McCarthy's moral panic. People lost their careers, their livelihoods, their social networks, and worse. Coworkers were encouraged to rat each other out. Men could come under risk of firing and humiliation for seeming effete to their officemates; women could be dismissed for rejecting the wrong man's advances or even not wearing enough makeup. All of this was considered acceptable evidence of their "deviant" sexuality.

Nyswaner and Minahan imagined photos of queer people being redacted by the same bold, black lines that would mark up a classified document. The obscured imagery evokes an era in which gay men and women—and non-binary and trans people, before such words existed—were pushed further into the darkness. But then, those redactions are erased as the opening credits continue, revealing scenes of what Nyswaner calls "gay sexuality and liberation," reflecting a joy that was always part of the story, even if it was hidden away and guarded. "It grew naturally from that idea of covering and uncovering," he says. "Which is what our show is about."

As they began to conceptualize their vision, Minahan started saving images into his phone here and there. "Eventually, I had one of those little photo slideshows that iPhone makes you, and I set it to a work of countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo and Philip Glass. We all kind of fell in love with it," he says. "Then of course we brought in the really skilled people to create the real thing." (Those people being Toronto-based video production company IAMSTATIC and the show's own composer Paul Leonard-Morgan.)

Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love 1850s-1950s

amazon.com

$38.99

As with Mallon's novels, Nyswaner's adaptation focuses on verisimilitude. The production hired a researcher, Louis Gropman. Quotes that real-life characters like McCarthy, Roy Cohn, and David Schine gave on the public record are relayed verbatim on-screen. So he and Minahan began hunting for contemporaneous photos and footage of real queer couples. "It was essential," says Nyswaner. "Because it lends the show authenticity. These are real people whose lives we're making historical fiction about. To see that at the beginning of the episodes reminds you that this isn't a story that someone has entirely imagined. The show isn't asking, 'What if life was like this?' The show is saying, 'This is what life was like.'"

As they began sourcing images and footage, they found "many queer collaborators," says Nyswaner. Some photos came from Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love, 1850s-1950s, a collection of photos of queer couples curated by Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell, themselves a gay couple.

Minahan found a 1954 film called Nus masculins by queer, experimental, French filmmaker François Reichenbach on YouTube and set out to find out who now owned it. Once he tracked down Reichenbach's cousin in France, Nyswaner wrote her an impassioned note, and she said her cousin would have been honored. The film lent the opening some of Nyswaner's favorite footage. "There's something so innocent about it," he says. "The boys jumping into the ocean have an exuberant kind of undefined sexuality, which I think is really beautiful." (Not as innocent were clips from the famous 1972 gay porno Bijou.)

And while Fellow Travelers explore the experiences of Black and non-White queer characters, Nyswaner learned that photos of gay Black couples were "not as plentiful as photographs of white people of white couples," he says. "That was something we had to look hard for." The double stigmas of racism and homophobia may have made it even harder for gay Black people to feel safe committing themselves to a physical photograph of themselves living openly with a gay friend or lover. But Nyswaner made sure to seek out and include such images.

And for a select few images he wasn't able to get the rights to, Nyswaner had them recreated with the help of friends as models. One, a close-up to two men kissing, became an essential centerpiece of the sequence—the actual title card over which the words Fellow Travelers first appear—emphasizing a kind of in-your-face boldness that can come with simply being seen.

The other bold centerpiece? When Nyswaner's "Created by" credit appears superimposed right on top of a man's crotch. "That," he says laughing, "Was a personal request."

You Might Also Like