Their FA In Yosemite Was Renamed, Retro-bolted And Credited To Another Team

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared on Climbing

I always knew I wanted to be a climber. I grew up reading all the classic and crazy tales from Mallory to Whymper. The old Everest, Annapurna, Eiger and Matterhorn books filled my bookshelf alongside The Cat in the Hat and The Hardy Boys' House on the Cliff. One day my life would combine them all: The Mystery of the K2 Feline.

In high school, with wild and grandiose dreams about big mountains and first ascents, I put a plan together: Hitchhike to Yosemite and climb the biggest wall I could find. How hard can it be?

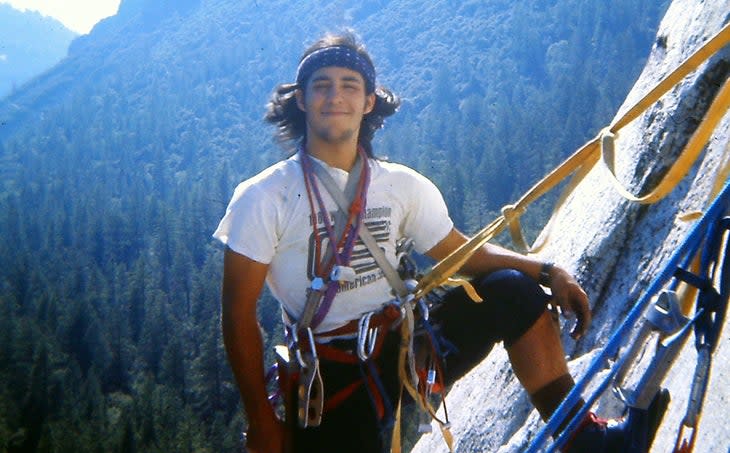

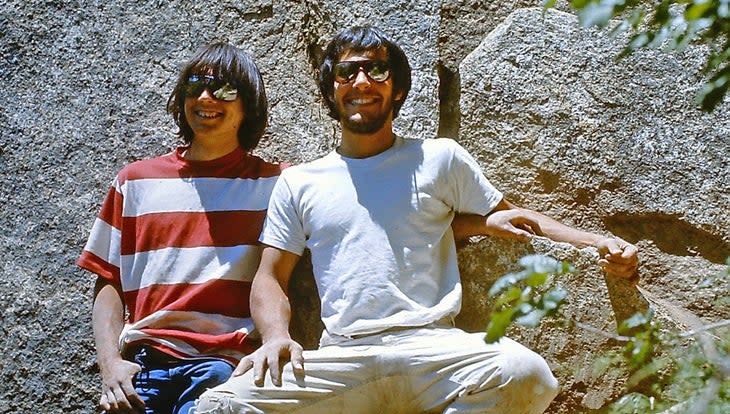

So that's what I did. In 1971, at 19, I arrived at Camp 4 when it was a dirty, dusty collection of faded-orange Sierra Design tents covered with battered canvas tarps liberated from construction sites. I set up my matching battered tent and trotted off to meet the local climbers. By the end of that summer I had established myself as the go-to kid if you needed someone to lead some heinous 5.10 offwidth pitch since, for some reason, I not only was able to squeeze into these punishing cracks, but I actually enjoyed them.

I returned to Yosemite every summer for the next few years, honing my skills, elbowing up nasty offwidths, and cooking big batches of Sunday pancakes in Camp 4. I seemed to have just the right body size (small) to feel at home in the narrow fissures that repelled the bigger boys, so I was sought out when a route included a crack between eight and 18 inches. For this was the age of crack climbing. If you weren't a crack climber, you were nothing. Face? Blah. Friction? Ugh. Chimneys? Phooey. Nope, unless it tore your knuckles and ripped at your wrists, it wasn't worth doing. Standard equipment on every climb was a big roll of white tape; getting ready for a crack climb was like taping up for a boxing match.

In 1977, I returned to tackle bigger ambitions. My plan for the spring was three big walls including the Direct NW Face of Half Dome; the West Face of El Cap, where I wanted to free climb as much as possible; and the North America Wall on El Cap with my long-time climbing mate Mark Hudon.

"If a drop of water falls from the summit of a great mountain to the ground, that is the route I want to follow." That was the kind of route I wanted to do.

To get ready for the longer routes I had to broaden my skills. Even though I could monkey my way up most offwidths, and even struggle up a thorny finger crack, I wasn't much of a face climber and knew it.

I started with a couple of lengthy face climbs on the Glacier Point Apron, long disdained as the baby beach of Yosemite climbing. I guess the joy of a dozen gloriously smooth pitches of polished granite in the early spring sun just didn't appeal to the denizens of the dark corners of Camp 4.

At the time I happened to be reading the biography of Walter Bonatti, an Italian mountaineer with more gripping first ascents than almost anyone at the time. He quoted an obscure aphorism attributed to his fellow Italian Emilio Comici that went something like this: "If a drop of water falls from the summit of a great mountain to the ground, that is the route I want to follow." That was the kind of route I wanted to do.

While scampering up the Goodrich route to the Oasis (a grassy, debris-strewn ledge a thousand feet up) on the Apron one afternoon with my buddy Scott Woodruff, with whom I was planning on climbing the West Face of El Cap, I had an epiphany: This was the perfect setting for my own "water drop" route. A black water streak descended straight down from top to the ground. Direct. Water, falling from the summit to the earth. My line.

"Scott," I announced, "we gotta climb this line. It's calling us. Listen! The sirens of The Yosemite Odyssey want us to join them. We must go … up!"

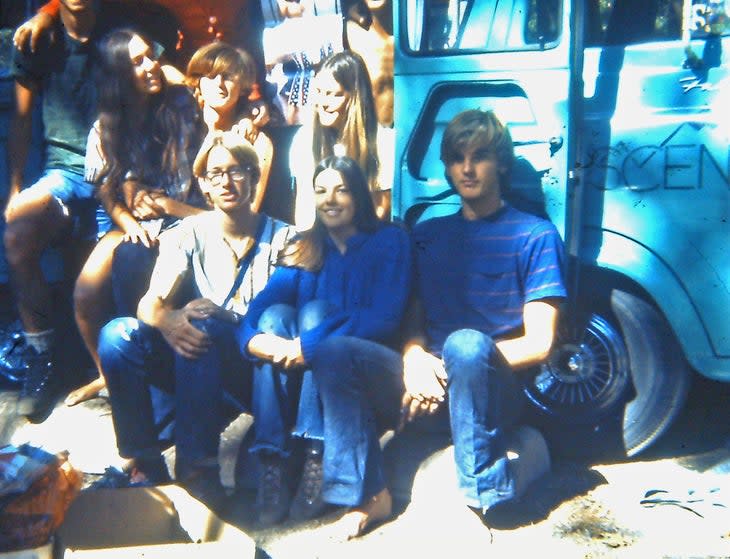

The 1970s in Yosemite were the heady era of the StoneMasters, the flock of elite rock jocks who held court on all things climbing, (self) named for their affinity for both the rock climbing and the evening smoke-a-thons that might continue well into the next day. These guys were good climbers--no doubt--but they also carried an air of superiority and condescension. They were the "in crowd" and made sure everyone in Camp 4 was aware of the fact. I got along with most of them individually; in a group they tended to be a bit more bellicose.

Announcing that you were about to embark on a new route in Yosemite was like declaring your intention of running for President, and the "masters" usually got wind of it pretty quickly. Depending on the route's location and their mood, they either decided to ignore you or run you out of the Valley. So I kept my modest plans to myself and a few cohorts.

Sometime around 1973 three of the early StoneMasters completed a difficult and dandy route they named Stoner's Highway. I had always thought that name a bit pretentious but suddenly it presented a sublime opportunity. Like Comici, I had a revelation: I would become head of the HoseMasters, and we would create the most bad-ass route imaginable, calling it Hoser's Highway. Ha! Take that!

Back in camp I rounded up my usual suspects--a ragtag group of climbing bums from Colorado and points west.

"Hey, I've got a great idea. Let's do a new route on the Apron. Who's in?"

The response was predictable: a blank stare, then a hearty round of laughter.

Also Read: Fluid Machine: Life, Death and Transformation on Sao Tome’s Pico Cao Grande

"No, wait," I implored. "I mean it. I found this line. Looks to be around 10 pitches. Straight up, and I mean straight. Fun! Big fun! Scott is in. Who else?"

A few members of our troop thought the prospect of a new route on the Apron "interesting," but not really worthy of their attention. A couple even scoffed at the idea, preferring to hang on the outskirts of Camp 4, hoping to catch a glimpse of Bridwell or Kauk heading somewhere important. Two others, having nothing better on their plates, decided to join us. So now we were four. The HoseMasters!

At the base of the rock the next morning I announced the rules:

1. We would each lead a pitch per day. The route must follow the black streak pretty much exactly. No one was allowed to deviate more than five feet to one side or the other.

2. Each leader would only be allowed to carry three bolts, two drills and a hammer. The leader could decide where on his lead to place his one protection bolt; the other two were for the belay. After all, we were on a budget, and bolts cost a couple bucks each.

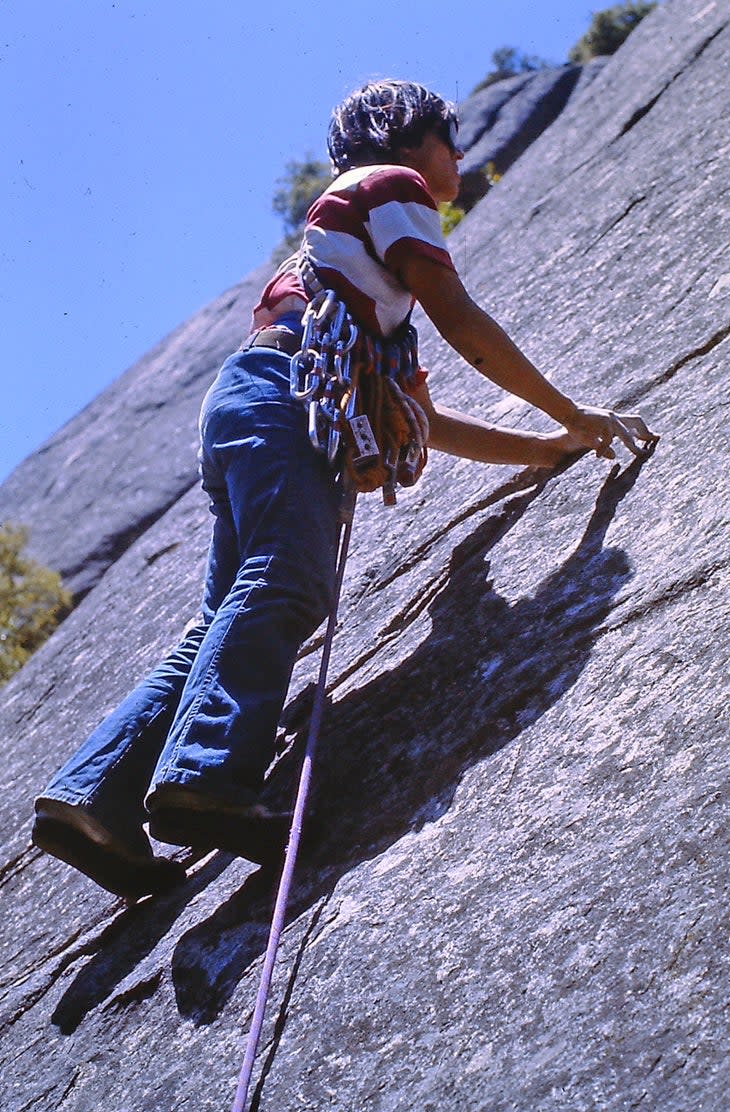

Besides, this was way before the era of rap bolting. Virtually all free-climbing protection was placed on the lead, and it usually wasn't easy. Indeed, it made many climbs at least one grade harder. To put in a bolt on the lead of a 5.10 friction/face climb meant smearing yourself to the rock with only your feet as you spent the next 15 minutes with a twist drill in one hand and a hammer in the other, pounding and twisting while trying not to fly off into space.

There was no "If you ain't flying, you ain't trying" mentality. Rather, it was, "If you're flying, you're dying."

Once you got the bolt in, of course, you weren't allowed to touch it other than to clip in your rope and carry on. Thus you thought long and hard about placing bolts on a tenuous lead. The tradeoff between safety and conserving strength needed to be carefully weighed, often at the expense of safety. Long, sporty leads were generally the norm, resulting in the occasional hundred-foot ripper, often with dire consequences. There was no "If you ain't flying, you ain't trying" mentality. Rather, it was, "If you're flying, you're dying."

As I finished my speech everyone looked at me as though I had just lost my mind (which, of course, I had). Finally Larry Bruce spoke up: "You wanna do what?"

I explained it all again.

"So you mean that I lead a 5.9 pitch with only one piece of protection?"

"Yup, that's the deal," I announced. "Anyone want out?"

They all stood staring at me. Finally someone said, "O.K. Tell you what, nut case: It's your climb, you get to lead the first pitch."

And so I did. I tied into one of our four 165-foot ropes, put three 1-inch by 1/4-inch Rawldrive bolts and two hand drills in my pocket along with a shoelace, a 5-inch sling and a hammer, and started climbing. It got greasy right away, as the Apron tends to be. I smeared and stretched and curled my fingernails onto the thinnest of flakes and depressions. Finally, at around 100 feet off the ground, I plastered myself to the rock, took out a drill, and started pounding.

Somehow I sank a hole almost deep enough to accept the short compression bolt, and pounded that most of the way in before it stopped. No time to ponder the lack of protection as my sewing-machine leg told me to push on. Straight up.

A few minutes later I got the call from below: "You're out of rope!" I stared at the blank rock above me with the climber's mantra of the 1960s and '70s bouncing around in my head: The Leader Must Not Fall. The Leader Must Not Fall.

I yelled down to Greg Davis, who was next on my rope, "I can't stop here. I might be able to belay from a spot about 10 feet higher. Start climbing, and don't fall!" The rope slowly went slack as I moved up another 10 feet to a tiny seam big enough to blot the toes of my climbing shoes, and I started drilling.

Five minutes later I had a 1/2 -inch-deep hole as the sweat poured off my forehead and dripped down the rock, threatening to dislodge my 1970s not-sticky rubber soles. I tied a piece of shoelace around the drill bit, clipped a sling into it, and hung like a dead fish--totally done in, physically and mentally.

I took out the second drill and began drilling a second hole a few inches to one side. Fifteen minutes later I slipped a hanger onto the bolt, welded it into the hole with several extra hammer blows, clipped in, and yelled down with my last scrap of energy, "Off belay!"

The blood slowly stopped pounding in my head as I watched Greg steadily work his way up to me. Straight up. Although there were occasionally larger holds off to the side of our line, Greg played by the rules. He got to my only protection bolt, unclipped the runner, and looked up at me.

"You're fucking insane!" he yelled and kept climbing.

He was 10 feet below my stance when the call came up: "You're out of rope!"

"No shit," he yelled back. "Somebody start climbing! I need 10 more feet!" And he continued.

Now all three of us were supported by two puny belay bolts. Of course these were old-school Rawl-Drive compression bolts that probably wouldn't hold anything more than a falling cat, but that didn't really occur to me at the time. We were climbing straight up! Greg reached me and clipped into the belay.

When there were three of us at the hanging belay I decided it was time to push on. Now it was Greg's turn to lead. Bless his glory-addled brain, he started up as Scott belayed him while I brought up Larry, who had spent the past 10 minutes smeared to the rock 10 feet off the ground while we sorted things out.

The 10-foot dilemma repeated itself when Greg reached the end of his rope without finding anywhere to stop.

"I think there's something about 10 feet higher," he yelled down.

"Right on, brother!" I yelled. "Go for greatness!"

Scott started up, stopping in a particularly nasty spot for 15 minutes while Greg managed to drill a shallow hole at his belay, repeating my shoelace trick before getting in a good bolt.

And so we went up. Scott slithered up the third pitch. As the afternoon sun left the Apron, creating sublime afternoon shade, Larry finished up the fourth and final pitch of the day, a sustained 5.10 slip-fest that had us all whispering to God. But he followed the rules: The route is straight up, and the leader does not fall. We had each led a pitch, and each of us had followed every pitch. We rapped off the two bolts at the top of the fourth pitch, leaving our four ropes in place to continue our quest in the morning.

Also Read: That Time Fred Beckey Shocked Even The Lumberjacks

Back on the ground we had little to say. We had cheated death, and, if you didn't count for the unbelievably dangerous nature of our climbing style, it was fun climbing. As we returned to camp, no one really asked much about our route. It was, after all, just the Apron. How hard could it be? We ate Ramen, drank beers and crashed.

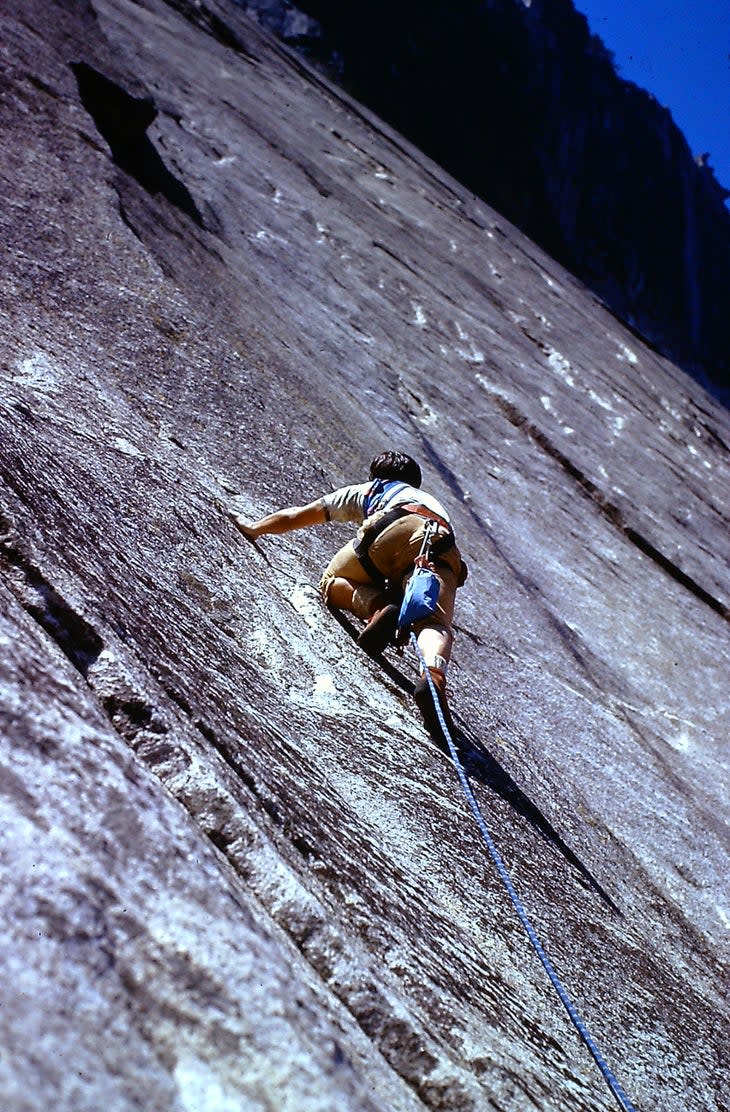

The next day was pretty much a repeat. One by one we jumared back up our fixed ropes to the high point, we hauled them up to the top, and I again led the day's first pitch. I had been a bit worried that I wouldn't have enough adrenaline left in my body but it actually felt good to be climbing again. The rock was perfect, the climbing hard and sustained, and the route finding intricate (even though there was only one direction to go); and since there was absolutely no consideration of falling, the entire scenario became an elegant ballet of the body and mind. Unencumbered by gear--or even the notion of using it--we were free to concentrate on the ascent.

Mentally, this was a much more demanding exercise than soloing: Each of us had three other lives in our hands. In essence, we were all basically soloing at the same time. The leader must not fall. And he hadn't, so far. "Go for greatness!" became the cry each time the leader contemplated putting in a protection bolt less than 100 feet off the belay.

By day three we were all starting to feel a bit tired from the stress but we were only half finished, and there was more no-falling to do. At the top of the eighth pitch, as I started my lead, I looked around and realized both the beauty and absurdity of our situation. At the end of the valley stood Half Dome, icon of climbing, lording over the Apron like a granite idol. I mentally bowed down to its beauty. At the other end stood El Capitan, even more a symbol of overcoming seemingly insurmountable difficulties.

I led my pitch in a blur. The climbing remained engaging, with short, steep blank sections intersected by the occasional half-inch-wide foothold or shallow crack. I ran out my lead from the belay almost 130 feet before putting in my solo protection bolt. Now I'd only fall 45 feet if my shoelace broke at the belay. Luckily I had really good shoelaces.

By the end of the day we could smell the trees and grass and damp earth at the Oasis, the strange but utterly luxurious ledge system two-thirds of the way up to Glacier Point. The Oasis is littered with junk that has been thrown 800 feet from the top of the cliff by tourists who drive up and feel the need to toss something into space. There is a famous photo of Warren "Batso" Harding sitting here in a discarded lawn chair, sporting a straw hat, with a coffee mug and a rake behind him during one of his crazy ascents up the unclimbed and unappealing wall behind him.

It took us a couple hours to jumar the 1,600 feet to the top of our fixed ropes on the last day. I led off into the sky, happy with my climbing, happy with the climb, and happy knowing that by the end of the day I wouldn't be risking my friends' lives any more. At least not so much.

By early afternoon we were at the Oasis, romping around gleefully. That was one hell of a route, we all agreed. It was foolhardy but the fact that we had actually completed it without any death-defying tumbles, or even a fall of any kind, made us think that perhaps it wasn't so difficult after all. I mean, it's not like we were StoneMasters. We were just ... Hosers!

Back in Camp 4 we toyed with the idea of naming the route "Going For Greatness" but that would be even more presumptuous than Stoner's Highway. Nope, Hoser's Highway it would be, our commentary on the absurdity of the Camp 4 climbing hierarchy. I toasted my hero, Walter Bonatti, who followed the line of the water. I toasted another hero, Ed Hillary who "'knocked the bastard off"--meaning Everest. I toasted my hero, Warren Harding, who said, "I don't give a rat's ass what anyone thinks about my routes." Then I toasted my pillow.

A few people had heard about our climb and asked me about it.

"Not sure what to say," I replied truthfully. "It seemed pretty hard to us--perhaps 5.10 in places. Pretty sustained. And the runouts are, well … sporty. Go give it a try and see what you think."

And so they did. A couple of days later a guy came up to me and said in an angry tone, "You guys are fucking crazy! There's no fucking protection. The fucking belays are 175 feet apart! You almost got me killed."

Inside I was bubbling with joy. Outside I was stoic. "So, you liked it?"

"Liked it? Liked it? I got to the 'top' of the first pitch and my belayer had to untie so I could reach the bolts. Then I dragged up our second rope to rappel down and had to jump the last 10 feet just to get back to the ground!"

"So, you didn't finish it?" I asked.

"Finish it? Finish it? No one is ever going to finish it. That's not a route, it's a death wish!" He stomped off.

A couple others gave similarly glowing reports over the next few days, with no one getting higher than the first pitch. I heard that a couple of StoneMasters tried it but those were only unconfirmed rumors.

A couple of years later I saw a report on the first ascent of Hosiers (sic) Highway, giving credit to one member of our group and three people who had never been near it. WTF? I knew those other people--one was Larry's girlfriend, a strong climber, but she had not been on the route with us; one hadn't even been to Yosemite that year; and another was a guy who had scoffed at our plans. Now they were on the first ascent? Then I saw the route written up again in a guidebook as Hoosier's Highway. Hoosier? Hoosier? As in Iowa? I mean, Indiana. More WTF.

Years later when I ran into someone who had actually climbed it, I was elated.

"So, I heard you climbed Hoser's Highway," I said. "What did you think of the runouts?"

"Uh, not too bad," was his answer.

"Really? You didn't think they were a bit ... long?"

"Not really," he replied. "There was one that was around 40 feet, but nothing too wild."

"Forty? As in four-zero? Not like one hundred and forty?"

"No, there are at least five or six bolts on every pitch. Nothing too extreme. You should try it. Pretty hard but fun climbing."

At first it made me mad. Not only was it now a "Hoosier" route, it was littered with bolts. Littered! For the first time in my life I had a small inkling of how Messner and Robbins must have felt when people massacred their routes. How dare anyone add bolts!

Then again, I'm just a Hoser.

After several seasons in Yosemite, Eric Sanford started a climbing school, guide service and heli-ski company in the North Cascades. He has climbed in Alaska, the Alps, the Himalaya, and the Andes, and still thinks the leader must not fall.

This article first appeared in Rock and Ice No. 258.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.