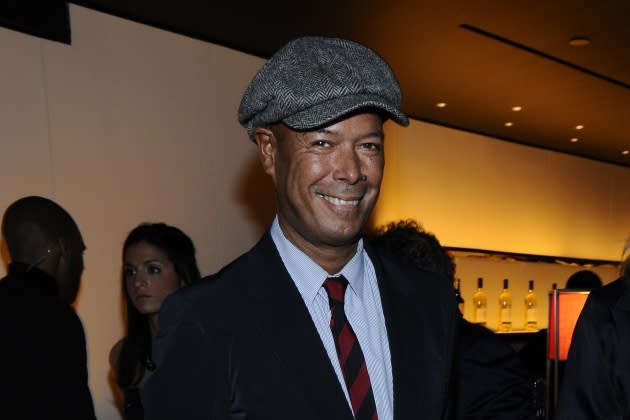

Fashion Journalist and Multitalent Michael Roberts Dies

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Fashion journalist was just one of many monikers that applied to Michael Roberts, who died Monday at the age of 75.

Roberts was believed to have been suffering from an illness prior to his death and was in Sicily, Italy, where he had a home, according to former colleague Amy Fine Collins. The cause of death was not immediately known Monday night. Elegant, exacting, as well as biting at times in his commentary, he rose to fame in the competitive media world with a well-honed work ethic.

More from WWD

A man of many talents, Roberts was a fashion journalist, illustrator, stylist, filmmaker, author and photographer. His media-heavy résumé was punctuated with such roles as Vanity Fair’s first fashion and style director, The New Yorker’s fashion director, the London Sunday Times’ style director in his homeland of England, Tatler’s art director, British Vogue’s design director, Vanity Fair’s Paris editor and a Condé Nast Traveler contributing editor. During his decades-long career, Roberts had two stretches at Vanity Fair — first under the magazine’s editor in chief Tina Brown and again under the reign of Graydon Carter.

In 2022, Roberts was honored with Commander of the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II for his contributions to fashion. Intercontinental, Roberts was largely based in Europe, and traveled frequently to the U.S., Rio de Janeiro and Asia, grasping globalism as a way of life, versus required biannual travel for fashion weeks, before most of his fashion peers. “Fashion’s global now. If you’re truly involved, you can’t be in one place any more,” he told WWD in 2006.

The industrious creative also illustrated and penned the vibrantly colorful story of his longtime friend Grace Coddington’s life from the point of view of a baby orangutan in “GingerNutz: The Jungle Memoir of a Model Orangutan.”

Having known Roberts as a stylist, writer and illustrator and “admired his wit and his eye,” Giorgio Armani said he was less familiar with Roberts’ work as a photographer. “Then, in 2007, I saw his book, ‘Shot in Sicily,’ and was impressed by his unique capacity for observation and his ability to capture the soul of that extraordinary Italian region, to the extent that I invited him to hold a photographic exhibition and a preview of his book at the Armani/Teatro,” Armani said. “Michael was a jack of many trades, a truly multifaceted creative, and above all a man of taste. I am deeply saddened to learn of his passing. I believe that people like him, with such broad views, are very rare to find these days.”

His films included the documentary “Manolo: The Boy Who Made Shoes for Lizards” about Manolo Blahnik. The designer recalled him fondly. “Goodbye my dearest friend. For me, you will always be irreplaceable, the most brilliant mind of my generation, a great artist, writer and illustrator. Much love, Manolo.”

Roberts’ talents were far from silo-ed.

“Each one informs the others. They’re not a stretch. Going from writing about fashion to drawing fashion to doing collages, to drawing at The New Yorker, to doing a film, which is about fashion — each one informing the other. And each one I learn from,” Roberts told WWD in 2017.

Never one to pull punches, Roberts was refreshingly blatant about his opinions. “There’s no bloody collaboration making a movie. A movie is one person thinking up the idea of the movie, bossing everyone else about doing the movie and getting the movie edited and done as well as one possibly can. There’s all this talk about collaboration — f–k collaboration. There is no collaboration. It’s usually one person arguing with 5 million other people in suits,” Roberts told WWD in 2017.

On Monday, Collins recalled their Vanity Fair days together and how “deeply knowledgeable” Roberts was about fashion, art and culture in general, as well as his old-school grandeur.

“Michael was very particular, with a very strong point of view about how things must be done. He may have been a little impatient with those in the industry, who did not have the sweeping frame of references that he did,” she said. “But he had to do things his way, and so he had fallings out with some of the people with whom he worked. The Manolo Blahnik documentary ended up not getting shown as widely as it should have been, because of internal disputes among those involved. Film and animation were further fields he was poised to conquer.”

Roberts was born in Buckinghamshire — about 30 miles outside of London, but considerably more staid. After studying at an art school in South East England, he relocated to London at 18 and worked as a Royal College of Art professor’s assistant. That connection led to one with The London Times’ fashion writer, and later his first foray into journalism. At times Truman-esque in his reporting — as in Capote — Roberts’ work ranged from chronicling a night on the town with Halston to profiling the aging actress Mae West, who reportedly saw an apparition during their Los Angeles interview.

In 2006, Roberts jumped ship from The New Yorker to join Vanity Fair as fashion and style director, causing a masthead shake-up and reshoots if needed. With the right instincts and the right taste level, Roberts was considered a primo choice for the magazine. When a potential cover shot by Mario Testino of Hilary Swank was not sexy or summery enough for him and other editors, Patrick Demarchelier was enlisted for another shoot.

His styling occasionally alarmed some, as was the case in 2008 when national outrage was sparked by back-baring photos by Annie Leibovitz of Miley Cyrus appeared in Vanity Fair in 2006. Addressing the kiddie porn allegations as “ridiculous,” Roberts said that teenagers could be seen on TV and in the cinema “in the most prurient ways” and the idea that he was “deemed as being party to some kind of subversive picture of this girl and that she was cajoled was completely not true.” He also cleared up the mischaracterization that she was wrapped in a bedsheet. It was a 83-inch Champagne-colored duchess satin stole — one of several that he had made for different photo shoots.

Roberts also excelled in the field of children’s books, where his painstaking three-dimensional paper cutouts that were reproduced as two-dimensional art were put on full display. True to form, “Snowman in Paradise” is told in verse about a snowman fed up with the winter chill who’s offered an escape to the tropics by a magical bluebird. Roberts, who lived at Anna Wintour’s house when he first moved to New York one winter from Europe for Vanity Fair, appealed to children and adults on different levels.

“Given a choice, does anyone really like mud and sludge and freezing your ass off?” he asked WWD at an Iman-hosted book party at Bergdorf Goodman in 2004. The storyline and bohemian color scheme of “Snowman in Paradise” ran parallel to how the famed French artist Paul Gauguin found inspiration in Tahiti. Roberts explained that the book relied on a little bit of charm, namely that you can discover things if you travel. He didn’t do those “kind of preachy Madonna-esque books,” he said. “I find them faintly annoying and aggravating.”

Recalling a story about the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Poiret exhibition at the Costume Institute that she worked on with Roberts and in which she included one of his Matisse-like illustrations, Collins said it depicted a famous coat worn by the couturier’s wife Denise, which for decades had only been known from photographs. The Met had acquired the actual coat from a once-in-a lifetime sale of Denise Poiret’s wardrobe. Collins said, “It was extraordinary finally to see this marvelous cocoon coat in person. I told Michael it was now possible to see the actual coat he was depicting for our story, before it even went on display in the exhibition. I was very excited about seeing this fashion-history treasure,” Collins said. “But I was puzzled — it turned out he had no interest in seeing the actual haute couture artifact. He already had his idea, it seemed, of how the coat had to look, his own artistic vision of it, which I suppose the real coat might have interfered with.”

The distinctly elegant Roberts was more than a style arbiter for jet setters, having been elected into the 2007 International Best Dressed List for the Fashion Professionals category. Artist Peter Schlesinger first met Roberts in London in the early ’70s through Schlesinger’s now late husband Eric Boman, a photographer. Roberts was then writing features and little pieces and doing illustrations for them in The Sunday Times. “We were all young together. It was fun to be with. He was someone I would see around. The social world in London then was small — that fashion, arty world,” Schlesinger said.

By chance, Schlesinger recently found a magazine clip from a 1973 edition of Honey magazine entitled “Could You Love a Man Who Wears Makeup?” in Boman’s archives. Roberts and Boman were featured in the piece with Roberts explaining that he started doing so in college as a kind of experimentation with all kinds of strange clothes. He had since scaled back relying on a very subtle daytime look and a more interesting evening one. Roberts said makeup was like when one first starts designing: “At first, you throw in everything but the kitchen sink. Makeup is a learning process like everything else,” he said. “I don’t believe in hiding behind makeup or looking totally freaked out like Marc Bolan — that’s dreadful, 1965, flower power and all that. I’ll agree that he’s the one who got everyone interested in makeup for men. But I think it should progress.”

And so it did, as have many other mediums Roberts worked in.

— With contributions from Luisa Zargani (Milan) and Samantha Conti (London)

Best of WWD