FDA Approves New Drug to Treat Alopecia in Adolescents and Teens

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

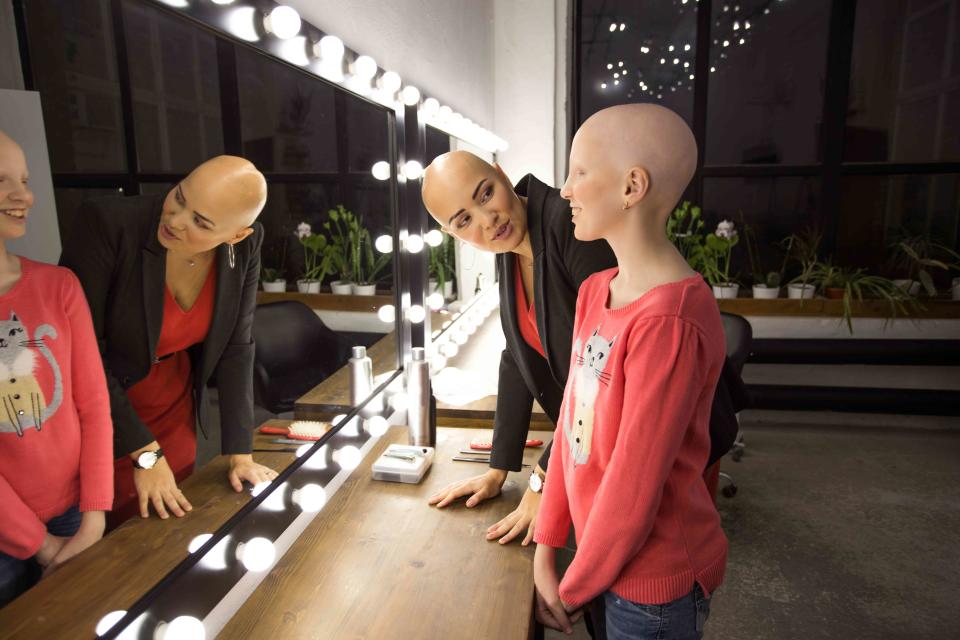

New treatment can give young people with alopecia a sense of normalcy and renewed confidence.

Sasha Shtepo / Getty Images

Medically reviewed by Rachel Nazarian, MD, FAAD

Maria Strattner, now 18, loved braiding her hair in middle school. At 13, she’d often part her hair in two and string it into Dutch braids as her go-to style. But while doing so one day, she noticed a few quarter-sized spots of missing hair on her scalp.

“I was like, that's kind of weird,” Strattner says. “And then, like a week later, I had no hair.”

Strattner was diagnosed shortly after with alopecia areata, an autoimmune disease that causes hair loss throughout the body.

“It's commonly called or referred to as alopecia, but alopecia just means hair loss,” explains Brett King, MD, Ph.D., an associate professor of dermatology at Yale School of Medicine. “Alopecia areata is a specific form of hair loss, and happens to be the second most common form of hair loss after androgenetic alopecia, which is also called natural pattern or female pattern hair loss.”

Alopecia areata affects about 2% of the population, Dr. King says. About 500,000 to 1 million of those people have severe enough cases that warrant the use of medication. But getting access to treatment for alopecia areata has historically been hard to come by, especially for young people.

But now there is a new treatment giving hope to those over the age of 12 with severe alopecia areata. In June 2023, the Food and Drug Administration approved Pfizer's medication Litfulo. It's the first and only approved treatment for adolescents. And as we're hearing from both Strattner and another young woman who took part in the clinical trial, it's been life-changing.

Related: Hair-Shaming Is a Thing—Here’s Why We Need to Stop Judging Parents When It Comes to Their Kid’s Hair

Coping Through School With Alopecia

Middle school is hard enough. Most kids are experiencing puberty or general teenage angst, and are stuck in between a childlike version of themselves and a more mature, grown-up young adult. So developing a disease that drastically changes your external features can add to a host of other troubles.

“It was awful, I'm not gonna lie like middle school is already rough and I was fortunate that I was having a pretty good time up until [my diagnosis],” Strattner recalls. “My experience wasn't like absolutely the worst that it could have been, but definitely middle school was not a great time for that to hit.”

Brittany Craiglow, M.D., is an associate professor adjunct in dermatology at the Yale School of Medicine who specifically treats children and adolescents with alopecia areata. She says it may be easy to scoff at the idea of devastation over hair loss, something that seems so trivial in the face of overall health. But hair is something so connected to our identities, and when it's suddenly gone, it can be a painful experience, especially for adolescents.

“As an adolescent, you kind of just want to be like a friend, you want to be able to go to the movies or play soccer, or whatever and just kind of be yourself and not have to try to hide your hair loss or explain your hair loss or have people staring at you or telling you they're praying for you because they think you have cancer,” Dr. Craiglow explains. “You just kind of get all this unwanted attention when you have alopecia areata, and I think that’s hard for everybody, but it's especially hard during those years.”

When Gracie, who only wanted to be identified by her first name, was diagnosed with alopecia areata at age 11, the emotional toll of her hair loss was felt by the rest of her family, too.

“The thought of your child never having hair again, it's very emotional,” Gracie’s mom, Crystal, says. “You brush your daughter's hair growing up and right before we shaved her head, I put a little locket of her hair in a ponytail because I thought—it even makes me cry thinking about it now—but this is the last time I'll ever see her with hair.”

"The thought of your child never having hair again, it's very emotional."

Crystal, mother of a child with alopecia areata

Treating Alopecia Areata

In the past, both Dr. Craiglow and Dr. King often had trouble treating their patients with alopecia areata because they’d prescribe a class of drugs called JAK inhibitors that are used for other conditions, like rheumatoid arthritis or ulcerative colitis. This off-label usage of those drugs for alopecia areata often meant trouble with insurance companies.

“If you're holding the purse strings and medicines are expensive, what do you say as an insurance company? You say no,” Dr. King explains.

That gray area of the available treatments meant a lot of people in need were left without options, especially young patients like those of Dr. Craiglow. Strattner’s doctor suggested she try injections, a common tactic used to regrow hair in alopecia areata patients. Ultimately the extent of her hair loss was too severe to attempt, so she started looking for other routes after getting almost no results from the steroids she was prescribed.

That’s when Strattner found a clinical trial for a new alopecia areata drug while doing research for a school project. Strattner and her family were introduced to Dr. King, who was leading a study on the effectiveness of new medication to specifically treat alopecia areata called Litfulo.

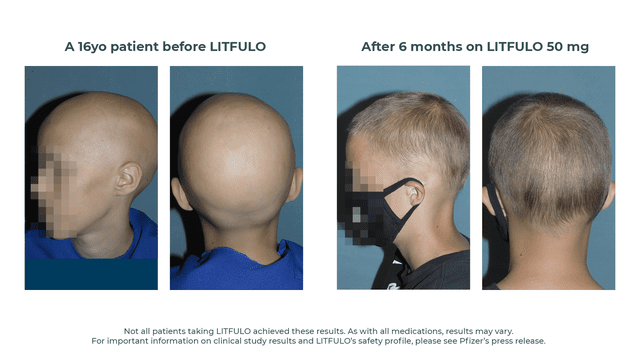

The once-a-day pill was tested in more than 700 people, around 100 of whom were adolescents. Everyone in the study had significant hair loss and took the medication for at least 24 weeks, and what the researchers found was pretty incredible.

“What we're observing, or what we look to observe over the course of those first 24 weeks is how many of everybody who starts gets to 20% or less scalp hair loss,” Dr. King explains. “At week 24, it was 23% of people achieved this dramatic scalp hair regrowth, and over another 24 weeks, so out to 48 weeks, almost one year of treatment, that number rose to 40% of people achieving this low amount of scalp hair loss or complete scalp hair regrowth."

Gracie's mom Crystal also found the Litfulo trial after Gracie was prescribed a topical cream that wasn’t producing any results. Just after her 12th birthday, Gracie enrolled in the trial. She and her mom believe she was initially given a placebo for the first six months and then given the actual drug, at which point her hair started growing back significantly.

“I mean a few weeks after I started getting the medication is when we saw hair regrowth and once my hair started growing, it was really rapid,” Gracie recalls.

Strattner was another one of the study participants who had positive results from the use of the drug. “To put it in perspective, I looked through my camera roll, I had no hair in 2019, I believe was the end of it,” Strattner says. “And then I had pretty much a full head of hair by like November 2020. So that's kind of like a year I guess.”

Pfizer

16-year-old before and after using LitfuloThe Future of Alopecia Areata Treatment

The FDA's approval of Litfulo to treat adolescents with alopecia areata was based on the results of Dr. King’s study. “With FDA approval, it means access expands dramatically,” says Dr. King. “It was hard for people to get treatment. And now with these approvals, it's truly paving the way for this to be a common thing to do, as opposed to a rare thing for a dermatologist to do.”

As with any drug, there is a risk of side effects, as Dr. King explains. Being a JAK inhibitor, the potential side effects of Litfulo are listed as cardiovascular disease or blood clots, among others. But both Dr. Craiglow and Dr. King say these side effects are typically found in patients who are using the medication to treat other conditions and they were not found in patients utilizing the drug to treat alopecia areata.

For Dr. Craiglow, whose patients were also a part of the clinical trial, the approval of the medication means hope for even more options for the younger population with alopecia areata.

“This was huge in the first approval of the adolescent population. [Other medications] will be studied in adolescents and hopefully, eventually these drugs will also be studied in younger children under 12, who, for them, we still don't have an approved treatment option,” Dr. Craiglow says. “I think now that there's kind of traction with the pharmaceutical companies recognizing all of this disease study, inevitably, it's just gonna get better and better.”

Most of all, the drug’s approval has given so many young people with alopecia areata a sense of normalcy back.

“It's definitely easier just living everyday life,” Gracie says. “And being able to go to sleepovers without worrying about having to wear a wig or put on my eyebrows or being hot and playing volleyball wearing a wig. Just everyday life, doing things that you do when you’re 12, 13, or 14 years old. It’s been a lot easier and I definitely have gotten confidence back with my hair growing back.”

Related: Can Birth Control Cause Hair Loss?

For more Parents news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Parents.