Fashion Insiders Azza Yousif and Michelle Elie on the Importance of Xuly.Bët Designer Lamine Kouyaté

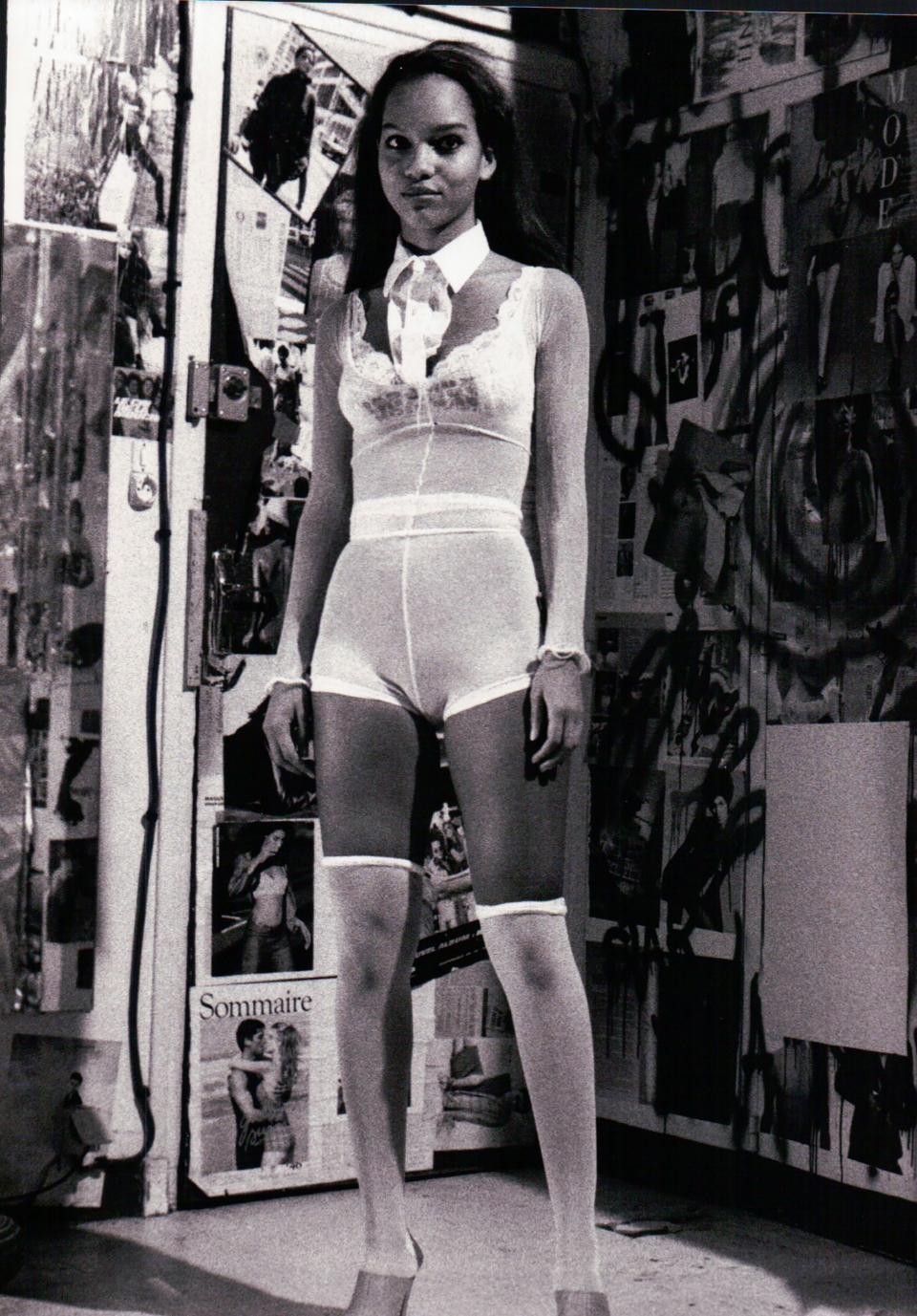

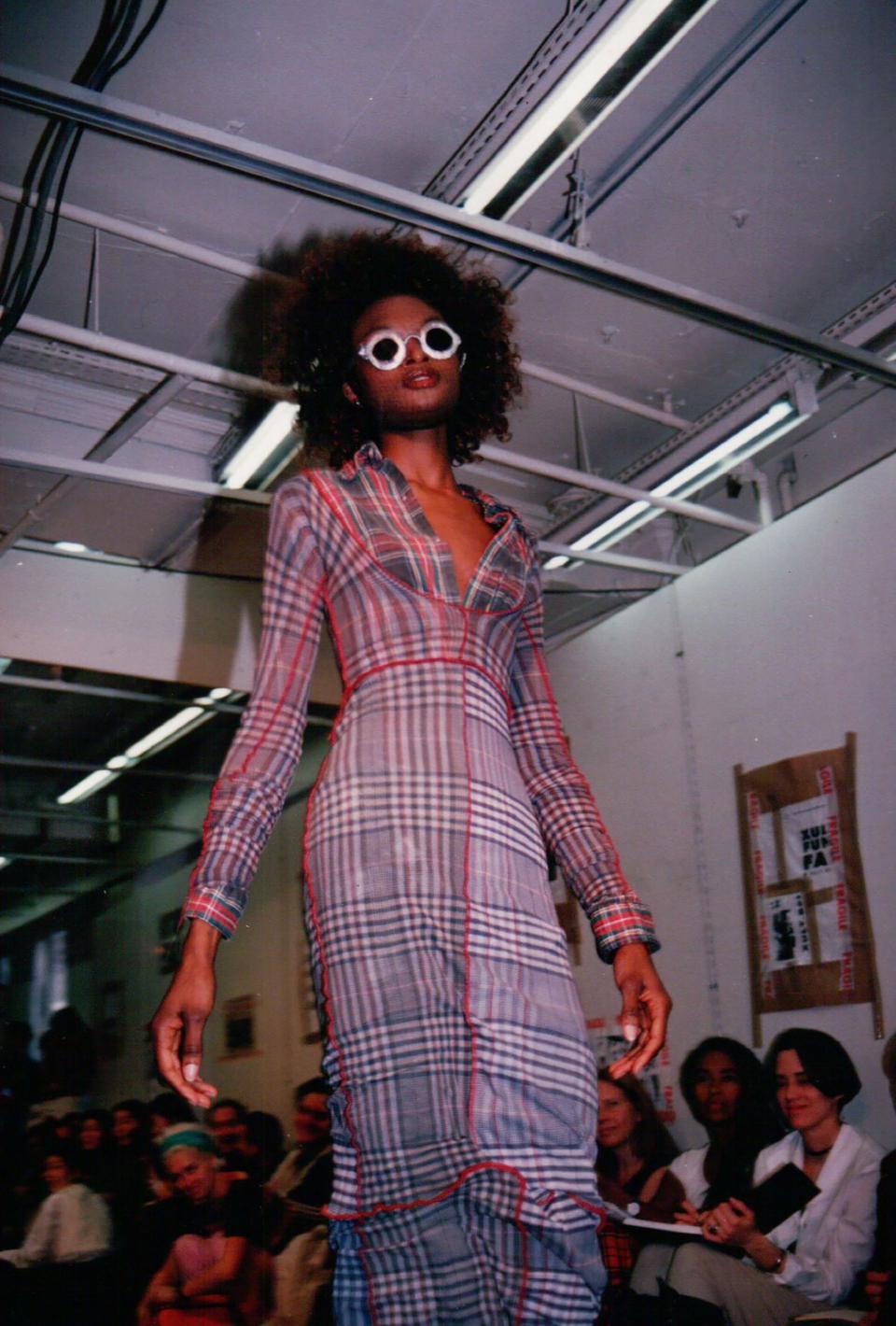

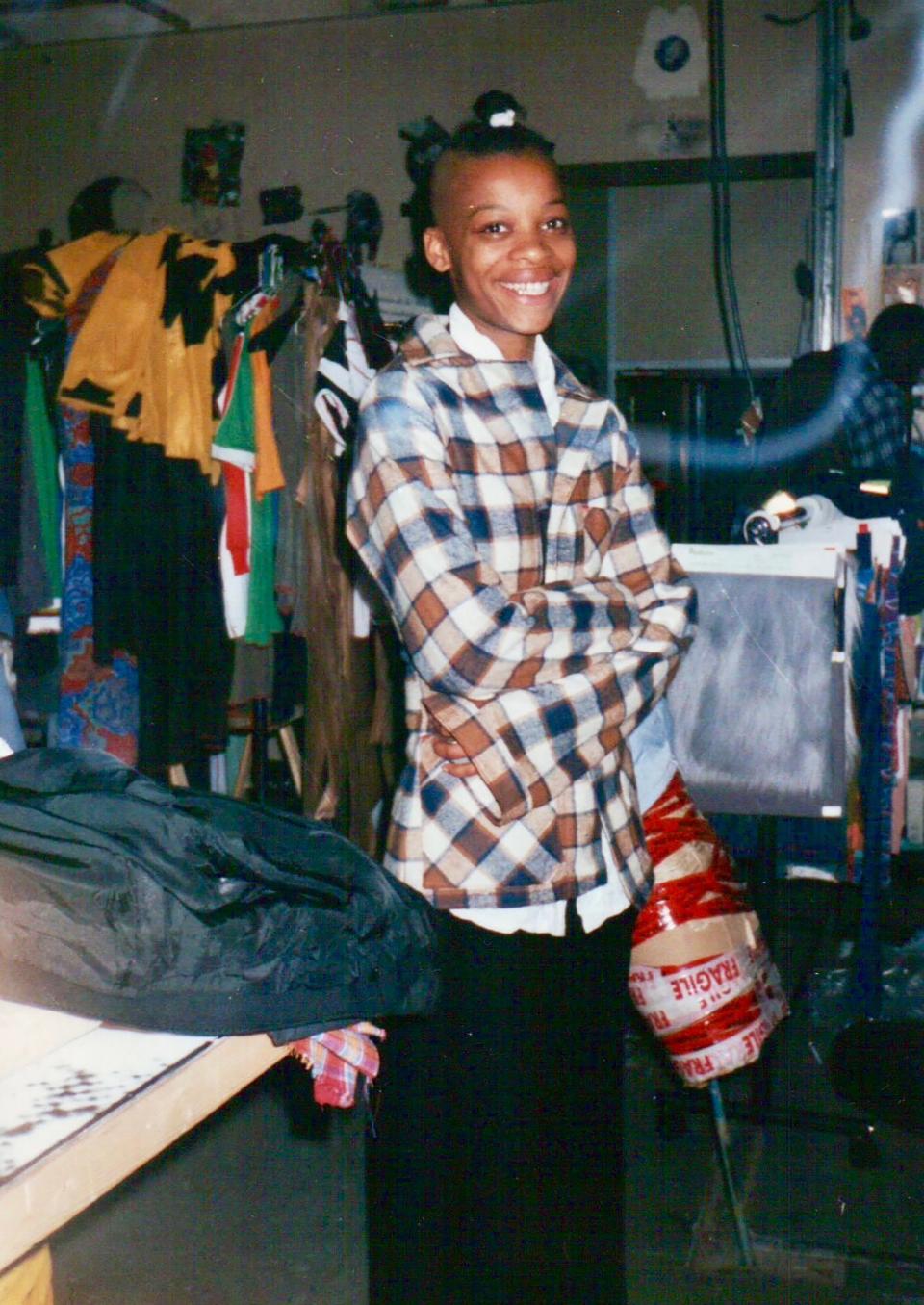

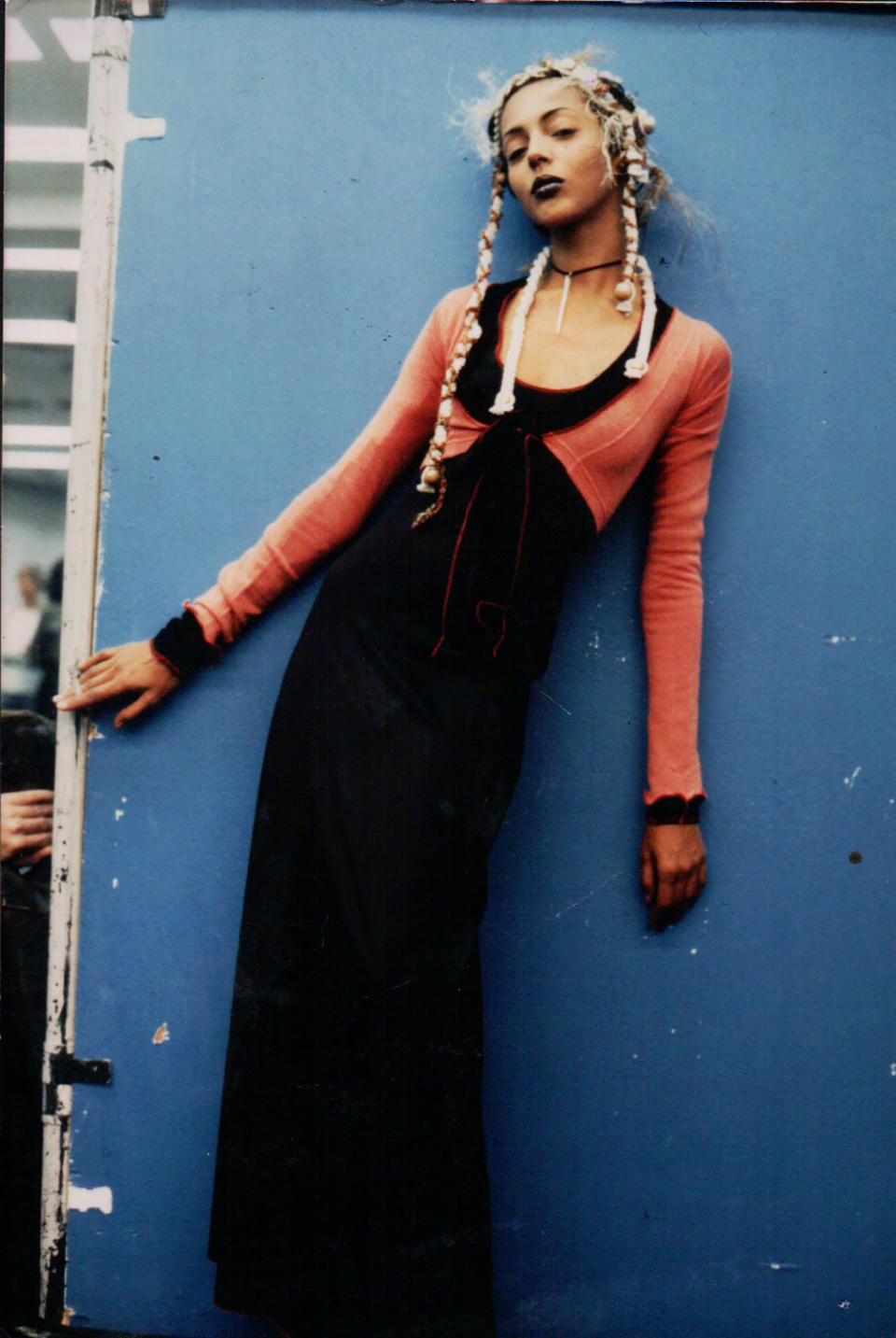

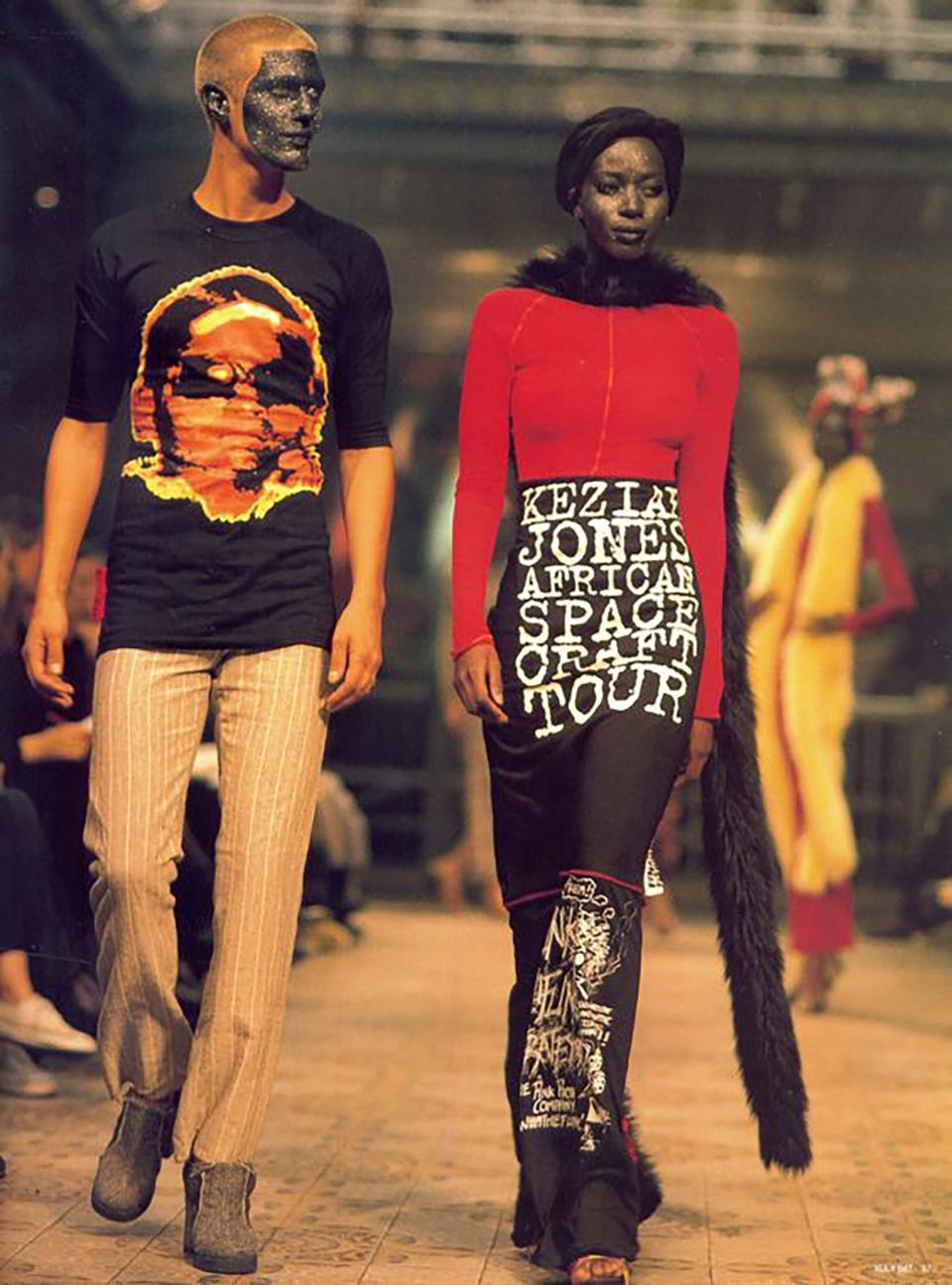

Archival Xuly.Bët Looks

From Xuly.Bët’s Archive

From Xuly.Bët’s Archive

From Xuly.Bët’s Archive

From Xuly.Bët’s Archive

From Xuly.Bët’s Archive

From Xuly.Bët’s Archive

From Xuly.Bët’s Archive

It is possible to be too far ahead in fashion. Xuly.Bët’s Lamine Kouyaté is a case in point. This Paris-based Malian designer was championing diversity, staging guerrilla shows, making shopping experiential (his New York boutique featured a skate ramp), and upcycling long before these issues were the foci of the industry. Yet his work is little known, in part because his most important work was done in the pre-internet 1990s.

The industry still has far to go in terms of diversity, both in terms of fostering the work of people of color—and preserving it. The upcoming Willi Smith retrospective at the Cooper Hewitt is important in terms of content, representation, and conservation. So is the updating of Kouyaté’s website to include archival documentation of his work. The project, launched this week, is a collaboration between the designer and Azza Yousif, stylist and Vogue Hommes editor at large. The news was met with an emotional response from creative director and street-style regular Michelle Elie, who owes her big break as a model to Kouyaté. “I was in tears as I reposted the images,” she tells Vogue.

Almost three decades into his career, Kouyaté is still a champion of diversity and sustainability, still representing an image of Paris that is too little known or shown. For Yousif this endeavor is personal: “I would love for Lamine’s contribution to fashion history to be recognized on a wider scale,” she says.

Here, Yousif and Elie speak to Vogue about the impact Lamine Kouyaté and Xuly.Bët have had on their lives and fashion.

How did you first become aware of Lamine Kouyaté and Xuly.Bët?

Michelle Elie: I met Lamine while modeling in Paris. I had heard of this new designer [who] was African, of Malian descent, and doing incredible things. Xuly.Bët was the underground fashion brand you wanted to be part of because he was capturing our youth. It was cool to book other [big] brands, but it was so much cooler to be part of the in-your-face energy of Xuly.Bët. It was family to me. Lamine just welcomed everyone. His energy was strong, powerful, and mega-cool. It was—and still is—this youthquake. Lamine [proved that] you could exist in fashion without doing [big] campaigns and editorial.

Azza Yousif: I think I was about 15 when I discovered Xuly.Bët. I would see all these beautiful black girls in Paris wearing these layered colorful Lycra clothes with apparent red seams and a big red tag. It was the brand to wear if you were sexy, proud, and in the know about real Parisian culture as opposed to the cliché of Parisian culture—you know, the white girl with the marinière and high-waisted jeans on a bike with a baguette under her arm. This was the real Paris: multicultural, mixed-race, postcolonial, sexual, liberated, hedonistic. Yes, Saint-Germain is Paris, but Château Rouge is also Paris.

What’s very important is that it was not the vision of the black woman as a statuesque object on a pedestal, as Yves Saint Laurent represented her. The Xuly.Bët woman was rugged and real. She was not looking down from her balcony, she was out in the streets having fun. My dream was to wear his clothes, and be one of these hot Xuly.Bët girls.

How did you come to work with Lamine?

Yousif: I was approached by Lamine and his CEO, Rodrigo Martinez, last year. Shortly before our meeting they had started following me on Instagram, and as I scrolled through their feed I think I must have manifested our encounter, as I remember thinking how great it would be to help relaunch the brand and give it the powerful impact it had in the ’90s.

Elie: I [met Lamine through the] film director Andrew Dosunmu and the stylist Annett Monheim. Lamine gave me my first big break. It was a great moment for me because I was very low in funds and motivation, but continued living in Paris waiting for [success]. I was booked for his very first show at Hôpital Ephémère. It was epic. There were just 11 girls, and nine of the models were black girls—you must understand at this time it was very rare to book so many black girls for one show. He was so ahead. Lamine gave everyone a chance to stage their beauty and their energy; you could do what you want on stage, just be cool and have fun! This was so fresh, and all the upcoming talented stylists, photographers, and makeup artists just wanted to support him.

Azza, you wrote that Lamine has “empowered black youth to feel beautiful and proud of their bodies and heritage.” Can you expand on that a bit?

Lamine’s womenswear was mainly body-hugging layerings of stretchy Lycra fabrics. Whether you chose to keep the layering spirit or break a look down and only wear a cropped wrap top with a body-con skirt, the end result was always quite sexy. Polyamide and tulle are such revealing fabrics that there was not so much left to the imagination. When I would see those black girls’ curvy bodies in his clothes I found them so beautiful! It made me embrace my own body and feel proud of my curves.

As for the heritage, Lamine integrated so much African culture into his style, and that had never been seen before. He made it okay to turn an African immigrant’s background and state of mind into beautiful, experimental, cutting-edge, internationally acknowledged Parisian fashion. So the message I got from that was, ‘Don’t be embarrassed because your family is different—embrace it! Mix it with your own experience, and create something explosive.’ His fashion made you want to celebrate your differences, instead of being ashamed of them and hiding them.

The photographer Horst Diekgerdes commented that the brand “was and still is important beyond fashion.” What does that mean to you?

Yousif: Horst was living in Paris at the time and understands very well how Lamine has surpassed the role of the simple “designer.” Lamine created a loving, open-minded community—as Michelle Elie described so well in her post. His brand has become a symbol of integration and a celebration of differences. We needed him then to widen the tolerance and acceptance spectrum, and we need him—and others—now to keep going in this expansion of what is considered to be beautiful and fashionable. I would not be who I am today if that brand did not exist then. The hope he’s [given] me, and others of my generation—that we could be proud of who we are—is inspirational on a human scale, and that kind of contribution to society is immeasurable.

Elie: Lamine’s work is still so vital. [He created] a platform for diversity from his very first presentation and paved the way for a lot of African designers. It was not only how he created his collections, but how he presented his shows. Lamine has been disrupting the fashion system since 1992. I remember that we were carrying radios and dancing in clothes for [that debut] show, which he [scheduled] right after Jean Paul Gaultier’s to make sure he was seen and heard. I totally identify with [his] pure vision and true guerrilla attitude.

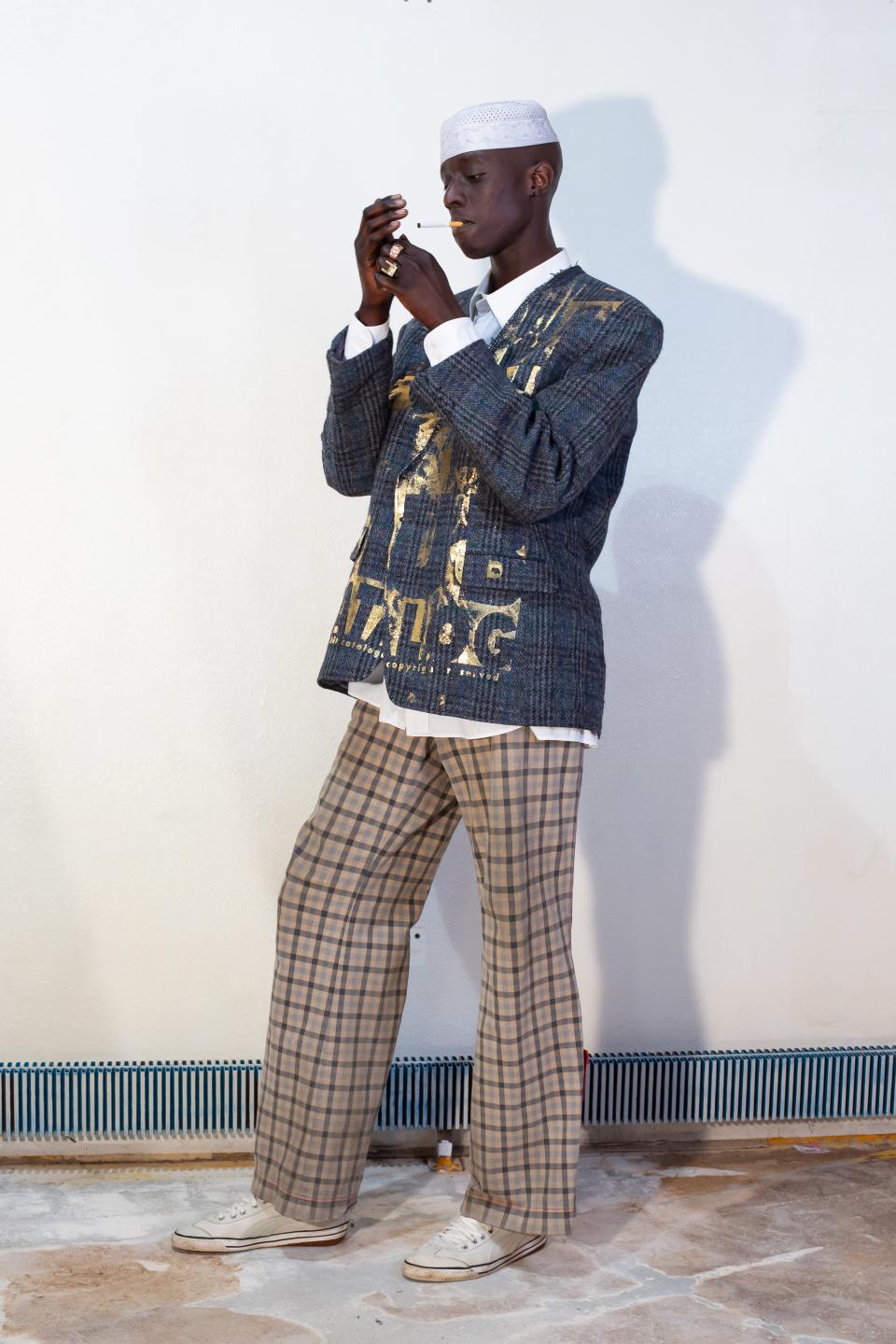

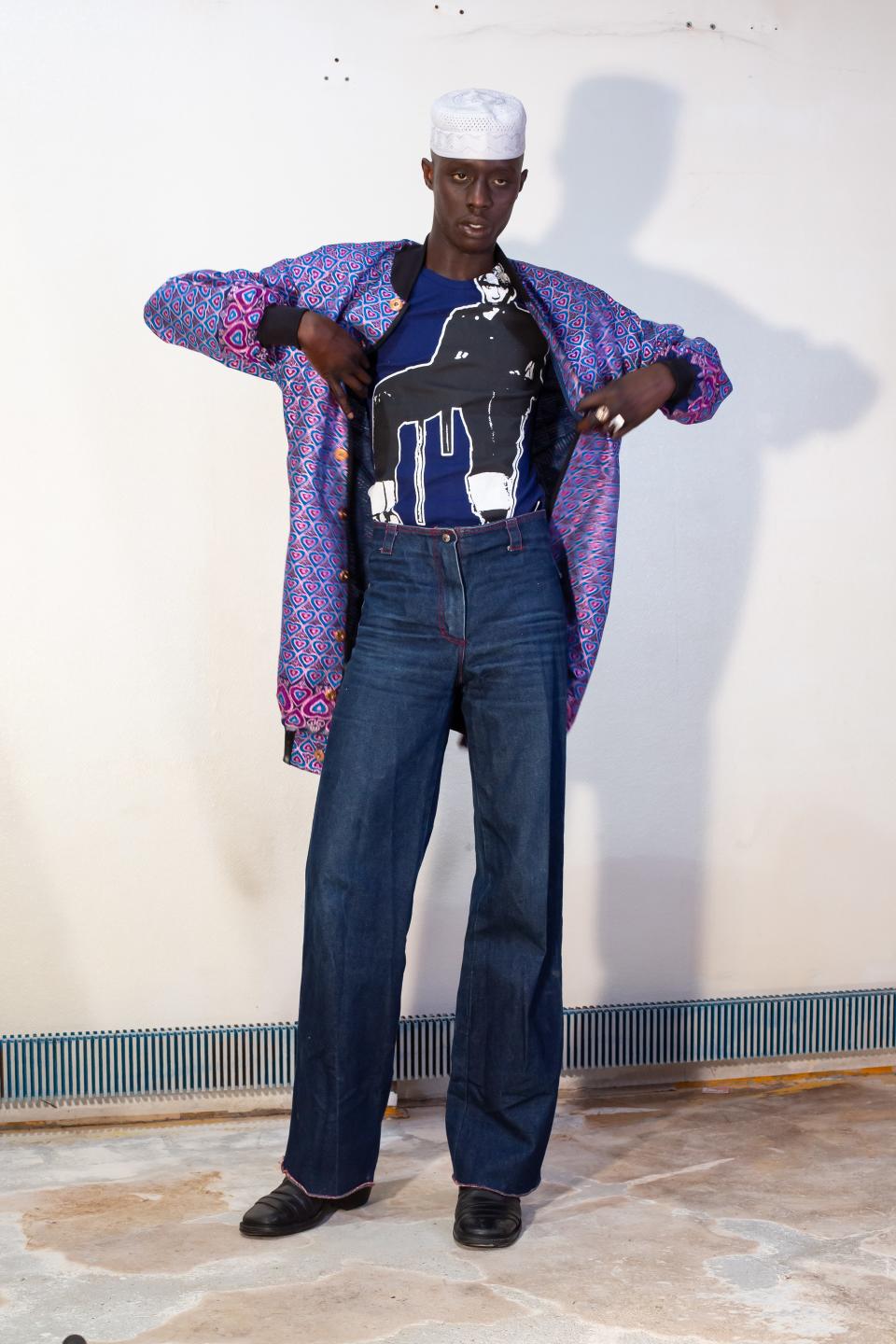

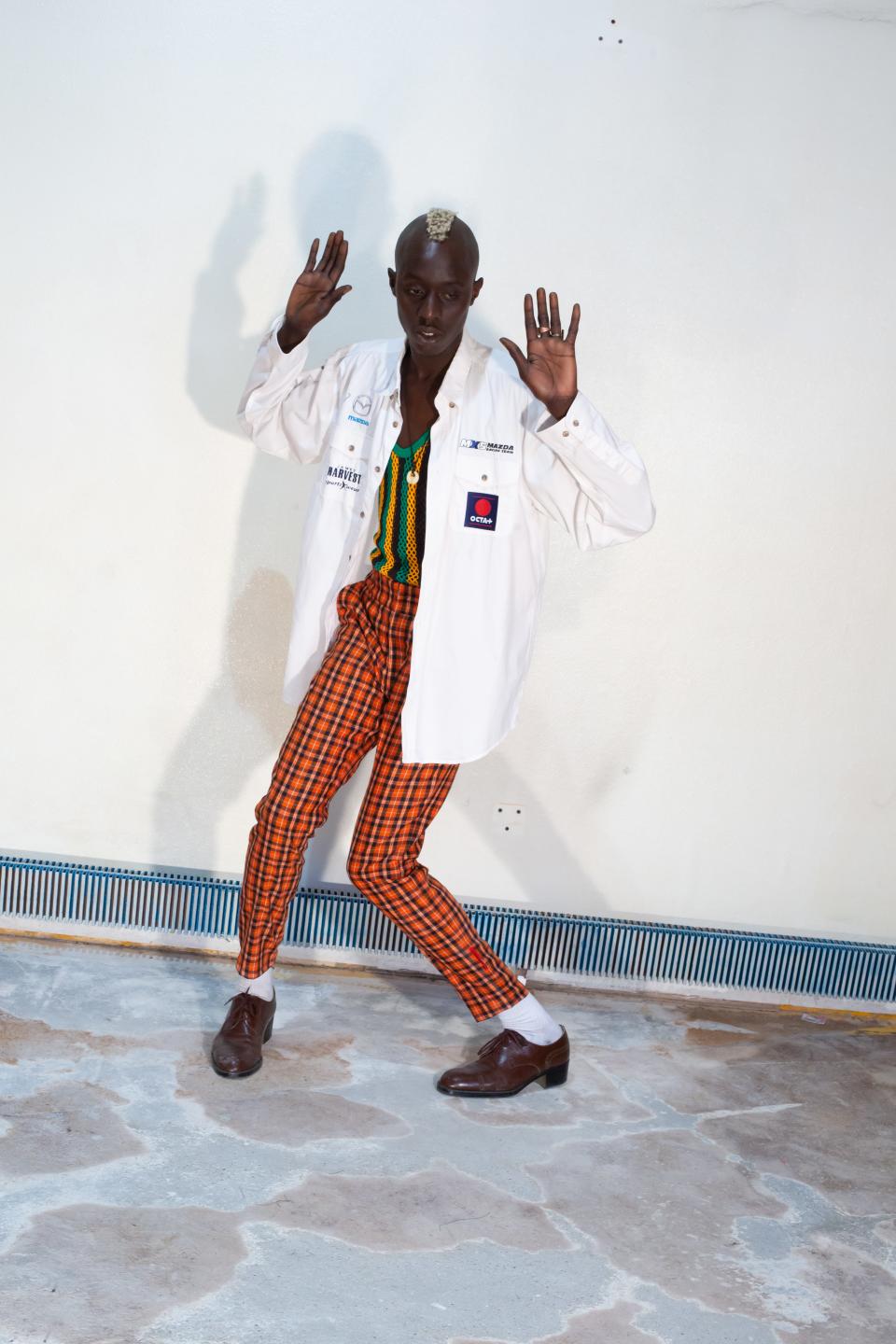

Xuly.Bët 09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

09.09.2019 Collection

Azza, can you tell us about the new 09.09.2019 collection?

Lamine never stopped designing, but his collections became more like sporadic outbursts, and the unpredictability of their availability made him difficult to follow. He struggled in keeping the rhythm of a classical SS-FW rhythm; it was just not adapted to his designs. So we agreed that from now on Xuly.Bët will deliver several drops in the year, directly on the website, each collection holding the name of the date at which it starts selling. Lamine will only collaborate with retailers on specific projects and capsule collections. The 09.09.2019 collection is a mix of new pieces made with deadstock fabric or upcycled garments. Some of the looks [are] made out of [vintage] sports jerseys, a concept Lamine started exploring when he designed a collection in with Puma in 1995.

Lamine’s been upcycling since launching the brand in ’92, and he’s kept experimenting with responsible fashion, whether by producing collections in Mali, or creating a collection in organic cotton, as he did in 2013. No waste and DIY, which are both culturally very African concepts, have always been the core of his ethos. It wasn’t an alternative concept, it’s just how he always thought things should be.

What do you think is the way forward for Xuly.Bët?

Elie: I am so happy and joyous to see that all through the changes in fashion, from analog to digital, there are still some brands that continue to keep pushing the envelope. I feel this energy to fight for fashion with a vision. I know times have changed, and one must not romance the past or be too retro in their thinking, but it is important to understand history, know the struggle, and understand that fashion is continuous hard work and passion and commitment. Lamine has remained passionate and committed to his brand vision and to himself.

Yousif: I knew I wanted to bring Malian artist Fatoumata Diabaté into the picture and have her photograph the collection. A lot of people feel like fashion creativity has plateaued as everyone is always referencing the same iconic images over and over again (mainly due to Pinterest and Instagram), but that is simply not true. It’s more about finding people who have a different life experience to yours, who have a beautiful vision, and creating a space for them to express it. This is also what Xuly.Bët is about: expanding people’s minds.

We shot the lookbook in Lamine’s atelier. Diabaté’s point of view was so important to our collaboration. How many female African photographers do you know? How exceptional that we got to work with an artist who set her embracing black female gaze on this collection. In her edit, she delivered a picture of Amandine (our model) shot from the back standing in front of these stacked boxes and what we call Tati bags. Those boxes are Lamine’s archives of VHS videos, show invitations, photo albums, vintage clothes, deadstock fabrics, African waxes. Here is this girl, staring at a wall of the legacy Lamine is leaving behind for all of us. This wall represents the history of Xuly.Bët. I simply adored how Fatoumata embraced what could be considered as a flaw, or a mess—and turned it into beauty [like] a sort of African Kintsugi.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Originally Appeared on Vogue