Fashion Production’s Climate Crisis in 4 Graphs

As 2023’s COP28 parley fades into the rear view, we share in four graphs the key findings from our “Higher Ground?” reports published in September. The work measures the present and future risks of exposure to extreme heat and flooding in some of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries for apparel workers, suppliers, fashion brands and investors.

Today, fashion focuses its climate change efforts on goals such as increasing use of recycled fabrics, reducing water usage, and cutting down its notable greenhouse gas emissions—fashion ranks third on greenhouse gases behind only global food production and construction.

More from Sourcing Journal

But these mitigation efforts by the fashion industry largely ignore the knock-on implications of climate breakdown on the workers, communities and industries producing the world’s garments. This is the problem of adaptation, and it is not part of fashion’s plan.

In our analyses we aim, first, to understand the industry’s exposure to climate risks and the costs of climate adaptation for workers, manufacturers, buyers and investors and governments. Second, we aim to inspire industry actors to formulate adaptation strategies that are large-scale and fit for purpose. We want to see these new measures and costs written into the business plans of the industry, into collective agreements, and into budgets and objectives of regulators.

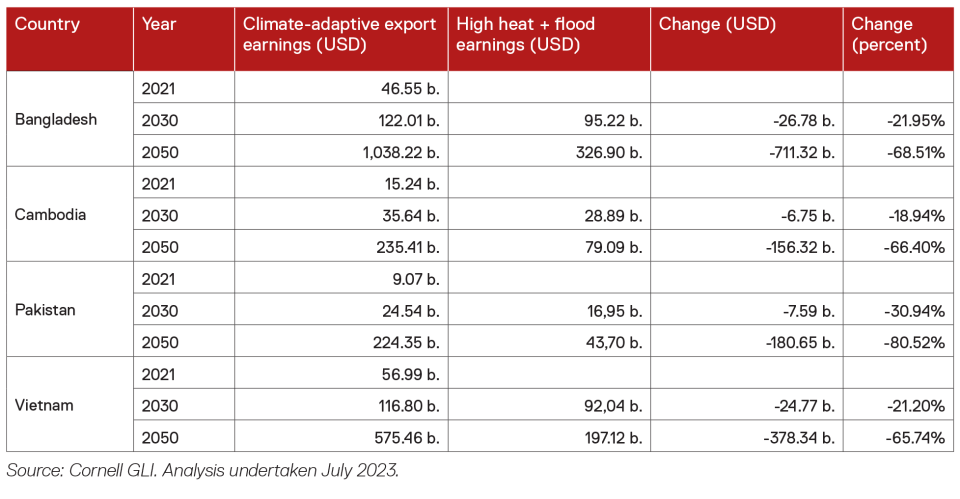

We calculate that without urgent adaptation measures that cool buildings and people, divert flood waters, the combined apparel export earnings of four key producing countries—Bangladesh, Cambodia, Pakistan and Vietnam—will come up 22 percent short by 2030 and 68 percent by 2050. These economies will forego nearly 1 million new apparel jobs by 2030 and 8.6 million jobs by 2050. Our analysis of leading global sportswear brands shows that extreme heat and flooding in Cambodia and Vietnam could consume 5 percent of net operating profits after tax per year.

A 5 percent falloff in profits is what brands and investors alike would regard as a material risk. So why are fashion firms not investing in climate adaptation? Fashion’s business model sees these effects for workers and manufacturers as externalities. In short, they’re someone else’s problem.

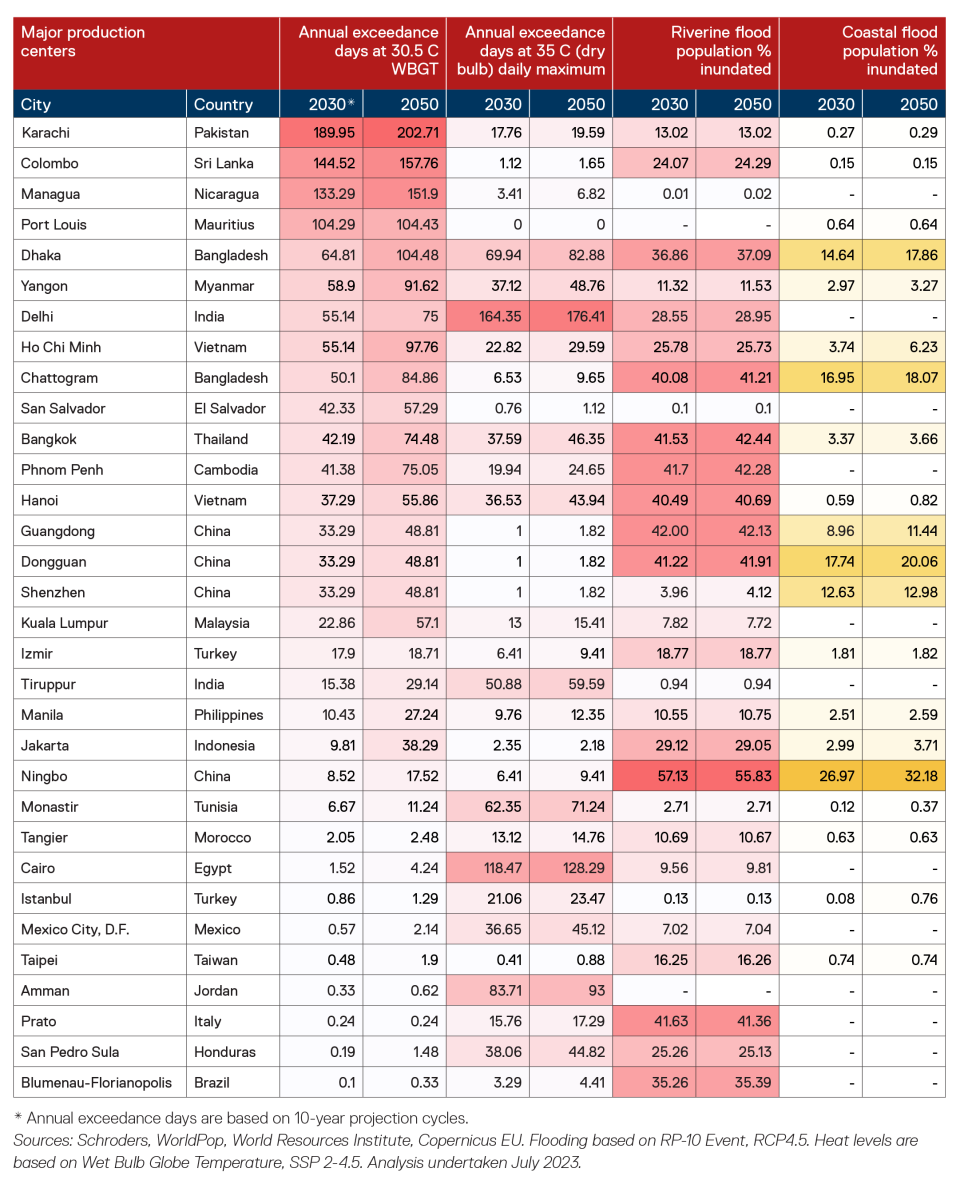

Our work examined the fashion industry’s exposure to physical climate risk illustrates changes in exposure to four key physical risk measures in 32 apparel and footwear production centers in 2030 and 2050. We represent relative heat stress levels using the number of days per year for which the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) readings reach above 30.5°C – i.e. “exceedance days.” This is the threshold above at which an hour of light-to-moderate work should be equal parts effort and rest. Our flooding projections include both coastal or tidal and “storm surge” flooding, and a combination of river flooding with rainfall flooding. The indicators of flood vulnerability are the percentages of each center’s populations that will be inundated—most of them at less than 0.5 meter—in a 10-year flood.

Several production centers stand out for their vulnerability to high heat, humidity and flooding: Colombo, Dhaka and Chattogram (Chittagong), Yangon, Delhi, Bangkok, Phnom Penh and the massive Dongguan-Guangdong-Shenzhen region.

Many of these centers are tropical and sub-tropical hot spots. Are these projected exposures to extreme heat and humidity much higher than recent levels? We compared 2004–2014 WBGT using the same climate models to our 2030 exceedance days estimates. Among cities in our focus countries—Karachi, Dhaka, Ho Chi Minh City and Phnom Penh—the average number of 30.5°C WBGT exceedance days climbs 50.9 percent from 39 days in 2014 to 59 by 2030. Starting from relatively low levels, exceedance days more than double by 2030 in Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi and Phnom Penh. Starting from relatively higher levels, Dhaka’s exceedance days will be 63 percent higher and Karachi’s 20 percent.

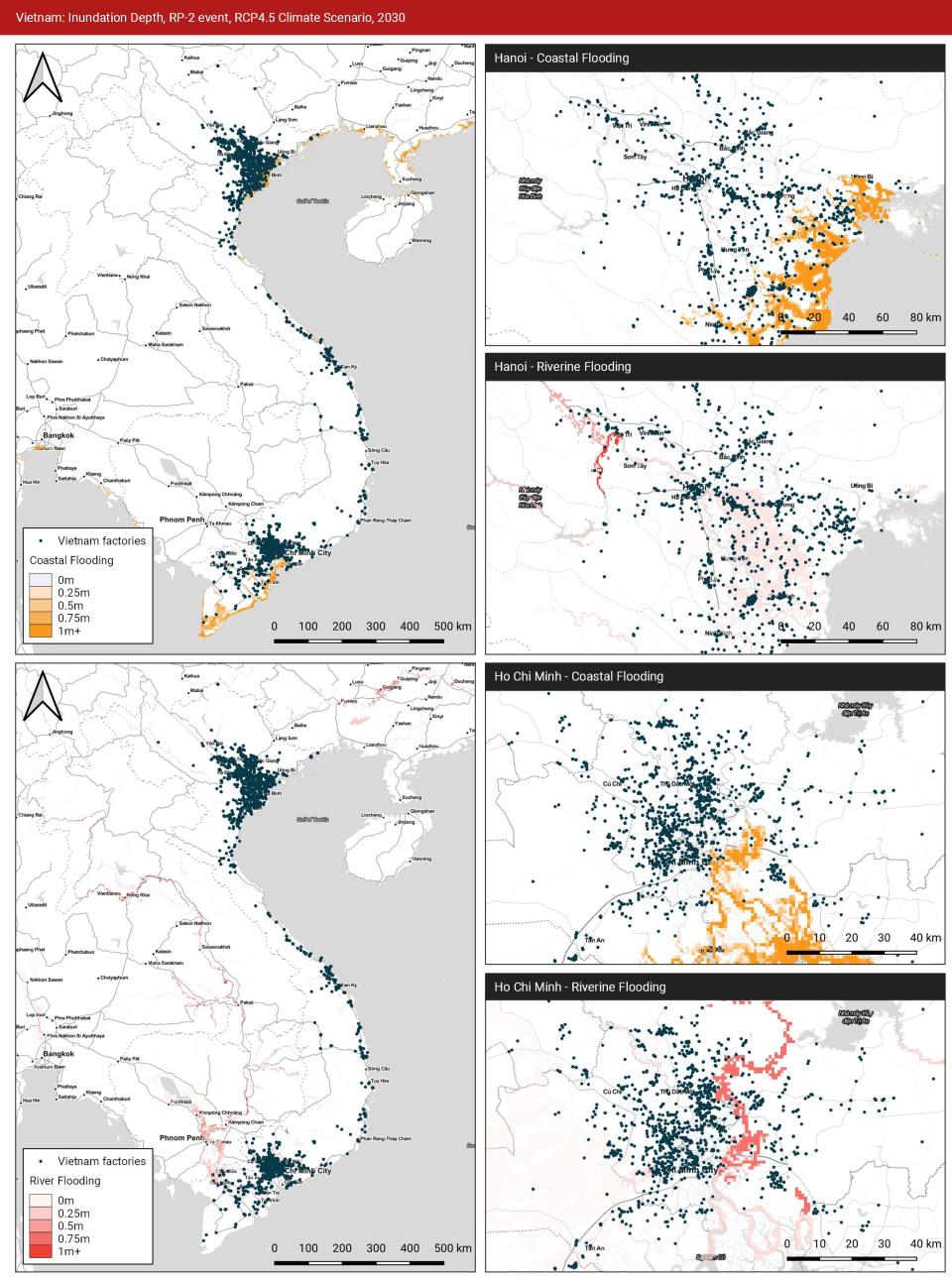

Using flooding models based on our middle-of-the-road climate scenario we map inundation levels for more than 8,000 apparel and footwear factories in our four focus countries. We estimate annual “disruption days”—the production days lost to flooding and recovery—in a non-adaptive scenario for each factory in 2030 and 2050 using the maximum “inundation depths” from coastal and riverine flooding for two-, 10- and 100-year events, or “return periods” (RP2, RP10, and RP100). As with heat-productivity impacts, we convert these disruptions into aggregate annual impacts on export earnings and jobs.

Taking one example, Figure 2 illustrates flooding in Vietnam, with coastal flooding represented in gold and riverine flooding in red. Deeper shades signal higher inundation levels at 0.25 meter intervals, up to 1 meter and higher. Apparel and footwear factories are shown in blue.

How will extreme heat and intense flooding impact apparel production in our four focus countries? Our calculations at macro level considered two growth scenarios: our “climate-adaptive” scenario presents the growth trajectory of apparel industries that move quickly to reduce heat stress for workers.

As the table here shows, the economic damage associated with failure to adapt to the physical effects of climate change could be profound. Pausing to reflect on the analysis presented above, we can make a couple of observations. The effects of heat become meaningfully worse, according to our analysis, between 2030 and 2050. Workers manufacturing goods for the six brands we focus on in our analyses face a sevenfold increase in exposure to extreme heat in these production centers, on average, between 2030 and 2050.

Flooding risk increases more gradually, however, and is generally a smaller, more isolated issue. The picture here is largely consistent with the findings presented in our first report. As we show, the consequences that these exposures could yield, in terms of value-at-risk or productivity headwinds, are potentially meaningful to brands and suppliers. And they have additional consequences for workers that depend on how their employers and buyers react. While the pervasive and large-scale effects of heat make it a systemically important subject for adaptation, the unpredictability of flooding means it is a potentially idiosyncratic cost, with severe impacts on individual suppliers and their workers, and therefore on brands and their investors.

Taking this assessment a step further, we sought to estimate the financial costs of these productivity risks at brand level. We presented the potential consequences of flood and heat impacts for brands or their suppliers in terms that can be considered proportionate either to the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) and operating profits of a brand, or revenues of a supplier. We found that productivity headwinds amounted up to 3 percent of COGS for Ho Chi Minh and Phnom Penh, or circa 5 percent of our sample brand’s global net operating profit after tax.

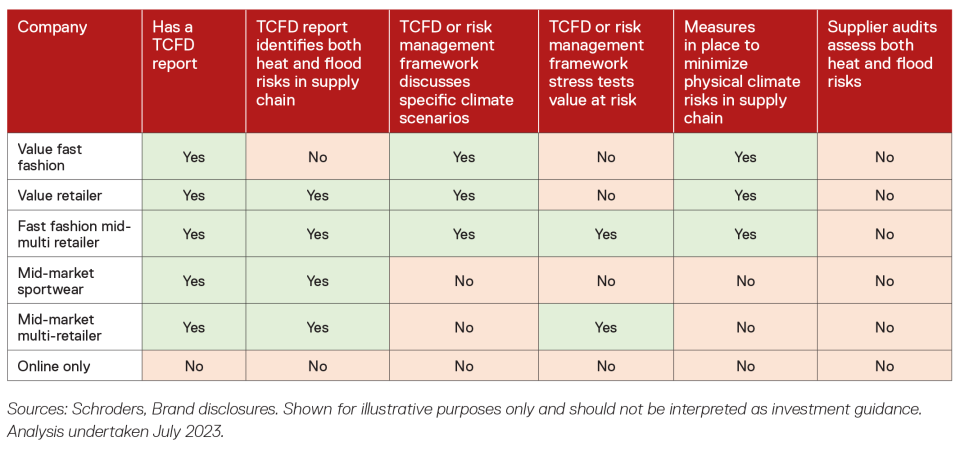

So, where are companies and suppliers in anticipating these risks? We undertook a bottom up analysis of the six focus companies’ Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) reports to determine the level of sophistication around reporting on physical climate risks. Whilst many brands have developed policies, processes and targets to address climate mitigation (e.g. establishing SBTi targets), we found that adaptation in the context of apparel manufacturing is lacking.

What does it mean?

The climate vulnerabilities of workers, manufacturers and of fashion’s substantial output in tropical and subtropical centers are measurable, and projections show these will only be exacerbated. Climate disruption is already cutting deeply into export earnings, employment, worker health and profits. Without rapid adaptation, these falloffs in earnings and jobs will compound.

Fashion buyers treat many ground-level social and environmental costs as externalities so there is real risk that brands and retailers will stay on the low road when it comes to climate adaption: compliance rituals such as heat measures as part of worker “wellness” programs and commissioning of flood hazard certifications, for example.

So, where is the higher ground?

It lies in the value chain adapting to climate breakdown: the associated productivity gains, and the additional earnings, income, health and jobs these bring. For workers, the need is clear enough. For manufacturers, the recouping of heat- and flood-related shortfalls in earnings makes adaptation feasible, if not attractive. For buyers and investors, unmeasured risk can mean long-term losses, and adaptation investments can yield both relief and rewards. For COP28 policymakers and private finance, adaptation investments and transfers are a smart and appropriate uses of loss and damage funds. For governments, new jobs and export earnings are crucial. Higher ground is where new rules generate action, accountability and a just transition.

Join Cornell GLI’s 2024 Conference on Friday, Feb. 2 in New York City. Registration and further details can be found here.

Jason Judd is the executive director, Cornell University Global Labor Institute. Angus Bauer is the head of sustainable investment research at Schroders, the London-based asset management firm.