Fashion History Lesson: the Origins and Recent Strides of the U.S. Garment Labor Movement

The fight for labor rights in apparel manufacturing dates back to slavery, and it's still going strong today.

Welcome to Fashion History Lesson, in which we dive deep into the origin and evolution of the fashion industry's most influential and omnipresent businesses, icons, trends and more.

Clothes are made by people and, unfortunately, it would be an understatement to say that many of those people have struggled to be treated or paid fairly. The labor movement in fashion has made enormous strides over the last few years, though. Between the implementation of California's garment labor protection law (SB62), the subsequent nationwide anti-wage theft bill (the FABRIC Act) and the introduction of the New York Fashion Act, the push for better conditions and pay for garment workers is strong in the United States. That momentum, however, has been moving for well over a century, and much of the fair labor movement in fashion is built into the foundation of the labor rights movement at large.

Tracing fashion labor movements in the U.S. is a way to better understand the history of the nation as a whole. The same people who fought for equal rights are the ones who have forced change in fashion throughout the last two centuries. Below is an (extremely) brief overview, which should serve as a small piece of context for the current efforts we're seeing across the industry.

The cotton industry and Emancipation

To understand the fashion labor movement in the United States, we have to first look at the impact of slavery and the cotton industry.

"[Cotton] was the dominant industry in the United States leading up to the Civil War, and it was in partnership with the textile industry in the north," says Elizabeth Cline, author of "Overdressed" and "The Conscious Closet," who teaches a class at Columbia University on fashion labor history. "Cotton was a significant part of U.S. exports."

In extremely brief and broad terms, the fashion industry around the world was built on the forced labor of Black people. The fight for abolition is where the labor movement, as it impacts the production of garments, begins.

The ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1863 meant that the cotton industry could no longer run on forced labor, but with an exception: "as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." This meant that imprisoned Black people – who were penalized through a racist system of codes — would still work on the cotton farms.

In the years following, during Reconstruction, there was a movement to make equal rights, including in labor, the law of the land. Some more reading on this period:

How slavery became America's first big business, by P.R. Lockhart for Vox

Empire of cotton, by Sven Beckert for The Atlantic

How the 13th Amendment kept slavery alive, by Daniele Selby for the Innocence Project

The desegregation of textile mills

In the decades after Emancipation, the Southern part of the United States began to industrialize, and textile mills became one of the most significant employers. Still, the white owners segregated the work in the mills under Jim Crow Laws.

In his book, "Hiring the Black Worker: The Racial Integration of the Southern Textile Industry, 1960-1980," Timothy Minchin explained that the most arduous labor was given to Black workers.

"For the most part, mill owners hired only whites to work inside the mills. On the rare occasion that textile managers did try to hire Black laborers to run the machines, whites resisted, often by striking in protest," he wrote. "Some African-American men did receive paychecks from the mills, but typically they worked outside in the yards cleaning up and lifting heavy bales of cotton; if they got a position inside the plant, it was almost always as a janitor or sweeper."

The fight to desegregate textile mills was decades long. As more labor moved to the South in the early 20th century, Black workers fought to have mills integrated. Even into the 1970s, there were strategic lawsuits, such as Lea v. Cone Mills, which saw three Black women — Shirley Lea, Romona Pinnix and Annie Tinnin — successfully argue that Cone Mills denied them employment based on their race and gender.

You can read more about this from the Community Histories Workshop (CHW) at UNC-Chapel Hill and Heddels.

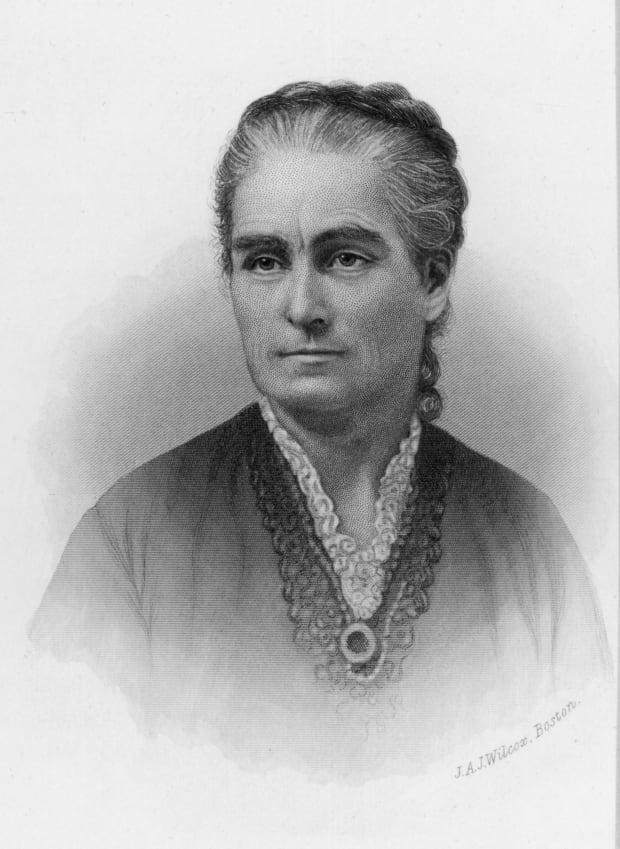

Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Industrialization and the Lowell Mill Girls

In the United States, the North began industrializing much earlier than the southern states. It wasn't uncommon for young women to enter the workforce to supplement their families' incomes. In New England, women moved from farms to Lowell, Massachusetts, where there were large textile mills.

Initially, these jobs were lucrative enough to support the changing dynamics of an industrialized country, with the women being paid decently and provided with housing. However, the mills began to take advantage of an influx of Irish immigrants in the area, paying them less and working them more. So, the mill girls began to organize.

By 1830, they had formed the first women's union attempting to gain a 10-hour work day and higher wages; they also formed one of the first significant labor strikes in the country. Unfortunately, the influx of workers allowed the mills to take advantage of their strike and continue to decrease wages.

In 1883, former mill worker Harriet Robinson wrote in her book, "Early Factory Labor in New England" about the strikes' results: "It is hardly necessary to say that, so far as practical results are concerned, this strike did no good. The corporation would not come to terms. The girls were soon tired of holding out, and they went back to their work at the reduced rate of wages… The ill success of this early attempt at resistance on the part of the wage element seems to have made a precedent for the issue of many succeeding strikes."

You can learn more about the Mill Girls of Lowell at the National Parks Service.

The 19th-century immigration boom and tenement factories

Like in New England, there was an immigration boom in New York City at the turn of the 19th century. And as thousands of people from Italy and Ireland moved into tenement housing, they were hired to work in sweatshops that operated both in their homes and in small, unsafe factories.

These workers were subject to harassment, wage theft via piece rate (a practice of paying per item created) and horrible conditions. In the early 1900s, they moved from hundreds of small factories into fewer electric factories further uptown. According to the New York City Tenement Museum, this allowed for workers to "build support… discuss unsafe and miserable working conditions." This became the foundation for the largest garment workers union in the United States.

"The International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA) paved the way in bringing attention to low wages, unsafe working conditions and excessive working hours of workers in the garment industry in the early 1900s," says Workers United's Theresa Haas.

Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire and its aftermath

Even with the organization of workers improving, conditions remained dire. It wasn't until a massive and deadly fire broke out at New York City's Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in 1911 that the movement gained national attention.

"On March 25 of that year, 146 shirtwaist makers (most of them young immigrant women) either died in the Triangle Shirtwaist fire that broke out on the eighth floor of the factory or jumped to their deaths," Haas says. "Many of these workers could not escape because the doors on their floors had been locked to prevent them from stealing or taking unauthorized breaks. More than 100,000 people participated in the funeral march for the victims, and a Committee on Safety was established in New York to prevent such a tragedy from occurring again."

Due to the national attention on the strikes, there was significant progress in conditions and pay. The Factory Investigating Commission was signed into law in New York, which allowed the government to investigate factories and enforce safety codes and employment rules on hours, child labor and wages.

For years, garment unions continued to fight for regulations on hours and wages in the U.S. One of the leaders of the movement, Rose Schneiderman, worked with President Franklin D. Roosevelt as the only woman on his New Deal advisory board. As historian Hasia Diner revealed in a PBS documentary about her: "She realized that the issues of labor and workers' rights cannot be settled outside of the political arena. It wasn't enough to negotiate with the boss of this factory or that factory, and it required systematic restructuring of society."

From 1937 to 1944, Schneiderman was New York state's secretary of labor, amending labor laws so that they applied to domestic and farm workers.

A movement undone

After a period of much-needed improvements to the lives of workers in the U.S. garment industry, things began to swing back. By the late 1970s and 1980s, the state of their livelihoods was changing once again.

"We were in a phase of free market fundamentalism and reticence to use government action to make change for decades," says Cline, noting that this ran up until the 2008 financial crisis.

Part of this market-knows-best mentality was paying as little for labor as possible. Jobs began to move underground or overseas: Some brands took their manufacturing to Asia and South America, while others worked with factories that kept prices low by paying a new wave of immigrants as little as possible.

"We're really just getting out of that mentality," Cline argues. "Part of it was just a political challenge — the appetite to regulate the fashion industry just wasn't there."

El Monte and the formation of the Garment Worker Center

While the garment district in New York saw factories shutting down, manufacturing in Los Angeles grew, with much of the workforce made up of immigrants from Mexico and South America.

Throughout the '80s and '90s, the growing demand for fast fashion required cheap labor to keep prices low, which led to the proliferation of sweatshops and illegal factories — and a deterioration of working conditions.

This came to a head in 1996, when authorities found that 70 people from Thailand working at California's El Monte factory had their passports stolen, were forced to work and were paid as little as $300 a month, working seven days a week.

The Garment Worker Center was developed in the wake of El Monte, in 1995, when workers needed a space dedicated to advocating for their rights. In the early stages, they campaigned to pass the Garment Worker Protection Act (AB633), which "mandated an expedited wage claim process, created a registry and registration fees for garment manufacturers, established a restitution fund as a payor of last resort for workers who received a decision in their favor in their wage claim," according to a spokesperson for the group.

The problem was that there was a loophole in the law that made it possible for piece rates to continue. Workers were — and some still are — making around $200 a week for full-time work. Plus, the liability structure protected brands from having any repercussions.

Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Covid-19 and the resurgence of a movement

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the whole world saw the vulnerabilities in the supply chain, including fashion. Factories closed down without paying for work already completed, and some forced workers to make masks without giving them proper safety equipment to protect them from the virus. In many ways, these injustices put energy behind an existing movement to pass another anti-wage theft law in California. In my book, "Worn Out: How Our Clothes Cover Up Fashion's Sins," I traced the impact of the pandemic on workers around the world.

After years of work, SB62 passed in September 2021. With it, workers have a path for recourse when they experience labor violation in the golden state.

In the months following, Senator Kirsten Gillibrand's office announced a federal bill titled the FABRIC Act. It's based on the principles of SB62, and also includes a nearshoring tax credit to incentivize brands that moved to manufacture overseas to bring some back to the United States.

What it could do, Haas explains, is "establish joint and several liability requirements through which workers can hold fashion brands and retailers responsible for the labor practices of their U.S. contractors, bringing a level of legal accountability that has been sorely lacking in the modern apparel industry."

The FABRIC Act will be reintroduced in the next session of Congress. Garment and textile workers are also looking toward the passage of the ProAct from Senator Bernie Sanders, which would protect workers' right to organize.

Never miss the latest fashion industry news. Sign up for the Fashionista daily newsletter.