Fashion Designers’ One-liners Featured in Marylou Luther’s Vibrant New Book

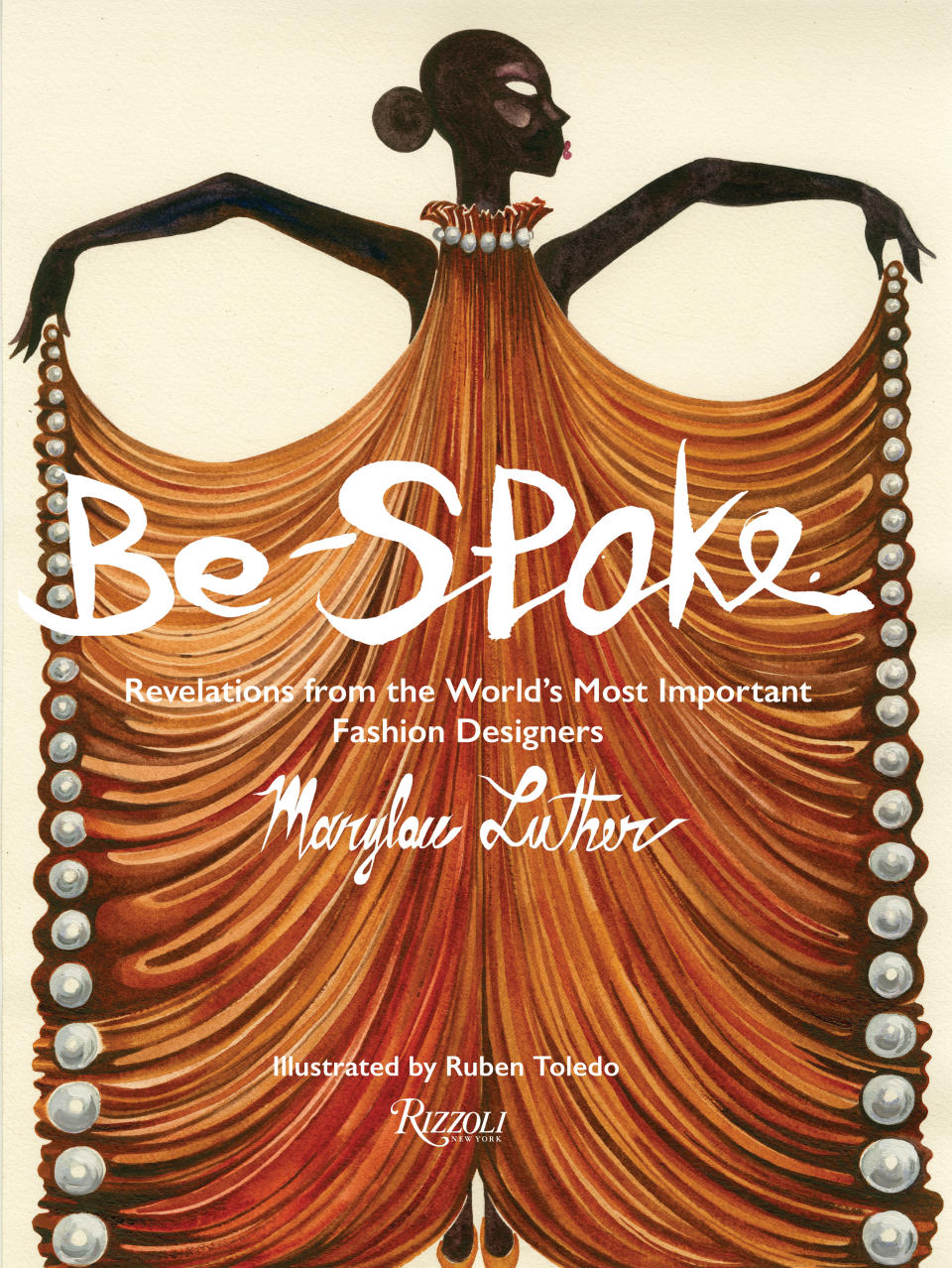

Improbable as 70 years as a fashion journalist might seem, Marylou Luther remains ever-questioning and curious. A chronicler of more trends than she could ever count, the Nebraskan has been rooted in New York and traveled internationally for decades. All those years of interviews have given Luther a fine-tuned ear for the quotable, and now many of the bon mots that she elicited from designers fill “Be-Spoke: Revelations from the World’s Most Important Fashion Designers.”

With a career that stretches back to the era when Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, Cristobal Balenciaga and other esteemed designers ran their namesake houses, the author’s perspective has widened as the fashion industry has burgeoned. Yohji Yamamoto, Demna Gvasalia, Alexander McQueen, Thom Browne, Rei Kawakubo, Michael Kors, Alexander Wang, Ricardo Tisci, John Galliano, Raf Simons, Alessandro Michele and Derek Lam are among the other featured designers in the colorful Rizzoli-published tome that features vibrant illustrations by Ruben Toledo.

More from WWD

At times during a recent interview, the 92-year-old instinctively answered a question with a question or flipped a question back, eager to hear another opinion. In highlighting how “Be-Spoke” came to be, Luther also detailed some of her own memorable events in spotting the waves of fashion. The idea for the book surfaced while sifting through her files three years ago and noticed one titled “Designer Comments.” After floating the proposition by her friend of many years Toledo, who was game for the creative endeavor, Luther was off and running.

More than anything, the author wants people to know that designers have something to say, more than just the clothes that they produce. Case in point is André Courrèges, who predicted that trends that impact society for seven years or more always begin after a major calamity or a scientific breakthrough: Fashion flowered in the 1930s following the stock market crash; Christian Dior’s New Look of 1947 emerged after World War II; the youthquake of the 1960s followed the introduction of the pill, and the pants revolution followed man’s landing on the moon.

What intrigues Luther now about that statement is nearing the three-year anniversary of the global pandemic, “What is that moment? Is it a moment of caution, comfort, historical repeats, multisexual clothes, minimalism, maximalism, artificial intelligence, outer space, Hollywood?” she asked.

From her standpoint, how fashion reflects the upheaval of the past few years comes down to “escaping it with clothes, or trying to escape, or looking back to the past.” Unabashed about favorite designers, Luther cited Courrèges, Christian Lacroix and Rick Owens. Speaking of the latter, she said, “I have always favored creativity. I understand the brand [status] and that clothes have to sell. But the thing I’m always looking for is something I don’t know about. I want to learn. I want creativity. Rick is overflowing with it.”

Kerby Jean-Raymond also earned her acclaim for “bringing Black design to the public” and to the forefront through his presentations and shows. “That first event really opened people’s eyes to what is possible with Black designers,” Luther said. Christopher Kane and Jonathan Anderson are two other talents, she said.

Hopeful that fashion is “still design-driven instead of I’ll-swap-you-my-dress-for-your-quote,” Luther said, “The days of the big, big brand are a little perilous right now. I know statistics show that the big brands are doing just fine. I don’t know how long that is going to last.”

Among the many insights were Oscar de la Renta’s recollection of how his apprenticeship at Balenciaga involved picking pins up off the floor, and years later the greatest surprise about designing couture for Balmain was there were no sewing machines in the atelier. Hedi Slimane spoke of how the shoes set up the tone and attitude.

Her foray into fashion happened in the late ’50s at the Des Moines Register newspaper where she was informed that she was taking on the fashion editor job that previously had been held by the niece of Carmel Snow and her uncle owned the paper. An inaugural trip to couture left Luther with many questions, such as why Dior’s tulip look did not feature any images of actual tulips.

Despite feeling “like a complete idiot,” she was marched off to New York to cover fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert’s Press Week, which featured only designers that she represented. During her next post at the Chicago Tribune, she helped “start a real freedom of the press in fashion journalism,” by campaigning to cover the shows when the buyers were looking at the collections instead of later during Lambert’s prescribed time, Luther said.

More than anything, she would like to see continuous dialogue with college students and young people about their views on fashion, as opposed to sound bites on social media. ”One-on-one conversational exchange is extremely important, because you’re not registering that you said something clever on social media but didn’t really mean it.”

While speaking with some students at the Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising and FIT, Luther was flummoxed that they had no idea who Rudi Gernreich was — the designer that is credited with creating the bikini. Improving educational fashion programs with more information about designers of the past is something that she would like to see happen.

On another front, Luther said she would like to see a greater appreciation for the historic importance of Hollywood costume design versus red-carpet awards show media coverage that “might help to keep it in the news of the day or the week.”

During another stop in Luther’s career, she worked at the Los Angeles Times in a period when the few designers that came to Hollywood “all wanted to meet Edith Head.” The fashion editor was happy to oblige, as they were neighbors, and her husband was friendly with Head. (So much so, he was a pall bearer at the costume designer’s funeral.)

Luther said that Head, “an amazing woman,” once explained that although Hubert de Givenchy designed Audrey Hepburn’s little black dress in the 1961 film “Breakfast’s at Tiffany’s,” there was no mention of Givenchy in the credits. The rule in Hollywood at that time was the costume designers were credited with all the deigns that were worn in a film, Head once explained to Luther. “She knew that Audrey wanted to wear Givenchy. Audrey would bring the clothes she wanted to wear. I don’t think Edith ever met Givenchy,” Luther said.

The first time Luther met Head was in a trailer on location, where Luther found herself facing Head’s eight Academy Awards. “She said to me, ‘I do this on purpose. With a Hollywood star staring at those eight Academy Awards, they can’t say, ‘Well, look Edith.’ There was truth in that.”

As for how all the years later Luther would like to see fashion change, she said she is keen to see someone fulfill Courrèges’ aforementioned quote and create a long-lasting post-pandemic fashion change.

In the meantime, perhaps Jonathan Anderson speculated about the road ahead most collectively in her new book, “As a body of people who work in fashion, we need to start thinking forward. It cannot go back to how it was. And if it does — then it will collapse,” he said.

Best of WWD