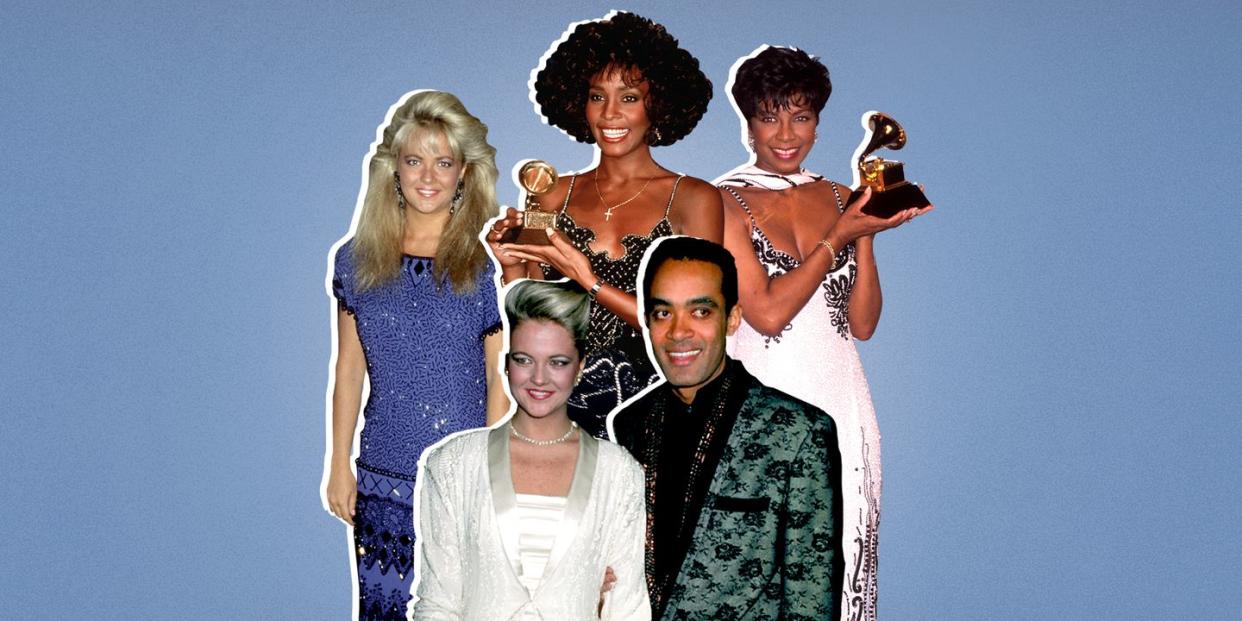

Fabrice's Lavish Beaded Dresses Defined '80s Party Culture. It's Time He Got His Due.

Fashion, for certain women of style in the 1980s, was flashy, over-the-top, and ultra-glamorous. Their party dresses were carpeted with sequins and bugle beads, evening gowns dripping in embroidery. The gilded decade’s look is unforgettable, and yet somehow, one of the forces that shaped it—the once-famous Fabrice—has all but faded into obscurity.

From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, Haitian-born American fashion designer Fabrice Simon (known professionally as Fabrice) cut an embroidered swath through the fabric of high society and celebrity fashion. At one time, everyone knew his name. A week after he passed away of AIDS at only 47 years old on July 29, 1998, the New York Times reported the news of his death a, giving him a substantial two-column quarter-page tribute.

But what happened to his legacy after that remains a mystery. If you ask anyone who knew him—friends, former clients, or '80s fashion insiders—why there’s almost no recognition for his work over the last 22 years, invariably their answers begin with a solemn, “I just don’t know.”

Perhaps the answer lies somewhere between fact and fashion. For an industry that has long celebrated its design superstars with elaborate solo and group exhibitions, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Costume Institute’s The World of Balenciaga in 1973 and Charles James: Beyond Fashion in 2014 to those with more off-the-wall themes like its last costume presentation, Camp: Notes on Fashion in 2019, it can often be incredibly harsh to designers who, by all account, should have made the cut.

Born January 29, 1951, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Fabrice was 13-years old when his parents moved with him, his brother, and his sister to New York in 1964. His father was an accountant and his mother a seamstress—an occupation Fabrice was taken with. “It’s how Fabrice learned to sew,” recalls his sister Brigitte Steibel. “I remember as a little girl, he’d be watching our mother sew other people dresses—when we first came to the United States she worked for Geoffrey Beene.”

As his mother helped make a living to support the family, he graduated from Flushing High School in Queens, and got a job with the fabrics house United Merchants and Manufacturers, where he was encouraged to study textile design. He would spend a semester at Fashion Institute of Technology before going back to the company for five years, designing fabrics for clothing and wallpaper.

But by 1976, Fabrice was tired of making fabrics for others to fashion. That year, he made dresses with his own prints: painted or airbrushed patterns on silk, a sort of predecessor to the beaded looks he’d make his name with. “He just decided he wanted to design,” Steibel remembers. “If people have those still, they’re surely collector’s items.”

The 25-year-old fledgling designer was quickly picked up by Henri Bendel, which had a program for displaying emerging talent. (The storied department store continued to carry his clothing into the early '90s.) With his foot in the door of the fashion industry, Fabrice began experimenting with beadwork in 1980; a year later, he’d receive a special Coty Award for his beaded designs.

“He really got into it—it brought out all his creativity,” says Steibel. He first stenciled his designs onto the fabric, which he then sent it off to Haiti where the beadwork was done by hand in a factory that was overseen by his parents. It was shipped back to New York to be assembled. “Our Caribbean and Haitian heritage really influenced him. Not many people realized it, but there were a lot of voodoo symbols incorporated into the beadwork.”

Some did, though: In 1984, Shirley MacLaine wore Fabrice when she won both the Academy Award and Golden Globe for Terms of Endearment and “People began to say wearing Fabrice [to an awards presentation] brings you good luck,” Steibel laughs.

All the best upscale department stores and boutiques eventually carried Fabrice designs—Bergdorf Goodman, Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, Bonwit Teller, Barney’s, Maxfield LA, and Martha among others. Usually his collections consisted of about 30 looks, most pieces selling for between $2,000 and $3,000.

“I considered him a couturier,” says top '80s model Dianne DeWitt, who worked with everyone from James Galanos and Bill Blass to Yves Saint Laurent. “I modeled for him several times in the early '80s, and he used the most beautiful fabrics and really made the most of the female body. Though I never got to know him intimately, his clothes were always so special, as was his clientele.”

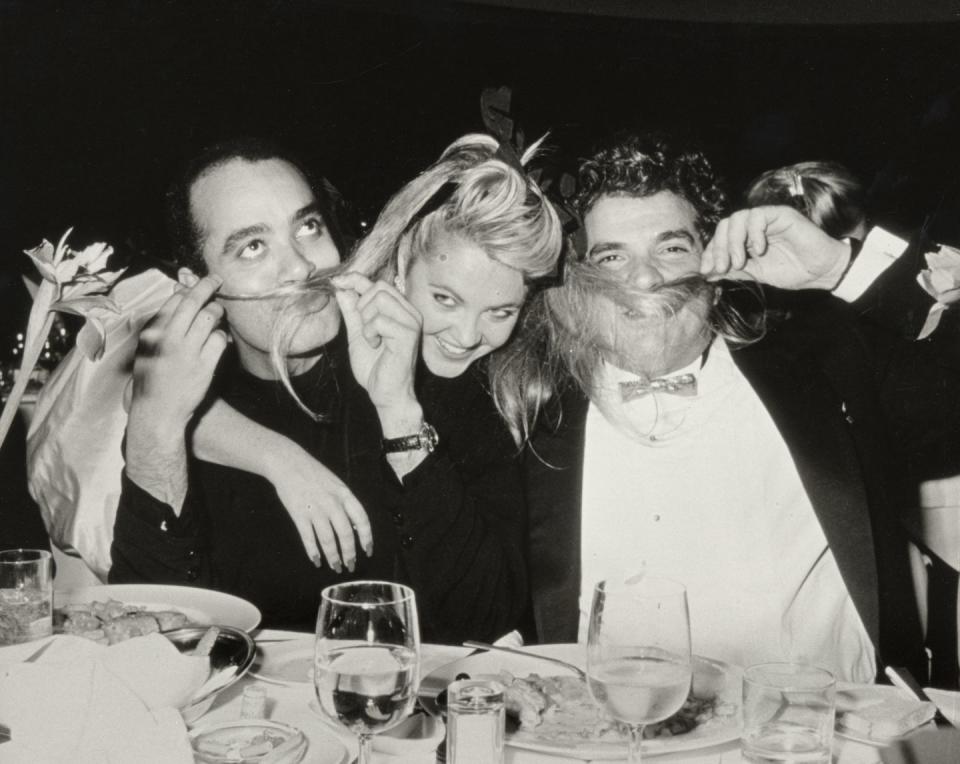

Through a chance meeting, likely in early 1981, Fabrice was introduced to Cornelia Guest, daughter of socialite and fashion icon C.Z. Guest. The 18-year-old debutante—later named Deb of the Decade—and the 30-year old designer became fast friends. “I first met Fabrice at his atelier with [fashion writer and columnist] Eugenia Sheppard,” says Guest. “She took me over and it was the most beautiful atelier, and he was the most handsome, adorable, fun man—I had more fun with Fabrice, I can’t even tell you!”

While Carolina Herrera would design Guest’s formal coming out dress, the dress she wore for the party her parents' hosted was by Fabrice. “He designed this short dark blue dress with black and silver beads. It was absolutely beautiful, but people were just horrified—when you come out at home, you’re supposed to wear white, and I didn’t,” she says. “But Fabrice and I were so happy we danced all night.”

For the better part of the decade, the pair were practically cinched at the waist, hitting New York hotspots like Studio 54 or jetting off to Palm Beach, as Guest wore dozens of his creations.

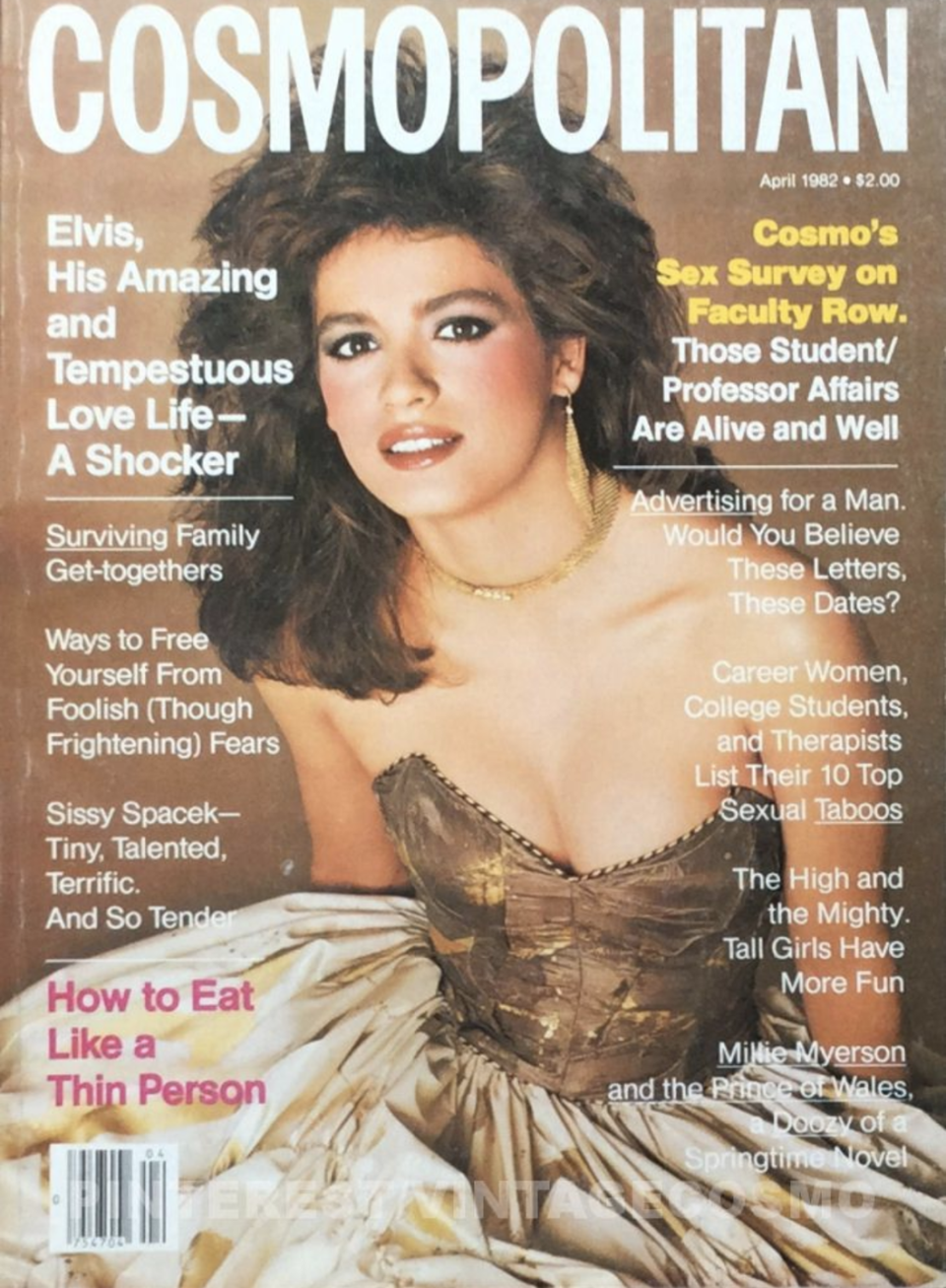

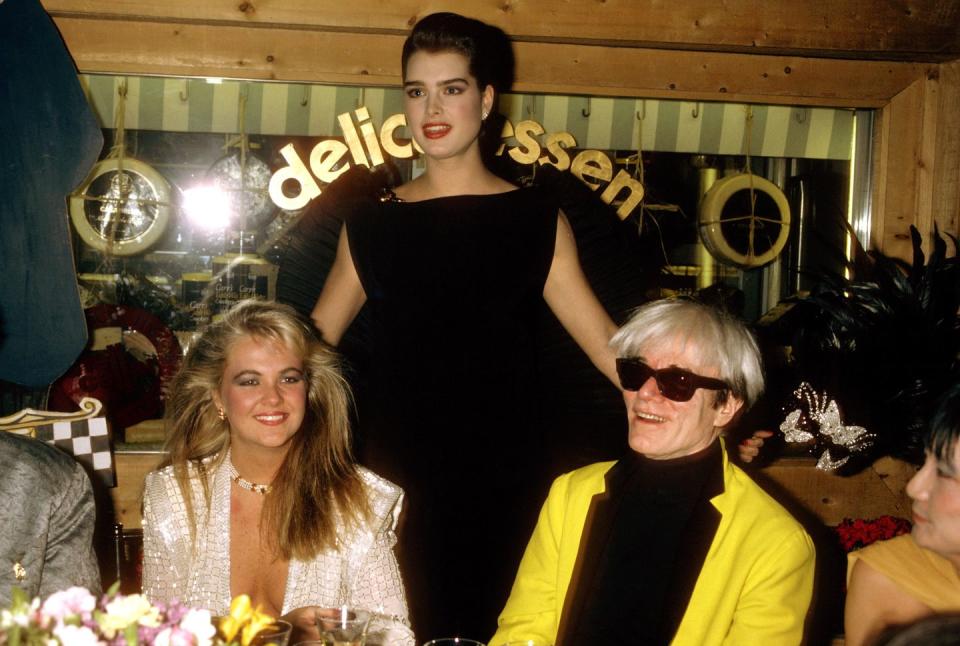

In addition to socialites like Guest, Fabrice won over the industry elite. He was a favorite of fashion photographer Francesco Scavullo and his partner Sean Burns. Scavullo regularly pulled the designer’s clothes for shoots in the early 80s, including several Cosmopolitan covers with models like Lisa Cummins, Brooke Shields, Paulina Porizkova, and Gia Carangi, who wore Fabrice in what would be her final cover shoot in April 1982. Cosmo’s legendary editor-in-chief Helen Gurley Brown told the Toronto Sun in 1987 that the “most perfect dress in my wardrobe, and I will keep like a jewel forever, is made by Fabrice.”

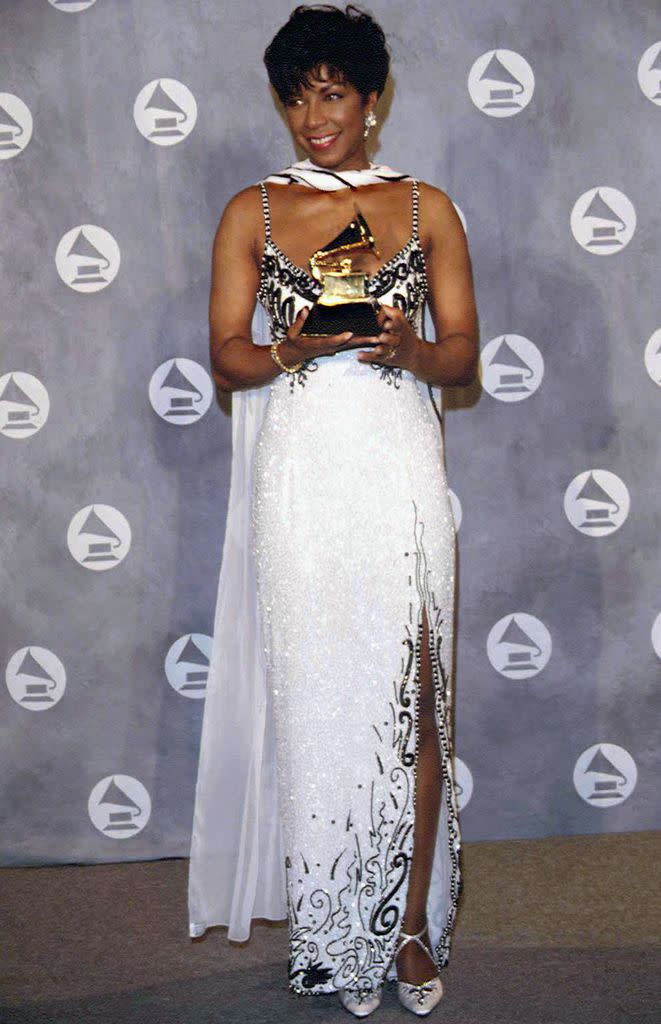

The couturier's clientele included the likes of fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert, Nina Griscom, Anne Douglas, Veronique Peck, Cicely Tyson, Rita Moreno, Whitney Houston, Iman, Peter Allen, Luther Vandross, Anita Baker, Roberta Flack, Kathleen Turner, Morgan Fairchild, Elizabeth Taylor, and Natalie Cole. For Cole’s 1991 Unforgettable tour, Fabrice designed the singer’s entire wardrobe.

Flack, the five-time Grammy Award-winning singer wore Fabrice regularly, including for the cover of the record she released with Peabo Bryson in 1980 and her 1984 Greatest Hits album. “Fabrice was a beautiful and talented designer—I loved how provocative and innovative his designs were,” she told T&C in a rare interview for this story. “I wore his gowns not only for these album covers, but in my performances as well. His dresses were worn by the most glamorous women of his time [and] he set the pace for the ‘After 5’ fashion designers.”

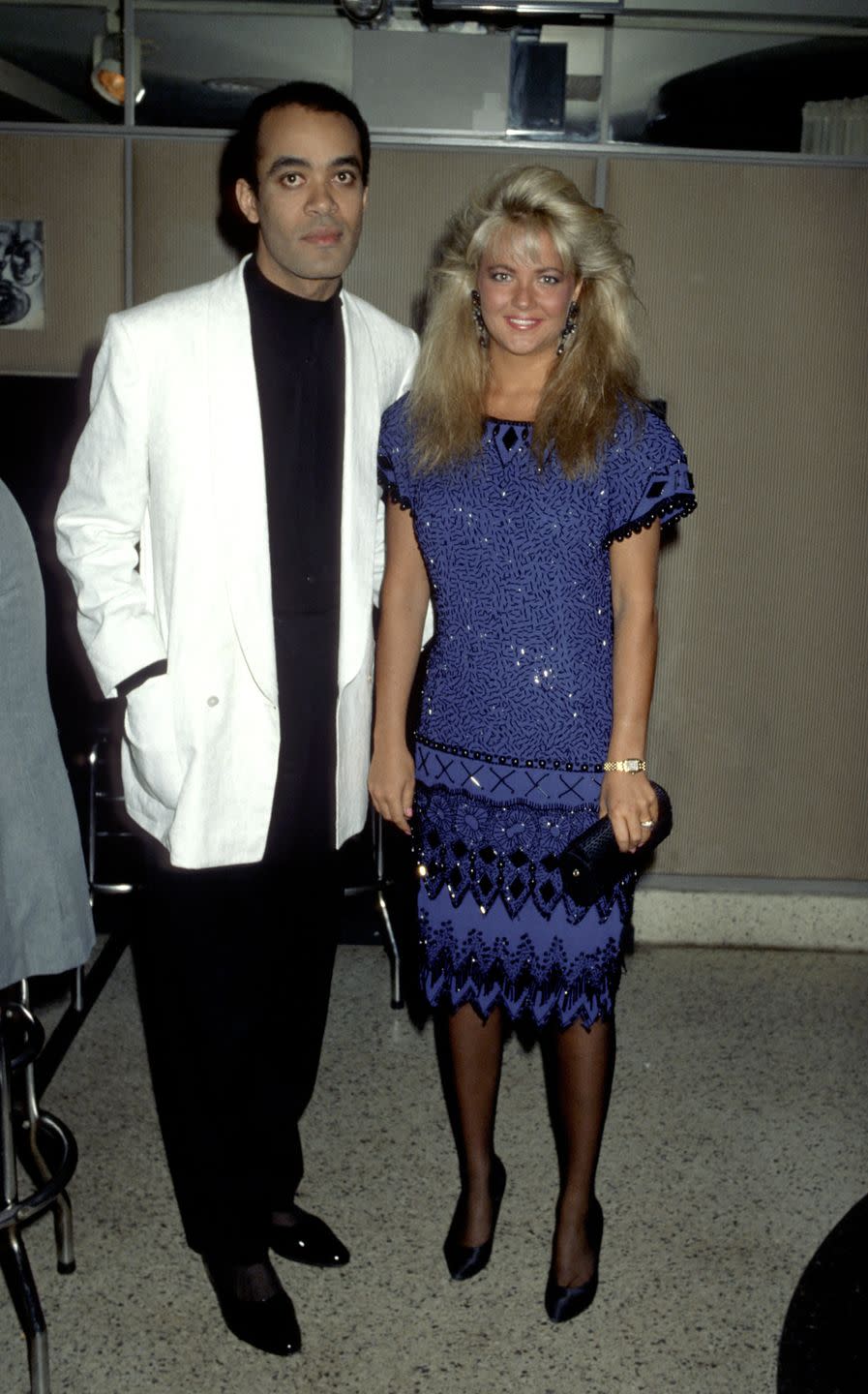

Fairchild fell for his designs on set. “I think the first time I came across Fabrice I was [being shot for] a photo layout for Harper’s Bazaar,” the actress says. “They put me in several of his things and I fell in love.” Fairchild became a devoted client, wearing Fabrice in 1985’s televised charity performance, Night of 100 Stars—walking the show’s fashion parade in a long cream beaded evening gown, with the designer on her arm. “I’m such a girl, I love anything that glitters and he was so great at that.”

She again wore Fabrice to the 1990 program, this time a shorter, slinkier cocktail dress. “I bought a bunch of stuff from his showroom,” she adds. “He kept my measurements so all I had to do was call him up, order anything, and he’d make it.”

Kathleen Turner recalls the Fabrice design she wore when she hosted the Tony Awards in 1990—the same year she was nominated for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. “The dress I wore—oh my god it was beautiful—and heavy, I don’t know how much it weighed,” she laughs. “I remember the week leading up to the Tony’s and he wanted me in for fittings every single day, but I was doing eight shows a week!” Turner also recalls a red satin evening suit with an embroidered collar she wore several times. “Honestly, I was always thrilled with what he made me—they were all like pieces of art… like paintings with beads.”

Throughout the majority of the '80s—until the stock market took a nosedive in 1987—Fabrice created both custom pieces and ready-to-wear garments, and would infrequently present his collections for small audiences at venues like the Pierre in New York. “I remember attending the last presentation at the Pierre in 1987,” says close friend Patrick McDonald, who would soon become Fabrice’s Director of Couture. “Garren did all the hair [for the models] and I remember Mounia walked in that show—I met Iman [for the first time] with him.”

McDonald met the designer years earlier while working as a manager at Barney’s, and had seen him around Studio 54. In 1988, McDonald began to work for Fabrice, whose business by this point consisted solely of private clients (though the designer did later partner with Herb Rounick on a short-lived diffusion line called Fabrice Silhouette). “We were located at 530 7th Avenue before moving up to the New York Gallery Building on West 57th Street,” he recalls. “We had a space right up front with little balconies—it was a fabulous. Then he got sick.”

Around the time he was moving into his new showroom in the New York Gallery Building, Fabrice was admitted to New York Hospital with serious AIDS-related health issues. “He was very ill and was in the hospital for about eight weeks in 1993, and off-and-on in 1994 when he finally closed,” recalls McDonald who visited him daily. “He had been very quiet about [his illness]. He didn’t even talk about it with me, and we were very close—but I think he knew a long time before.”

His staff had only settled in the new space for a few months when Fabrice announced he would be closing. “A lot of the ladies had worked for him for many, many years—there were a lot of tears,” says McDonald. For the private clients and personal shoppers with whom Fabrice worked, the abrupt closing also came as a shock, according to McDonald. “They were upset and surprised, and curious as to why. I think we just told them it was so he could pursue other things—like his artwork.”

Sometime in early 1998, Fabrice gave up his rented apartment on Lafayette Street, across from the NoHo Star, and moved in temporarily with his friend, designer Michael Katz, while he looked for an apartment to buy. “He’d even talked about moving to Paris at one point and asked if I would go with him,” remembers McDonald. “The night before he died, I took him out for dinner to Cafeteria in Chelsea, across from Barney’s. Afterward we went back to Michael’s and I was there until about one o’clock in the morning. I was shocked the next morning when I got the call—we were together just seven hours earlier.”

For most people in the fashion industry—apart from close friends and family—Fabrice faded into a distant memory. Looking through the Met’s online collection database, there are only three Fabrice pieces cataloged, all donated by the same client, Jamie de Roy, in 1999. The Museum at FIT, where he studied textile design, has only one, as does the Museum of Fine Art Houston. “I offered them several more when they came to my house, but they only took three—and one of them was a one-of-a-kind sample,” say de Roy, now a seven-time Tony Award-winning Broadway producer. “I remember being shocked they didn’t take a few things including a pink dress with black beading and a zigzag hem, and a fully-beaded black top and fitted skirt.”

“I think it’s sad,” says Fern Mallis, former executive director of the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), about the lack of representation in museum collections. “It’s a missed opportunity to properly document [fashion] history—and his history. He was out there, he had a successful business, but he never got that kind of respect from the fashion community.”

Mallis goes on to speculate why his work didn’t resonate, historically, in the same way that Halston’s did, for instance. “For me, I think he was like a Black Bob Mackie,” she continues. “Fabrice’s clothing was very party-driven, sexy and flamboyant. It’s just like Bob, who I think finally learned to live with [the lack of recognition].”

“I can’t pinpoint it,” adds McDonald about the designer’s lost history. “I think at the time it was all about Bill [Blass], Oscar [de la Renta], and Geoffrey [Beene]. He got press—not tons—and was still very successful, but he also didn’t play the game.”

Guest can’t imagine why a designer of his prestige would fade so quickly. “Everybody loved his clothes,” she says. “People like Scavullo and Sean Burns—who discovered [fashion designer] Zoran, and Miss Martha who launched the careers of more designers, they all loved Fabrice. It’s just so strange.”

“My brother loved what he did, but didn’t get the recognition he deserved,” laments Steibel. “He loved the fashion world and all its glamour. I remember days when photographers for the New York Post and others would be standing downstairs waiting for stars to come up to Fabrice for their fittings. For a long time, I tried to do something so that he’d be remembered—but I’m not in the fashion business anymore.”

There may be no single answer why his work has been overlooked for decades. But to rectify this misstep, it’s up to the industry’s educators, historians, and curators begin to recognize his contributions to American fashion—and to communicate in their curriculum, texts, and exhibitions. Then, he may start to get the recognition he deserves.

You Might Also Like