What’s Fact and What’s Fiction in The Crown Season 6 Part 2

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the final episode of The Crown, Prince William is having tea with his grandmother and, in the course of discussing her proposed Golden Jubilee celebrations, brings up how much he dislikes the widespread press suggestions that the crown should skip a generation and go directly to him, bypassing Prince Charles. He and the queen agree that this is a ridiculous idea.

However, the series itself seems to take this approach in its last episodes, focusing on William—his bond with his grandmother; his recovery from his mother’s sudden, tragic accident; his growing romance with Kate Middleton; and his coming to terms with his destiny—while Prince Charles barely features.

As the series has gone on, it has become less grounded in the historical realities of the monarchy—the balance between the crown and government, the struggle to maintain the institution’s relevance, and the role the queen has played in various historical crises—and more about relationships and personal turmoil, necessarily depending more on imagined conversations behind closed doors. It has, like the monarchy itself, become more soap opera–ish, never more than in the first part of the final season, which dealt with Princess Diana’s death.

While the substance of private conversations is impossible to verify, we nevertheless try to separate what’s fact and what’s fiction in the actual events depicted.

During his first term at the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland, William is hanging out with a group of buddies when Kate Middleton walks by and they all stop talking to watch. Even though William is besieged on the streets by gangs of screaming teenage girls as if he were a Beatle in the 1960s, they tell him he doesn’t have much of a chance because Kate has been dubbed the “fittest” (in the British sense of hot) girl at St. Andrews.

While we don’t know if this bro-ish conversation ever took place, according to Middleton biographer Katie Nicholl, by the end of freshman orientation week Kate had been given the nickname “Beautiful Kate” by her friends and was later voted the prettiest girl in St. Salvator’s, the large dorm both she and William were assigned to in their first year. Prior to that, a friend from Marlborough, the prep school she attended as a teenager, told the Daily Mail that once Kate lost her braces and gained some weight, she was apparently top of the “Fit List,” a ranking the male pupils would sometimes pin on the walls. More significantly, the school yearbook voted her “Person Most Likely to Be Loved by Everybody.”

At one of the first parties he attends at St. Andrews, William meets a posh girl who rejoices in the name of Lola Airedale-Cavendish-Kincaid and has a hot romance with her before she, realizing that William has a crush on Kate, breaks up with him. (Kate is from the moneyed upper middle class but is not an aristocrat.)

Lola is an invention, but before dating Kate, William did go out with a posh girl named Carly Massy-Birch. However, unlike the rather theatrical and boho Lola, Massy-Birch was a down-to-earth country girl who, according to Nicholl, was happy to stay in and cook for him. They broke up not because of William’s interest in Kate but because of his lingering interest in a girl he’d had a passionate summer romance with before going up to St. Andrews. This was Arabella Musgrave, part of his polo crowd, whom he had known since they were both little.

The show also depicts Kate as having a somewhat serious boyfriend before William, a law student named Rupert Finch. During her first year, she did in fact go out with a law student named Rupert Finch, who was, by our reckoning, as handsome as his film counterpart.

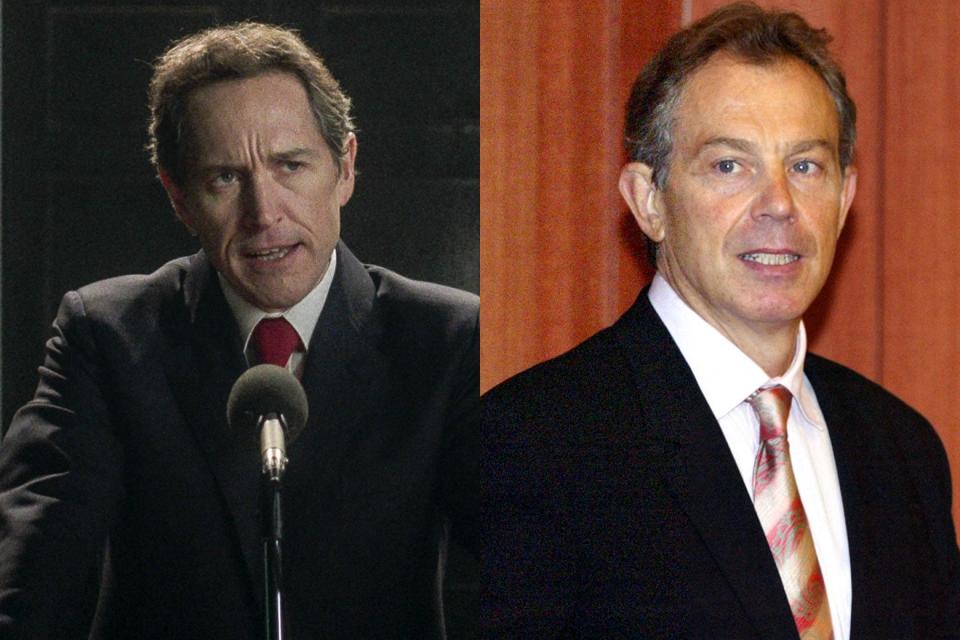

In 1999, realizing that her young prime minister, Tony Blair, had a 66 percent approval rating, far higher than the monarchy’s, the queen wonders whether the crown couldn’t do with some modernizing. Her private secretary, Robin Janvrin, commissions some focus groups. The findings are grim: 54 percent of respondents think the monarchy is wasting public money, 69 percent say it’s out of touch, and only 10 percent think it should continue in its present form. Although Blair is far from her favorite prime minister, she asks him for advice. After consulting with his wife, Cherie (a committed anti-monarchist), he comes up with several suggestions, including abolishing the rule that when it comes to inheriting the throne, the eldest boy takes precedence over an elder sister and that people in the line of succession can’t marry Catholics. He also raises questions of constitutional significance, like whether the monarch should still be the commander in chief of the armed forces and be able to dissolve Parliament. But what really gets the queen’s goat is when he proposes a “bonfire of the sinecures,” abolishing the trappings of pomp and circumstance, like the Maltravers Herald Extraordinary, the queen’s Herb Strewer, and the Warden of the Swans (all actual jobs in the royal household). On interviewing the holders of these positions, she comes to the conclusion that they represent a wealth of knowledge and expertise, telling Blair she will not be getting rid of them because “tradition is our strength.”

Showrunner Peter Morgan is in something of a pickle, having explored the Blair-queen relationship in depth in his 2006 film The Queen (set in the aftermath of Diana’s death) and trying not to repeat himself. We can find no evidence of the royal household commissioning focus groups, but the contents of the queen’s audiences with her prime ministers are confidential, and if there was such a modernization study, it would probably be classified until 2029. However, in 2011, David Cameron, who became prime minister in 2020 (Blair left in 2007), put forward a bill that said female members of the royal family have the same rights of succession to the throne as men and abolished the rule that says that anyone who marries a Roman Catholic can’t become monarch. The Warden of the Swans and the Maltravers Herald Extraordinary are still there, but King Charles has made no secret of the fact that he wants to slim down the royal family to core members and reduce the size of the royal household.

In a flashback, Princess Margaret suggests to her sister that they join the crowds in front of Buckingham Palace celebrating, to put it mildly, the end of the war in Europe. Elizabeth uncharacteristically agrees to this breach of protocol, and the two princesses, accompanied by a young Lord Porchester and Royal Equerry Peter Townsend, sneak out through a side entrance. The quartet decide to go to the Ritz hotel, where Elizabeth follows a Black GI into a basement lounge in which several American GIs are jitterbugging with British girls, and the incognito princess joins in. Meanwhile, Margaret and the escorts are drinking champagne in the more sedate lobby until they notice that Elizabeth is missing and join her in the nightclub. The two princesses return to the palace at dawn.

This is partially true. The two teenage princesses did join the throngs celebrating in front of the palace, an event the queen called “one of the most memorable nights of my life.” However, they did not sneak out (as if!) but asked the permission of their parents, who granted it as long as the girls were accompanied by 16 trustworthy members of the royal household (these included Porchester and Townsend). As Jean Woodroffe, the Queen’s lady-in-waiting and one of the party, recalled, “We went out of one of the back doors of Buckingham Palace and headed up to the left of the Mall. There were lots of people singing and shouting,” while Margaret Rhodes, the queen’s cousin and another member of the group, said, “For some reason, we decided to go in the front door of the Ritz and do the conga. The Ritz has always been so stuffy and formal—we rather electrified the stuffy individuals inside. I don’t think people realized who was among the party—I think they thought it was just a group of drunk young people.” So the queen did indulge in some lively public dancing, but not doing the jitterbug with young men, as depicted in the film.

During the war, the Ritz did have a basement bar called the Pink Sink, but far from modeling itself on Harlem’s Savoy Ballroom, as the show suggests, it was a hub of London’s wartime gay culture and, not coincidentally, a mecca for spies. There would have been a lot of single men celebrating there, but they likely would not have been interested in dancing with Princess Elizabeth.

The princesses did not arrive home at dawn but were back by midnight, in time to see the king and queen make a second appearance on the Buckingham Palace balcony. In a 1985 interview with the BBC, the queen recalled that they “were successful in seeing my parents on the balcony, having cheated slightly by sending a message into the house, to say we were waiting outside.”

Finally, as Princess Margaret was 14 when the war ended, it is highly unlikely the Ritz would have served her champagne. Also, it is a lot less creepy that Peter Townsend, the same man she had to give up to remain in the royal family, was part of a large group rather than out on a date with a 14-year-old who later fell madly in love with him.

The show suggests that ever since William’s glance lingered on a young teen Kate when she and her mother encountered William and his mother selling the Big Issue in London’s Canary Wharf financial district as part of a Christmas fundraising effort, Carole Middleton thought her daughter should aim high. (The Big Issue is a magazine that raises money for the homeless, who act as street vendors.) When Carole pushes Kate to break up with Rupert Finch because William is single again, Kate finally pushes back. She informs Carole that she went to St. Andrews only because her mother suggested it, even though she was all set to go to Edinburgh University with some school friends. And it was Carole who sent Kate on a gap-year expedition to Chile sponsored by Raleigh International, the same program William was on that same summer (though they hadn’t met at the time).

The source for this view of Carole Middleton as a sort of modern-day Mrs. Bennet, pushing her pretty daughter in front of a highly eligible bachelor, is Tina Brown’s The Palace Papers. According to Brown, Middleton sent Kate to a country prep school near the family home in Berkshire, which was also conveniently close to Eton, the elite school William attended. Brown suggests that Middleton’s first glimpse of her future husband was not in Canary Wharf but when he attended a hockey match against her school when he was 9.

William and Diana never sold the Big Issue together, in Canary Wharf or anywhere else. Diana, a supporter of charities for the homeless, frequently bought the magazine, as vendor Frank McGucken, whose pitch was near Kensington Palace, where the princess and her sons lived, confirmed: “Lady Diana used to come to me, privately, on her own, and buy the paper.” William, who has continued his mother’s work with the same charities, did sell the Big Issue for a day … but in June 2022, as part of his own 40th birthday celebrations.

Kate had planned to go to Edinburgh University, where her two best friends from boarding school had also applied. However, despite being accepted, she pulled out at the last minute and reapplied to the smaller, more remote St. Andrews, even though, as two of Kate’s former tutors confirmed to author Nicholl, Edinburgh had been her first choice.

The real-world chronology suggests that Kate’s romance with William was not the result of her (or her mother’s) machinations to ensnare him but rather evolved organically. It is true, as the show depicts, that William moved Kate out of the friend zone when, during his second term, he attended a student fashion show in which she modeled the famous see-through dress.

The Crown has him confessing his feelings at a party after the fashion show, with Kate reciprocating before the two share their first kiss. But those who were there say flames failed to ignite immediately, not least because Kate was still involved with Finch. “It was clear to us that William was smitten with Kate,” one friend said. “He actually told her she was a knockout that night, which caused her to blush. Kate had really made an impression on William. She played it very cool, and at one point when William seemed to lean in to kiss her, she pulled away. She didn’t want to give off the wrong impression or make it too easy for Will.” The two would initially remain friends.

When William moved into an apartment on Hope Street with Kate and two other students at the start of his second year, it was not initially a love nest, as The Crown suggests. But somewhere along the way after setting up house, the two became more than just flatmates, and the rest is history.