What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in Feud: Capote vs. the Swans

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

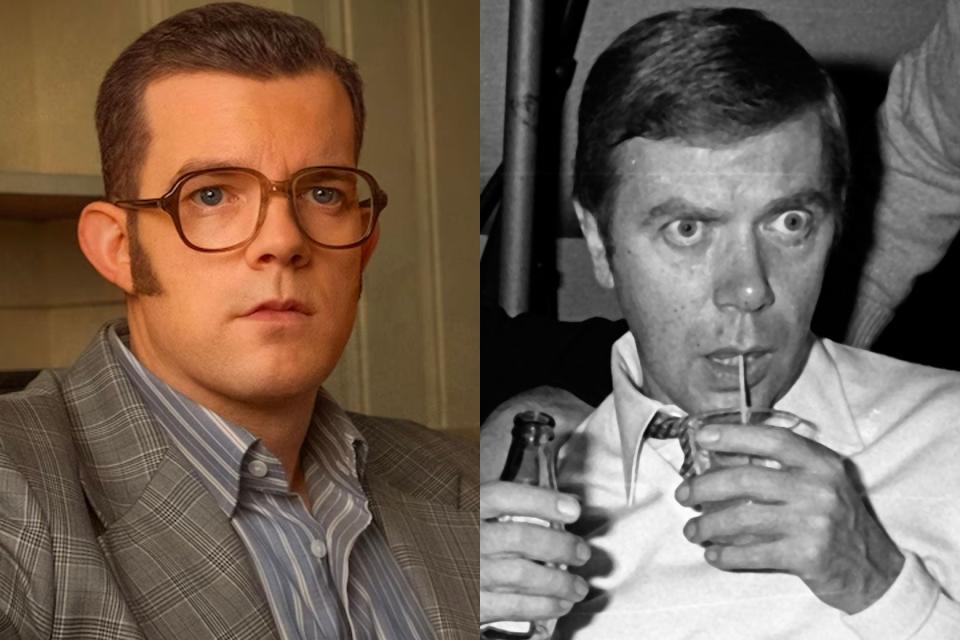

Remember how in the most recent season of The White Lotus, Tom Hollander played the ringleader of the “murder gays” who lured the hapless, loveless billionairess Tanya to her doom? That’s pretty much the same energy he brings to the version of Truman Capote we meet in Feud: Capote vs. the Swans—more literary and less homicidal, to be sure, but equally duplicitous and manipulative as he insinuates himself into a bevy of more sophisticated but similarly needy socialites (“the titular Swans”) Capote cultivates as soulmates, useful connections, and, ultimately, source material.

What we don’t get from the series—which is an eight-parter currently rolling out weekly on FX—is a sense of Capote in his prime: the elfin beauty who became a literary sensation at 23 with the publication of his first novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms, despite only having a high school education. The book jacket photo on Other Voices, Other Rooms—a languid, seductive pose with a strong “paying for grad school by escort work” vibe—generated as much publicity as the prose itself. Like a time-traveler from the 21st century, when artists are expected to be as good at marketing themselves as they are at doing their actual art, Capote devoted as much effort to building his brand (fey, waspish, moonlight and magnolia) and cultivating his power network as to actually writing. Until by the time Feud catches up with him, promotion had completely taken over from any literary production.

Executive producer Ryan Murphy has likened the Swans to a sort of mid-’60s version of The Real Housewives of New York City, and to the extent that he’s using it as shorthand for women who (largely thanks to their husbands’ resources) are models of aspirational consumption, he is correct. But the Swans were products of a very different world, one which valued qualities like breeding, elegance, and discretion (not the first words that come to mind in relation to The Real Housewives of Anywhere), where ladies were supposed to have their name in the news when they were born, when they married, and when they died, and anything else was to be avoided. So while today’s Housewives might have been secretly pleased by having their dirty laundry spilled in a roman à clef with the resulting prospect of a zillion remunerative clicks, the Swans were horrified by Capote spilling their beans in an explosive 1975 Esquire “fictional” story, “La Côte Basque, 1965.” Soignée and well-educated as they were, when the Swans confided in Capote about their rivalries, affairs, and insecurities, they forgot the truth of Graham Greene’s observation in his autobiography A Sort of Life: “There is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer.”

They could perhaps take some consolation from the fact that Capote was known for giving new meaning to the words “unreliable narrator,” so all his gossip was to be taken with a large grain of salt. “I’ve talked to many people who didn’t trust him. Mike Nichols once said to me that Truman was the only person he ever met that lied about people just to hurt them,” Feud’s scriptwriter Jon Robin Baitz recalled. Here, we try to sort out where Feud, in its first three episodes, sticks to the facts and where—either on purpose or misled by the wayward Capote—it doesn’t let them get in the way of a good story.

In 1955, Bill, the president of CBS, and his wife Barbara “Babe” Paley (Naomi Watts)—the queen of Capote’s Swans—are with their friends David O. Selznick (producer, with Babe’s brother-in-law Jock Whitney, of Gone With the Wind) and his second wife, Jennifer Jones, on the CBS private jet getting ready to zip off to the Paley house in Jamaica. But they’re waiting on the tarmac, martinis in hand, for the Selznicks’ friend “Truman” to board. Bill assumes the group means former President Harry S. Truman, until he is informed that the guest is a novelist.

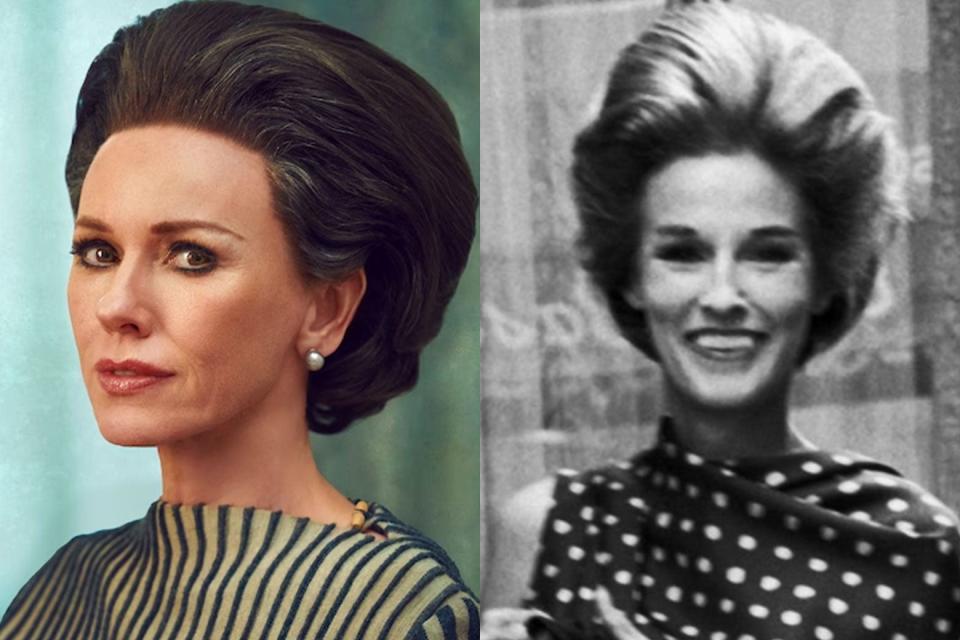

This is a good joke but is most likely invention. For one thing, in her autobiography Slim, Memories of a Rich and Imperfect Life, Slim Keith (another of the Swans, played by Diane Lane) wrote that she first met Capote in the early 1950s at a party given by Diana Vreeland, something she would most likely have mentioned to Babe Paley, while Capote’s publisher Bennett Cerf recalled that the author met Babe through friends around this time. Even if she hadn’t actually met Capote yet, Babe (and probably both Paleys) would definitely recognize the name as one of the best-known young novelists in America at the time. Finally, unlike Capote, who was moving in their circles, former President Harry S. Truman was living quietly in Missouri with no involvement in either media or movies.

It is 1968 and Truman is summoned to his confidante Babe’s Fifth Avenue apartment, where she has discovered her husband, Bill (Treat Williams), scrubbing a giant bloodstain from her bed. Babe tearfully reveals the stain has nothing to do with her (she is menopausal, and in any case, “that part of our marriage has been over for years”); rather, it was left by Mrs. Nelson Rockefeller, nicknamed Happy, who knew the fastidious Babe would be more distressed by the damage to her sheets than the encroachment on her husband, whose numerous infidelities Babe had decided to put up with in return for their exquisite lifestyle.

This is based on an episode from Answered Prayers, the Proustian novel of his smart-set friends Capote was never able to finish, and the publication of excerpts from which in Esquire led to his ostracization by the ladies who lunch. In the story, Ina Coolbirth (the fictional equivalent of Babe’s best friend Slim) gleefully recounts an episode in which the Bill Paley equivalent “Dill” has an affair with “a cretinous Protestant size 40 who wears low-heeled shoes and lavender water.” She has sex with Dill in his wife’s bed but doesn’t tell him she is menstruating. “His whole paraphernalia had felt sticky and strange,” Ina overshares, “as though it were covered with blood. As it was. So was the bed. The sheets bloodied with stains the size of Brazil.”

Bill Paley’s serial infidelities were, like President John F. Kennedy’s, numerous and well-known (“he always had a roving eye and a groping hand,” said his old friend Irene Selznick), so this story may well have some basis in truth. However, the lady in question is unlikely to have been Happy Rockefeller. For one thing, Happy Rockefeller had had a long-standing affair with Nelson Rockefeller despite their both being married to other people and his being governor of New York. Happy Rockefeller (whose actual name was Margaretta Fitler) had, with her first husband, James Murphy, been neighbors of Nelson Rockefeller and his first wife in New York and also in Maine. They even built a home near the Rockefeller estate in Westchester, and the two families frequently socialized together. In 1958, while still Mrs. Murphy, she became a volunteer in Nelson Rockefeller’s first campaign for governor.

When the governor divorced his wife of 31 years to marry Happy in 1963, it caused the most enormous scandal and was widely thought to have tanked Rockefeller’s chances of winning the 1964 Republican nomination. Happy became a punchline for both amateur and professional comedians and, even worse, gave up custody of her four children shortly before her marriage to Rockefeller. Having sacrificed so much, it is highly unlikely she would risk further chaos for an affair with Bill Paley only five years later. The appearance of the Esquire excerpt in 1975, dredging up all this old scandal, would have been particularly hard on Rockefeller, who was recovering from a double mastectomy at the time.

In fairness, the Answered Prayers material does not mention Happy Rockefeller by name but merely refers to “the governor’s wife.” Laurence Leamer’s Capote’s Women, the source material for Feud, theorizes that the deceived husband was the former governor of New York, Averell Harriman, and the vengeful mistress his wife, Marie, another old-money aristocrat and an acquaintance of Capote’s.

Or the “governor’s wife” may have been an amalgamation of different Bill Paley girlfriends. What is very odd is that, having decided to identify “the governor’s wife” as Rockefeller, the show depicts her as rather zaftig and blowsy, complete with very 2024 pillowy lips, when the actual Happy was a rangy WASP who didn’t even dye her gray hair, much less resort to tweakments. More significantly, it’s possible to accept the petite Naomi Watts as elongated coat-hanger Babe, but it’s not possible to accept that Babe would refer to the perfume Mrs. Rockefeller wears, Calèche, as Cal-le-shay or that she would say her fine, now ruined linens (Porthault) were “Port hole.” We can accept dramatic license for a shorter Babe, but a Babe with a poor French accent? Never!

1975 sees Truman trying to persuade his editor that even though he has missed his third deadline for Answered Prayers and owes his publishers a $400,000 advance, “I will deliver one day. You know that.” However, instead of getting down to work, he gets (more) drunk and heads out to a bathhouse. There he meets a hunky stranger (Russell Tovey), who keeps going on about his insatiable need for sex, and the next thing we see he’s inviting his new, unbecomingly bridge-and-tunnel love interest who is called John O’Shea to meet the Swans for lunch at their regular haunt, La Côte Basque. (It does not go well.) On the subway home, John, whom Truman is thinking of making his business manager—very much against the Swans’ advice—urges Truman to write about the lunches. Their relationship becomes increasingly mutually abusive, with Truman using his viperous tongue to goad O’Shea into beating him up, with particularly ugly results at a Thanksgiving dinner at Joanne Carson’s house in Los Angeles.

According to Capote’s Women, Capote did indeed meet married bank manager John O’Shea in a bathhouse (although in 1973, not 1975), and their relationship became increasingly mutually abusive, with Capote provoking O’Shea into physically attacking him at a Thanksgiving dinner, but in Miami in 1981. In the documentary The Capote Tapes—a collection of interviews with those who knew the writer—O’Shea’s daughter Kerry Harrington describes the impact of the arrival of Capote into the lives of her “ordinary Irish Catholic family.” When O’Shea left the family to live with Capote, far from being upset, Harrington said, they were relieved. “My dad was a violent alcoholic and we were terrified of him,” she recalled, “so we felt incredibly grateful to Truman for taking him away.” Capote later virtually adopted Kerry and she became the inspiration for the main character in Answered Prayers, Kate McCloud.

At the height of his fame following the critical and commercial success of In Cold Blood, Truman plans a gala social occasion that will be the talk of the town, with him as the social arbiter. In the show, he hires the noted documentarians Albert and David Maysles to make a film about the planning process and the event itself. The Maysles interview all the Swans (each of whom Truman has led to believe will be the guest of honor) and shoot a planning lunch at La Côte Basque.

The entire third episode of Feud is shot as if using footage from a Maysles documentary (an homage from director Gus Van Sant). But no such documentary was ever commissioned, although Albert Maysles was a friend of Capote’s and did attend the actual ball. And if there had been a documentary in the works, La Côte Basque would no more have allowed cameras to shoot during lunch service than they would have added a Whopper with special sauce to the menu. The Maysles did, however, make a 30-minute documentary about Capote and the impact of In Cold Blood on the development of the nonfiction novel genre, called A Visit With Truman Capote.

After all his meticulous planning, Truman chooses his “favorite” Plaza dish, the chicken hash, to serve at the ball. The guests’ reaction, as captured by the Maysles’ camera, is not great. “What is this? It smells like a dead animal,” says Leland Hayward, Slim Keith’s ex, while his current spouse Pamela (formerly Churchill) observes, “Is this the option for supper? It looks like dog food.” Other guests appear similarly unimpressed.

This reaction is not necessarily untrue, but it is unlikely. Most of the guests would have been to dozens of balls at the Plaza and similar swanky hotels and would know not to expect a big sit-down meal but rather to eat beforehand at private dinner parties in guests’ apartments. It was traditional at a ball to serve a sort-of quasi-breakfast buffet at midnight to keep people from getting too drunk on an empty stomach.

For his buffet, Capote ordered the Plaza’s famous chicken fricassée (an elevated hash-like dish enriched with sherry, cream, and hollandaise sauce), plus spaghetti Bolognese, sausages, and scrambled eggs with anchovy crumb. It’s hard to believe people wouldn’t have found something in that midnight feast they wanted to eat. Plus, it’s very unlikely that Hayward would have dismissed the chicken dish out of hand: Pamela was known for cooking chicken hash on a hot plate when she and Leland were on the road, which suggests that far from thinking it smelled like a dead animal, it was also one of his favorite dishes.

The program does the ball a disservice in a couple of other ways. For example, it suggests the Swans were the big attraction of the guest list. They were a component, but what made the event so exciting for those who were there was the collision of worlds. As Robert Silvers, longtime editor of the New York Review of Books, said, “Truman had always had a fantasy of the grand world, the smart world, the literary world, each of which was in some ways precious to him. It was tremendously important to Truman to be a star in all of those worlds. The mixture of all those groups was so obviously an emanation of Truman’s dream.”

As a result, there were literary lions (like novelists Norman Mailer and John Fowles and poetess Marianne Moore); social grand dames like Brooke Astor and Alice Roosevelt Longworth (famous for the line “If you don’t have anything nice to say, come sit by me”); intellectual heavyweights like economist J.K. Galbraith; Old Hollywood icons like Merle Oberon and Tallulah Bankhead; and beautiful young things like Candice Bergen and Penelope Tree (the 16-year-old daughter of Babe’s oldest friend who became a top model as a result of her appearance at the ball). There was also theater producer Harold Prince, Andy Warhol, Cecil Beaton, director Gordon Parks (who quipped that he and his wife, along with novelist Ralph Ellison and Harry Belafonte, put the Black into the Black and White Ball), Henry Fonda, George Plimpton, and choreographer Jerry Robbins. Frank Sinatra was there with his age-inappropriate girlfriend Mia Farrow, as was Lauren Bacall—who owed her big break to Slim Keith, then married to director Howard Hawks, seeing her on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar and whose character in To Have and Have Not Hawks supposedly modeled on his wife. But in the episode, you get no sense of this actual concentration of beauty, brains, and talent.

The other thing about the ball’s presentation that seems oddly off is the music. What we hear are sort of snippets of 1940s-like big band music and some 1930s hot jazz. What the guests would have actually heard is smooth renditions of the Great American Songbook with added swing (the entire score of Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan captures the style). The actual music for the ball was provided by society bandleader Peter Duchin, who, in yet another demonstration of the incestuous nature of this world, was the unofficial foster son of Bill Paley’s inamorata Marie Harriman, who took him in after his mother died. Duchin later went on to marry Slim Keith’s stepdaughter, Brooke.

Despite very strict door security, a ghost at the feast manages to sneak in—Ann Woodward (Demi Moore), the former radio actress who married a banking heir, who was later found shot in his own home in 1955. Woodward said she had shot her husband thinking he was an intruder. The death was ruled accidental, but in Woodward’s social circle of society, the rumor circulated that she shot him on purpose because he was planning to divorce her, and the deceased’s mother had used her considerable local influence to hush the whole thing up. However, Woodward was never indicted for the shooting, and later, a man named Paul Wirths came forward to say he’d attempted to break into the Woodwards’ house on the night in question, essentially corroborating Ann’s version of events. This didn’t stop Capote from repeating the original, thinly veiled slur in the 1975 excerpt of Answered Prayers, a dredging-up that likely contributed to her suicide.

While the general outlines of Woodward’s case, ostracism, and death are true, the Black and White Ball confrontation seems to be pure invention. There is no evidence that Ann Woodward crashed the event, with or without her son. There were, however, three crashers who did get in. One, a young woman named Susan Payson, happened to already be wearing a ballgown and simply walked in with her escort, whereupon they encountered the host. “Oh, yes,” she recalled Capote saying, “I don’t remember where you’re sitting, but why don’t you come to this table … These are my friends from Kansas.’” She soon realized the “friends from Kansas” were several of Capote’s sources for In Cold Blood, whom he had flown in from Kansas just so they could attend the party.